Revising Drafts

Rewriting is the essence of writing well—where the game is won or lost. —William Zinsser

What this handout is about

This handout will motivate you to revise your drafts and give you strategies to revise effectively.

What does it mean to revise?

Revision literally means to “see again,” to look at something from a fresh, critical perspective. It is an ongoing process of rethinking the paper: reconsidering your arguments, reviewing your evidence, refining your purpose, reorganizing your presentation, reviving stale prose.

But I thought revision was just fixing the commas and spelling

Nope. That’s called proofreading. It’s an important step before turning your paper in, but if your ideas are predictable, your thesis is weak, and your organization is a mess, then proofreading will just be putting a band-aid on a bullet wound. When you finish revising, that’s the time to proofread. For more information on the subject, see our handout on proofreading .

How about if I just reword things: look for better words, avoid repetition, etc.? Is that revision?

Well, that’s a part of revision called editing. It’s another important final step in polishing your work. But if you haven’t thought through your ideas, then rephrasing them won’t make any difference.

Why is revision important?

Writing is a process of discovery, and you don’t always produce your best stuff when you first get started. So revision is a chance for you to look critically at what you have written to see:

- if it’s really worth saying,

- if it says what you wanted to say, and

- if a reader will understand what you’re saying.

The process

What steps should i use when i begin to revise.

Here are several things to do. But don’t try them all at one time. Instead, focus on two or three main areas during each revision session:

- Wait awhile after you’ve finished a draft before looking at it again. The Roman poet Horace thought one should wait nine years, but that’s a bit much. A day—a few hours even—will work. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself, and don’t be lazy. Ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

- As The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers puts it, “THINK BIG, don’t tinker” (61). At this stage, you should be concerned with the large issues in the paper, not the commas.

- Check the focus of the paper: Is it appropriate to the assignment? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track through the entire paper?

- Think honestly about your thesis: Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point, or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed altogether? For more information visit our handout on thesis statements .

- Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction state clearly what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

What are some other steps I should consider in later stages of the revision process?

- Examine the balance within your paper: Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of detail early on and then let your points get thinner by the end?

- Check that you have kept your promises to your readers: Does your paper follow through on what the thesis promises? Do you support all the claims in your thesis? Are the tone and formality of the language appropriate for your audience?

- Check the organization: Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Do the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper work better if you moved some things around? For more information visit our handout on reorganizing drafts.

- Check your information: Are all your facts accurate? Are any of your statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

- Check your conclusion: Does the last paragraph tie the paper together smoothly and end on a stimulating note, or does the paper just die a slow, redundant, lame, or abrupt death?

Whoa! I thought I could just revise in a few minutes

Sorry. You may want to start working on your next paper early so that you have plenty of time for revising. That way you can give yourself some time to come back to look at what you’ve written with a fresh pair of eyes. It’s amazing how something that sounded brilliant the moment you wrote it can prove to be less-than-brilliant when you give it a chance to incubate.

But I don’t want to rewrite my whole paper!

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

But I work so hard on what I write that I can’t afford to throw any of it away

If you want to be a polished writer, then you will eventually find out that you can’t afford NOT to throw stuff away. As writers, we often produce lots of material that needs to be tossed. The idea or metaphor or paragraph that I think is most wonderful and brilliant is often the very thing that confuses my reader or ruins the tone of my piece or interrupts the flow of my argument.Writers must be willing to sacrifice their favorite bits of writing for the good of the piece as a whole. In order to trim things down, though, you first have to have plenty of material on the page. One trick is not to hinder yourself while you are composing the first draft because the more you produce, the more you will have to work with when cutting time comes.

But sometimes I revise as I go

That’s OK. Since writing is a circular process, you don’t do everything in some specific order. Sometimes you write something and then tinker with it before moving on. But be warned: there are two potential problems with revising as you go. One is that if you revise only as you go along, you never get to think of the big picture. The key is still to give yourself enough time to look at the essay as a whole once you’ve finished. Another danger to revising as you go is that you may short-circuit your creativity. If you spend too much time tinkering with what is on the page, you may lose some of what hasn’t yet made it to the page. Here’s a tip: Don’t proofread as you go. You may waste time correcting the commas in a sentence that may end up being cut anyway.

How do I go about the process of revising? Any tips?

- Work from a printed copy; it’s easier on the eyes. Also, problems that seem invisible on the screen somehow tend to show up better on paper.

- Another tip is to read the paper out loud. That’s one way to see how well things flow.

- Remember all those questions listed above? Don’t try to tackle all of them in one draft. Pick a few “agendas” for each draft so that you won’t go mad trying to see, all at once, if you’ve done everything.

- Ask lots of questions and don’t flinch from answering them truthfully. For example, ask if there are opposing viewpoints that you haven’t considered yet.

Whenever I revise, I just make things worse. I do my best work without revising

That’s a common misconception that sometimes arises from fear, sometimes from laziness. The truth is, though, that except for those rare moments of inspiration or genius when the perfect ideas expressed in the perfect words in the perfect order flow gracefully and effortlessly from the mind, all experienced writers revise their work. I wrote six drafts of this handout. Hemingway rewrote the last page of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times. If you’re still not convinced, re-read some of your old papers. How do they sound now? What would you revise if you had a chance?

What can get in the way of good revision strategies?

Don’t fall in love with what you have written. If you do, you will be hesitant to change it even if you know it’s not great. Start out with a working thesis, and don’t act like you’re married to it. Instead, act like you’re dating it, seeing if you’re compatible, finding out what it’s like from day to day. If a better thesis comes along, let go of the old one. Also, don’t think of revision as just rewording. It is a chance to look at the entire paper, not just isolated words and sentences.

What happens if I find that I no longer agree with my own point?

