Essay Service Examples Literature The Notebook

Essay on ‘The Notebook’

Introduction

Themes of love and romance.

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

The Importance of Memory

Character development, narrative structure, symbolism and imagery.

Our writers will provide you with an essay sample written from scratch: any topic, any deadline, any instructions.

Cite this paper

Related essay topics.

Get your paper done in as fast as 3 hours, 24/7.

Related articles

Most popular essays

- Communication in Relationships

- The Notebook

'The Notebook' is a timeless romantic film that not only captivates viewers with its heartfelt...

- Book Review

- Reading Books

'The Notebook' by Nicholas Sparks is a poignant and captivating love story that has touched the...

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Neuroscience

Memory loss and cognitive decline are common symptoms among people diagnosed with Dementia. Over...

The film The Notebook, directed by Nick Cassavetes is a romantic drama. The film takes place in a...

- Film Analysis

- Movie Review

'The Notebook,' directed by Nick Cassavetes, is a renowned romantic drama that has captivated...

- Hamlet Revenge

Death becomes a frequent and almost normal event throughout Hamlet, by William Shakespeare. The...

Throughout both Ozymandias and London, the poets portray power through the corruption of both the...

- Educational System

Drama involves performance and it has been used as a tool in the line of education, it involves...

- Kate Chopin

- The Awakening

Kate Chopin was a female author of New Orleans. She was notable for writing rather controversial...

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via [email protected].

We are here 24/7 to write your paper in as fast as 3 hours.

Provide your email, and we'll send you this sample!

By providing your email, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy .

Say goodbye to copy-pasting!

Get custom-crafted papers for you.

Enter your email, and we'll promptly send you the full essay. No need to copy piece by piece. It's in your inbox!

Joan Didion on Keeping a Notebook

By maria popova.

After citing a seemingly arbitrary vignette she had found scribbled in an old notebook, Didion asks:

Why did I write it down? In order to remember, of course, but exactly what was it I wanted to remember? How much of it actually happened? Did any of it? Why do I keep a notebook at all? It is easy to deceive oneself on all those scores. The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself. I suppose that it begins or does not begin in the cradle. Although I have felt compelled to write things down since I was five years old, I doubt that my daughter ever will, for she is a singularly blessed and accepting child, delighted with life exactly as life presents itself to her, unafraid to go to sleep and unafraid to wake up. Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss. […] The point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking. That would be a different impulse entirely, an instinct for reality which I sometimes envy but do not possess.

To that end, she confesses a lifelong failure at keeping a diary:

I always had trouble distinguishing between what happened and what merely might have happened, but I remain unconvinced that the distinction, for my purposes, matters.

What, then, does matter?

How it felt to me: that is getting closer to the truth about a notebook. I sometimes delude myself about why I keep a notebook, imagine that some thrifty virtue derives from preserving everything observed. See enough and write it down, I tell myself, and then some morning when the world seems drained of wonder, some day when I am only going through the motions of doing what I am supposed to do, which is write — on that bankrupt morning I will simply open my notebook and there it will all be, a forgotten account with accumulated interest, paid passage back to the world out there: dialogue overheard in hotels and elevators and at the hat-check counter in Pavillon (one middle-aged man shows his hat check to another and says, ‘That’s my old football number’); impressions of Bettina Aptheker and Benjamin Sonnenberg and Teddy (‘Mr. Acapulco’) Stauffer; careful aperçus about tennis bums and failed fashion models and Greek shipping heiresses, one of whom taught me a significant lesson (a lesson I could have learned from F. Scott Fitzgerald, but perhaps we all must meet the very rich for ourselves) by asking, when I arrived to interview her in her orchid-filled sitting room on the second day of a paralyzing New York blizzard, whether it was snowing outside. I imagine, in other words, that the notebook is about other people. But of course it is not. I have no real business with what one stranger said to another at the hat-check counter in Pavillon; in fact I suspect that the line ‘That’s my old football number’ touched not my own imagination at all, but merely some memory of something once read, probably ‘The Eighty-Yard Run.’ Nor is my concern with a woman in a dirty crepe-de-Chine wrapper in a Wilmington bar. My stake is always, of course, in the unmentioned girl in the plaid silk dress. Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point. It is a difficult point to admit. We are brought up in the ethic that others, any others, all others, are by definition more interesting than ourselves; taught to be diffident, just this side of self-effacing. (‘You’re the least important person in the room and don’t forget it,’ Jessica Mitford’s governess would hiss in her ear on the advent of any social occasion; I copied that into my notebook because it is only recently that I have been able to enter a room without hearing some such phrase in my inner ear.) Only the very young and the very old may recount their dreams at breakfast, dwell upon self, interrupt with memories of beach picnics and favorite Liberty lawn dresses and the rainbow trout in a creek near Colorado Springs. The rest of us are expected, rightly, to affect absorption in other people’s favorite dresses, other people’s trout.

