How To Write An Editorial (7 Easy Steps, Examples, & Guide)

Writing an editorial is one of those things that sounds like it should be pretty straightforward. Easy, even.

But then you sit down to start typing. Your fingers freeze over the keyboard. You gaze into the perfectly blank white space of your computer screen.

Wait , you think. How do I write an editorial ?

Here’s how to write an editorial:

- Choose a newsworthy topic (Something with broad interest)

- Choose a clear purpose (This will guide your entire process)

- Select an editorial type (Opinion, solution, criticism, persuasive, etc)

- Gather research (Facts, quotes, statistics, etc)

- Write the editorial (Using an Editorial Template that includes an introduction, argument, rebuttal, and conclusion)

- Write the headline (Title)

- Edit your editorial (Grammar, facts, spelling, structure, etc)

In this article, we’ll go through each of these steps in detail so that you know exactly how to write an editorial.

What Is an Editorial? (Quick Definition)

Table of Contents

Before we jump into the mechanics of how to write an editorial, it’s helpful to get a good grasp on the definition of editorials.

Here is a simple definition to get us started:

An editorial is a brief essay-style piece of writing from a newspaper, magazine, or other publication. An editorial is generally written by the editorial staff, editors, or writers of a publication.

Of course, there’s a lot more to it than simply dashing out an essay.

There is the purpose, different types of editorials, elements of a good editorial, structure, steps to writing an editorial, and the actual mechanics of writing your editorial.

“In essence, an editorial is an opinionated news story.” – Alan Weintraut

What Is the Purpose of an Editorial?

The purpose of an editorial is to share a perspective, persuade others of your point of view, and possibly propose a solution to a problem.

The most important part is to pick one purpose and stick to it.

Rambling, incoherent editorials won’t do. They won’t get you the results or the response you might want.

When it comes to purpose, you want:

- Singular focus

- Personal connection

The first two probably make sense with no explanation. That last one (personal connection) deserves more attention.

The best editorials arise from personal passions, values, and concerns. You will naturally write with vigor and voice. Your emotion will find its way into your words.

Every bit of this will make your editorials instantly more compelling.

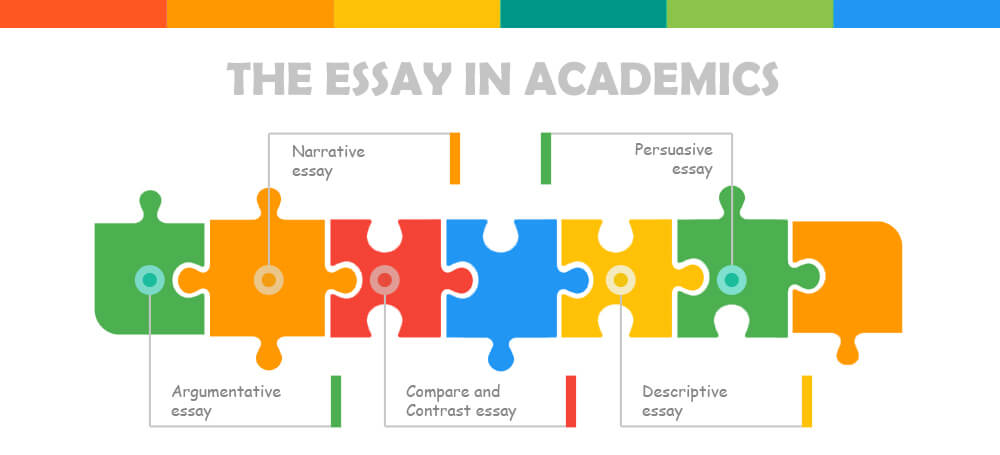

What Are the Different Types of Editorials?

There are two main types of editorials and a number of different subtypes.

One of the first steps in how to write an editorial is choosing the right type for your intended purpose or desired outcome.

The two main types of editorials:

Opinion Editorial

In an opinion editorial, the author shares a personal opinion about a local or national issue.

The issue can be anything from local regulations to national human trafficking.

Typically, the topic of an editorial is related to the topics covered in the publication. Some publications, like newspapers, cover many topics.

Solution Editorial

In a solution editorial, the author offers a solution to a local or national problem.

It’s often recommended for the author of solution editorials to cite credible sources as evidence for the validity of the proposed solution (BTW, research is also important for opinion editorials).

There are also several editorial subtypes based on purpose:

- Explain (you can explain a person, place, or thing)

- Criticism (you can critically examine a person, place, or thing)

- Praise (celebrate a person, place, or thing)

- Defend (you can defend a person, place, or thing)

- Endorsement (support a person, place, or thing)

- Catalyst (for conversation or change)

How To Write an Editorial (7 Easy Steps)

As a reminder, you can write an editorial by following seven simple steps.

- Choose a topic

- Choose a purpose

- Select an editorial type

- Gather research

- Write the editorial

- Write the headline

- Edit your editorial

If you want a short, visual explanation of how to write an editorial, check out this video from a bona fide New York Times Editor:

1) Choose a Newsworthy Topic

How do you choose a topic for your editorial?

You have several options. Your best bet is to go with a topic about which you feel strongly and that has broad appeal.

Consider these questions:

- What makes you angry?

- What makes your blood boil?

- What gets you excited?

- What is wrong with your community or the world?

When you write from a place of passion, you imbue your words with power. That’s how to write an editorial that resonates with readers.

2) Choose a Purpose

The next step for how to write an editorial is to choose your purpose.

What do you want to accomplish with your editorial? What ultimate outcome do you desire? Answering these questions will both focus your editorial and help you select the most effective editorial type.

Remember: a best practice is honing in on one specific purpose.

Your purpose might be:

- To trigger a specific action (such as voting)

- To raise awareness

- To change minds on an issue

3) Select a type

Now it’s time to select the best editorial type for your writing. Your type should align with your purpose.

In fact, your purpose probably tells you exactly what kind of editorial to write.

First, determine which major type of editorial best fits your purpose. You can do this by asking yourself, “Am I giving an opinion or offering a solution?”

Second, select your subtype. Again, look to your purpose. Do you want to explain? Persuade? Endorse? Defend?

Select one subtype and stick to it.

4) Gather Research

Don’t neglect this important step.

The research adds value, trust, credibility, and strength to your argument. Think of research as evidence. What kind of evidence do you need?

You might need:

- Research findings

All of these forms of evidence strengthen your argument.

Shoot for a mix of evidence that combines several different variations. For example, include an example, some statistics, and research findings.

What you want to avoid:

- Quote, quote, quote

- Story, story, story

Pro tip: you can find research articles related to your topic by going to Google Scholar.

For other evidence, try these sources:

- US Census Bureau

- US Government

- National Bureau of Economic Research

You might also want to check with your local librarian and community Chamber of Commerce for local information.

5) Write Your Editorial

Finally, you can start writing your editorial.

Aim to keep your editorial shorter than longer. However, there is no set length for an editorial.

For a more readable editorial, keep your words and sentences short. Use simple, clear language. Avoid slang, acronyms, or industry-specific language.

If you need to use specialized language, explain the words and terms to the reader.

The most common point of view in editorials is first person plural. In this point of view, you use the pronouns “we” and “us.”

