- world affairs

What Cultural Genocide Looks Like for Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

S eptember 2023 saw the tumultuous and traumatic departure of over 100,000 Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh . This mass exodus of an indigenous people from their homeland followed nine months of starvation-by-blockade , which culminated in a murderous military assault on Sept. 19.

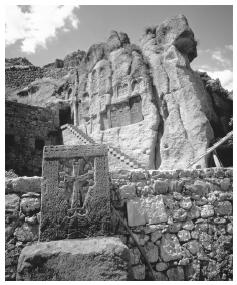

These men, women, and children, terrified for their lives, left behind entire worlds: their schools and shops; their fields, flocks, and vineyards; the cemeteries of their ancestors. They also left behind the churches, large and small, ancient and more modern, magnificent and modest, where they had for centuries gathered together and prayed. They also left behind bridges, fortifications, early modern mansions, and Soviet-era monuments, such as the beloved “We are Our Mountains” statues. What will happen now to those places? There is no question, actually.

We know well what happened in Julfa , in Nakhichevan : a spectacular landscape of 16th-century Armenian tombstones was erased from the face the earth by Azerbaijan over a period of years. We know what happened to the Church of the Mother of God in Jebrayil and the Armenian cemetery in the village of Mets Tagher (or Böyük Taglar) —both were completely scrubbed from the landscape using earthmoving equipment like bulldozers. And we know what happened to the Cathedral of Ghazanchetsots in Shushi, which was, in turn, shelled, vandalized with graffiti, “restored” without its Armenian cupola, and now rebranded as a “Christian” temple. The brazenness of these actions, as journalist Joshua Kucera wrote in May 2021 , “suggests a growing confidence that [Baku] can remake their newly retaken territories in whatever image they want.”

The annihilation of millennia of Armenian life in Arstakh was enabled by the inaction and seeming indifference of those who might have prevented it. The United States and the European Union speak loftily of universal human rights, but did nothing for nine months while the people of Arstakh were denied food, medicine, fuel, and other vital supplies. They did nothing to enforce the order of the International Court of Justice demanding back in February 2023 that Azerbaijan end its blockade. That inaction clearly emboldened Azerbaijan to attack—just as it will encourage others to do the same elsewhere.

More From TIME

Read More: The U.S. Keeps Failing Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

It’s important to understand the stakes of this kind of cultural erasure: These monuments and stones testify to the generations of Armenians who worshipped in and cared about them. To destroy them, is to erase not only a culture, but a people. As art historian Barry Flood observed in 2016 about the destruction of cultural heritage by the so-called Islamic state since 2014, “the physical destruction of communal connective tissues—the archives, artifacts, and monuments in which complex micro-histories were instantiated—means that there are now things about these pasts that cannot and never will be known.” The Julfa cemetery is a tragic example of such loss.

If history is any indication, ethnic cleansing tends to be followed by all kinds of cultural destruction, from vandalism to complete effacement from the landscape. The latter tactic will be used with smaller, lesser-known churches. It will be a sinister way to remove less famous Armenian monuments, which will serve the narrative that there were no Armenians there in the early modern period to begin with.

Falsification will also occur, in which Armenian monuments are provided with newly created histories and contexts. The 13 th - century monasteries of Dadivank (in the Kalbajar district) and Gandzasar (in the Martakert province), both magnificent and characteristic examples of medieval Armenian architecture, have already been rebranded as “ancient Caucasian Albanian temples.” Expect these and other sites to become venues for conferences and workshops to highlight “ancient Caucasian Albanian culture.” As for the countless Armenian inscriptions on these buildings, khachkars, and tombstones: these, as President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev announced in February 2021, are Armenian forgeries , and will be “restored” to their “original appearance” (presumably through gouging, sandblasting, or removing of Armenian inscribed stones, as was done in the 1980s).

Finally, there will be a celebration of the “multiculturalism” of Azerbaijan. “Come to Karabakh, home of ancient Christians,” people will say. “Please ignore the gouged-out letters on that stone wall, for it is not an Armenian inscription. There were never Armenians here!" Except for soldiers and invaders, like the ones depicted in a reprehensible museum in Baku, featuring waxen figures of dead Armenian soldiers —a sight so dehumanizing that an international human rights organizations, including Azerbaijani activists, cried out for its closure.

This is how cultural genocide plays out. A little more than 100 years ago was the Armenian Genocide waged by the Ottoman Empire, followed by largescale looting, vandalization, and destruction of Armenian sites across what is now modern-day Turkey. The prospect of a second cultural genocide is now on the table. Except now, Armenians will watch the spectacle unfold online, enduring the trauma site by site and monument by monument.

In 2020, Armenian activists called for international monitoring of vulnerable sites in Nagorno-Karabakh by UNESCO and other heritage organizations. Nothing happened. Now is the time for the world to protect what Armenian culture remains in Nagorno-Karabakh. If we don’t, what culture will be next to go?

Want more fresh perspectives? Sign up for TIME POV , our opinion newsletter .

The original version of this story misstated the president of Azerbaijan's name. It is Ilham Aliyev, not Ilhan Aliyev.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Melinda French Gates Is Going It Alone

- What to Do if You Can’t Afford Your Medications

- How to Buy Groceries Without Breaking the Bank

- Sienna Miller Is the Reason to Watch Horizon

- Why So Many Bitcoin Mining Companies Are Pivoting to AI

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Armenian Language Program

Armenian (հայերեն) is the official language in the Republic of Armenia as well as the Republic of Artsakh. The Armenian language belongs to the Indo-European language family constituting its own Armenian branch. Historically having been used only within the Armenian Highlands, Armenian is currently spoken worldwide throughout the Armenian diaspora. Armenian has its own writing system, the Armenian alphabet.

Literature written in Armenian appeared in the 5th century right after the Armenian alphabet was created by Saint Mesrop Mashtots in 405 AD. The written language of the time, called Classical Armenian or Grabar (գրաբար), remained the Armenian literary language, with various changes, until the beginning of the 19th c. It contained numerous borrowings from Middle Iranian languages (primarily Parthian), Greek, Syriac, Arabic, Mongol, and Persian. The early grammatical forms had much in common with classical Greek and Latin. Many ancient manuscripts originally written in Ancient Greek, Persian, Hebrew, Syriac and Latin survive only in Classical Armenian translation.

Spoken Armenian, on the other hand, developed independently of the written language. Many dialects appeared when Armenian communities became separated by geography or politics. In the 19th c., the traditional Armenian homeland was divided into Eastern Armenia (conquered by the Russian Empire) and Western Armenia (remaining under Ottoman control). The intellectual and cultural life of the Armenian communities were consolidated in two separate centers, one in Tbilisi and the other in Istanbul. The new literary forms and styles reached Armenians living in both regions, and created a need to use the vernacular (աշխարհաբար) as the literary language instead of the now outdated Grabar. Two major standards emerged: Eastern and Western Armenian. The proliferation of newspapers and emergence of literary works in both dialects and the development of a network of schools increased the rate of literacy.

By the turn of the 20th c. both standards of the modern Armenian language prevailed over Grabar. After World War I, the newly emerged Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic used Eastern Armenian as its official language whereas the diaspora created after the Armenian Genocide preserved the Western Armenian branch.

Modern Armenian has undergone many transformations in phonology and mostly in grammar, creating a certain degree of difficulty for learners to move from Eastern standard to Western or from the modern language to the Classical. The vocabulary, on the other hand, has survived to present day and is at some extent shared by the two standard branches and the Classical Armenian. The alphabet (with two additional letters) is still used today.

The Armenian Language Program

Started in September of 2001, the Armenian Language Program intended to compliment the annual one-quarter course by a visiting Dumanian Professor in Armenian Studies, and to ensure the continuity of Armenian instruction, with an objective of further promoting and enriching Armenian Studies at the University of Chicago. The program aims at serving students, both graduate and undergraduate, as the source for Armenian language instruction as well as History and Culture. In addition, the program prepares students for research in Armenian and related Area Studies.

The undergraduates mostly take Armenian to better expose themselves to Armenian culture or visit Armenia. Those are mostly heritage learners. Some also become NELC minors. Others, mostly graduate students, take Armenian as their second or third language and focus on translations for their research (in Armenian, Byzantine, or Islamic Studies, Indo-European or General Linguistics, Archaeology, History of Religions, Post-Soviet Studies, Human Rights Studies, etc.). Knowledge of Armenian language (both Modern and Classical) is crucial for their research, they would need Classical Armenian to use the original Armenian historical sources (i.e., related to Zoroastrian religion, translations of and commentaries on Greek philosophical texts, the history of the Byzantine and Armenian Church, historical chronicles, literary works, etc. from 5th to 19th c.), as well as Modern Armenian to be able to read modern Armenian literary works, mass media or scholarly publications in their field.