Once again, Didion returns to the egoic driver of the motive to write :

And so we do. But our notebooks give us away, for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable “I.” We are not talking here about the kind of notebook that is patently for public consumption, a structural conceit for binding together a series of graceful pensées ; we are talking about something private, about bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker.

Ultimately, Didion sees the deepest value of the notebook as a reconciliation tool for the self and all of its iterations:

I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were. […] It is a good idea, then, to keep in touch, and I suppose that keeping in touch is what notebooks are all about. And we are all on our own when it comes to keeping those lines open to ourselves: your notebook will never help me, nor mine you.

The rest of Slouching Towards Bethlehem is brimming with the same kind of uncompromising insight, sharp and soft at the same time, on everything from morality to marriage to self-respect . Complement this particular portion with celebrated writers on the creative benefits of keeping a diary .

— Published November 19, 2012 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/11/19/joan-didion-on-keeping-a-notebook/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, culture joan didion writing, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

The Notebook

Nicholas sparks, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Eighty-year-old Noah Calhoun , who lives in a nursing home in North Carolina, describes the lonely and sometimes painful nature of his final days. Noah knows that he has lived an ordinary life by most people’s standards, but he insists that having known “perfect love” has been enough for him. Noah wanders down the cold halls of the nursing home to visit the room of another patient—a woman—who barely acknowledges him as he sits down beside her, opens up a small notebook , and begins to read to her. Noah is hopeful that today will be the day a miracle happens.

The story flashes back to October of 1946. As dusk falls, Noah sits on the porch of his sprawling home in New Bern, North Carolina. Noah is proud of the work he’s done on the old plantation house—a few weeks ago, a reporter even came to interview him about it and take pictures. Noah is a simple man who spends his days kayaking, reading poetry, and playing guitar with his neighbor Gus . But all the while, Noah pines for a lost love: in 1932, he shared an intense, romantic summer with a young woman named Allie Nelson whose family came to visit New Bern for several months. At the end of the summer, after losing their virginities to each other, Noah and Allie parted ways. Though Noah wrote Allie many letters, she never answered them, and he has not heard from her or seen her since.

The following morning, Allie arrives in New Bern from Raleigh to visit Noah—and to tell him about her engagement to the wealthy lawyer Lon Hammond, Jr. Allie has recently read a newspaper article about Noah’s renovated house and, in the weeks since, has been unable to think of anything else—even though her wedding to Lon is just weeks away. Allie has come to New Bern under the guise of going antiquing. As Allie bathes, dresses, and gathers her courage to head out to visit Noah, the narrative switches back to Noah’s point of view as he reflects on the years since Allie’s departure from New Bern. After heading up north in search of work at the height of the Great Depression, Noah found a job at a scrap yard owned by the kindly Morris Goldman , a man who took a shine to Noah. When Noah returned from fighting in World War II, he found that Morris had left him a significant portion of the company. Noah bought the plantation house and the surrounding land with the funds, and in the 11 months since, he’s dedicated himself day and night to fixing up the property. Lost in thought, Noah finishes his daily tasks, showers, and sits out on the porch. He is surprised when he spots a car coming down the drive—and he is even more shocked when Allie steps out of it.

After standing and staring at each other, Allie and Noah embrace excitedly. Allie tells Noah about having found the article and compliments him on his beautiful handiwork. She apologizes for showing up out of the blue, but Noah assures her that he’s excited to see her. Allie tells Noah about her engagement, and the two of them take a walk down to the river. As Allie tells Noah about Lon, he senses hesitation in her voice. Noah invites Allie to stay for dinner, and she accepts. Allie and Noah continue reminiscing about their summer together as they prepare dinner and tour the house. When Noah asks Allie why she never answered his letters, she becomes confused—she says she never got any letters. Soon, Allie realizes that her mother, Anne , who disapproved of Noah for being of a lower social class, must have confiscated the letters. Noah asks Allie if she thinks they’d still be together if she had gotten the letters, and she admits that she thinks they would be.