When writing your editorial, it’s helpful to follow an Editorial Template. The best templates include all of the essential parts of an editorial.

Here is a basic Editorial template you can follow:

Introduction Response/Reaction Evidence Rebuttal Conclusion

Here is a brief breakdown of each part of an editorial:

Introduction: The introduction is the first part of an editorial. It is where the author introduces the topic that they will be discussing. In an editorial, the author typically responds to a current event or issue.

Response/Reaction: The response/reaction is the part of the editorial where the author gives their opinion on the topic. They state their position and give reasons for why they believe what they do.

Evidence: The evidence is typically a series of facts or examples that support the author’s position. These can be statistics, quotations from experts, or personal experiences.

Rebuttal: The rebuttal is the part of the editorial where the author addresses any arguments or counter-arguments that may be raised against their position. They refute these arguments and offer additional evidence to support their point of view.

Conclusion: The conclusion is the last part of an editorial. It wraps up the author’s argument and provides a final statement on the topic.

6) Write The Headline

Your headline must be catchy, not clickbait. There’s a fine line between the two, and it’s not always a clear line.

Characteristics of a catchy headline:

- Makes the reader curious

- Includes at least one strong emotion

- Clearly reveals the subject of the editorial

- Short and sweet

- Doesn’t overpromise or mislead (no clickbait)

Your headline will either grab a reader’s attention or it will not. I suggest you spend some time thinking about your title. It’s that important. You can also learn how to write headlines from experts.

Use these real editorial headlines as a source of inspiration to come up with your own:

- We Came All This Way to Let Vaccines Go Bad in the Freezer?

- What’s the matter with Kansas?

- War to end all wars

- Still No Exit

- Zimbabwe’s Stolen Election

- Running out of time

- Charter Schools = Choices

Suggested read: How To Write an Autobiography

7) Edit Your Editorial

The final step is to edit and proofread your editorial.

You will want to check your editorial for typos, spelling, grammatical, and punctuation mistakes.

I suggest that you also review your piece for structure, tone, voice, and logical flaws.

Your editorial will be out in the public domain where any troll with a keyboard or smartphone (which, let’s be honest, is everyone) can respond to you.

If you’ve done your job, your editorial will strike a nerve.

You might as well assume that hordes of people might descend on your opinion piece to dissect every detail. So check your sources. Check the accuracy of dates, numbers, and figures in your piece.

Double-check the spelling of names and places. Make sure your links work.

Triple-check everything.

Editorial Structures and Outlines

As you learn how to write an editorial, you have many choices.

One choice is your selection of structure.

There are several editorial structures, outlines, and templates. Choose the one that best fits your topic, purpose, and editorial type.

Every editorial will have a beginning, middle, and end.

Here are a few specific structures you can use:

- Problem, Solution, Call to Action

- Story, Message, Call to Action

- Thesis, Evidence, Recommendation

- Your View, Opposing Views, Conclusion

How Do You Start an Editorial?

A common way to start an editorial is to state your point or perspective.

Here are a few other ways to start your editorial:

- The problem

- Startling statement

- Tell a story

- Your solution

Other than the headline, the beginning of your editorial is what will grab your reader.

If you want to write an editorial that gets read, then you must write a powerful opening.

How Do You End an Editorial?

You can end with a call-to-action, a thoughtful reflection, or a restatement of your message.

Keep in mind that the end of your editorial is what readers will most likely remember.

You want your ending to resonate, to charge your reader with emotion, evidence, and excitement to take action.

After all, you wrote the editorial to change something (minds, policies, approaches, etc.).

In a few sections (see below), you will learn a few simple templates that you can “steal” to help you end your editorial. Of course, you don’t have to use the templates.

They are just suggestions.

Often, the best way to conclude is to restate your main point.

What Makes a Good Editorial?

Even if you learn how to write an editorial, it doesn’t mean the editorial will automatically be good. You may be asking, What makes a good editorial ?

A good editorial is clear, concise, and compelling.

Therefore, the best editorials are thought out with a clear purpose and point of view. What you want to avoid is a rambling, journal-type essay. This will be both confusing and boring to the reader.

That’s the last thing you want.

Here are some other elements of a good editorial:

- Clear and vivid voice

- Interesting point of view

- Gives opposing points of view

- Backed up by credible sources

- Analyzes a situation

“A good editorial is contemporary without being populist.” —Ajai Singh and Shakuntala Singh

How Do You Know If You’ve Written a Good Editorial?

Many people want to know how to tell if they have written a good editorial.

How do you know?

You can tell by the response you get from the readers. A good editorial sparks a community conversation. A good editorial might also result in some type of action based on the solution you propose.

An article by Ajai Singh and Shakuntala Singh in Mens Sana Monograph says this about good editorials:

It tackles recent events and issues, and attempts to formulate viewpoints based on an objective analysis of happenings and conflicting/contrary opinions. Hence a hard-hitting editorial is as legitimate as a balanced equipoise that reconciles apparently conflicting positions and controversial posturings, whether amongst politicians (in news papers), or amongst researchers (in academic journals).

Note that newsworthy events, controversy, and balance matter in editorials.

It’s also a best practice to include contradicting opinions in your piece. This lends credibility and even more balance to your peice.

Editorial Examples & Templates

As you write your own editorial, study the following example templates “stolen” from real editorials.

You can use these templates as “sentence starters” to inspire you to write your own completely original sentences.

Phrases for the beginning:

- It’s been two weeks since…

- Look no further than…

- The country can’t…

Phrases for the middle:

- That’s an astonishing failure

- It should never have come to this

- Other [counties, states, countries, etc.] are…

- Within a few days…

- Not everyone shares my [opinion, pessimism, optimism]

- Officials say…

Phrases for the end:

- Let’s commit to…

- Finally…

- If we can…we will…

Honestly, the best way to learn how to write an editorial is to read and study as many published editorials as possible. The more you study, the better you will understand what works.

Study more editorials at these links:

- New York Times editorials

- USA Today editorials

- The Washington Post

How To Write an Editorial for Students

Writing an editorial for students is virtually the same as writing an editorial at any other time.

However, your teacher or professor might give you specific instructions, guidelines, and restrictions. You’ll want to read all of these thoroughly, get clarity, and follow the “rules” as much as possible.

Writing an editorial is a skill that will come in handy throughout your life. Whether you’re writing a letter to the editor of your local paper or creating a post for your blog, being able to communicate your ideas clearly and persuasively is an important skill. Here are some tips to help you write an effective editorial:

- Know your audience. Who are you writing for? What are their concerns and interests? Keep this in mind as you craft your message.

- Make a clear argument. What is it that you want your readers to know? What do you want them to do? Be sure to state your case clearly and concisely.

- Support your argument with evidence. Use facts, statistics, and expert opinions to make your case.

- Use strong language . Choose words that will resonate with your readers and make them want to take action.

- Be persuasive, not blasting. You want your readers to be convinced by your argument, not turned off by aggressive language. Stay calm and collected as you make your case.

By following these tips, you can write an effective student editorial that will get results.

What Is an Editorial In a Newspaper?