If you take revision seriously, sometimes the process will lead you to questions you cannot answer, objections or exceptions to your thesis, cases that don’t fit, loose ends or contradictions that just won’t go away. If this happens (and it will if you think long enough), then you have several choices. You could choose to ignore the loose ends and hope your reader doesn’t notice them, but that’s risky. You could change your thesis completely to fit your new understanding of the issue, or you could adjust your thesis slightly to accommodate the new ideas. Or you could simply acknowledge the contradictions and show why your main point still holds up in spite of them. Most readers know there are no easy answers, so they may be annoyed if you give them a thesis and try to claim that it is always true with no exceptions no matter what.

How do I get really good at revising?

The same way you get really good at golf, piano, or a video game—do it often. Take revision seriously, be disciplined, and set high standards for yourself. Here are three more tips:

- The more you produce, the more you can cut.

- The more you can imagine yourself as a reader looking at this for the first time, the easier it will be to spot potential problems.

- The more you demand of yourself in terms of clarity and elegance, the more clear and elegant your writing will be.

How do I revise at the sentence level?

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and follow Peter Elbow’s advice: “Look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious awkwardness’s that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored—where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression; get back to the energy. Listen even for the tiniest jerk or stumble in your reading, the tiniest lessening of your energy or focus or concentration as you say the words . . . A sentence should be alive” (Writing with Power 135).

Practical advice for ensuring that your sentences are alive:

- Use forceful verbs—replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with “She defends the idea.”

- Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

- Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the following sentence, “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn,” would be much better this way, “Huck Finn repeatedly addresses the issue of integrity.”

- Check your sentence variety. If more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern.

- Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

- Look for sentences that start with “It is” or “There are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

- For more information, please visit our handouts on word choice and style .

How can technology help?

Need some help revising? Take advantage of the revision and versioning features available in modern word processors.

Track your changes. Most word processors and writing tools include a feature that allows you to keep your changes visible until you’re ready to accept them. Using “Track Changes” mode in Word or “Suggesting” mode in Google Docs, for example, allows you to make changes without committing to them.

Compare drafts. Tools that allow you to compare multiple drafts give you the chance to visually track changes over time. Try “File History” or “Compare Documents” modes in Google Doc, Word, and Scrivener to retrieve old drafts, identify changes you’ve made over time, or help you keep a bigger picture in mind as you revise.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Zinsser, William. 2001. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction , 6th ed. New York: Quill.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

An Essay Revision Checklist

Guidelines for Revising a Composition

Maica / Getty Images

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Revision means looking again at what we have written to see how we can improve it. Some of us start revising as soon as we begin a rough draft —restructuring and rearranging sentences as we work out our ideas. Then we return to the draft, perhaps several times, to make further revisions.

Revision as Opportunity

Revising is an opportunity to reconsider our topic, our readers, even our purpose for writing . Taking the time to rethink our approach may encourage us to make major changes in the content and structure of our work.

As a general rule, the best time to revise is not right after you've completed a draft (although at times this is unavoidable). Instead, wait a few hours—even a day or two, if possible—in order to gain some distance from your work. This way you'll be less protective of your writing and better prepared to make changes.

One last bit of advice: read your work aloud when you revise. You may hear problems in your writing that you can't see.

"Never think that what you've written can't be improved. You should always try to make the sentence that much better and make a scene that much clearer. Go over and over the words and reshape them as many times as is needed," (Tracy Chevalier, "Why I Write." The Guardian , 24 Nov. 2006).

Revision Checklist

- Does the essay have a clear and concise main idea? Is this idea made clear to the reader in a thesis statement early in the essay (usually in the introduction )?

- Does the essay have a specific purpose (such as to inform, entertain, evaluate, or persuade)? Have you made this purpose clear to the reader?

- Does the introduction create interest in the topic and make your audience want to read on?

- Is there a clear plan and sense of organization to the essay? Does each paragraph develop logically from the previous one?

- Is each paragraph clearly related to the main idea of the essay? Is there enough information in the essay to support the main idea?

- Is the main point of each paragraph clear? Is each point adequately and clearly defined in a topic sentence and supported with specific details ?

- Are there clear transitions from one paragraph to the next? Have key words and ideas been given proper emphasis in the sentences and paragraphs?

- Are the sentences clear and direct? Can they be understood on the first reading? Are the sentences varied in length and structure? Could any sentences be improved by combining or restructuring them?

- Are the words in the essay clear and precise? Does the essay maintain a consistent tone ?

- Does the essay have an effective conclusion —one that emphasizes the main idea and provides a sense of completeness?

Once you have finished revising your essay, you can turn your attention to the finer details of editing and proofreading your work.

Line Editing Checklist

- Is each sentence clear and complete ?

- Can any short, choppy sentences be improved by combining them?

- Can any long, awkward sentences be improved by breaking them down into shorter units and recombining them?

- Can any wordy sentences be made more concise ?

- Can any run-on sentences be more effectively coordinated or subordinated ?

- Does each verb agree with its subject ?

- Are all verb forms correct and consistent?

- Do pronouns refer clearly to the appropriate nouns ?

- Do all modifying words and phrases refer clearly to the words they are intended to modify?

- Is each word spelled correctly?

- Is the punctuation correct?

- Revision and Editing Checklist for a Narrative Essay

- revision (composition)

- How Do You Edit an Essay?

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- The Difference Between Revising and Editing

- 11 Quick Tips to Improve Your Writing

- Conciseness for Better Composition

- Paragraph Writing

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Self-Evaluation of Essays

- How To Write an Essay

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- Revising a Paper

- Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4 Revising and Editing

Learning objectives.

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising and editing.

- Use peer reviews and editing checklists to assist revising and editing.

- Revise and edit the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

- When you revise , you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

- When you edit , you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

- Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

- Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

- Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

- Use the resources that your college provides. Find out where your school’s writing lab is located and ask about the assistance they provide online and in person.