Noah then asks Allie about Lon and about her passion for painting , Allie admits that she gave art up despite going to college for it. Noah takes Allie to the living room and shows her that he has hung a painting she gave him long ago over the fireplace—he assures her that she is a true artist and should give painting another shot. Over dinner, Allie realizes that she and Lon never talk as freely as she’s conversing with Noah. After dinner, as Noah reads Allie poetry on the porch, Allie feels a sensual stirring inside of her and thinks that she doesn’t feel this kind of passion for Lon. Overwhelmed, Allie leaves in a hurry. As Noah walks her to her car, he invites her back the following day. Allie accepts his invitation and returns to the inn, unaware that Lon has been trying to call her room all night long.

The next day, as Allie and Noah enjoy their separate mornings, they find themselves lost in thoughts of each other. Noah kayaks as he does every morning, while Allie heads to a department store to purchase some art supplies and make a couple of quick sketches. At noon, Allie drives out to Noah’s, where Noah tells her he is taking her for a surprise. Allie follows Noah down to the river and hops into his canoe. The two set off down the river, again reminiscing about their summer of love as they paddle downstream. When Noah turns off into a small lake, he tells Allie to close her eyes. When she opens them again, she finds that Noah has led them to a secluded cove—they are surrounded by hundreds of swans. After feeding the birds, Allie and Noah notice thunder and lightning approaching. They begin rowing home, but they get trapped in the storm anyway. Allie laughs rapturously as she and Noah are soaked to the bone. Back at the house, Allie and Noah sit in front of the fireplace and sip bourbon as they continue reminiscing about the summer of 1932. When Allie asks Noah if he recalls having sex at the end of the summer, neither of them can resist their feelings any longer. Overcome by passion, the two have sex by the fire. Meanwhile, back in Raleigh, Lon asks for an adjournment in the case he’s working on. He tells the judge he has urgent business to attend to over the weekend, and the judge urges him to be back by Monday at nine. Lon accepts the judge’s mandate and hurries to his car to begin the drive to New Bern.

The next morning, Allie and Noah are in the kitchen when there is a knock at the door. Noah goes to answer it—and he’s shocked to find himself face to face with Allie’s mother, Anne Nelson. Noah welcomes Anne in, and he and Allie sit with her in the living room. Anne tells Allie that she’s noticed her behavior was strange for weeks—and she knew it had to be due to the article about Noah. Anne warns Allie that Lon is on the way—he called the house last night deeply upset, having figured out what Allie was doing in New Bern. Before leaving, Anne gives Allie the letters from Noah and urges her to “follow [her] heart” as she chooses what path her life will take. After Anne leaves, Noah asks Allie what she wants to do. She tells him she is afraid of hurting or upsetting anyone. Noah, however, insists that Allie must do what she wants to do—she must live a life which doesn’t constantly force her to keep looking back and wondering what could have been. Allie begins crying, and Noah tells Allie he already knows she won’t stay. He walks her to her car and helps her inside. He tells her he loves her before she starts the engine, but Allie stoically begins driving away without looking back. Allie continues crying all the way to the inn. When she arrives, she spots Lon’s car in the parking lot. She turns off the engine and reads Noah’s final letter to her, from March of 1935, as she puzzles over what to say to Lon. By the time Allie is finished reading Noah’s last note, she knows exactly what to say, and she heads into the inn with purpose.

The narrative returns to the frame story in the future. Noah finishes reading the notebook and closes it. His female companion—whom readers can now infer is Allie—is comforted by the story and asks if Noah wrote it himself. Noah says that while he didn’t write it, it is a true story. Allie tells Noah that she has a question for him but doesn’t want to hurt his feelings—she asks him, confusedly, who he is. Noah becomes lost in thought as he reflects on the full, beautiful life he and Allie made together. They have four children and many grandchildren, and Allie is a world-famous painter—yet most days, her Alzheimer’s disease prevents her from remembering any of this. Nevertheless, Noah reads to Allie each day in hopes of jogging her memory and enjoying just a few lucid moments with her. Noah spends much of his free time reading old letters and looking at old photographs, reminiscing about the past.

One day, Noah invites Allie on a walk, and she accepts. Together, as they walk the grounds of the nursing home, Allie continues asking questions about the story and inquiring about Noah’s own life. Allie tells Noah that she believes she has a secret admirer—she tells him she often finds notes and poems tucked into her coat pockets or under her pillow. Noah chuckles and leads Allie back up to her room, where the nurses have set out a candlelight dinner for the two of them. The nurses are charmed by Noah’s devotion to Allie and help him woo her every chance they get. As Allie and Noah sit down to dinner and listen to music playing on the stereo, Allie recognizes Noah and tells him she’s always loved him. The two of them enjoy a couple of blissful hours together eating and talking—but soon, Allie begins fading away again. She is suddenly unable to recognize Noah and begins screaming for the nurses, who come down the hall to sedate her and remove Noah from her room.