The editorial section of a newspaper is where the publication’s editorial board weighs in on important issues facing the community. This section also includes columns from guest writers and staff members, as well as letters to the editor.

The editorial board is made up of the publication’s top editors, who are responsible for setting the tone and direction of the paper.

In addition to op-eds, the editorial section also features editorials, which are written by the editorial board and represent the official position of the paper on an issue.

While editorial boards may lean one way or another politically, they strive to present both sides of every issue in a fair and unbiased way.

Ultimately, the goal of the editorial section is to promote thoughtful discussion and debate on the topics that matter most to readers.

Tools for Writing an Editorial

If you want some extra help in writing an editorial, try these tools:

| AI Tools | Learn More |

|---|---|

Final Thoughts: How To Write an Editorial

Whew , we have covered a lot of ground in this article. I hope that you have gained everything you need to know about how to write an editorial.

There are a lot of details that go into writing a good editorial.

If you get confused or overwhelmed, know that you are not alone. Know that many other writers have been there before, and have struggled with the same challenges.

Mostly, know that you got this .

Related posts:

- How To Write an Ode (7 Easy Steps & Examples)

- Jasper Commands Template: Ultimate Guide + 300 Commands

- Best AI Essay Writer (With Examples)

- The Best Writing Books for Beginners

- How to Write a Topic Sentence (30+ Tips & Examples)

National Institute of Health (On Editorials)

1 thought on “How To Write An Editorial (7 Easy Steps, Examples, & Guide)”

Pingback: How To Write a Manifesto: 20 Ultimate Game-Changing Tips - CHRISTOPHER KOKOSKI

Comments are closed.

CURATE YOUR FUTURE

My weekly newsletter “Financialicious” will help you do it.

In This Post

How to write an editorial, in 6 steps.

An editorial is an opinion-driven piece that brings awareness to current events or topics of importance. Here’s what to include.

Editorials assert an opinion or perspective using journalistic principles.

If you have a strong opinion about a topic, knowing how to write an editorial essay can help you land more media visibility and readership.

Editorial writing is when a columnist, journalist, or citizen submits an opinion-based article to a media outlet. A good editorial will be measured and fair; it will make a clear argument with an end goal to persuade readers, raise awareness on a particular issue, or both. Editorials give people a chance to present a supporting or opposing view on a topical issue, and they’re usually formatted as first-person essays.

Opinion editorials (Op-eds) can be a great way to land a byline or full article with a media publication. It can let you assert a stance more powerfully than you would in a quotation or interview.

Key Takeaways

- Also known as an opinion piece, an editorial asserts an author’s position, and often tackles recent events.

- Newspapers have allocated space for editorials from readers for years. The opinion-editorial section is sometimes abbreviated as “op-ed.”

- Editorials are written in first person, from the perspective of the writer, but they should still lean on credible sources.

- Readers should also know how the writer or organization reconciles apparently conflicting positions. True editorial coverage is earned, not purchased.

In this article, we’ll touch on what an editorial piece actually is, along with examples of editorial structure to help you organize your thoughts as you're brainstorming ideas.

What is Editorial Writing?

Every strong editorial has, at its core, a thought-provoking statement or call to action. Editorial writers formulate viewpoints based on experience, supporting evidence, objective analysis, and/or opinion.

Editorials perform very well online. These days, readers don’t always want information alone. They also want interpretation or analysis, whether that be through a newspaper article, a thesis statement, a newsletter , or an opinionated news story. Editorials are powerful, but they are also often biased.

Here's an example of an editorial I wrote recently for Fortune Magazine . This section of Fortune is called Commentary, and it publishes one to two pieces a day from non-staff writers on a variety of business topics.

The specifics of this pitch are detailed in my “Pitching Publications 101” workshop.

Limited-Time Offer: ‘Pitching Publications 101’ Workshop

Get the ‘Pitching Publications 101’ Workshop and two other resources as part of the Camp Wordsmith® Sneak Peek Bundle , a small-bite preview of my company's flagship publishing program. Offer expires one hour from reveal.

Many media outlets rotate in opinion columnists to offer unique perspectives on a regular basis. Here’s a screenshot from The Washington Post opinion page ; the paper has over 80 opinion columnists, who write regularly about topics like policy, health, and climate change.

Large media publications usually have a separate section for opinion and commentary.

What Is an Editorial Board?

In contrast, you may have seen a newspaper or media publication release a statement from its editorial board. The editorial board consists of the publication’s editors, who together release a joint statement about a certain topic.

Examples of editorial topics include:

- An editorial board endorsing a local politician in a forthcoming election.

- Commentary on issues of local importance.

- Scientists announcing a newly published research paper that has mainstream relevance.

- Perspectives from citizens who come from various walks of life.

- Submitted opinion pieces in school newspapers or academic journals.

Good Examples of Published Editorials

The best way to get a feel for writing editorials is to see some effective editorial examples in action.

The Los Angeles Times and 70+ other newspapers condemned the actions of Scott Adams, the illustrator behind Dilbert cartoons. Since the cartoons were scheduled to run in the paper for a few more weeks, the editorial board released a statement updating readers on their decision to pull the cartoon, along with what next steps would be taken.

Many editorials are written by celebrities or public figures as a way to create awareness or touch on a controversial subject. Chrissy Teigen published an editorial on Medium about her miscarriage. Medium is an open-source publishing platform that many personalities use to make independent op-ed statements publicly.

A peer of mine, Zach McKenzie, wrote an editorial on the lack of sober queer spaces in Houston, America’s fourth-largest city. He pitched it to the Houston Chronicle, and an editor accepted and published his opinion piece.

He later became a freelance writer for the paper. Since you'll often work with an editor on your editorial, this could open doors for freelance opportunities.

Editorials can also refute other editorials. These are sometimes formatted as letters to the editor instead. In 2011, Martin Lindstrom published an op-ed with The New York Times entitled “You Love Your iPhone. Literally” , which asserted that neuroimaging showed we feel human love for our smartphones. A response letter signed by a total of 45 neuroscientists was sent to the Times condemning the op-ed as scientifically inaccurate.

Types of Editorials

Editorials typically fall into one of four categories: explanation, criticism, persuasive essay, or praise.

No. 1: Explanation or Interpretation

Not all editorials have to be about controversial topics. Editorials written by a board or an organization might simply summarize main points of new research or a recent decision.

No. 2: Criticism

Criticism is by far the most popular type of editorial, because, well, we love the drama! 🍿

Opinion editorial usually disagrees with the status quo on a given topic, but does so in a well-researched way. An opinion editor will do more than simply fix grammatical errors; they often guide the contributor through the writing process and reinforce good editorial style.

No. 3: Persuasive Essay

Technically, an editorial can also simply be a persuasive essay, written in first person. As long as the main point has a good chance at catching a reader’s attention, editors will be interested in the piece.

No. 4: Praise

Sometimes, an opinion piece actually agrees with the status quo or current news angle, although these pieces are less common.

How to Write an Editorial in 6 Steps

- Pick a topic that has mainstream appeal.

- Lead with a summary of your opinion.

- State the facts.

- Summarize the opposition’s position.

- Refute the opposition.

- Offer readers a solution or reframe.