Many people hear the words critic , critical , and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Creating Unity and Coherence

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity , all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence , the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

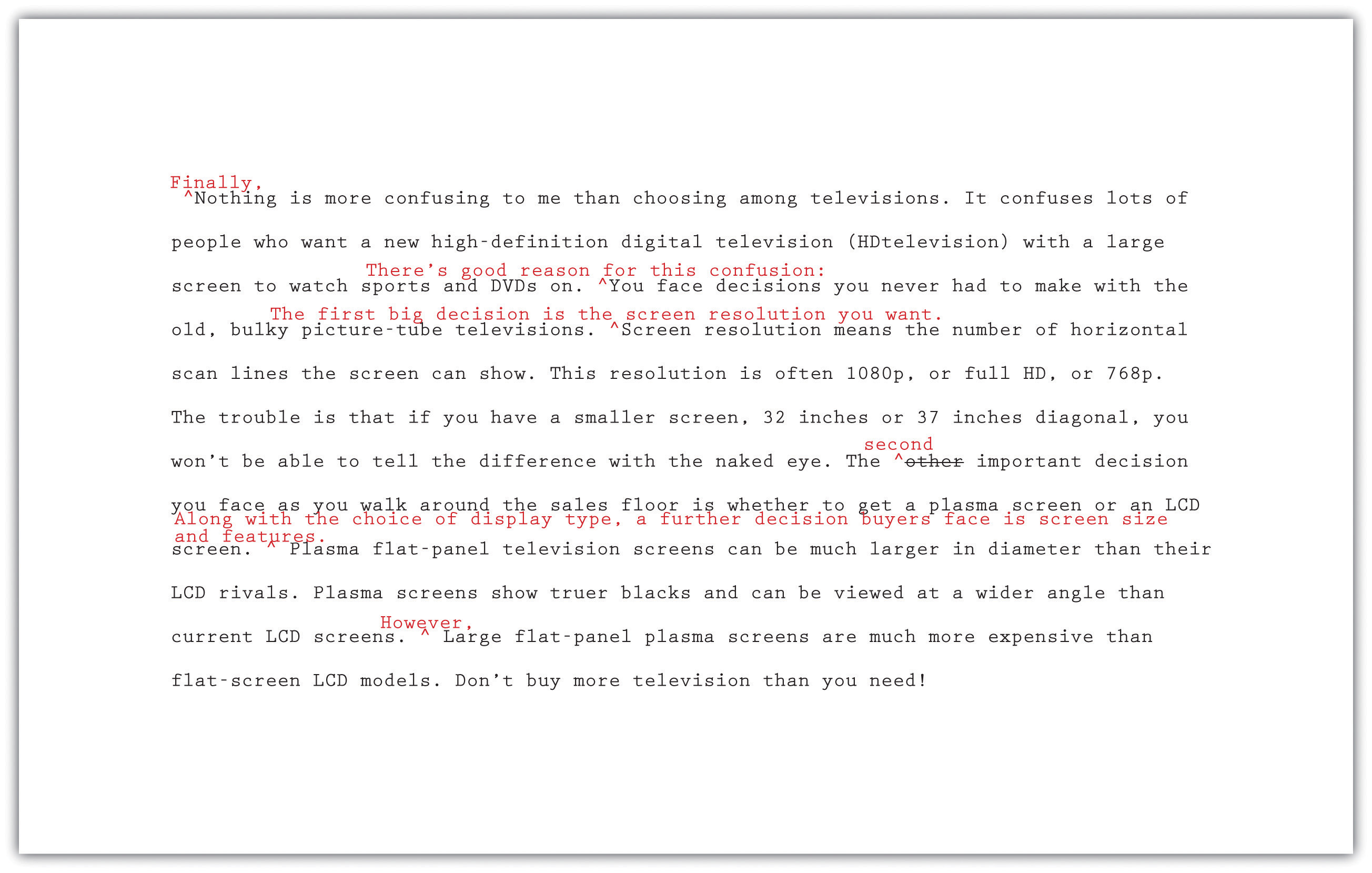

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics store, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches diagonal, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show truer blacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat-panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t let someone make you by more television than you need!

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

- Now start to revise the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” . Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 “Common Transitional Words and Phrases” groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