Since Armenian is considered a less commonly taught language there are on average 2-4 students enrolled in each level which creates a more advantageous circumstance for the Armenian language learners facilitating their more accelerated language acquisition within 1-2 years.

Furthermore, as part of the CLC collaborative language pedagogy, starting in Autumn of 2014 Elementary and Intermediate Armenian are offered as “shared curricula” courses to include students in remote locations who are enrolled at institutions which participate in course-share program.

As for other opportunities, over the years the students enrolled in the Armenian language courses were very successful in applying and obtaining FLAS grants, Critical Language Scholarships (CLS), Fulbright and Boren fellowships, and other summer and year-long language programs to study Armenian in Armenia.

Armenian Language Program Faculty

Hripsime Haroutunian

Courses offered.

The NELC Department currently offers three levels of Modern Armenian instruction and at least one quarter of Classical Armenian per year. The Armenian language courses offered annually or as needed are as follows:

- ARME 10101-02-03 Elementary Modern Armenian This three-quarter sequence focuses on the acquisition of basic speaking, listening, reading and writing skills in modern formal and spoken Armenian. The course utilizes the most advanced computer technology and audio-visual aids enabling students to master the alphabet, a core vocabulary, and some basic grammatical structures in order to communicate their basic survivor’s needs in Armenian, understand simple texts and to achieve a minimal level of proficiency in modern formal and spoken Armenian.

- ARME 20101-02-03 Intermediate Modern Armenian This sequence covers a wider-range vocabulary and more complex grammatical structures in modern formal and colloquial Armenian. Each class includes a healthy balance of real-life like conversations (shopping, ordering food, asking directions, getting around in the city, banking, etc.), readings (dialogues, jokes, stories, news, etc.) and writings (e-mailing, filling forms, essays, etc.). The students can also communicate in Armenian well beyond basic needs about the daily life and obtain some level of fluency in their professional interests.

- ARME 30101 Independent Study : Advanced Armenian The course focuses on the improvement of speaking, listening, reading and writing skills in modern formal and spoken Armenian. The course covers a rich vocabulary in modern formal and colloquial Armenian, and the most complex grammatical structures and frames. The main objective is literary fluency. Reading assignments include a variety of texts (literary works, newspaper articles, etc.). Students practice the vocabulary (newly acquired in their readings) through discussions and critical analysis of texts in Armenian. There are also enhanced writing assignments: essays on given topics, writing blogs or wiki pages, etc. The goal is to achieve an advanced level of proficiency in modern formal and spoken Armenian. The course may be tailored to individual students' reading and research needs.

- ARME 10501 Introduction to Classical Armenian The one-quarter course focuses on the basic grammatical structure and vocabulary of the Classical Armenian language, Grabar (one of the oldest IndoEuropean languages). It enables students to achieve basic reading skills in the Classical Armenian language. Reading assignments include a selection of original Armenian literature, mostly works by 5th c. historians, as well as passages from the Bible, while a considerable amount of historical and cultural issues about Armenia are discussed and illustrated through the text interpretations. It complements the Modern Armenian language instruction and provides more profound and solid knowledge of Armenian language and its ancient dialects, targeted especially to graduate students. Recommended for students with interests in Armenian Studies, Classics, Medieval Studies, Divinity, Indo-European or General Linguistics. It is usually offered as dictated by student needs. Students may take the Classical Armenian course before or even without taking any Modern Armenian.

Advanced students can also register for Reading and Research classes in Armenian to improve their ability to read targeted academic & scholarly materials for their research. Those courses are offered on-demand.

A considerable amount of historical-political and social-cultural issues about Armenia are skillfully built into the language courses. In addition, related courses on various aspects of Armenian art, culture and literature are occasionally offered including the NEHC 20692 Armenian History through Art and Culture (offered annually).

Class Times

In scheduling first-year classes, every effort is made to make sure that interested students are not excluded because of scheduling conflicts. Second- and third-year classes are generally by arrangement, based on the mutual convenience of instructor and students.

Placement and Proficiency Exams

Prospective Armenian students (other than beginners) have to take a placement test before registering for second-year and above classes. A placement test for incoming first-year undergraduates and graduate students is usually administered during orientation week.

Please contact Hripsime Haroutunian ([email protected]) with any questions concerning the time and date of the placement exam.

Additionally, a language competency exam is offered at the end of Spring quarter for those taking this course as college language requirement.

Extracurricular Activities

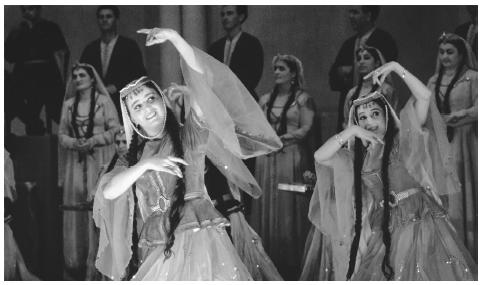

Aside from the formal academic curriculum, there are weekly Armenian Circle meetings (to listen to lectures on Armenian culture and history, to watch Armenian movies and documentaries on Armenia, practice Armenian language while indulging in tasty Armenian cuisine, etc.), as well as “special hands-on classes” in Armenian cuisine, field trips to community events, annual Armenian Cultural Nights (evenings of Armenian poetry recital, music performance and staging of Armenian plays by the students). Students also have opportunities to make their own presentations on Armenian art, culture, current issues or related topics.

What if I have a potential schedule conflict?

Please email the instructor ([email protected]) explaining your problem.

I’d like to audit/sit-in on an Armenian course. Is that possible?

Please consider registering for the class. In rare cases, if you are absolutely unable to enroll in the Autumn quarter but have all intentions to register for the Winter and Spring quarters you may be permitted to audit the Autumn quarter class at the Instructor’s discretion. Note that you must complete all the required assignments for the course (including regular attendance).

I already have some background in spoken or written Armenian. What class should I take?

You will need to take the placement exam, so that the instructor can learn about your levels of spoken and written Armenian.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

Plant and animal life

Ethnic groups.

- Settlement patterns

- Demographic trends

- Agriculture

- Transportation

- Constitutional framework

- Health and welfare

- Cultural life

- The Artaxiads

- The Arsacids

- The marzpān s

- The Mamikonians and Bagratids

- Lesser Armenia

- Ottomans and Ṣafavids

- Armenia and Europe

- The republic of Armenia

- Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

- Armenia at the turn of the century

- Serzh Sargsyan government

- Velvet Revolution

- Nikol Pashinyan government

- How did Pompey the Great earn his nickname?

- Were Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar allies?

- Why did Pompey the Great fight Julius Caesar?

- How did Pompey the Great lose to Julius Caesar?

- How did Pompey the Great die?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- AllPoetry - Sarojini Naidu

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - Armenia

- Official Tourism Site of Armenia

- BBC News - Armenia country profile

- Livius - Armenia

- Armenia - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Armenia - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

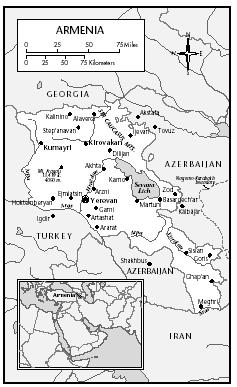

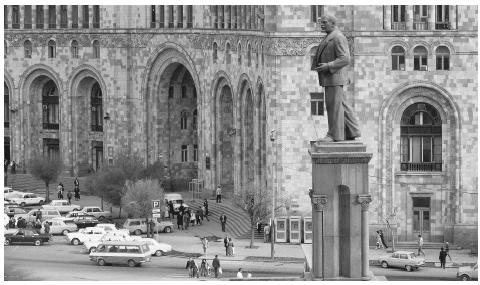

Armenia , landlocked country of Transcaucasia , lying just south of the great mountain range of the Caucasus and fronting the northwestern extremity of Asia . To the north and east Armenia is bounded by Georgia and Azerbaijan , while its neighbours to the southeast and west are, respectively, Iran and Turkey . Naxçıvan , an exclave of Azerbaijan, borders Armenia to the southwest. The capital is Yerevan (Erevan).

Modern Armenia comprises only a small portion of ancient Armenia, one of the world’s oldest centres of civilization. At its height, Armenia extended from the south-central Black Sea coast to the Caspian Sea and from the Mediterranean Sea to Lake Urmia in present-day Iran. Ancient Armenia was subjected to constant foreign incursions, finally losing its autonomy in the 14th century ce . The centuries-long rule of Ottoman and Persian conquerors imperiled the very existence of the Armenian people. Eastern Armenia was annexed by Russia during the 19th century, while western Armenia remained under Ottoman rule, and in 1894–96 and 1915 the Ottoman government perpetrated systematic massacres and forced deportations of Armenians.