Step 1: Pick a Topic That Has Mainstream Appeal

If you want your essay to be published in a news outlet, it has to be, well, news!

Connect your thesis statement to a current event. Your topic should be one that the majority of the public can understand or relate with. Remember: Business is niche, media is broad. Make it mainstream.

Step 2: Lead With a Summary of Your Opinion

Editorial format usually opens with a summary of your thesis statement and/or new ideas in the first paragraph. In journalism, this section is known as the lede —part of the “inverted pyramid” writing process —and it’s the most important section of your article.

Remember, if readers can’t get oriented and understand your own opinion within the first few sentences, they’ll leave.

Related: How to Write a News Lead

Step 3: State the Facts

One detail any writers miss regarding how to write an editorial is giving sufficient background information. In some ways, you have to operate like a journalist when you begin writing editorials. Collect facts and outline the main points for your reader so they grasp the issue at hand.

Step 4: Summarize the Opposition’s Position

Good editorial presents both sides of the story. Even though this is an opinion-based essay, you want your editorial format to acknowledge common counter arguments.

Step 5: Refute the Opposition

This is the fun part! Use logic and evidence in your writing to reinforce your point. When you cite sources and statistics, your writing will pack more punch.

Step 6: Offer Readers a Solution or Reframe

Lastly, go into a clear conclusion and possible solutions. Don’t just dump an opinion on your reader and then leave them with nothing to do or consider. You’ve persuaded us with a hard-hitting editorial on a topic you feel strongly about—now ask us to do something!

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes a good editorial.

A good editorial will assert a clear and compelling point. The editorial should cite reputable sources in order to form its point, and should address why the opposing viewpoint is misguided.

What Is the Purpose of an Editorial?

An editorial provides contrast to day-to-day journalism with perspectives and commentary on recent events. Editorials are not objective; they are subjective and opinionated by design.

What Are Examples of Editorial Content?

An editorial could be a column in a magazine or newspaper, a public statement, a newsletter, or even a blog post. A letter to the editor is usually not considered an editorial.

Write Your First (or Next) Editorial This Year

You don’t have to be a journalist to pitch and write editorials, but you do have to have a point of view that will capture a reader’s attention. Study the writing process of editorials and you’ll have a better shot at getting your opinions published. ⬥

Thanks For Reading 🙏🏼

Keep up the momentum with one or more of these next steps:

📣 Share this post with your network or a friend. Sharing helps spread the word, and posts are formatted to be both easy to read and easy to curate – you'll look savvy and informed.

📲 Hang out with me on another platform. I'm active on Medium, Instagram, and LinkedIn – if you're on any of those, say hello.

📬 Sign up for my free email list. This is where my best, most exclusive and most valuable content gets published. Use any of the signup boxes on the site.

🏕 Up your writing game: Camp Wordsmith is a free online resources portal all about writing and media. Get instant access to resources and templates guaranteed to make your marketing hustle faster, better, easier, and more fun. Sign up for free here.

📊 Hire me for consulting. I provide 1-on-1 consultations through my company, Hefty Media Group. We're a certified diversity supplier with the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce. Learn more here.

Welcome to the blog. Nick Wolny is a writer, editor and consultant based in Los Angeles.

- Academic Writing Guides

A Beginner’s Guide on How to Write an Editorial

Writing an editorial essay lets you share your viewpoint on or advocate for a particular cause with your audience. A great editorial article creates awareness on a matter and influences people’s positions on it. But how do you compose such an article?

This post shares valuable insights on how to write an editorial that impresses editors and influences readers. Keep reading to enhance your effectiveness and master how to write an editorial essay .

What Is an Editorial Paper?

Let’s start by answering the big question, “ What is an editorial paper ?” As the name suggests, an editorial article or paper expresses an editor’s stand on a matter and explains the issue at hand. However, it doesn’t mean that the editor exclusively expresses their thoughts. That’s why the writer must research the topic and include other people’s ideas on the subject.

A great editorial paper focuses on a given topic. The author must focus on why their target readers care about the topic and why some people might hold contrary views. That’s why understanding the two sides of a matter makes an editorial more interesting and acceptable to many audiences. You will also need to present readers with valid evidence that supports your opinions.

When your editorial addresses a problem, you must also present clear solutions. Tell your readers what should be done to address the situation. If necessary, speak to the relevant authorities that need to take appropriate measures to address particular situations. For instance, you can address the government or institutions that can midwife solutions.

How to Write an Editorial

The rise of social media has provided more people with a free platform to express their platforms. Consequently, people are no longer sure of what it takes to write editorials . However, it doesn’t mean that you can master how to write an editorial that impresses editors. This section shares insights to help you compose a great editorial that speaks to your constituents.

Choose an Attention-Grabbing Topic

Start your journey by selecting an interesting topic with current news value and serves a defined goal. At times, handling a controversial topic can attract people.

Research and Gather Facts

Next, gather the facts surrounding your topic before presenting it to your readers. You must research the facts so that your opinion isn’t based on your feelings. Use credible sources and collect the latest facts surrounding your topic.

Drafting the Editorial

Draft your paper to be short and clear, at least 600 to 800 words. Additionally, avoid using jargon.

- Introduction. Make its intro as attractive as possible. You can open it with relevant stats, a quote from a famous person your readers respect, or a thought-provoking question.

- Body. The body should address all the details surrounding your topic. It should follow the 5 W’s and H pattern (what, when, where, who, why, and how). This section should address opposition and provide evidence to support your stance. When addressing problems, propose valid and practical solutions.

- Conclusion. End your editorial with a strong, thought-provoking statement. Give your readers a sense of closure and completeness from this section.

Proofread and Edit

Polish your editorial by editing and proofing it for styling, grammar, and spelling perfection before submitting it.

Tips for Writing a Good Editorial

Do you want to master how to write an editorial article ? Below are tips to help you up your editorial writing game.

- Be decisive. A great editorial takes a firm position on a matter. Whenever you mention a contrary position, you immediately show readers why it’s inaccurate and why readers should agree with your stand.

- Provide fresh ideas. Research your topic well to provide readers with fresh ideas. Whereas people have ideas on specific issues, adding a fresh angle to them makes your article more valuable.

- Offer solutions. If you address a problem, your article should provide possible solutions. Don’t just describe problems for which you can’t prescribe solutions.

- Focus on your interests. Whenever possible, select a topic you are passionate about to be better placed to address an issue you care about. Do you care about quality education? Then don’t write on maternal health.

Types of Editorials

It’s essential to understand the types of editorials before you write an editorial for a chosen publication. We have four types of editorials, categorized based on their tone and purpose. These categories are:

- Explaining and Interpreting: These editorials let editors explain how they handle sensitive and controversial topics.

- Criticizing: Such editorials focus on the problem rather than the solution. They criticize actions, decisions, or particular situations.

- Persuading: These editorials propose solutions and convince readers to take appropriate actions towards a matter.

- Praising: Such editorials show support for and commend notable actions by organizations or individuals.

How Do Publications Choose Editorials?

So, how do newspapers and other publications choose an editorial for students ? Most major publications employ op-ed columnists to provide a given number of published editorials in a given year. Some college and high school newspapers have their own columnists who regularly provide editorial content. Most of these publications also solicit guest editorials from external sources. These editorials are like letters to editors but still receive a more generous word count.