Noah endures several lonely, foggy days without Allie. One morning, while looking through old letters again, he experiences pain, numbness, and loss of vision—he knows he is having a stroke. After two weeks of being intubated and moving in and out of consciousness, Noah is finally cleared to return to the nursing home. On his first night back, he spends hours losing himself in old letters, photos, and memories before shuffling down the hall toward Allie’s room, having missed her terribly. Though Noah is not supposed to visit Allie after dark, the night nurse, Janice , lets Noah pass. She tells him how much she admires him and how inspired she is by his and Allie’s enduring love. In Allie’s room, Noah sits at the edge of the bed and slips a poem beneath her pillow as she sleeps. He cannot stop himself from caressing her face. Allie wakes and turns to face him. Noah is afraid she won’t recognize him and will begin screaming—but instead, she smiles and addresses him by name, tells him how deeply she’s missed him, and begins undoing the buttons of his shirt.

Themes and Analysis

The notebook, by nicholas sparks.

At the core of 'The Notebook' is the relationship between the heart and the mind, feelings, and memories. The themes, symbols and key moments in the novel are discussed here.

Article written by Israel Njoku

Degree in M.C.M with focus on Literature from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

‘ The Notebook ‘ by Nicholas Sparks captures themes and symbols with philosophical and psychological implications, particularly on the issue of the relationship between feelings and memories. It begs the question, how much do our memories shape our feelings? The novel is small in volume but mighty in its ability to provoke thoughts and introspection.

Like books such as ‘ Romeo and Juliet ‘ by William Shakespeare and ‘ Pride and Prejudice ‘ by Jane Austen , the familiar theme of love is found in ‘ The Notebook ‘ by Nicholas Sparks. Also, there are other less popular but important themes, such as aging, memory, beauty in nature, and class discrimination in this novel. Let’s take a close look at some of these themes here.

Enduring Love

In ‘ The Notebook ,’ love is remarked as a force capable of overcoming all odds, be it social class, science, time, age, or physical ailment. Love is a powerful value capable of bringing life and restoring purpose to life regardless of whatever challenges there may be. Noah and Allie fall in love as teenagers, but their nascent love faces many challenges. The first challenge is their separation when Allie moves with her family to a new city. The next challenge is interference from Allie’s parents, then Allie’s betrothal to another man. But Allie and Noah overcome all these challenges to their union and marry each other.

The challenges continue even in their blissful marriage. The death of one of their children and the loss of Allie’s mind are the greatest of these challenges. But it does not deter Noah from nurturing their love, and their union waxes stronger.

Aging and Mortality

A dominant setting in the novel is a nursing home for old people, where we see several inmates, including the protagonists passing through several levels of physical debilitation as a result of their old age. The novel remarks on the inevitable deterioration of the mortal human body with time and that this deterioration must eventually lead to death.

From the perspective of old age, the narrator rues the folly of wasting one’s limited time in life chasing things that will not matter in the long run at the expense of eternal values like love.

‘ The Notebook ‘ by Nicholas Sparks also highlights some of the differences between the mind, body, and behavior of young people and old people.

Memories and Feelings

One of the other ascendant themes of ‘ The Notebook ‘ is the existential argument that feelings are much beyond what the mind can comprehend and that memory is only a peripheral value when juxtaposed with feelings.

This is best explained in the complexities of Allie’s interactions with Noah as she suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease wiped Allie’s mind clean of all her memories, including the memory of her soul mate and lifelong lover, Noah. Yet, she feels a connection with him and feels safe in his company despite her inability to recognize him. Sometimes, the power of Allie’s feelings for Noah defies her disease, and she is able to recall memories of him.

Nicholas Sparks suggests in ‘ The Notebook ‘ that the workings of the human mind are not only controlled by experience and memories but also by feelings.

The Beauty of Nature

‘ The Notebook ‘ celebrates and pays tribute to nature in several ways. From Noah’s appreciation of and description of elements of nature to Allie’s art and paintings, we see a profound picture of the beauty of nature in flowers, the sky, swans, and trees, among others.

The characters Noah and Allie enjoy nature so much that the view of flowers and birds becomes both romantic and therapeutic to both of them.

Class Discrimination

‘ The Notebook ‘ by Nicholas Sparks frowns at the discrimination against people based on social class. In the novel, Allie’s parents try to put an obstacle between Allie and Noah because of their snobbish belief that Noah being from a poor family, is not good enough for their socialite daughter.