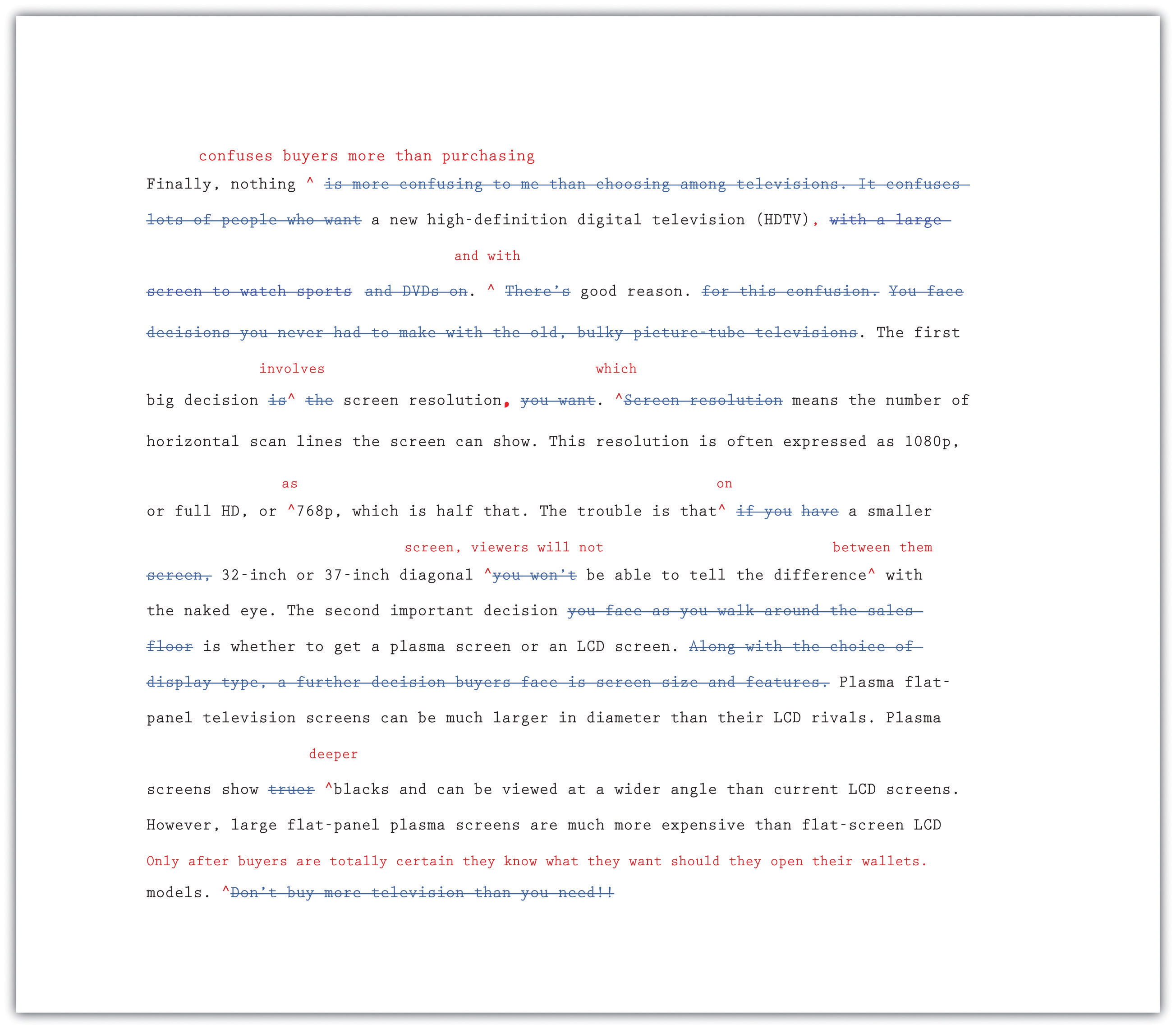

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

2. Now return to the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” and revise it for coherence. Add transition words and phrases where they are needed, and make any other changes that are needed to improve the flow and connection between ideas.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are .

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of , with a mind to , on the subject of , as to whether or not , more or less , as far as…is concerned , and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be . Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be , which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

- Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer , kewl , and rad .

- Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

- Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t , I am in place of I’m , have not in place of haven’t , and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

- Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy , face the music , better late than never , and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

- Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion , complement/compliment , council/counsel , concurrent/consecutive , founder/flounder , and historic/historical . When in doubt, check a dictionary.

- Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited .

- Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing , people , nice , good , bad , interesting , and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

2. Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review .

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

- This essay is about____________________________________________.

- Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

- What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

a. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

b. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

c. Where: ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 “Exercise 4” in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

Editing Your Draft

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah has, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Editing often takes time. Budgeting time into the writing process allows you to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

- Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they do notice misspellings.

- Readers look past your sentences to get to your ideas—unless the sentences are awkward, poorly constructed, and frustrating to read.

- Readers notice when every sentence has the same rhythm as every other sentence, with no variety.

- Readers do not cheer when you use there , their , and they’re correctly, but they notice when you do not.

- Readers will notice the care with which you handled your assignment and your attention to detail in the delivery of an error-free document..

The first section of this book offers a useful review of grammar, mechanics, and usage. Use it to help you eliminate major errors in your writing and refine your understanding of the conventions of language. Do not hesitate to ask for help, too, from peer tutors in your academic department or in the college’s writing lab. In the meantime, use the checklist to help you edit your writing.

Editing Your Writing

- Are some sentences actually sentence fragments?

- Are some sentences run-on sentences? How can I correct them?

- Do some sentences need conjunctions between independent clauses?

- Does every verb agree with its subject?

- Is every verb in the correct tense?

- Are tense forms, especially for irregular verbs, written correctly?

- Have I used subject, object, and possessive personal pronouns correctly?

- Have I used who and whom correctly?

- Is the antecedent of every pronoun clear?

- Do all personal pronouns agree with their antecedents?

- Have I used the correct comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs?

- Is it clear which word a participial phrase modifies, or is it a dangling modifier?

Sentence Structure

- Are all my sentences simple sentences, or do I vary my sentence structure?

- Have I chosen the best coordinating or subordinating conjunctions to join clauses?

- Have I created long, overpacked sentences that should be shortened for clarity?

- Do I see any mistakes in parallel structure?

Punctuation

- Does every sentence end with the correct end punctuation?

- Can I justify the use of every exclamation point?

- Have I used apostrophes correctly to write all singular and plural possessive forms?

- Have I used quotation marks correctly?

Mechanics and Usage

- Can I find any spelling errors? How can I correct them?

- Have I used capital letters where they are needed?

- Have I written abbreviations, where allowed, correctly?

- Can I find any errors in the use of commonly confused words, such as to / too / two ?

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, a classmate, or a peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Remember to use proper format when creating your finished assignment. Sometimes an instructor, a department, or a college will require students to follow specific instructions on titles, margins, page numbers, or the location of the writer’s name. These requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA) style guides, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

With the help of the checklist, edit and proofread your essay.

Key Takeaways

- Revising and editing are the stages of the writing process in which you improve your work before producing a final draft.

- During revising, you add, cut, move, or change information in order to improve content.

- During editing, you take a second look at the words and sentences you used to express your ideas and fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure.

- Unity in writing means that all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong together and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense.

- Coherence in writing means that the writer’s wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and between paragraphs.

- Transitional words and phrases effectively make writing more coherent.

- Writing should be clear and concise, with no unnecessary words.