Recent News

The portion of Armenia lying within the former Russian Empire declared independence on May 28, 1918, but in 1920 it was invaded by forces from Turkey and Soviet Russia. The Soviet Republic of Armenia was established on November 29, 1920; in 1922 Armenia became part of the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic; and in 1936 this republic was dissolved and Armenia became a constituent (union) republic of the Soviet Union . Armenia declared sovereignty on August 23, 1990, and independence on September 23, 1991.

The status of Nagorno-Karabakh (also called Artsakh), an enclave of 1,700 square miles (4,400 square km) in southwestern Azerbaijan populated primarily by ethnic Armenians, was from 1988 the source of bitter conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. By the mid-1990s Karabakh Armenian forces had occupied much of southwestern Azerbaijan, but, after a devastating war in 2020, they were compelled to withdraw from most of that area.

Armenia is a mountainous country characterized by a great variety of scenery and geologic instability. The average elevation is 5,900 feet (1,800 metres) above sea level . There are no lowlands: half the territory lies at elevations of 3,300 to 6,600 feet; only about one-tenth lies below the 3,300-foot mark.

The northwestern part of the Armenian Highland—containing Mount Aragats (Alaghez), the highest peak (13,418 feet, or 4,090 metres) in the country—is a combination of lofty mountain ranges, deep river valleys, and lava plateaus dotted with extinct volcanoes. To the north and east, the Somkhet, Bazum, Pambak, Gugark, Areguni, Shakhdag, and Vardenis ranges of the Lesser Caucasus lie across the northern sector of Armenia. Elevated volcanic plateaus (Lory, Shirak, and others), cut by deep river valleys, lie amid these ranges.

In the eastern part of Armenia, the Sevan Basin, containing Lake Sevan (525 square miles) and hemmed in by ranges soaring as high as 11,800 feet, lies at an elevation of about 6,200 feet. In the southwest, a large depression—the Ararat Plain —lies at the foot of Mount Aragats and the Geghama Range; the Aras River cuts this important plain into halves, the northern half lying in Armenia and the southern in Turkey and Iran.

Armenia is subject to damaging earthquakes . On December 7, 1988, an earthquake destroyed the northwestern town of Spitak and caused severe damage to Leninakan (now Gyumri ), Armenia’s second most populous city. About 25,000 people were killed.

Of the total precipitation, some two-thirds is evaporated, and one-third percolates into the rocks, notably the volcanic rocks, which are porous and fissured . The many rivers in Armenia are short and turbulent with numerous rapids and waterfalls. The water level is highest when the snow melts in the spring and during the autumn rains. As a result of considerable difference in elevation along their length, some rivers have great hydroelectric potential.

Most of the rivers fall into the drainage area of the Aras (itself a tributary of the Kura River of the Caspian Basin), which, for 300 miles (480 kilometres), forms a natural boundary between Armenia and Turkey and Iran.

The Aras’ main left-bank tributaries, the Akhuryan (130 miles), the Hrazdan (90 miles), the Arpa (80 miles), and the Vorotan (Bargyushad; 111 miles), serve to irrigate most of Armenia. The tributaries of the Kura —the Debed (109 miles), the Aghstev (80 miles), and others—pass through Armenia’s northeastern regions. Lake Sevan , with a capacity in excess of 9 cubic miles (39 cubic kilometres) of water, is fed by dozens of rivers, but only the Hrazdan leaves its confines.

Armenia is rich in springs and wells, some of which possess medicinal properties.

More than 15 soil types occur in Armenia, including light brown alluvial soils found in the Aras River plain and the Ararat Plain, poor in humus but still intensively cultivated; rich brown soils, found at higher elevations in the hill country; and chernozem (black earth) soils, which cover much of the higher steppe region. Much of Armenia’s soil—formed partly by residues of volcanic lava—is rich in nitrogen, potash, and phosphates. The labour required to clear the surface stones and debris from the soil, however, has made farming in Armenia difficult.

Because of Armenia’s position in the deep interior of the northern part of the subtropical zone, enclosed by lofty ranges, its climate is dry and continental. Regional climatic variation is nevertheless considerable. Intense sunshine occurs on many days of the year. Summer, except in high-elevation areas, is long and hot, the average June and August temperature in the plain being 77° F (25° C); sometimes it rises to uncomfortable levels. Winter is generally not cold; the average January temperature in the plain and foothills is about 23° F (−5° C), whereas in the mountains it drops to 10° F (−12° C). Invasions of Arctic air sometimes cause the temperature to drop sharply: the record low is −51° F (−46° C). Winter is particularly inclement on the elevated, windswept plateaus. Autumn—long, mild, and sunny—is the most pleasant season.

The ranges of the Lesser Caucasus prevent humid air masses from reaching the inner regions of Armenia. On the mountain slopes, at elevations from 4,600 to 6,600 feet, yearly rainfall approaches 32 inches (800 millimetres), while the sheltered inland hollows and plains receive only 8 to 16 inches of rainfall a year.

The climate changes with elevation, ranging from the dry subtropical and dry continental types found in the plain and in the foothills up to a height of 3,000 to 4,600 feet, to the cold type above the 6,600-foot mark.

The broken relief of Armenia, together with the fact that its highland lies at the junction of various biogeographic regions, has produced a great variety of landscapes. Though a small country, Armenia boasts more plant species (in excess of 3,000) than the vast Russian Plain . There are five altitudinal vegetation zones: semidesert, steppe, forest, alpine meadow, and high-elevation tundra.

The semidesert landscape, ascending to an elevation of 4,300 to 4,600 feet, consists of a slightly rolling plain covered with scanty vegetation, mostly sagebrush. The vegetation includes drought-resisting plants such as juniper, sloe, dog rose, and honeysuckle. The boar, wildcat, jackal, adder, gurza (a venomous snake), scorpion, and, more rarely, the leopard inhabit this region.

Steppes predominate in Armenia. They start at elevations of 4,300 to 4,600 feet, and in the northeast they ascend to 6,200 to 6,600 feet. In the central region they reach 6,600 to 7,200 feet and in the south are found as high as 7,900 to 8,200 feet. In the lower elevations the steppes are covered with drought-resistant grasses, while the mountain slopes are overgrown with thorny bushes and juniper.

The forest zone lies in the southeast of Armenia, at elevations of 6,200 to 6,600 feet, where the humidity is considerable, and also in the northeast, at elevations of 7,200 to 7,900 feet. Occupying nearly one-tenth of Armenia, the northeastern forests are largely beech. Oak forests predominate in the southeastern regions, where the climate is drier, and in the lower part of the forest zone hackberry, pistachio, honeysuckle, and dogwood grow. The animal kingdom is represented by the Syrian bear, wildcat, lynx, and squirrel. Birds—woodcock, robin, warbler, titmouse, and woodpecker—are numerous.

The alpine zone lies above 6,600 feet, with stunted grass providing good summer pastures. The fauna is rich; the abundant birdlife includes the mountain turkey, horned lark, and bearded vulture , while the mountains also harbour the bezoar goat and the mountain sheep , or mouflon.

Finally, the alpine tundra, with its scant cushion plants, covers only limited mountain areas and solitary peaks.

Armenians constitute nearly all of the country’s population; they speak Armenian , a distinct branch of the Indo-European language family. The remainder of the population includes Kurds, Russians, and small numbers of Ukrainians, Assyrians, and other groups.

Armenia was converted to Christianity about 300 ce , becoming the first kingdom to adopt the religion after the Arsacid king Tiridates III was converted by St. Gregory the Illuminator . The Armenians have therefore maintained an ancient and rich liturgical and Christian literary tradition. Believing Armenians today belong mainly to the Armenian Apostolic (Orthodox) Church or the Armenian Catholic Church , in communion with Rome.

Documenting the Armenian Genocide

Essays in Honor of Taner Akçam

- Open Access

- © 2024

You have full access to this open access Book

- Thomas Kühne 0 ,

- Mary Jane Rein 1 ,

- Marc A. Mamigonian 2

Clark University, Worcester, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, Belmont, USA

- This book is open access, which means that you have free and unlimited access

- Honors the life and the work of Taner Akçam, the first Turkish intellectual to acknowledge the Armenian genocide

- Includes twelve contributions from Armenian genocide scholars around the globe

- Sheds new light on the historiography of the genocide, its perpetrators, victims, and bystanders

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in the History of Genocide (PSHG)

19k Accesses

33 Altmetric

Buy print copy

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

About this book

This open access book brings together contributions from an internationally diverse group of scholars to celebrate Taner Akçam’s role as the first Turkish intellectual to publicly recognize the Armenian Genocide. As a researcher, lecturer, and mentor to a new generation of scholars, Akçam has led the effort to utilize previously unknown, ignored, or under-studied sources, whether in Turkish, Armenian, German, or other languages, thus immeasurably expanding and deepening the scholarly project of documenting and analyzing the Armenian Genocide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Marking the Present: Literary Innovation in Ginés Pérez de Hita’s La guerra de los moriscos

The Post-9/11 World in Three Polish Responses: Zagajewski, Skolimowski, Tochman

The Trails of a Counter-Narrative: The Representation of the Years of Lead in Loriano Macchiavelli’s Sarti Antonio Series

- Ottoman Empire

- genocide studies

- genocide denial

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- Thomas Kühne, Marc A. Mamigonian, Mary Jane Rein

Taner Akçam, Istanbul, My Bridge

- Peter Balakian

The Victims of “Safety”: The Destiny of Armenian Women and Girls Who Were Not Deported from Trabzon

- Anna Aleksanyan

Cohabitating in Captivity: Vartouhie Calantar Nalbandian (Zarevand) at the Women’s Section of Istanbul’s Central Prison (1915–1918)

- Lerna Ekmekçioğlu

Mediatized Witnessing, Spectacles of Pain, and Reenacting Suffering: The Armenian Genocide and Humanitarian Cinema

- Nazan Maksudyan

“Special Kind of Refugees”: Assisting Armenians in Erzincan, Bayburt, and Erzurum

- Asya Darbinyan

On the Verge of Death and Survival: Krikor Bogharian’s Diary

Categories and their interstices: the armenian genocide beyond resistance and accommodation.