Class discrimination made Allie’s parents blind to Noah’s admirable qualities of kindness, hard work, and integrity. This made them stand in the way of their daughter’s happiness.

Analysis of Key Moments

- Noah is an eighty-year-old in a nursing home and goes to visit his wife, Allie, but Allie does not recognize him because she suffers from Alzheimer’s disease.

- Noah begins to read to Allie from a notebook that narrates a story from another timeline.

- Noah is a lonely young man back from the war and spending his fortune and energy refurbishing an old, abandoned house in New Bern, North Carolina.

- Young Allie is three weeks away from getting married to Lon Hammond, but she decides to visit Noah in New Bern before getting married.

- Allie and Noah reconnect and rekindle their love after a few dates together.

- Lon grows suspicious of Allie after she misses numerous calls he placed at the hotel where she is meant to be. He decides to go to New Bern and find out what is going on with her.

- Allie’s mother, Anne Nelson, rushes to New Bern to warn Allie that Lon is coming in search of her. She then gives Allie letters from Noah, which she had hitherto hidden from Allie.

- Allie goes to meet Lon and breaks up with him.

- Noah and Allie get married and have children, but with time Allie begins to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease.

- Noah and Allie both move to a nursing home, and Noah makes it a routine to go and read their love story to Allie every day.

Style, Tone, and Figurative Language

The style of the narration is a combination of the first-person narrative and the third-person narrative. The author also makes use of framing devices in the novel. A framing device is a narrative technique where a story is told amidst another story. Often, the beginning and ending chapters serve as frames for the story told in the chapters in between. As we have in ‘ The Notebook ,’ chapter one and chapter eight frame the story told in chapters two to seven.

The tone of the narrator is poetic and wistful, and there are figurative devices deployed in the narration, notably similes and metaphors.

Analysis of Symbols

Symbols are items that signify something abstract beyond what they are at surface value. Some of the symbols in ‘ The Notebook ‘ are:

Noah’s House

Beyond its practical utility as a shelter, Noah’s house in New Bern is an emblem of his dreams and his belief that dreams eventually come true through hard work, patience, and diligence.

The house is also a symbol of the dead things that can be brought to life by the power of love and attention.

Allie’s Painting

Allie’s painting is a symbol of her desires and ideals. At some point in her life, she lost sight of both values in her life, but the recovery of her art and talent in painting was symbolic of her acceptance of her true self.

The Storm and the Hearth

The Storm in ‘The Notebook ‘ symbolizes the challenges posed to Noah and Allie’s union. On the other hand, the hearth symbolizes a haven that Noah and Allie find with each other that protects them from the cold and dangers of the storm.

The notebook is a symbol of the power of words and stories in preserving memories, feelings, and enriching experiences. Allie, whose memory was failing her because of her disease, could only revive the passions of her past by listening to her story from the notebook.

What mental illness does Allie have in ‘ The Notebook ?’

Allie is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in ‘ The Notebook .’ The disease makes her lose memories of her identity, family, and her past.

What is the age difference between Noah and Allie in ‘ The Notebook ?’

The age difference between Noah and Allie is two years. Noah is two years older than Allie. They first began their relationship when Allie was fifteen years old and Noah seventeen.

Why is ‘ The Notebook ‘ regarded as unrealistic?

‘The Notebook’ by Nicholas Sparks is regarded as unrealistic by many because of the character Noah. Noah is too idealistic and without flaws that make him relatable as a character.

Who is the antagonist of ‘ The Notebook ‘ by Nicholas Sparks?

The antagonist of ‘ The Notebook’ is Allie’s mother, Anne Nelson. She poses as the major obstacle against the protagonists’ love and happiness.

Join Our Community for Free!

Exclusive to Members

Create Your Personal Profile

Engage in Forums

Join or Create Groups

Save your favorites, beta access.

About Israel Njoku

Israel loves to delve into rigorous analysis of themes with broader implications. As a passionate book lover and reviewer, Israel aims to contribute meaningful insights into broader discussions.

About the Book

Discover literature, enjoy exclusive perks, and connect with others just like yourself!

Start the Conversation. Join the Chat.

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

TWO WRITING TEACHERS

A meeting place for a world of reflective writers.