- Effective formal writing uses specific, appropriate words and avoids slang, contractions, clichés, and overly general words.

- Peer reviews, done properly, can give writers objective feedback about their writing. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate the results of peer reviews and incorporate only useful feedback.

- Remember to budget time for careful editing and proofreading. Use all available resources, including editing checklists, peer editing, and your institution’s writing lab, to improve your editing skills.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Revision practices, hotspotting.

- Glossing for Revision

- Author's Note

- Workshop and Peer Response

Writing Peer Reviews

Strategies for peer review.

This reflective writing activity is predominantly used for revising drafts, but it can be useful in writing and thinking about other texts you read for class—your peers’ and other authors’.

- Choose a draft that you’d like to develop.

- Reread the draft, marking (underline, highlight, star, etc.) places where you think your writing is working. This could be a sentence that expresses a thought-provoking idea, a strong or startling image, a central tension, or a place that could be explored in more detail. These places are the “hot spots” of your draft.

- Copy one of these hot spots onto the top of a clean page; then, put your draft aside. (If you are working on a computer, copy the passage and paste it to a new document). If the passage is long, you can cut it out of the original or fold the draft so only the hot spot shows.

- Now write, using the hot spot as a new first sentence (or paragraph). Write for fifteen to twenty minutes, or as long as you need to develop your ideas. Don’t worry if you “lose” your original idea. You might be in the process of finding a better one.

- Repeat the process as often as feels right. (shoot for 3-4 times)

- Now put your piece back together. You might want to just add the new writing into the piece or substitute it for something you can now delete. You might even take out large sections of the original writing and reorganize the rest around your new writing. Consider how your conception of the “whole” of this draft changes with the new material.

- In your author’s note or writing plan, focus on two things. 1) Write some directions for what you want to do with this writing the next time you work on it. What do you have to change about the text to include the new writing? 2) Reflect upon your revision process. What did you learn about your topic/your text from this process? Did you pursue a tangential idea? Deepen or extend an original idea? Change your perspective on the topic? Realize that you are really interested in another topic altogether?

From UNL Composition Program’s The Writing Teachers’ Sourcebook, 2006

Glossing for Revision Ideas

Read carefully through your draft, glossing each paragraph.

- First determine what the paragraph says. What idea are you trying to get across? In the margins write a paraphrase (the same ideas in different words) for the paragraph. A paraphrase as a part of the glossing activity is a direction-finder, a summary, another way of saying something. What are key words or phrases that help you understand what the paragraph is saying?

- Next, ask yourself how that paragraph functions as a part of your overall piece. What is the paragraph doing? What purpose does it serve? How can you tell?

- Copy your glosses onto another piece of paper. Look at what you’ve got in terms of arrangement or organization. What is happening to the development of ideas? Do your ideas develop in a logical way? Are their other ways to organize your piece that would be more effective? Are there possible directions for this draft to take, places where it isn’t accomplishing what you had hoped? Experiment with rearranging the glosses into different outlines.

- Ask yourself: What difference does it make to the meaning of the text and to potential readers if you arrange ideas differently? How does it change the conceptual framework?

- Write a plan for revision based on what you’ve learned from thinking through various organizational strategies.

Author’s Notes

An Author’s Note gives responders the context they need to have in order to know how to respond to your writing. It should include the following information:

- A statement of the purpose and audience of the text. (E.g.: This is a proposal for a corporate client whom I’m trying to persuade to consider our product.)

- A statement of where the text is in the process of development. (E.g.: first draft, ninth draft, based on an idea I got last night, second half of a draft you’ve already seen.)

- Your own writer’s assessment of the piece. (E.g.: I like this because . . ., I’m worried about this because . . .,I know this part needs work, but I’m not sure, I really like x and want to incorporate more of this idea but don’t know how, etc. . .)

- A sense of the revision strategies you have already tried. (E.g.: I had my roommate read this piece and she suggested these changes. I have tried hotspotting and glossing and they lead to ____. I have tried outlining my paper and I see gaps between my first and second idea but don’t know where to go from here.)

- The kind of response you want, specifically. (E.g.: I am having trouble understanding the process of evolution. Can you point to places where my explanation doesn’t make sense? The first paragraph on page 3 isn’t working for me, what are some strategies I can use to revise? I want to you to look at my overall organization do you understand my main points? I want you to look at my word choice and paragraph structure, specifically on page 1 and 3. etc.)

Author’s Notes are the primary way you, as the writer, establish the kind of response your writing receives. Using Author’s Notes means knowing ahead of time where you are with a piece and what kind of plans you have for it. As you become more accustomed to thinking about your drafts in this way, Author’s Notes become easier to write and more effective reflection and response tools.

Peer Response Groups

All writers get feedback on their writing at some stage in the process. This section offers advice as you give and get feedback in small-group or whole-class formats – or just with a single, trusted reader.

Eventually, you might find that you prefer seeking input at very early stages, when you are still generating ideas. Or, you perhaps you will come to prefer having most of your drafting completed and the text fairly well organized before you look for some feedback. Although we often tend to forget this, it’s also true that we often gain insight into our own writing by reading and responding to others’. It is helpful to think about how a piece of writing is or is not working, whether it’s your own or someone else’s. As you study and assess the way another writer is approaching a project, you might return to your draft with a fresh perspective.

Small Peer Response Groups, Template #2 (For Drafts in Early Stage of Development) We offer here more questions than you could usefully answer in a single peer review session. The idea is that you can pick you and choose–either collectively as a class, or individually as a writer seeking particular kinds of focused response.

- What is the controlling idea of the piece? What makes you think this is the most important idea? How does the writer highlight this idea and build around it?

- Is this idea worth putting “out there”? Why? It is somehow different from what others have been saying? What might it add to the discussion of this subject? What could be the effect(s) of sharing this idea with readers?