- Khatchig Mouradian

The Property Law and the Spoliation of Ottoman Armenians

- Raymond H. Kévorkian

Refocusing on—Crimes Against—Humanity

- Hans-Lukas Kieser

Taner Akçam as Scholar-Activist and Armenian-Turkish Relations

- Henry C. Theriault

The Margins of Academia or Challenging the Official Ideology

- Hamit Bozarslan

The Genocide of the Christians, Turkey 1894–1924

- Benny Morris, Dror Ze’evi

Since the Centennial: New Departures in the Scholarship on the Armenian Genocide, 2015–2021

- Ronald Grigor Suny

Back Matter

“This book of essays by leading scholars on the Armenian Genocide is a fitting tribute to Taner Akçam and a major contribution to the field he has helped to define. Embodying the virtues of his pathbreaking work, they present both micro- and macro-perspectives on one of the twentieth-century’s defining events.”

— A. Dirk Moses , City College of New York, USA

“This book is a major contribution to the field of Armenian Genocide Studies. The interdisciplinary aspect of the book - that ranges from gender violence, humanitarianism, the role of cinema, and memoirs, to the economic dimension of the genocide, activism in genocide studies, and historiographic analysis - provides new perspectives on the Armenian Genocide and its repercussions. This groundbreaking volume brings together leading senior and junior scholars in the field whose research will have a tremendous impact on future generations of scholars. The book is a must read to all those interested in understanding the different facets of the Armenian Genocide.”

— Bedross Der Matossian , University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA

Editors and Affiliations

Thomas Kühne, Mary Jane Rein

Marc A. Mamigonian

About the editors

Thomas Kühne is Strassler Colin Flug Professor of Holocaust History and Director of the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University, USA.

Mary Jane Rein is Executive Director of the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University, USA.

Marc A. Mamigonian is Director of Academic Affairs at the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research, USA.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Documenting the Armenian Genocide

Book Subtitle : Essays in Honor of Taner Akçam

Editors : Thomas Kühne, Mary Jane Rein, Marc A. Mamigonian

Series Title : Palgrave Studies in the History of Genocide

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36753-3

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : History , History (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2024

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-031-36752-6 Published: 29 December 2023

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-031-36755-7 Published: 29 December 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-36753-3 Published: 28 December 2023

Series ISSN : 2731-569X

Series E-ISSN : 2731-5703

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XII, 308

Number of Illustrations : 10 b/w illustrations

Topics : History of the Middle East , Modern History , Historiography and Method

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Armenia from ethnogenesis to the dark ages: from a world history perspective: home, the class syllabus.

This guide will introduce select sources on Ancient and pre-modern Armenian history to its users.

Primary Sources: Ancient Period

- Strabo's Geographica-see: Book XI, Chapter 14

- Cassius Dio Roman History : Epitome of Book LXXI (On Armenia)

- Récit des malheurs de la nation arménienne. Aristakēs, Lastiverttsʻi, Vardapet, active 11th century.; Canard, Marius, editor.; Pērpērean, Hayk, 1887-1978.

Subject Guide

Persian Sources on Armenian History

- طبقات ناصرى / تاءلىف منهاج سراج جوزجانى ؛ تصحىح، مقابله و تحشىۀ عبد الحي حبىبى./ Ṭabaqāt-i Nāṣirī by Minhāj Sirāj Jūzjānī, 1193-1266. ISBN: 9789643314231

- زیج ایلخانی

Armenian E-Books from Haybooks

- On the Origins of the Armenian People

Հայ ժողովրդի ծագման ու հնագույն պատմության հարցեր / Ռաֆաել Իշխանյան, Երևան 1988

- On medieval Armenia

Արաբական արշավանքները Հայաստանում , in Մանր Հետազոտություններ / Հակոբ Մանանդյան (Hakob H. Manandyan – b. 1873), Երեվան 1932 (p. 22-64). See the table of contents (on Gallica)

Մամիկոնյանների ծագման ավանդությունը և պատմական իրականույթւոնը , Ա. Քեշիշյան, in Հայոց պատմության հարցեր, Հ. 1, 1997 (on Armenian Academic Research)

Ասորական աղբյուրներ , Հ. Ա, series “Օտար աղբյուրները Հայաստանի և հայերի մասին” Հ. 8, Երևան, 1976 (on Armenian Academic Research)

On glass and metal craftmanship in medieval Armenia : Միջնադարյան Հայաստանի գեղարվեստական մետաղը IX-XIII դդ. ։ Միջնադարյան Հայաստանի հաղճապակին IX-XIV դդ ., Նյուրա Հակոբյան, Աղավնի Ժամկոչյան, Երևան : ՀՍՍՀ ԳԱ հրատ., 1981

- On Armenian Cilicia

Հայկական Կիլիկիա / Վահան Մ. Քիւրքճեան, Նիւ Եորք 1919 (139 p.), with a map . See the table of contents (on Gallica)

Other guides related to Armenian History

- Hist 177B: Armenia: From Pre-modern Empires to the Present

- Armenian Studies

Article Databases

Armenian Manuscripts

- Armenian Manuscripts at the French National Library

- Artstor: Armenian Manuscripts

- Manuscripts in the Libraries of the Greek and Armenian Patriarchates in Jerusalem

Armenian Sources

- Patmut'yun Nahangin Sisakan = History of the State of Sisakan

Primary Sources: Byzantine/ Sassanian Period

- "Vahram's Chronicle of the Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia, during the time of the Crusades"

Select Arabic Sources

- لكامل في التاريخ - ابن الأثير الإمام العلامة أبي الحسن علي بن أبي الكرم محمد بن محمد بن عبد الكريم بن عبد الواحد الشيباني المعروف بابن الأثير الجزري الملقب بعز الدين 630 هـ

- كتاب التحفة الملوكية فى الدولة التركية : تاريخ دولة المماليك البحرية فى الفترة من 711-648 هجرية / تأليف بيبرس المنصورى ؛ نشره وقدم له ووضع فهارسه عبد الحميد صالح حمدان.; Kitāb al-tuḥfah al-mulūkīyah fī al-dawlah al-Turkīyah : tārīkh dawlat al-Mama On Mamluk History (Baybars al- Mansuri's (d. 1324-25) Kitab al-Tuhfa al-mulukiyya jil-dawla al-Turkiyya)

Sources on Armenian Art and Monuments

Books from catalog.

Important Islamicate and Islamic Manuscripts Databases

- Last Updated: Apr 1, 2024 4:26 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/armenia

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

Harvard Squared | Explorations

“Armenian creativity, culture, and survival”

A museum reflects an ancient civilization and the modern global diaspora..