The editors use their discretion to accept or reject some editorials. For instance, if they think an editorial touches a needlessly controversial subject or exposes the publication to legal implications, they reject it. In other cases, an editorial board may send the article to the writer to revise or streamline it before resubmitting it for publication.

Editorial Example

Whenever you are stuck on how to write an editorial,l examples will be of much help. This section contains an example regarding the educational system to inspire your writing.

A Critical Editorial Example: A Clarion Call to Reform a Flawed Education System

Our education system is flawed and outdated in many areas and needs urgent reforms. It has many outdated teaching methods that don’t fully engage students. For instance, rote learning stifles innovation and critical thinking, leaving learners ill-equipped when they enter the real world.

Class sizes are still too large, hindering personalized learner attention. Overworked instructors struggle to address student needs. The obsession with standardized testing emphasizes memorization over creative learning. Consequently, it stresses learners and undermines the joy of learning.

Further, the system is unequal. For example, wealthier districts receive more funding, while underprivileged schools lack basic resources. This inequality perpetuates a vicious cycle of disadvantage and limits opportunities for many underprivileged learners.

Thus, everyone must demand radical and immediate reforms. We must all demand innovative teaching methods, smaller class sizes, and equal funding to transform the education landscape. Let’s call for reforms and create an education system that empowers our children, into whose hands we’ll leave our nation.

Editorial Essay Topics

Mastering how to write an editorial paper requires you to choose appropriate topics. To help you do that, we have selected hot sample topics for editorial essay projects. Check them out to jumpstart your next assignment.

- The role of junk food in increasing obesity.

- Is PlayStation turning our children into zombies?

- The dark side of social media.

- Should governments legalize recreational marijuana?

- How does recycling promote a clean and healthy environment?

- The dark side of the selfie culture.

- Are e-cigarettes any safer than traditional ones?

Conclusion

There, you have everything you need to compose an editorial article that impresses readers and fetches good grades. We hope you will use all the valuable information this post shared on how to write an editorial to up your game.

- Essay Writing Guides

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of editorial

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of editorial (Entry 2 of 2)

Examples of editorial in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'editorial.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

1744, in the meaning defined at sense 1

1825, in the meaning defined above

Articles Related to editorial

Words We're Watching: 'Editorial'

A new look for an old word

Dictionary Entries Near editorial

editorialist

Cite this Entry

“Editorial.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/editorial. Accessed 7 Jul. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of editorial.

Kids Definition of editorial (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on editorial

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for editorial

Nglish: Translation of editorial for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of editorial for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, flower etymologies for your spring garden, 12 star wars words, 'swash', 'praya', and 12 more beachy words, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, games & quizzes.

How to Write an Editorial?

- Open Access

- First Online: 24 October 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Samiran Nundy 4 ,

- Atul Kakar 5 &

- Zulfiqar A. Bhutta 6

46k Accesses

11 Altmetric

An Editorial is defined as an opinion or a view of a member of the editorial board or any senior or reputed faculty written in a journal or newspaper. The statement reflects the opinion of the journal and is considered to be an option maker. If you have been asked to write an editorial it means that you are an expert on that topic. Editorials are generally solicited.

Editorial writers enter after battle and shoot the wounded Neil Goldschmidt, American Businessman and Politician (1940–…)

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The Journal Editor as Academic Custodian

Authors Versus Editors: A Personal View on Dealing with How Long a Book to Write or Publish

1 what is an editorial, 2 how is the topic for an editorial chosen.

This is decided by the members of the editorial board and is usually related to important work which is about to be published in the journal. If you are invited to write an editorial on a topic of your choosing you should preferably write one on a general or public health problem that might interest a wide readership [ 1 ].

3 What Should be the Contents of an Editorial?

It has been said that ‘Editors, by and large, are reticent people, with a magnified sense of their own importance. Well, this may hurt some, but before they jump at our throats, let us clarify that we belong there as well’. The editorial should not look like an introduction to an original article or a self-glorifying piece of fiction.

Editorial writing has been compared to a double-edged sword, you can be apolitical and pragmatic but at the same time dogmatic in your views. The majority of editorials provide the readers a balanced view of the problems raised in a particular research paper and place them in a wider context. But there is no harm in going to extremes if the data supports your view. However, you should not mock the paper’s authors [ 2 ].

4 What Is the Basic Information Required for Writing an Editorial?

First, read the paper for which the editorial has been asked again and again. Do a literature search and critically analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the study. Read about how and why other authors came to similar or different conclusions. Discuss whether or not the findings are important [ 3 ].

An editorial should be brief, about one to two pages long, but it should be powerful. The language should be a combination of good English and good science. The writing can be ‘embellished by language but not drowned in it’. While a good editorial states a view, it does not force the reader to believe it and gives him the liberty to form his own opinion.

5 What Are the Steps Involved in Writing an Editorial?

Choose a topic intelligently.

Have a catchy title.

Declare your stance early.

Build up your argument with data, statistics and quotes from famous persons.

Provide possible solutions to the problem.

Follow a definite structure consisting of an introduction, a body that contains arguments and an end with a tailpiece of a clear conclusion. It should give the reader a chance to ponder over the questions and concerns raised.

6 What Are the Types of Editorial?

Editorials can be classified into four types. They may:

Explain or interpret : Editors use this type of editorial to explain a new policy, a new norm or a new finding.

Criticize: this type of editorial is used to disapprove of any finding or observation.

Persuade: These encourage the reader to adopt new thoughts or ideas.

Praise: These editorials admire the authors for doing something well.

7 What Is the Purpose of an Editorial?

An editorial is a personal message from the editor to the readers. It may be a commentary on a published article or topic of current interest which has not been covered by the journal. Editorials are also written on new developments in medicine. They may also cover non-scientific topics like health policy, law and medicine, violence against doctors, climate change and its effect on health, re-emerging infectious diseases, public interventions for the control of non -communicable diseases and ongoing epidemics or pandemics [ 4 ].

8 What Are the Instructions for Writing Editorials in Major Journals?

Many editorials written by in-house editors or their teams represent the voice of the journal. A few journals allow outside authors to write editorials. The details for these suggested by some of the leading journals are given in Table 26.1 .

9 What Is a Viewpoint?

A Viewpoint is a short article that focuses on some key issues, cutting-edge technology or burning topics or any new developments in the field of medicine. It can be a ‘personal opinion’ or any piece of information, which gives the author’s perspective on a particular issue, supported by the literature. Viewpoints can also be unencumbered by journal policy. The normal length of viewpoints can flexible. The BMJ, for instance, also allows viewpoints to be written by patients.

Viewpoints may share a few common features with commentaries, perspectives and a focus which is a brief, timely piece of information. It is like a ‘spotlight’ that contains information on research funding, policy issues and regulatory issues whereas a commentary is an in-depth analysis of a current matter which can also include educational policy, law besides any other seminal issue.

10 Conclusions

An editorial is written to provide a crisp, concise overview of an original article. It is generally deemed to be an honour to be asked to write an editorial.