- Whom does the piece address? Is this the right readership for this piece? Are these readers best able to address or think about the issues raised? Will they be interested in the piece? Why/why not?

- What other ways are there of thinking about this subject? What has the writer not considered about this subject? What have others been saying about it? How can the writer show that the position in this piece is more appropriate or useful or just plain right than others?

- Does the form seem appropriate for the intended readers, and this idea/purpose? Why or why not? Comment on the expectations readers are likely to bring to this piece because of its form (Example: Readers of pamphlets will expect a readable design and quick, concise chunks of information...)

- How do the different parts of the piece affect you, especially as you imagine yourself as one of the intended readers for the piece? (“As I read the third paragraph, I am frustrated/relieved/ interested/confused...”)

- What would you (again, imagining yourself as an intended reader) like to hear more about? What could you stand hearing less about? Why? Which ideas could be extended or recast? How?

- What assumptions does the text make? Are they fair? Accurate? Do they need to be supported? If so, how? If not, what makes you think that readers will be inclined to accept them?

- Are all of the ideas relevant to one another and to the controlling idea? Is it clear that all of the ideas belong in the same piece? Give an example of how two ideas are either connected or disconnected in the piece.

- Are the sources well chosen for this readership/purpose/message? Are they authoritative but accessible? Does the writer’s use of sources suggest that she/he is knowledgeable about the subject and has something important to add to the discussion? Have you read or heard anything that you think the writer might want to consider?

- What kind of “moves” does the text make (addressing counterarguments, using examples, citing statistics or authorities, etc.)? What kind of appeals (emotional, logical, ethical) are being made here? Are they appropriate to the readers? Which seem most effective? Which least?

Small Peer Response Groups, Template #3 (For Drafts in Later Stage of Development)

- Is the audience clearly indicated in the piece? How? How are readers drawn in and kept reading? Is the form right for these readers? Why/why not?

- Are the purpose and the message (controlling idea) clear in the piece? Do they speak to that audience? Is it clear what the writer wants to audience to do/think/believe after reading this piece?

- What is distinctive about this piece? Does it show creativity? Does it add to the existing conversation about this topic? Explain or give an example.

- Are the “moves” and appeals made in the text appropriate to the audience? How so/not? Are the intended readers likely to find the idea/argument/story compelling/persuasive? Why/why not?

- Is the piece focused? Are there places where the cohesiveness of the piece breaks down, where the focus is lost? Give examples of where ideas are connected or disconnected in the piece.

- Is the piece well organized? Show how/not. Point to specific parts of the text where, for intance, the order of paragraphs works well or doesn’t -- or where sentences build nicely on each other or don’t.

- Is the language appropriate to the audience? Give two examples, either way. Are there grammatical/mechanical problems that need to be addressed? Do you know how to fix them? If not, can you at least point them out? Is the piece well proofread? Are there obvious spelling or typing errors?

Adapted from Chris Gallagher and Amy Lee’s Claiming Writing: Teaching in an Age of Testing (forthcoming, Scholastic Publishers)

Some General Guidelines for Providing Effective Response:

- Respond directly to the writer’s note; be the kind of reader the writer needs.

- Offer honest feedback that is true to your experience of the text, but which respects the writer’s control of the project. Don’t be afraid to say what you really think, but always frame your response in respectful ways. There is a difference between respectfully aggressive readings (which are supportive and generative) and disrespectfully mean-spirited readings (which are discouraging and deadening).

- Be mindful of where the piece is in its development. For instance, don’t closely edit a piece that’s early in the drafting process.

- Give the writer a sense of what you think the piece says, and how you think it works.

- Give the writer a sense of how you experience the piece.

- Ask the writer probing but supportive questions about the text and its subject; aim to keep the writer thinking hard about the nature of her/his task.

- Help the writer imagine potential audiences/purposes for the piece. If the writer knows the audience and purpose for the piece, try to read it with those in mind.

- Aim for both “global” responses that speak to the whole piece and more “local” responses that point to specific places in the text.

- Help the writer see her/his piece from other perspectives.

- Offer the writer a response s/he can handle; don’t overwhelm the writer, but be substantive in your response.

- Offer the writer concrete suggestions for revision – send her or him back to specific places in the text to do some work.

- Above all, aim to send the writer away from the response session excited about her/his project, and confident that s/he knows where to take it next.

Things we want to hear:

- Summarizing/Saying Back—Here is what I see this saying…

- Glossing—Here is a word or phrase that condenses this paragraph or section…

- Responding—As I read this paragraph, I…

- Pointing—What seems most important here is... What seems to be missing here is…

- Extending—You could also apply this to… What would happen if you...

- Encouraging—This section works well for me because…

- Suggesting—If I were you, I would add… You could move that paragraph…

- Soliciting—Could you say more here about...

- Connecting—In my experience, this… That’s like what x says… I saw some research on this…

- Evaluating—This opening is focused, well-developed, catchy…

- Counterarguing—Another way to look at this is…

- Questioning—Why do you say…

Things We Want to Hear Only on Mostly “Finished” Pieces:

- Editing—you need a comma here …

Things We Don’t Want to Hear:

- “I like it.”

- “I hate it.”

- “I wouldn’t change a thing.”

- “How can you actually believe that crap?”

- “This has nothing to do with the paper, but this reminds me of when I . . .”

Since these verbs have different connotations depending on the context in which they are used, you will want to be sure to re-read your sentence and choose the verb that is most appropriate for your intended purpose.

Sentence Patterns

In drafting, we focus so much on getting an idea down on paper or recreating a memory on paper that we often don’t pay attention to how our sentences work or how they are constructed. That’s just fine (good even!) in drafting. In the revising/editing process, however, we shift from considering the theme or argument of our text to analyzing the way our sentences are composed.