January-February 2022

The impressive two-tiered modern interior of the Armenian Museum of America Photograph courtesy of the Armenian Museum of America

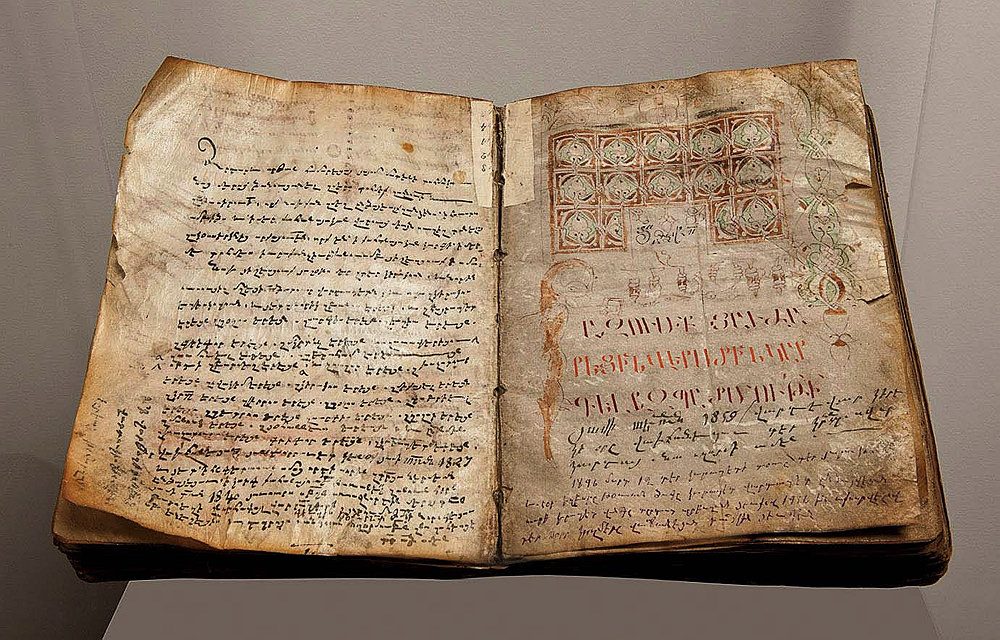

In 1207 an elderly scribe in the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia completed the Garabed Gospel. Although blinded by the 11-year undertaking, he completed the 250 inked, goat-skin pages, with decorative marginalia, at a monastery near what is now southern Turkey and gave it to a priest. For the next 700 years, the manuscript was passed down through that family lineage of priests, serving as a sacred object, according to the Armenian Museum of America, in Watertown, Massachusetts, where the volume is now on display. “If one became sick, one would ask the family for ‘the blessing of the book’ to cure their disease. A supplicant would rub a piece of bread or a rag on the Gospel Book,” a museum plaque explains. “If the bread was eaten by the afflicted, or the rag was worn against their body, it was thought to cure the disease.”

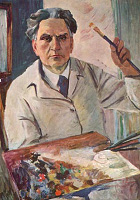

It is the museum’s oldest book, says executive director Jason Sohigian, A.L.M. ’11, and survived the looting and destruction of other texts, art, cultural objects, and whole villages by the invading Turks over the years. The museum’s collection of more than 25,000 objects elucidates some 3,000 years of Armenian history and culture, from the early days of Christianity (Armenians were the first to accept Christianity as a state religion) to the contemporary global diaspora. That includes 5,000 ancient and medieval coins and pre-Christian pottery and metalwork, along with liturgical manuscripts and objects, rugs, lacework, embroidery, and artifacts from the World War I-era genocide. More contemporary are the museum’s series of famous portraits by Yousuf Karsh, underground works from the Soviet era (donated by Norton Townshend Dodge, Ph.D. ’60) and, surprisingly, a handful of oil paintings by the American pathologist, and pioneering right-to-die with dignity proponent, Jack Kevorkian, whose mother escaped the genocide.

“Many of the objects in our collection and on display are survivors of history,” says Sohigian. “Armenians have inhabited those lands for thousands of years, and our cultural heritage has been under threat especially in recent centuries. Our museum is unique in that it preserves and displays many of these artifacts that tell the story of Armenian resilience, creativity, culture, and survival over millennia on the territory known as the Armenian Highland.”

That mission, of bridging gaps between ancient and modern identities, “is not easy or unproblematic, as we know,” says Tufts professor of art and architecture, Christina Maranci, Dadian and Oztemel chair in Armenian art and architectural history, and an academic adviser to the museum. “It is best, in my view, to let the objects speak for themselves,” she says. “The Garabed Gospels…does this well: its colophon records its initial production by the scribe Garabed, successive owners and users over generations, indeed centuries, as well as its vandalization during the Genocide.”

The museum’s “extraordinary collection,” she adds, is both under-researched and under-studied, but is instrumental in chronicling and bearing witness to rich aspects of world history. She highlights the late fifteenth-century hymnal illuminated by Karapet of Berkri, a famous medieval artist and scribe from the Vaspurakan region (the cradle of Armenian civilization, now within the borders of Turkey and Iran), and an eighteenth-century altar curtain made from wooden block prints for a church of Saint George in Mardin as “testifying to circulation of objects across the Armenian communities in the Ottoman Empire.” A priest’s cope ( shurchar ), made in Surabaya for a wealthy Armenian trading family, as one of her students discovered during a research seminar, “combines traditional Indonesian batik fabric with an Armenian inscription, speaking eloquently to the dynamics of cultural exchange in the early modern world, and the role of Armenians within it.”

Scholarly value aside, the museum is a powerful experience for visitors, no matter how familiar they are with Armenian culture and history. It’s a testament not only to the layered ancient world, but to a peoples’ resilient drive to survive and flourish despite historic genocide and other forms of destruction. The local effort to find and preserve elements of this heritage began in 1971 when a small group of Armenian Americans first gathered contributed items in the basement of the First Armenian Church in Belmont, Massachusetts.

The state has long been home to the nation’s second-largest Armenian American population, with about 30,000 residents of Armenian heritage living primarily in Boston, Worcester, and Watertown. Los Angeles is home to 205,000 residents of Armenian descent (Cherilyn Sarkisian, better known as Cher, and the Kardashian clan among them), but has no museum. The Watertown institution’s founders eventually bought a former bank building, a brutalist structure designed by Ben Thompson, of The Architects’ Collaborative, in Cambridge, stored valuable items in existing vaults, and began opening exhibits to the public in 1991, the same year Armenia declared independence from the Soviet Union.

Preservation of materials connected to Armenia is a continuing effort, Sohigian notes. In September 2020, the museum took a stand against the “resumption of war” and the threats against Armenian culture in the Artsakh region, expressing “solidarity with colleagues in the scholarly and cultural heritage community around the world, who are calling attention to the threat of cultural genocide and ethnic cleansing in Artsakh.” The 44-day war in that region, also known by its Russian name Nagorno Karabakh, began on September 27, 2020, and was led by the Republic of Azerbaijan with Turkey’s military support and Syrian jihadist mercenaries. The war was halted by a trilateral agreement, and Russian peacekeeping troops currently occupy the region, although remaining Armenians face a precarious future.

Joining the effort to draw attention and aid to the political crisis, the museum spotlights, near the entrance, an artful pair of #PeaceForArmenians cleats. Donated for the NFL’s “My Cleats, My Cause” program by the New England Patriots’ director of football/head coach administration Berj Najarian, an Armenian American, the cleats are painted with Armenian iconic imagery by Massachusetts artist Joe Ventura, and were auctioned off to support the Armenia Fund. They were bought and donated by museum president Michele Kolligian and vice president Bob Khederian. Nearly all of the items have been gifts, notably from Paul and Vicki Bedoukian.

Among the most stirring objects are in the exhibit about the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1916. During this period, Armenians living in the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire were subjected to arrest and deportation, and otherwise systematically annihilated through massacres, starvation, exposure, and illness. Many were forced to walk to desert regions where they died along the way. The events were finally publicly recognized as genocide by President Joe Biden last year. “The global diaspora was the result of the Armenian Genocide, and the survivors of that generation went on to thrive and prosper,” Sohigian says. “This is a source of pride for us, and we are honored to tell this story to the world.”

Walls depict maps and photographs interspersed with an extensive chronology of both the historic context for the genocide, and the events themselves. But artifacts convey the human toll. “This is an outfit worn by a child victim of the 1915 genocide,” Sohigian says during a museum visit. “And this eighteenth-century Bible was found buried in the Syrian desert, Der Zor,” where deportees died. There are also human bone fragments, a metal collar used as an instrument of torture, handwritten letters, and a folk art crafted by survivors.

The first wave of Armenians to Massachusetts grew out of the spread of American Protestant missionary schools across Anatolia, according to the genocideeducation.org project, but then worsening economic conditions, violence, and forced conscription into the Ottoman army led to a second wave in the 1890s. “The most important destination…was Watertown, where the new Hood Rubber factory opened its doors in 1896. Coinciding with the exodus of Armenians from the 1890s massacres, a direct pipeline developed between the Armenian provinces and east Watertown.” Thousands more arrived in flight from the 1915 genocide such that by 1930 more than 3,500 Armenians lived in Watertown—nearly 10 percent of the population. The community still thrives today, with churches, grocers, a cutural center, and a school.

The museum owns hundreds of beautifully hand-woven rugs, several of which are on display, along with traditional apparel and examples of fine needlework. Visitors will see a velvet wedding dress with gold-lace embellishments and a woven belt typical of the women’s clothing of Erzurum, a once-thriving Armenian city that’s now part of eastern Anatolia, Turkey. Embroidered textiles from Marash, in Cilicia, now southeastern Turkey, feature interlaced stitching depicting architectural and natural motifs. There’s also white lacework, liturgical clothing and objects, like the 1813 Hmayil, an illustrated scroll featuring prayers and quotes to help ward off dangers and sickness, and musical instruments. Among them is the indigenous Armenian duduk, an ancient double reed woodwind piece made from apricot wood. Striving to connect this rich past of ancient kingdoms and global migration to the present, the museum typically hosts art classes and year-round in-person activities featuring Armenian food, music, dance, and scholarly talks on its huge, skylighted third floor. Planning is under way for 2022 programs; check the website calendar at armenianmuseum.org for details.