4 Purposes for a Writer’s Notebook: Notebooks as a Writer’s Tool

That sunny, summer day, I pulled the driver’s door closed of my grandmother’s 1978 Volkswagen Rabbit. My grandmother sidled in through the passenger door and took her seat beside me. Quickly she closed the door and folded her hands silently in her lap. Looking down nervously, I noticed the pedals. “Why are there three pedals?” I asked. I knew one was the gas pedal– that long one there– and I assumed one of the others to be the brake. But what about that third one? “It’s the clutch,” my grandmother explained. “When you shift into different gears, you have to push it down. That allows you to put the car into first gear, second gear, and so on.” At age fourteen, I felt a little bewildered. “Why?” I said aloud. My grandmother’s face lightened into an understanding smile. “Well, otherwise we’re not going anywhere. Here, let’s start the car and I’ll show you how the clutch works.”

Understanding the purpose of something can unlock a path forward. This was certainly the case with the clutch pedal in my grandmother’s Volkswagen. And although it required a great deal of practice to actually operate the clutch with ease and prowess, I soon became a pretty competent driver. This week, the authors of Two Writing Teachers are devoting digital ink to supporting teachers in thinking about the writer’s notebooks as an important writer’s tool. Today, let’s think about the various purposes of a notebook. Like understanding what role the clutch plays when driving a car with a manual transmission, understanding a few vital purposes of a writer’s notebook can support students in propelling their writing lives forward in meaningful, growth-oriented ways. And just like my grandmother went on to explain both the importance and the purpose of the clutch in an automobile, it is important that we share the importance, role, and purpose of writer’s notebooks with our students.

Purpose One: A Place to Write About Small Things. One of the most basic goals we probably hold for our writers is to write with meaning and focus. It is so important students know that one thing writers do, at a most basic level, is strive to craft ideas in service of a message, a point; in other words, meaning . Writers work tirelessly to answer the question, “What do I want my readers to know or to think after they have read my writing?” Oftentimes writers will use notebooks to hang on to fleeting ideas, jot some notes, capture a bit of thinking, etc. Thus, it can be helpful if we teach our young writers that one purpose of their notebooks can be to “write about small things,” which can be loosely translated to “work to write about focused ideas.”

One way some teachers have introduced this concept of focusing on small things is through the metaphor of a watermelon. While teaching in seventh-grade classrooms, I used to hang a sign that looked something like the one here:

This metaphor can help students understand the difference between a piece of writing that is full of seeds — too many! — and a piece of writing that grows from one, seemingly small “seed idea.” In narrative notebook entries, for example, we often focus on writing small moments in our lives. Rather than attempting to write about “My Summers at Grandma’s,” we might write about “The Time I Rode the Riding Lawn Mower at Grandma’s” or “The Time We Went Fishing at Grandma’s.” Kids often struggle with the concept of focusing writing around a tightly selected topic. In informational writing, for example, students often want to write everything there is to know (well, that they know) about the game of soccer (“Each team has eleven players on the field,” “there are two goals,” etc.). But from the outset of our workshops, if students understand the concept that one of the purposes of a writer’s notebook is to write about small things, this can help them to begin focusing right away.

Purpose Two: A Place to Practice Strategies Taught in Class. Writer’s notebooks have a second important purpose of providing a place to practice what we (their teacher) have taught them as writers. In this way, a writer’s notebook is distinct from a “journal.” A quick Google search of the word journal reveals a number of definitions related to “a place to keep records.” Perhaps you or even some of your students enjoy keeping a journal or diary in which you record events that have happened, along with your thoughts or reflections about those events. This is certainly a valuable endeavor with many benefits! However, we want to teach our young writers that a writer’s notebook is not that ; it is, as Betsy wrote, a writer’s tool. It is a place where students both live like writers and work to become stronger writers. As Lucy Calkins writes in The Common Core Writing Workshop (2014), “…there is a great deal of difference by what people mean by journal and what your students are doing. Journals are often containers for writing that have no audience…and that are never revised, edited, or published” (Heinemann, p. 42).

In this way, notebooks are kind of like a practice field. Growing up, my brother and I played on soccer teams. On the weekends, we loved to go out into our backyard and play soccer, oftentimes practicing moves and techniques our coaches (and friends) had taught us in team practices. Most professional sports teams practice in one place and play games in another. This metaphor can be brought to our writers! As their coaches, we want to encourage our students to work hard to improve; one way to do that is to practice, applying what they’ve learned to do in their notebooks. Aimee Buckner, author of Notebook Know-How: Strategies for the Writer’s Notebook (Stenhouse, 2005) once said,

“A Writer’s Notebook gives students a place to write everyday…to practice living like a writer. The purpose of a notebook is that it provides students the practice of simply writing. It’s a place for them to generate text, find ideas, and practice what they know about spelling and grammar. It’s the act of writing — the practice of generating text and building fluency — that leads writers to significance.”