One needs to follow the general instructions for writing editorials for a particular journal.

It should have an objective and the flow of ideas should be clear.

Squires BP. Editorials and platform articles: what editors want from authors and peer reviewers. CMAJ. 1989;141:666–7.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Singh A, Singh S. What is a good editorial? Mens Sana Monogr. 2006;4:14–7.

Article Google Scholar

Cleary M, Happell B, Jackson D, Walter G. Writing a quality editorial. Nurse Author & Editor. 2012;22:3.

Article types at The BMJ. Last accessed on 12th July 2020. Available on https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors/article-types

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Liver Transplantation, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Samiran Nundy

Department of Internal Medicine, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

Institute for Global Health and Development, The Aga Khan University, South Central Asia, East Africa and United Kingdom, Karachi, Pakistan

Zulfiqar A. Bhutta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Nundy, S., Kakar, A., Bhutta, Z.A. (2022). How to Write an Editorial?. In: How to Practice Academic Medicine and Publish from Developing Countries?. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5248-6_26

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5248-6_26

Published : 24 October 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-5247-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-5248-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- How it works

- Top Writers

- TOP Writers

A guide to writing a persuasive Newspaper Editorial Essay

Editorial essay definition.

To understand and personally define an editorial, you should first try to define the word “editorial.” It is a newspaper article that covers the diverse concepts of the author. The author may choose to write about any topic, but it should focus on social issues concerning the subject matter. Each point expressed should be backed up with reliable support evidence or facts to give meaning to your work.

Detailed research should be done to identify a suitable topic for discussion. An editorial essay should highlight and discuss the problem identified, and at the end offer reliable solutions. For example, if you as the author plan to address issues that are related to the mentally handicapped population, you should give detailed feedback about ways to tackle such an issue for a suitable solution. You should develop a message that addresses those affected with this issue, with part of the message sent to the healthcare providers on how to handle the situation.

A newspaper editorial essay also addresses the ruling government on the issue at hand and the need for them to take necessary actions. Writing an editorial essay is similar to writing a research or a normal essay paper. If you know this, then writing your piece will be easy and the work with come out interesting to the reader in the long run.

Ways of writing Different Editorial Essays

Editorial essays are quite different from other types of essays. They are clustered according to the purpose they serve, unlike other essays where they are categorized according to their nature.

With the above information, it’s safe to say that there is no single way of answering what an editorial essay is, without gaining knowledge of all the types of editorial essays. There are several ways of writing your essay. You could:

- Define/Expound/Interpret the Subject

While writing your newspaper article, highlight how it addresses a specific subject. For instance, as an editor of a fashion company’s magazine, you could address the different fashion trends on the rise to your readers.

- Criticize the Problem

Critical thinking is needed by all writers to come up with a meaningful and interesting piece which addresses a vital issue. Bear in mind that an excellent editorial essay provides a critique on cases in question which provide solutions to existing problems. This craft is intended to make the reader identify the problem and not just the solutions offered.

- Use the Central Argument Focus of the Editorial to Convince your Audience

You should inspire your readers to implement solutions by getting involved in the action from the introduction of your essay. While editorial essays only offer critique, persuasive papers handle all the suggested solutions without paying attention or providing information about the problem.

Editorials relating to this theme focus on praising and admiring the works of organizations or people involved in a beneficial activity to society. While writing these types of essays, remember to place your focus on highlighting the positive outcome and appreciation of the subjects involved.

If by now you are still not fully satisfied with the information given about editorial essays, no need to worry. Below Tutoriage experts have introduced and explained other ways that can help you to craft a first-class editorial essay.

More Ways to Ensure You Always Write a Persuasive and Attractive Editorial Essay

Social media is the reason for the fierce writing we all experience in this time and age. For that reason, many people cannot craft a creative piece for a persuasive newspaper editorial. However, this should not be a problem as we have provided more vital tips and advice on how to be a professional writer of an editorial essay.

- Look for controversial problems: -the use of this theme provides a debatable discussion which will engage your readers. Since the use of this theme provides room for research, ask your audience questions as you gain more perspective of the subject in question.

- Making the right decision is important in writing a persuasive editorial essay: -the author can only support one side of a controversial paper. Before you start writing one, choose a side you feel best fit for you and you can back up with your experience and knowledge about it.

- Read a famous newspaper from your state: -reading this type of newspapers is helpful in many ways. They contain the relevant topics that need to be addressed while providing facts and solutions to the issues addressed. As they lay down their opinion, they leave the final judgment in the hands of public opinion.

- There are many ways to explain solutions in an editorial essay: -it is important for you to provide your audience with multiple solutions for them to make their own preferred individual choices.

An inspirational excerpt by Minyvonne Burke from the United States’ Daily News says that: –

“For an argument to make sense, make sure you talk about a couple of analogies. You are entitled to choose diverse social, cultural and political analogies as many people place trust in such areas. For instance, your research problem could be about the rising suspicion of the integrity of the several mobile spying applications in the market.” Burke adds that “search for relating issues in other technologically advanced countries whose family adopt this type of security to ensure the safety of their families. When it comes to writing an editorial, you’re searching for solutions as you realize what other places did to resolve their issues.”

Steps of Writing a Newspaper Editorial

There are several features for writing an editorial essay you will require as an editor to know and have them at the back of your mind.

- An impressing and engaging introduction, which will be accompanied by the body paragraphs and a compelling solution. You will realize that the structure is similar to many other essay types.

- Your interpretation of the issue-at-hand should make sense, through the use of factual or statistical evidence. At this point, have in mind that the complex issues should get more attention.

- Find the most effective news angle and use it appropriately.

- You need to know that the arguments brought forward by the opposing group are totally impartial and objective.

- While you write an editorial essay, make sure that you put across your different perspectives on the topic of discussion and do it in the most formal language.

- Utilize professionalism and criticism while crafting solutions.

- Don’t forget to put down a summary and a persuasive call for action.

Ensure that you read the instructor’s guidelines before you start writing your persuasive essay. Consider factors that you need to develop your work such as the content, formatting and the number of words you are limited to.

Topics for Editorial Essays

Below are some of the best essay subjects you can use to create your own. Additionally, you will find appealing research issues and their respective solutions.

- For Charter Institutions, driving to the right decision is paramoun t

For example: – “Public charter schools are associated with the public schooling program, which sticks to the required standards of learning. These types of institutions should demonstrate high levels of efficiency in all their adopted teaching methods. Any school which does not stick to these aspects should be closed if they do not uphold the required standards. The teachers have the mandate to educated heir students according to the standards set by the United States of America learning system.”

- Reality alternation and development by reality television programs

Example: – “Reality shows aired on television mislead people into losing touch with the reality. Most of the directors try to convince the audience that the problems faced by their characters are the same we face in our day to day lives. They even try to convince the viewers that the consequences face by their characters is far more adverse than those faced in reality. Research conducted by Michigan State University by Dr. Gibson states that long term viewing of such programs brings about specific challenges. One of the challenges is heightened levels of aggression within the people living in the United States. The viewer rating of such programs should be placed at an age that will prevent the adolescent age group from viewing them.”

Other topic designs include:

- Advantages of higher education in the United States.