Within that event space, look for the two galleries of striking contemporary art. Dissident Collection of Armenian Art features a painting by the well-regarded Sarkis Hamalbashian, and about 10 works produced in Soviet-era Armenia. They were donated by the foundation for the economist and collector Norton Townshend Dodge, who first traveled to the Soviet Union in 1955, ostensibly as part of his Harvard dissertation, and eventually, covertly, amassed one of the largest collections of Soviet art outside of the Soviet Union. (His activities are narrated in John McPhee’s 1994 The Ransom of Russian Art. )

Hanging in the adjacent gallery are the graphic, surrealist Kevorkian works. In addition to his active support of physician-assisted suicide (for which he was convicted of second-degree murder in 1999 and served eight years in prison), Kevorkian was also a jazz musician, composer, linguist, and painter. Of the art displayed, most salient, and framed using human blood, is 1915 Genocide 1945. Kevorkian’s own explanatory label reads, in part: “No collective human action can match the depravity of race murder. To call it bestial would be unfairly lowering the beast…Any such attempt (including this painting) would never convey the real meaning of unlimited murder for the purposes of national extinction, beginning with the American Indians.”

This winter, the museum adds to these contemporary galleries a multimedia exhibit anchored by its recently acquired Armenian cross-stone, known as a khachkar . The object reflects a medieval art form unique to Armenia, and was carved in 2018 by sculptor Bogdan Hovhannisyan for the Smithsonian Institute’s Folklife Festival. “It’s a connection between a modern artist and a tradition; if you go to Armenia now, you will see artists carving these crosses in their workshops,” Sohigian says. “And all these things, the monuments, artifacts, relics, art, are actively being destroyed by Turkey and Azerbaijan now.”

The cross-stone, like the Garabed Gospel painstakingly created in the thirteenth century, stands to preserve cultural history and the collective experience of a displaced, dispersed people. Although the manuscript was seized by authorities when older members of the extended Der Garabedian family, which held the Holy Book for 39 generations, were killed during the genocide, a surviving relative paid a ransom for its return. In 1927, he gave it to a nephew who had emigrated to America, and his surviving daughter, Julia Der Garabedian, entrusted it to the museum. “If we agree that cultural heritage is a human right,” Christina Maranci says, “then we should respect, protect and learn from those communities whose cultures have faced destruction.”

You might also like

Breaking Bread

Alexander Heffner ’12 plumbs the state of democracy.

Reading the Winds

Thai sailor Sophia Montgomery competes in the Olympics.

Chinese Trade Dragons

How Will China’s Rapid Growth in the Clean Technology Industry Reshape U.S.-China Policy?

Most popular

Pioneer Valley Bounty

A local-food lovers’ paradise

The World’s Costliest Health Care

Administrative costs, greed, overutilization—can these drivers of U.S. medical costs be curbed?

More to explore

American Citizenship Through Photography

How photographs promote social justice

John Harvard's Journal

Harvard Philosophy Professor Alison Simmons on "Being a Minded Thing"

A philosopher on perception, the canon, and being “a minded thing”

Food Tours and More in Pioneer Valley Massachusetts

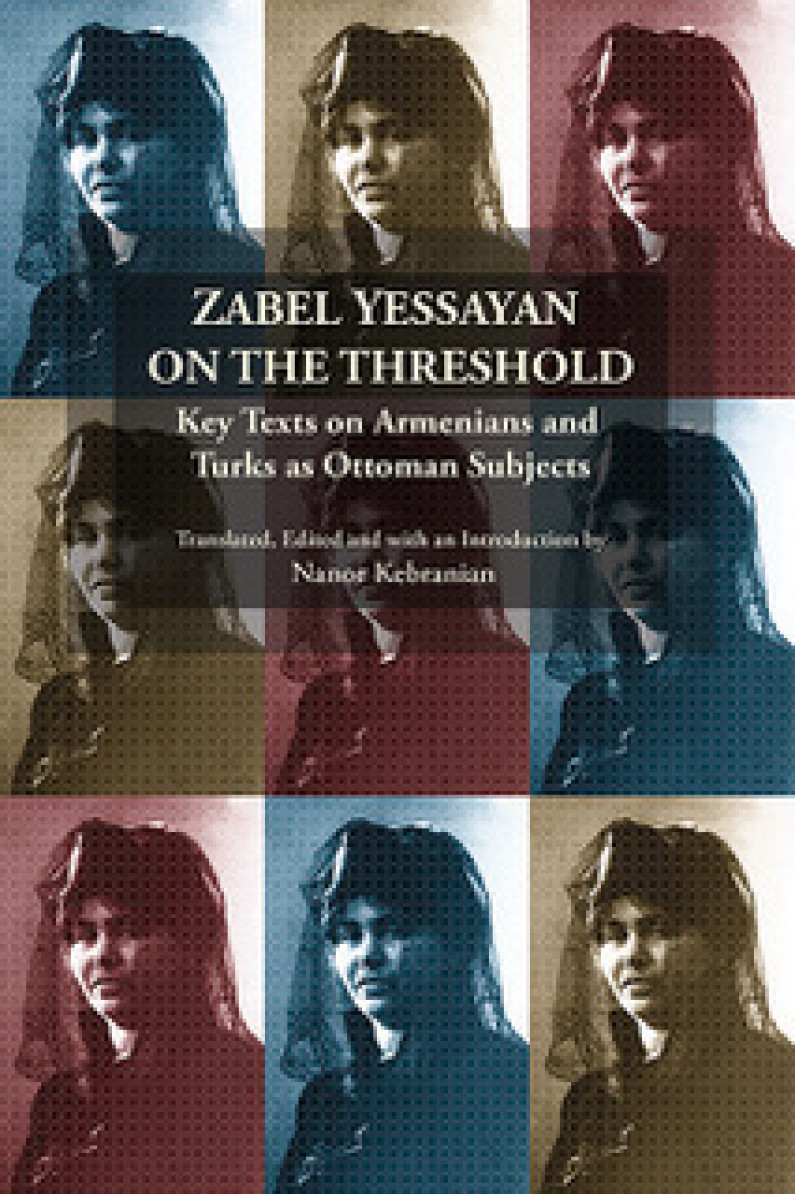

The Veil of History: Translating across the Armenian Genocide Divide

Posted on March 11, 2024

Essay by Nanor Kebranian

Since the Armenian Genocide during the First World War, translation has become a source of cultural preservation for survivors and their increasingly assimilated non-Armenophone descendants. This marks a significant shift from translation’s role prior to the Genocide. In the 19 th century, Armenians in the Ottoman Empire employed translation into Armenian as a formative process for developing and standardizing the so-called ‘Western’ branch of modern Armenian language and literature. Translators were not only instrumental in coining new terms or drawing additional meanings from existing Armenian words, but they also applied and promoted the spread of standardized grammatical forms in Western Armenian literature. This so-called ‘Western’ variant was unique to what was deemed ‘Western’ Armenia encompassing the autochthonous Armenian territories of the Ottoman Empire and various cultural hubs abroad. The mutually comprehensible ‘Eastern’ branch developed in the Armenian Caucasus – now Armenia – and the communities of Persia – now Iran. After the Genocide, Western Armenian became the mainstay of Diaspora Armenian culture – consisting primarily of survivors and their descendants –, [1] whereas Eastern Armenian constituted the language of Armenia proper. [2] Western Armenian literature, including translations from other languages, initially flourished in the post-War Diaspora. But cultural – and especially linguistic – assimilation has ultimately led to the precipitous decline of Western Armenian. It now appears on UNESCO’s list of endangered languages. In this climate of precarity, translation from Armenian has consequently attained redoubled force as a powerful medium of cultural continuity and conservation. The question of what and how to translate, however, remains to be answered.

Despite the Diaspora’s evident commitment to cultural continuity through various social and educational organizations, post-Genocide translation from Armenian into other languages has mostly remained an afterthought. An overview of what has been produced in English and French even in the most active cultural centers of the Armenian Diaspora – notably, Paris, Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and Fresno – reveals a disconnected patchwork consisting of monographs or collections representing a few notable authors from the post-World War II canon of Western Armenian literary history; anthologies organized by genre; or references and textbooks with translated excerpts. These translations are important for cataloguing names and contexts. But, with very few exceptions and aside from highlighting linguistic-literary trends or underscoring a specific writer’s innovations, they grant few insights into the conceptual and epistemic wealth of Armenian literary culture in the Ottoman Empire. What is preserved through such translations, then, are fragments of a cultural façade. In that respect, they function more as public monuments to the dead and gone rather than as gateways into the throbbing intellectual world of a living Armenian past. Out of place and out of time, they invite but a passing glance.