Purpose Three: A Place to Experiment and Take Risks . A few years ago, I attended a workshop led by a Harvard Professor, Dr. David Dockterman. In his presentation entitled, “Developing Academic Mindsets for Literacy,” Dr. Dockterman enlightened everyone on a critical connection regarding the importance of risk-taking and learning. He said, “ We learn when we take risks. We learn when we do something we have not done before…otherwise we are not learning.” With this important understanding in mind, we want to invite our students to take risks in their writer’s notebooks. This can mean writing entries about very personal topics, trying out new craft moves you teach them or they learn from a mentor text, trying on unfamiliar topics, or however a writer feels he or she defines taking a risk. And knowing that risk-taking can be scary, it is also important that we model such writing behaviors for our students. We can say things like, “I’ve never tried this in my writing before…” or “I’m not sure how this is going to go, but…” Modeling our willingness to experiment can send the message that writers take risks. Writers experiment. Writers try stuff out.

A Place to Set Goals and Work to Meet Them. Getting better at something requires not just practice but deliberate practice. Often people do stuff year after year and do not get better–because getting better requires resolve! And it takes a ‘working on’ mindset. Therefore, we can consider inviting students to use the notebook to set goals and work to meet them. There are a few ways this can look:

- Volume goals: Sometimes students might work on a goal to write more, either in a single sitting or over a longer period of time. In the past, I have worked with students by asking them to run their finger down a page to a place they think they can write to in ten minutes and place an X. Then I’ll start a timer (sometimes a fictitious one) and leave them to work independently. With other students, I have worked with them on setting a volume goal for the week.

- Structure/Development goals: In October, I wrote about student checklists (that post is here ). Checklists that lay out clear learning targets can also be turned into writing goals by our student writers. After reviewing a draft, students can select a few places on the checklist where they may have marked “Not yet,” and copy or tape those boxes into their writer’s notebooks. Some teachers have even asked writers to save a special section of the notebook for goals, conference artifacts, etc.

- Writing Process goals: In her book The Writing Strategies Book , Jennifer Serravallo does a beautiful job laying out ten important categories that can help teachers and students identify writing goals, from composing with pictures, to conventions, to writing partnerships. One of her early blog posts summarizes those goals.

- Personal goals: Aside from pre-made checklist or teacher-negotiated goals, it is also worthwhile to ask students to reflect and think about what they want to work to get better at in their writing. Some have said, “I want to take more risks in my writing and try to reveal myself more,” or “I want to vary the tone of my writing,” or “I want to try to write more often.”

Eventually, over time, I became more skilled with using a clutch and shifting gears in Grammy’s old Volkswagen. It took time, practice, and patience. But with a clear goal in mind and lots of supportive coaching from my grandmother, I soon not only understood the purpose of a clutch, but was actually moving down the road. As teachers, if we are able to help our writers understand the purposes of their writer’s notebooks, chances are we can help set them up to be moving down the road of becoming stronger writers.

GIVEAWAY INFORMATION:

- For a chance to win this Skype session with Amy, please leave a comment about this or any blog post in this blog series by Sunday, November 11th at 6:00 p.m. EST. Betsy Hubbard will use a random number generator to pick the winner’s commenter number. His/her name will be announced in the ICYMI blog post for this series on Monday, November 12th.

- Please leave a valid e-mail address when you post your comment so Betsy can link you up with Amy if you win.

- If you are the winner of the Skype session, Betsy will email you with the subject line of TWO WRITING TEACHERS – AMY LV. Please respond to her e-mail with your mailing address within five days of receipt. A new winner will be chosen if a response isn’t received within five days of the giveaway announcement.

Share this:

Published by Lanny Ball

For more than 29 years, Lanny has taught, coached, presented, staff developed, and consulted within the exciting and enigmatic world of literacy. With unyielding passion and belief in the possibility of workshop teaching, Lanny has worked to support students, teachers, and school administrators around the country in outgrowing themselves as both writers and readers. Working first as a classroom teacher, then as a coach and TCRWP Staff Developer, Lanny is now a literacy specialist, working and living in the great state of Connecticut. Outside of literacy, he enjoys raising his three ambitious young daughters with his wife, and playing the piano. Find him on this blog, as well as on Twitter @LannyBall. Lanny is also a former co-author of a blog dedicated to supporting writing teachers and coaches that maintain classroom writing workshops, twowritingteachers.org. View all posts by Lanny Ball

5 thoughts on “ 4 Purposes for a Writer’s Notebook: Notebooks as a Writer’s Tool ”

Thanks for proposing four distinct purposes for note booking. This is especially helpful for new teachers who, without enough classroom experience, often struggle with purpose.