Go through a couple paragraphs of your draft and figure out how your sentences are put together by finding the subject and verb of each sentence. Many times we start sentences with the same word over and over (like “I” or “You” or “He/She”) and the verb immediately follows. Once you figure out what your particular patterns are (and this may take awhile—first to find the subjects and verbs and then to see the pattern), then try varying your sentence patterns.

For example, short, quick sentences might be good in an essay that has a fast-paced or suspenseful feel. Long, intricate sentences may be just right for an in-depth reflection. If each sentence has the same subject/verb structure, it might not be clear which sentence carries the most meaning in the paragraph or which ideas are subordinate to or embedded within an idea. Try adding introductory phrases or connecting two sentences. Try varying the sentence style in different parts of your essay. Your main goal is to make your paper appealing, interesting, and rhetorically effective at the sentence level.

Reading for Grammar, Mechanics, and Punctuation Issues

One way to make sure you catch most of the comma issues in your paper is to look at every comma you use. Read your essay just for commas. Every time you see one, stop and make sure you’ve used it specifically and in accordance with the punctuation rules you’re following. This is time-consuming, but it also works.

You can do this for any punctuation and even for point of view and tense. Read for semicolons or apostrophes or colons. Read looking for “you” (if your paper is supposed to be in first person “I”) and change the “you” to first person. Read and stop on every verb to see if they are all in the tense you have chosen for your paper. When doing this kind of editing/revising work, you can do several readings of your essay with a different reading purpose each time.

- Twin Cities

- Campus Today

- Directories

University of Minnesota Crookston

- Mission, Vision & Values

- Campus Directory

- Campus Maps/Directions

- Transportation and Lodging

- Crookston Community

- Chancellor's Office

- Quick Facts

- Tuition & Costs

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Organizational Chart

- Accreditation

- Strategic Planning

- Awards and Recognition

- Policies & Procedures

- Campus Reporting

- Public Safety

- Admissions Home

- First Year Student

- Transfer Student

- Online Student

- International Student

- Military Veteran Student

- PSEO Student

- More Student Types...

- Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Request Info

- Visit Campus

- Admitted Students

- Majors, Minors & Programs

- Agriculture and Natural Resources

- Humanities, Social Sciences, and Education

- Math, Science and Technology

- Teacher Education Unit

- Class Schedules & Registration

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Organizations

- Events Calendar

- Student Activities

- Outdoor Equipment Rental

- Intramural & Club Sports

- Wellness Center

- Golden Eagle Athletics

- Health Services

- Career Services

- Counseling Services

- Success Center/Tutoring

- Computer Help Desk

- Scholarships & Aid

- Eagle's Essentials Pantry

- Transportation

- Dining Options

- Residential Life

- Safety & Security

- Crookston & NW Minnesota

- Important Dates & Deadlines

- Cross Country

- Equestrian - Jumping Seat

- Equestrian - Western

- Teambackers

- Campus News

- Student Dates & Deadlines

- Social Media

- Publications & Archives

- Summer Camps

- Alumni/Donor Awards

- Alumni and Donor Relations

Writing Center

How to revise drafts, now the real work begins....

After writing the first draft of an essay, you may think much of your work is done, but actually the real work – revising – is just beginning. The good news is that by this point in the writing process you have gained some perspective and can ask yourself some questions: Did I develop my subject matter appropriately? Did my thesis change or evolve during writing? Did I communicate my ideas effectively and clearly? Would I like to revise, but feel uncertain about how to do it?

Also see the UMN Crookston Writing Center's Revising and Editing Handout .

How to Revise

First, put your draft aside for a little while. Time away from your essay will allow for more objective self-evaluation. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself; ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

Check the focus of the paper. Is it appropriate to the assignment prompt? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track throughout the entire paper? (At this stage, you should be concerned with the large, content-related issues in the paper, not the grammar and sentence structure).

Get feedback . Since you already know what you’re trying to say, you aren’t always the best judge of where your draft is clear or unclear. Let another reader tell you. Then discuss aloud what you were trying to achieve. In articulating for someone else what you meant to argue, you will clarify ideas for yourself.

Think honestly about your thesis. Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point? Or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed completely?

Examine the balance within your paper. Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of details early on and then let your points get thinner by the end? Based on what you did in the previous step, restructure your argument: reorder your points and cut anything that’s irrelevant or redundant. You may want to return to your sources for additional supporting evidence.

Now that you know what you’re really arguing, work on your introduction and conclusion . Make sure to begin your paragraphs with topic sentences, linking the idea(s) in each paragraph to those proposed in the thesis.

Proofread. Aim for precision and economy in language. Read aloud so you can hear imperfections. (Your ear may pick up what your eye has missed). Note that this step comes LAST. There’s no point in making a sentence grammatically perfect if it’s going to be changed or deleted anyway.

As you revise your own work, keep the following in mind:

Revision means rethinking your thesis. It is unreasonable to expect to come up with the best thesis possible – one that accounts for all aspects of your topic – before beginning a draft, or even during a first draft. The best theses evolve; they are actually produced during the writing process. Successful revision involves bringing your thesis into focus—or changing it altogether.

Revision means making structural changes. Drafting is usually a process of discovering an idea or argument. Your argument will not become clearer if you only tinker with individual sentences. Successful revision involves bringing the strongest ideas to the front of the essay, reordering the main points, and cutting irrelevant sections. It also involves making the argument’s structure visible by strengthening topic sentences and transitions.

Revision takes time. Avoid shortcuts: the reward for sustained effort is an essay that is clearer, more persuasive, and more sophisticated.

Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction clearly state what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

Check the organization. Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Doe the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper be work better if you moved some things around?

Check your information. Are all your facts accurate? Are any of our statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

Revising Sentences

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious places that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored – where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression: get back to the energy.

Tips for writing good sentences:

Use forceful verbs – replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with ‘she defends the idea.” Also, try to stay in the active voice.

Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the sentence “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn ” would be much better this way: “ Huck Finn repeated addresses the issue of integrity.”