Before the Genocide, translations did not compartmentalize, preserve, or mummify Armenian literature; they enlivened it. Of course, these consisted of translations into Western Armenian. They included predominantly classics of the Western humanist canon, but also significant treatises on progressive politics and social reform. Less frequently, translators tackled major religious, philosophical, and literary texts from neighboring regions in the Middle East as well as from East and South Asia. Their collective effort has been described as a constitutive aspect in the broader project of generating a national awakening inspired by the tenets of the 1848 French Revolution. Historical accounts of this process accordingly tend to present it exclusively as a mimetic event with Armenians attempting either to graft the Enlightened West onto Armenian culture or to massage Armenian thought to fit the contours of existing Western conceptual paradigms.

But this somewhat abridged – and patently underestimating – chronicle of Armenian intellectual history overlooks the fact that many translators collectively perceived translation as a self-consciously performative strategy geared at (re-)building and manifesting consensus, sociality, and solidarity. This was not a matter of interpolating Western principles over Armenian ones, but rather of revealing and restoring these values’ indigenous origins prior to the (economic, social, political, and linguistic) fractures wrought by the communalist Ottoman system. A meta-reading of these translators’ text selections, commentaries, and prefatory statements alongside their activism and institutional initiatives reveals a sophisticated enactment of social reconstitution. This was done with the awareness – especially but not only since the Ottoman State’s authoritarian turn in the 1880s – that their efforts could cost them their livelihoods, or even lives. Translation could indeed become a matter of life and death if perceived as politically subversive discourse. But, if translators – and the broader world of progressive Armenian print culture – took these chances, it was with the understanding that a greater looming danger was making the very conditions of their entire nation’s – and hence, of their own – existence virtually impossible.

This was the threat of fragmentation and assimilation symptomatized through language loss, inter-confessional strife, economic dispossession, and State repression. By the turn of the 20 th century, some began to name the last and greatest of these threats, ‘extermination’ – pnachnchum . The word ‘genocide’ – coined by Raphael Lemkin in his 1944 Axis Rule in Occupied Europe – did not yet exist. And Armenians from across the social and political spectrum assumed the task of translating against the exterminationist will pervading – and imperiling – their lives. One editor went so far as to engage in what I term elsewhere, ‘literary diplomacy.’ In 1914, just one year before the Armenian Genocide was put into effect, none other than the purportedly ‘nationalist’ writer, Rupen Zartarian, republished and amplified his compilation of translations from Ottoman-Turkish works into Western Armenian. It was, as his preface indicates, the very first such initiative to place the two neighboring peoples’ literatures side-by-side. Zartarian’s rationale? The hope of mutual knowledge and hence, ‘harmony’ – nertashnagutiun . Zartarian was among the first wave of Armenian intellectuals who were then arrested on April 24, 1915 and executed on the deportation route a few months later. Remarkably, except for a couple of passing or synoptic references, Zartarian’s groundbreaking compilation of translations from Ottoman-Turkish has been exceedingly underestimated or effectively expunged from post-WWII Ottoman and Armenian literary historiography. But Zartarian’s intervention can be read as an important signpost on the way to dispersion. It provides some guidance on translating with purpose; that is, in a more worldly way than the act of preserving or memorializing a few names and events.

Over the past two decades, translations of Armenian literature into Turkish have tended increasingly towards that direction. Many of the often incredibly well-received publications of Aras Yayıncılık, for example, reveal a more deeply engaged approach to translation, one that deliberately confronts and contests official Turkish narratives of the Armenian presence – or lack thereof – in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. Importantly, most of these works highlight the little-known post-genocide experience of marginalized Armenians remaining in Turkey, especially the tensions and intricacies of multiethnic coexistence.

However, an important element in that story – its antecedent, as it were – remains to be translated. It consists of original writings and other projects – such as Zartarian’s noted earlier – that attempted to breach the Armeno-Turkish divide both before and after the Genocide. In the past decade, two such works have appeared through Aras Publishing House: the republication of a 1913 collection presenting contemporary Armenian literature (including Zartarian’s) in Ottoman-Turkish translation, alongside commentaries by various Ottoman-Turkish authors; and the Turkish translation of Zabel Yessayan’s 1925 novella, Meliha Nuri Hanım , written from the first-person standpoint of an Ottoman-Turkish woman volunteering as a nurse in WWI Gallipoli. While they constitute significant breakthroughs, these works have deeper literary and social connections that are not immediately apparent in their discrete appearances. One of the tasks – although, by no means the only one – of Armenian literature’s translation today is to uncover those veiled – at times, quite deliberately – features of Ottoman/Armenian literary history. It is a difficult – but not impossible – task, since few guiding principles and precedents exist. At stake is not just the now tired cliché of fostering Armeno-Turkish dialogue and mutual understanding. More importantly, for a culture and literature on the brink of extinction – and for a world that is becoming increasingly siloed through tribalist loyalties – is access to the intuitive pull by which to maintain a regenerative emotional and conceptual link to these cultural resources.

Zartarian the polyglot and multilingual translator understood the value of forging this link. As did others, such as the Ottoman-Armenian woman author, Zabel Yessayan, who also wrote and translated between French and Armenian. It seems appropriate then to reorient Armenian translation in the Diaspora – and in the liminal zone of Armenian Turkey as well – through their long forgotten or ignored attempts at crossing the Armeno-Turkish divide. This process is already underway in English, beginning with two edited collections of translated works from Yessayan: Captive Nights: From the Bosphorus to Gallipoli with Zabel Yessayan (California State Frenso, 2021) and Zabel Yessayan on the Threshold: Key Texts on Armenians and Turks as Ottoman Subjects (Gomidas Institute, 2023). A critical edition of Zartarian’s Ottoman-Turkish literary compilation is soon to follow. Importantly, none of these initiatives could have been possible without the institutional support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and its mission to recenter the cultural significance of Armenian translation. These projects have culminated from years of unaided inquiry into the psychic life of Ottoman-Armenian subjecthood, and especially into the syntheses of Armeno-Turkish coexistence in the hierarchically organized Ottoman state. Since the Genocide, few writers and scholars have attempted to broach that delicate topic – as though no such syntheses were ever possible. Would that still be true had the 19 th century Armenian culture of purposeful translation survived the ruptures of history? One can imagine an alternate reality, where post-Genocide Armenian society recognizes the veritably translational landscape of Ottoman belonging and attunes itself to the boundary-crossing literary translations that enriched it.

[1] While Armenians had for centuries enjoyed a diasporic presence especially in various global economic hubs, this post-genocide Diaspora formed with the dispersal of survivors from their ancestral homes in the Ottoman Empire to various host countries. Over the course of the early twentieth century, the survivors’ descendants created significant communities in the Middle East, Europe, and the United States, employing Western Armenian as their ‘national’ language.

[2] The fall of the Soviet Union has altered the Diaspora’s linguistic/literary profile, however, as the exodus of Armenians from the independent post-Soviet State has enabled Eastern Armenian to take root abroad. Eastern Armenian remains relatively strong thanks to Armenia’s statehood.

Nanor Kebranian is a Research Fellow at the Faculty Centre for Transdisciplinary Historical and Cultural Studies, University of Vienna (2023 - 2024). She was Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow and Visiting Scholar in the History Programme at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore (2020 - 2021). Prior to this appointment, she was Postdoctoral Research Assistant in Theory, History, and Human Rights in the HERA-funded project for Memory Laws in European and Comparative Perspective in the School of Law at Queen Mary University of London. She also served as Assistant Professor in Columbia University's Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies, where she researched, published, and taught on the history of the Middle East, literary studies, human rights, and Armenian culture. She completed her doctorate at the University of Oxford with fellowships from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation and Oxford's Clarendon Fund. In 2023, she published a collection of translations from the work of Ottoman-Armenian woman author, Zabel Yessayan (1878 - 1943?), Zabel Yessayan on the Threshold: Key Texts on Armenians and Turks as Ottoman Subjects (London: Gomidas Institute, 2023). She is currently completing her first monograph on the Armenian literature of Ottoman subjecthood (1860 - 1945) with funding from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, as well as a translation of the influential and previously untranslated memoir — Twelve Years Away from Constantinople (1896 - 1909)— by Ottoman-Armenian intellectual and activist, Yervant Odian (1869 - 1926), with funding from the Dolores Zohrab Liebmann Fund.

More from Exchanges

- Translators Note: Exchanges Audio

- Briefly Mentioned

- World Literature in the Making

Translation on the Margins of Possibility: Encounters with Satire

Review: Pyre

Untranslatability: Ravens and Tigers and Camels, Oh My!