- Understanding the reasons and consequences of the Subprime crisis.

- Is legalization of marijuana a good move for its soothing effects, or destructive to the brain

- What challenges are likely to be faced with the banning of cigarettes

- A recap of the NBA season: Primary goals, training, prospect, prediction, best-performing players, debate and outcomes.

- Facts proving that gambling is illegal

- The best treatment available for diabetes

- Why is the death penalty legal in my country?

More example samples of persuasive editorial essay topics can be found in the academic writing websites. To create an editorial essay that is captivating and has a logical flow of ideas, you need to adopt a structure that will formulate the backbone of your work.

An Approach You Should Use in Writing a Persuasive Editorial Essay

Identify and pick the preferred topic.

Go ahead and select a debatable social issue and address it from all possible perspectives. Always remember to address a social issue that your target audience will be willing to read through to the end. Brainstorm on the ideas you have and choose one specific topic you are familiar with and can tackle with creativity and accuracy.

Offering Your Opinion

You should be aware that writing an editorial is the same as crafting an argumentative essay. At this point select a debatable, contradictive, and recently discoursed issue, and highlight your stance about it using valid evidence. An excellent tutorial should have both the positive and negative aspects concerning the topic of discussion. As you highlight your stand on the mater, remember not to pay attention to only one side. Looking for professional and editorial services are acceptable in instances you experience difficulty in handling the topic of discussion and writing the essay.

Putting Down the Outline

Having a framework for your editorial essay is vital in ensuring your work is well arranged, with the existence of a logical flow of ideas to make the essay legible and with high levels of professionalism. It is crucial because it helps you not to go off topic and keep to the subject of discussion when as new ideas pop up in the writing process. Your concepts will be well organized and structured to perfection.

Composing the Final Piece of Editorial

First, come up with an argument that is related to your selected topic and craft a headline that will attract the attention of your readers and impress them to read it some more. For instance, including an exclamation mark is a sure way for compelling your readers to look through your work. Use of rhetorical questions is also a way that will engage the reader. For each argument presented, make sure that you support them with valid resources, factual data, and examples. An effective way to achieve this is by highlighting the positive and negative aspects of issues addressed.

Here are some extra pointers to help you in your creation of a persuasive editorial essay: –

- Assimilating facts and figures from reliable online resources or those that are available in the library can be of great help. The resources will be of help in the explanation of your argument to make it credible and concrete.

- The most interesting evidence should be the last to be discussed. By doing this, you can keep your reader hooked to the essay and willing to read it all through.

- Don’t be too passive in the ideas that are not major. Engage your readers and address each point of view clearly and with necessary support offered to make sense out of it.

Conclusion or Relatable Solutions

The edited piece of your work should have a concrete solution that is founded on constructive criticism. You should still remember you have two perspectives about your issue of concern. For example, if you’re covering the government’s effort to reduce the use of tobacco by applying regulations and rules to govern its use, identify and discuss why this strategy is effective and vital as compared to any other. Also, remember to propose any alternative regulations that can be effective in achieving the desired goal.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

What Is Academic Writing? | Dos and Don’ts for Students

Academic writing is a formal style of writing used in universities and scholarly publications. You’ll encounter it in journal articles and books on academic topics, and you’ll be expected to write your essays , research papers , and dissertation in academic style.

Academic writing follows the same writing process as other types of texts, but it has specific conventions in terms of content, structure and style.

| Academic writing is… | Academic writing is not… |

|---|---|

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Types of academic writing, academic writing is…, academic writing is not…, useful tools for academic writing, academic writing checklist.

Academics mostly write texts intended for publication, such as journal articles, reports, books, and chapters in edited collections. For students, the most common types of academic writing assignments are listed below.

| Type of academic text | Definition |

|---|---|

| A fairly short, self-contained argument, often using sources from a class in response to a question provided by an instructor. | |

| A more in-depth investigation based on independent research, often in response to a question chosen by the student. | |

| The large final research project undertaken at the end of a degree, usually on a of the student’s choice. | |

| An outline of a potential topic and plan for a future dissertation or research project. | |

| A critical synthesis of existing research on a topic, usually written in order to inform the approach of a new piece of research. | |

| A write-up of the aims, methods, results, and conclusions of a lab experiment. | |

| A list of source references with a short description or evaluation of each source. |

Different fields of study have different priorities in terms of the writing they produce. For example, in scientific writing it’s crucial to clearly and accurately report methods and results; in the humanities, the focus is on constructing convincing arguments through the use of textual evidence. However, most academic writing shares certain key principles intended to help convey information as effectively as possible.

Whether your goal is to pass your degree, apply to graduate school , or build an academic career, effective writing is an essential skill.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Formal and unbiased

Academic writing aims to convey information in an impartial way. The goal is to base arguments on the evidence under consideration, not the author’s preconceptions. All claims should be supported with relevant evidence, not just asserted.

To avoid bias, it’s important to represent the work of other researchers and the results of your own research fairly and accurately. This means clearly outlining your methodology and being honest about the limitations of your research.

The formal style used in academic writing ensures that research is presented consistently across different texts, so that studies can be objectively assessed and compared with other research.

Because of this, it’s important to strike the right tone with your language choices. Avoid informal language , including slang, contractions , clichés, and conversational phrases:

- Also , a lot of the findings are a little unreliable.

- Moreover , many of the findings are somewhat unreliable.

Clear and precise

It’s important to use clear and precise language to ensure that your reader knows exactly what you mean. This means being as specific as possible and avoiding vague language :

- People have been interested in this thing for a long time .

- Researchers have been interested in this phenomenon for at least 10 years .

Avoid hedging your claims with words like “perhaps,” as this can give the impression that you lack confidence in your arguments. Reflect on your word choice to ensure it accurately and directly conveys your meaning:

- This could perhaps suggest that…

- This suggests that…

Specialist language or jargon is common and often necessary in academic writing, which generally targets an audience of other academics in related fields.

However, jargon should be used to make your writing more concise and accurate, not to make it more complicated. A specialist term should be used when:

- It conveys information more precisely than a comparable non-specialist term.

- Your reader is likely to be familiar with the term.

- The term is commonly used by other researchers in your field.

The best way to familiarize yourself with the kind of jargon used in your field is to read papers by other researchers and pay attention to their language.

Focused and well structured

An academic text is not just a collection of ideas about a topic—it needs to have a clear purpose. Start with a relevant research question or thesis statement , and use it to develop a focused argument. Only include information that is relevant to your overall purpose.

A coherent structure is crucial to organize your ideas. Pay attention to structure at three levels: the structure of the whole text, paragraph structure, and sentence structure.

| Overall structure | and a . . |

|---|---|

| Paragraph structure | when you move onto a new idea. at the start of each paragraph to indicate what it’s about, and make clear between paragraphs. |

| Sentence structure | to express the connections between different ideas within and between sentences. to avoid . |

Well sourced

Academic writing uses sources to support its claims. Sources are other texts (or media objects like photographs or films) that the author analyzes or uses as evidence. Many of your sources will be written by other academics; academic writing is collaborative and builds on previous research.

It’s important to consider which sources are credible and appropriate to use in academic writing. For example, citing Wikipedia is typically discouraged. Don’t rely on websites for information; instead, use academic databases and your university library to find credible sources.