Check your sentence variety. IF more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern. Also, try to mix simple sentences with compound and compound-complex sentences for variety.

Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

Look for sentences that start with “it is” or “there are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

By Jocelyn Rolling, English Instructor Last edited October 2016 by Allison Haas, M.A.

Writing Studio

What is revision.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Revision handout PDF Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Revision is not merely proofreading or editing an essay. Proofreading involves making minor changes, such as putting a comma here, changing a word there, deleting part of a sentence, and so on. Revision, on the other hand, involves making more substantial changes.

Literally, it means re-seeing what you have written in order to re-examine (and possibly change and develop) what you have said or how you have said it. One might revise the argument, organization, style, or tone of one’s paper.

Below you’ll find some helpful activities to help you begin to think through and plan out revisions.

Revision Strategies

Memory draft.

Set aside what you’ve written and rewrite your essay from memory. Compare the draft of your paper to your memory draft. Does your original draft clearly reflect what you want to argue? Do you need to modify the thesis? Should you reorganize parts of your paper?

This technique helps point out what you think you are doing in comparison to what you are actually doing in a piece of writing.

Reverse Outline

Some writers find it helpful to make an outline before writing. A reverse outline, which one makes after writing a draft, can help you determine whether your paper should be reorganized. To make a reverse outline and use it to revise your paper: Read through your paper, making notes in the margins about the main point of each paragraph.

Create your reverse outline by writing those notes down on a separate piece of paper. Use your outline to do three things:

- See whether each paragraph plays a role in supporting your thesis.

- Look for unnecessary repetition of ideas.

- Compare your reverse outline with your draft to see whether the sentences in each paragraph are related to the main point of that paragraph, per the reverse outline. This technique is helpful in reconsidering the organization and coherence of an essay. By figuring out what each paragraph contributes to your paper, you will be able to see where each fits best within it.

Anatomy of a Paragraph

Select different colored highlighters to represent the different elements that should be found in an argumentative essay. Make a key somewhere on the first page, noting what each color represents. You might consider attributing a color to thesis, argumentative topic sentence, evidence, analysis, and fluffy flimflam. Now, color code your essay. When you’re finished, diagnose what you see, paying attention to where you’ve placed your topic sentences, whether you’re using enough evidence, and whether you could expand or streamline your analysis.

This strategy is helpful for visual learners and authors who feel overwhelmed by the length of their draft or scope of their revision project. It also helps to illustrate the organization and development of an argument.

Unpacking an Idea

Select a certain paragraph in your essay and try to explain in more detail how the concepts or ideas fit together. Unpack the evidence for your claims by showing how it supports your topic sentence, main idea, or thesis.

This technique will help you more deliberately explain the steps in your reasoning and point out where any gaps may have occurred within it. It will help you establish how these reasons, in turn, lead to your conclusions.

Exploding a Moment

Select a certain paragraph or section from your essay and write new essays or paragraphs from that section. Through this technique, you might discover new ideas—or new connections between ideas—that you’ll want to emphasize in your paper or in a new paper in the future.

3×5 Note Card

Describe each paragraph of your draft on a separate note card. On one side of the note card, write the topic sentence; on the other, list the evidence you use to back up your topic sentence. Next, evaluate how each paragraph fits into your thesis statement.

This technique will help you look at a draft on the paragraph-level.

Writing Between the Lines

Add information between sentences and paragraphs to clarify concepts and ideas that need further explanation.

This technique helps the writer to be aware of complex concepts and to determine what needs additional explanation.

This technique helps you look at your subject from six different points of view (imagine the 6 sides of a cube and you get the idea).

Take the topic of your paper (or your thesis) and proceed through the following six steps:

- Describe it.

- Compare it.

- Associate it with something else you know.

- Analyze it (meaning break it into parts).

- Apply it to a situation with which you are familiar.

- Argue for or against it.

Write a paragraph, page, or more about each of the six points of view on your subject.

Talk Your Paper

Tell a friend what your paper is about. Pay attention to your explanation. Are all of the ideas you describe actually in the paper? Where did you start in explaining your ideas? Does your paper match your description? Can the listener easily find all of the ideas you mention in your description?

This technique helps match up verbal explanations to written explanations. Which presents your ideas most clearly, accurately, and effectively?

Ask Someone to Read Your Paper Out Loud for You

Ask a friend to read your draft out loud to you. What do you hear? Where does your reader stumble, sound confused, or have questions? Did your reader ever get lost in your text? Did your ideas flow in a logical order and progress from paragraph to paragraph? Did the reader need more information at any point?

This technique helps a writer gain perspective on an essay by hearing first-hand the reaction of a fellow student to it.

Ask Someone without Knowledge of the Course to Read Your Paper

You can tell if your draft works by sharing it with someone unfamiliar with the context. If she can follow your ideas, your professor will be able to as well.

This technique will help you test out the clarity of your paper on those not acquainted with the course material.

Return to the Prompt

This technique may seem obvious, but once you’ve gotten going on an assignment, you may get carried away from what the instructions have asked you to do. Double check the prompt. Have you answered all of the questions (or parts of questions) thoroughly? Is there any part you may have neglected or missed?

This technique will help you keep in mind what the questions are asking and to determine whether you have addressed all of their components effectively.

Last revised: 08/2016 | Adapted for web delivery: 03/2021

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, working through revision: rethink, revise, reflect.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Megan McIntyre - University of Arkansas

Revision is what happens after you’ve written something; this might mean you have a full draft or a paragraph or two. It’s an opportunity for you to revisit your work, rethink your approach, and make changes to your text so that your work better fits the task you were given or your goals for writing in the first place. In what follows, I lay out some definitions for revision and then offer five steps that can help you revise your work in thoughtful but manageable ways. These steps are most helpful when you have a section or the full piece drafted but can also be helpful at most any step of the writing process.