Translation & language justice: a conversation with jen/eleana hofer.

Review: Greek Lessons

Privacy Information Nondiscrimination Statement Accessibility UI Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

Armenia’s existential moment

- December 5, 2023

Thomas de Waal

- Themes: Geopolitics

Armenia is facing its most precarious moment in three decades. The loss of Karabakh, a region with a centuries-old history of Armenian habitation and heritage, will reverberate for generations.

/https%3A%2F%2Fengelsbergideas.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F12%2FNagorno-Karabakh-1.jpg)

Many people in the West are looking out on the global landscape with a grim sensation that the international order has broken down, conflicts are flaring up unchecked and we have arrived in a multi-polar world of a brutal kind.

In the South Caucasus many would say that this is the world they live in already. When the Soviet Union came to an end in 1992, a post-Cold War peace never properly arrived in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. The region was torn apart by three ethno-territorial conflicts. In 2020 the biggest dispute of the three, the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorny Karabakh , resumed after a 26-year pause, with Azerbaijan winning a military victory.

On 19 September Azerbaijan launched a new lightning operation to seize the Armenian-run region of Nagorny Karabakh, which it last administered in the late Soviet era. The entire Armenian population — more than 100,000 people — fled their homes. On 15 October, Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev, delivered a victory speech, dressed in camouflage fatigues, in an empty city, Karabakh’s local capital, Stepanakert, renamed Khankendi by Azerbaijan. ‘Today, all the people of Azerbaijan are genuinely rejoicing. All the people of Azerbaijan are praising Allah,’ said Aliyev , belying by omission the prospect that Karabakh Christian Armenians could be citizens of Azerbaijan.

Aliyev’s speech was one of personal redemption, made on the 20 th anniversary of his first inauguration as president in 2003. The whole visit to the deserted city was a one-man show, with the president filmed alone, walking around the empty office of the Karabakh Armenian administration and, like a triumphant Roman victor, trampling over their flag.

The symbolism was all about national rebirth and revanchism. Aliyev’s speech was made in the same square in which Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan had told crowds in August 2019, ‘Artsakh [the Armenian name for Nagorny Karabakh] is Armenia, full stop.’ Aliyev’s main reference point was to 1994, the year when Azerbaijan suffered a bitter defeat in the first Karabakh war of the 1990s, the culmination of many rounds of ethnic cleansing and mass displacement by both Armenians and Azerbaijanis, in which Azerbaijan ultimately paid the heaviest price. Years of humiliation, both personal and national, were being expunged.

The Azerbaijani leader was actually reaching further back, to the 1920s. Having once promised the Karabakh Armenians high levels of territorial autonomy, he has now declared ‘Nagorny (Mountainous) Karabakh’ abolished as both a name and as an Armenian-led autonomous region. He has thereby cancelled an arrangement first created by the Bolsheviks in 1921, and declared it an act of sabotage against Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan is busy rewriting a whole century-old script.

The years 1917-21 were the formative era for the South Caucasus, in which the modern political contours of the region were first drawn, and it was a theatre of inter-ethnic and proxy conflict. Much of what happened then – and seemed to be settled – is being revisited again.

The lessons of that era are set out in the classic history The Struggle for Transcaucasia , written by Firuz Kazemzadeh and published in 1951. His story begins in 1917, at a moment that rhymes with the present: Russian power collapsed in the Caucasus along with the end of the tsarist empire, allowing Armenians, Azerbaijanis and Georgians to declare independence. It ends in 1920-1 with a turn of events which is much less likely: a Russian reconquest at the hands of the Bolshevik 11 th Army, which overturned the newly independent republics of Azerbaijan, then Armenia and finally Georgia in less than a year.

The story in between is of almost uninterrupted conflict across the entire region. Feckless local leaders won pieces of territory but weakened their new national projects in the process. The Bolsheviks’ eventual appeal to the population, such as it was, was as a strongman arbiter, who pacified the region and ended these fratricidal conflicts.

The Western powers promised more than they delivered. The European powers recognised the independence of the three Caucasus states only when it was too late. The British made empty reassurances that border disputes would be settled at the Paris Peace Conference, only to pull out of the region in 1921 with a few statements of regret. ‘British policy toward the new states lacked consistency, and was determined by the exigencies of the moment rather than any long-term plans,’ writes Kazemzadeh.

It is also a tale of collusion between the two former imperial powers in the region,Russia and Turkey, who both dared to put troops on the ground. Mustafa Kemal’s nascent Turkish Republic helped facilitate the Bolshevik takeover. Kemal’s actions sold out the young Turkic kin-state of Azerbaijan, fatally weakened Armenia and adopted ‘benevolent neutrality’, which allowed the Red Army to capture independent Georgia. In return, Turkey got to sign an agreement with Russia, the Treaty of Kars, in October 1921, which allowed it to keep the territorial conquests it had taken from Armenia.

Aliyev’s military operation in September in Karabakh was something right out of The Struggle for Transcaucasia . He seized the moment to achieve something Azerbaijan had tried and failed to do in 1918-20 and 1991-2: drive out the Armenians and make Karabakh a fully Azerbaijani territory.

The calculation was that Russia and Turkey are still the key outside powers and you get things done by cutting deals with them. Despite their overt rivalry, Russia and Turkey have shared interests in the South Caucasus. Seçkin Köstem (before the latest developments) called the relationship one of ‘ managed regional rivalry ’. As Vladimir Lenin and Mustafa Kemal before them, Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan disagree on much, but both feel a resentment towards Western hegemony, which positions them as what Fiona Hill and Omer Taspinar have called the ‘ axis of the excluded ’.

The war in Ukraine has strengthened Turkey’s bargaining power. Turkey is playing different sides, giving military support to Kyiv, throwing an economic lifeline to Moscow and making its case as the indispensable East-West hub. For its part, Russia is weakened by its war to the point where it decided to abandon its traditional role as the main arbiter of the Karabakh conflict as leverage over Armenia and Azerbaijan. In September 2023, for the first time in its post-Soviet history, it stood down the peacekeeping force it had sent to Karabakh in 2020, and allowed the Azerbaijani military to attack, unimpeded. Those who celebrate this as a defeat for Russia in the Caucasus are probably getting ahead of themselves. Laurence Broers calls Moscow’s pivot to Azerbaijan and abandonment of Karabakh and Armenia ‘managed decline’, in which it is redefining its goals in the region in order to stay in the game.

Azerbaijan’s bet was also that, as in 1920, the West is a paper tiger, when the soldiers start marching. Since the end of 2021 Azerbaijan and Armenia have been engaged in a diplomatic process, led first by the European Union and then jointly by Brussels and Washington, to finalise a ‘peace agreement,’ a bilateral treaty normalising their relations, demarcating the border and opening closed road and rail routes. A lot of progress was made, but the future of Armenian-populated Karabakh inevitably hung over the whole process. The Armenian government recognised that Karabakh would be part of Azerbaijan so long as the ‘rights and security’ of its Armenian residents would be respected. As Azerbaijan tightened its grip on the enclave, the European and US mediators, urged restraint and tried to facilitate direct talks between the Karabakh Armenian leaders and Baku.

We will probably never know how serious Aliyev was about this Western diplomatic track, or whether he was just keeping his options open until he was able to cut a better deal with the Russians. In any case, he launched his blitzkrieg in September, after reportedly making many reassurances to senior Western officials, such as EU Council President Charles Michel that he would not resort to force. (The Azerbaijanis arrested six of the local Armenians leaders they were supposed to be talking to. They are now in jail in Baku.)

Negotiations over a ‘peace agreement’ between Baku and Yerevan continue even though the Western-mediated process has not yet resumed. The Azerbaijanis pulled out of scheduled talks in Washington, alleging that the US is biased against them. Azerbaijan says there should just be a bilateral agreement without outside mediators; the Armenians say they are not against this but, in circumstances where they are much weaker, they want international guarantees on its implementation.

The cooling towards the West is also about the contrast between Armenia’s (imperfect) democracy, now turning West for support, and Azerbaijan’s Russia-style single-party autocracy. Aliyev’s regime is becoming even more repressive . It has arrested several dissident voices and journalists, and accused the US embassy of recruiting American-educated Azerbaijanis as spies.

In a vacuum that opens up if Western diplomacy stalls, several candidates are keen to step in. Iran, the third big regional neighbour, is trying to assert a role it has lacked in the South Caucasus since the end of the Soviet Union. The Iranians are talking up a so-called ‘3+3 format’, a mechanism devised by the three big neighbours to discuss the future of the region.

In substance, 3 + 3 is more accurately a 3 + 2. Georgia refuses to participate in a format that includes Russia. Armenia is very lukewarm, leaving Azerbaijan as the only one of the regional three to express any enthusiasm, talking of ‘regional solutions to regional problems’.