You must always cite your sources in academic writing. This means acknowledging whenever you quote or paraphrase someone else’s work by including a citation in the text and a reference list at the end.

| In-text citation | Elsewhere, it has been argued that the method is “the best currently available” (Smith, 2019, p. 25). |

| Reference list | Smith, J. (2019). (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Norton. |

There are many different citation styles with different rules. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago . Make sure to consistently follow whatever style your institution requires. If you don’t cite correctly, you may get in trouble for plagiarism . A good plagiarism checker can help you catch any issues before it’s too late.

You can easily create accurate citations in APA or MLA style using our Citation Generators.

APA Citation Generator MLA Citation Generator

Correct and consistent

As well as following the rules of grammar, punctuation, and citation, it’s important to consistently apply stylistic conventions regarding:

- How to write numbers

- Introducing abbreviations

- Using verb tenses in different sections

- Capitalization of terms and headings

- Spelling and punctuation differences between UK and US English

In some cases there are several acceptable approaches that you can choose between—the most important thing is to apply the same rules consistently and to carefully proofread your text before you submit. If you don’t feel confident in your own proofreading abilities, you can get help from Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or Grammar Checker .

Academic writing generally tries to avoid being too personal. Information about the author may come in at some points—for example in the acknowledgements or in a personal reflection—but for the most part the text should focus on the research itself.

Always avoid addressing the reader directly with the second-person pronoun “you.” Use the impersonal pronoun “one” or an alternate phrasing instead for generalizations:

- As a teacher, you must treat your students fairly.

- As a teacher, one must treat one’s students fairly.

- Teachers must treat their students fairly.

The use of the first-person pronoun “I” used to be similarly discouraged in academic writing, but it is increasingly accepted in many fields. If you’re unsure whether to use the first person, pay attention to conventions in your field or ask your instructor.

When you refer to yourself, it should be for good reason. You can position yourself and describe what you did during the research, but avoid arbitrarily inserting your personal thoughts and feelings:

- In my opinion…

- I think that…

- I like/dislike…

- I conducted interviews with…

- I argue that…

- I hope to achieve…

Long-winded

Many students think their writing isn’t academic unless it’s over-complicated and long-winded. This isn’t a good approach—instead, aim to be as concise and direct as possible.

If a term can be cut or replaced with a more straightforward one without affecting your meaning, it should be. Avoid redundant phrasings in your text, and try replacing phrasal verbs with their one-word equivalents where possible:

- Interest in this phenomenon carried on in the year 2018 .

- Interest in this phenomenon continued in 2018 .

Repetition is a part of academic writing—for example, summarizing earlier information in the conclusion—but it’s important to avoid unnecessary repetition. Make sure that none of your sentences are repeating a point you’ve already made in different words.

Emotive and grandiose

An academic text is not the same thing as a literary, journalistic, or marketing text. Though you’re still trying to be persuasive, a lot of techniques from these styles are not appropriate in an academic context. Specifically, you should avoid appeals to emotion and inflated claims.

Though you may be writing about a topic that’s sensitive or important to you, the point of academic writing is to clearly communicate ideas, information, and arguments, not to inspire an emotional response. Avoid using emotive or subjective language :

- This horrible tragedy was obviously one of the worst catastrophes in construction history.

- The injury and mortality rates of this accident were among the highest in construction history.

Students are sometimes tempted to make the case for their topic with exaggerated , unsupported claims and flowery language. Stick to specific, grounded arguments that you can support with evidence, and don’t overstate your point:

- Charles Dickens is the greatest writer of the Victorian period, and his influence on all subsequent literature is enormous.

- Charles Dickens is one of the best-known writers of the Victorian period and has had a significant influence on the development of the English novel.

There are a a lot of writing tools that will make your writing process faster and easier. We’ll highlight three of them below.

Paraphrasing tool

AI writing tools like ChatGPT and a paraphrasing tool can help you rewrite text so that your ideas are clearer, you don’t repeat yourself, and your writing has a consistent tone.

They can also help you write more clearly about sources without having to quote them directly. Be warned, though: it’s still crucial to give credit to all sources in the right way to prevent plagiarism .

Grammar checker

Writing tools that scan your text for punctuation, spelling, and grammar mistakes. When it detects a mistake the grammar checke r will give instant feedback and suggest corrections. Helping you write clearly and avoid common mistakes .

You can use a summarizer if you want to condense text into its most important and useful ideas. With a summarizer tool, you can make it easier to understand complicated sources. You can also use the tool to make your research question clearer and summarize your main argument.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Use the checklist below to assess whether you have followed the rules of effective academic writing.

- Checklist: Academic writing

I avoid informal terms and contractions .

I avoid second-person pronouns (“you”).

I avoid emotive or exaggerated language.

I avoid redundant words and phrases.

I avoid unnecessary jargon and define terms where needed.

I present information as precisely and accurately as possible.

I use appropriate transitions to show the connections between my ideas.

My text is logically organized using paragraphs .

Each paragraph is focused on a single idea, expressed in a clear topic sentence .

Every part of the text relates to my central thesis or research question .

I support my claims with evidence.

I use the appropriate verb tenses in each section.

I consistently use either UK or US English .

I format numbers consistently.

I cite my sources using a consistent citation style .

Your text follows the most important rules of academic style. Make sure it's perfect with the help of a Scribbr editor!

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Taboo words in academic writing

- How to write more concisely

- Transition Words & Phrases | List & Examples

More interesting articles

- A step-by-step guide to the writing process

- Active vs. Passive Constructions | When to Use the Passive Voice

- Avoid informal writing

- Avoid rhetorical questions

- Be conscious of your adverb placement

- Capitalization in titles and headings

- Exclamation points (!)

- First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation

- Forging good titles in academic writing

- Free, Downloadable Educational Templates for Students

- Free, Downloadable Lecture Slides for Educators and Students

- How to avoid repetition and redundancy

- How to write a lab report

- How to write effective headings

- Language mistakes in quotes

- List of 47 Phrasal Verbs and Their One-Word Substitutions

- Myth: It’s incorrect to start a sentence with “because”

- Myth: It’s an error to split infinitives

- Myth: It’s incorrect to start a sentence with a coordinating conjunction (and, but, or, for, nor, yet, so)

- Myth: Paragraph transitions should be placed at the ends of paragraphs

- Tense tendencies in academic texts

- Using abbreviations and acronyms

- What Is Anthropomorphism? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Sentence Case? | Explanation & Examples

- What Is Title Case? | Explanation & Worksheet

- Writing myths: The reasons we get bad advice

- Writing numbers: words and numerals

What is your plagiarism score?

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ ed-i- tawr -ee- uh l , - tohr - ]

- an article in a newspaper or other periodical or on a website presenting the opinion of the publisher, writer, or editor .

- a statement broadcast on radio or television that presents the opinion of the owner, manager, or the like, of the program, station, or channel.

- something regarded as resembling such an article or statement, as a lengthy, dogmatic utterance.

editorial policies;

editorial skills.

editorial page;

editorial writer.

an editorial employee; an editorial decision, not an advertising one.