Notebooks feed a writer. They are the writers playground and place for discovery. (I do call mine a Writer’s Journal, though ;))

WRITING RADAR by Jack Gantos is one of the best books I’ve ever read! It gives kids a funny and relatable understanding of HOW to become the best writer you can be! I read about 5 minutes before every Writers Workshop to inspire my second graders.

How timely! Meeting with Middle School Teachers today… Reminders of “purpose” & “goals” are so helpful! Thank you!

I am starting writing journals for narrative writing in my 7th grade class today. My colleagues are Lucy Caulkins devotees…I like to create my own lessons…but they are generally the same ideas. I like timed writing, the watermelon poster, and just setting up the idea generator of this being a place to try.

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Why it's important to keep a notebook

It is a good idea to keep in touch with old selves, Joan Didion once wrote

- Newsletter sign up Newsletter

I've been doing some research into notebooks and the like. A friend of mine pointed me towards a Joan Didion essay, "On Keeping A Notebook," that appears in Slouching Towards Bethlehem , a collection of her essays.

Written long ago, in the 1960s I think, the essay is still relevant. In fact, you could make an argument that in the world of blogging and Twitter, it's more relevant than ever.

Reading an arbitrary entry from her notebook, "that woman Estelle is partly the reason why George Sharp and I are separated today," Didion goes on to wonder:

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why did I write it down? In order to remember, of course, but exactly what was it I wanted to remember? How much of it actually happened? Did any of it? Why do I keep a notebook at all? It is easy to deceive oneself on all those scores. The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself. I suppose that it begins or does not begin in the cradle. Although I have felt compelled to write things down since I was five years old, I doubt that my daughter ever will, for she is a singularly blessed and accepting child, delighted with life exactly as life presents itself to her, unafraid to go to sleep and unafraid to wake up. Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss. [Slouching Towards Bethlehem]

The point of keeping a notebook, then:

So the point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking. That would be a different impulse entirely, an instinct for reality which I sometimes envy but do not possess. [Slouching Towards Bethlehem]

Recalling her failure to keep a keep a diary she touches on our ability to shape memories while we codify them.

At no point have I ever been able successfully to keep a diary; my approach to daily life ranges from the grossly negligent to the merely absent, and on those few occasions when I have tried dutifully to record a day's events, boredom has so overcome me that the results are mysterious at best… [Slouching Towards Bethlehem]

But if the boredom of daily events doesn't matter, what does?

I sometimes delude myself about why I keep a notebook, imagine that some thrifty virtue derives from preserving everything observed. See enough and write it down, I tell myself, and then some morning when the world seems drained of wonder, some day when I am only going through the motions of doing what I am supposed to do, which is write — on that bankrupt morning I will simply open my notebook and there it will all be, a forgotten account with accumulated interest, paid passage back to the world out there: dialogue overheard in hotels and elevators and at the hat-check counter in Pavillon...

I imagine, in other words, that the notebook is about other people. But of course it is not. I have no real business with what one stranger said to another at the hat-check counter in Pavillon... My stake is always, of course, in the unmentioned girl in the plaid silk dress. Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point. [Slouching Towards Bethlehem]

I think for Didion her notebook was an escape. She was "brought up in the ethic that others, any others, all others, (were) by definition more interesting than (her)." The notebook was an escape.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

[O]ur notebooks give us away, for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable "I." … [W]e are talking about something private, about bits of the mind's string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its maker. [Slouching Towards Bethlehem]

In the end the deepest value of notebooks to her was not to remember the line but the memory, "I should remember the woman who said it and the afternoon I heard it." To reconnect with another iteration of herself.

Perhaps it is difficult to see the value in having one's self back in that kind of mood, but I do see it; I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind's door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were. I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be; one of them, a seventeen-year-old, presents little threat, although it would be of some interest to me to know again what it feels like to sit on a river levee drinking vodka-and-orange-juice and listening to Les Paul and Mary Ford and their echoes sing "How High the Moon" on the car radio. (You see I still have the scenes, but I no longer perceive myself among those present, no longer could even improvise the dialogue.)

…It is a good idea, then, to keep in touch, and I suppose that keeping in touch is what notebooks are all about. And we are all on our own when it comes to keeping those lines open to ourselves: your notebook will never help me, nor mine you. [Slouching Towards Bethlehem]

Like so much of what I read, I'm new to Didion. Slouching Towards Bethlehem , her first work of non-fiction, is interesting throughout.

More from Farnam Street...

- The human search for meaning

- 11 rules for critical thinking

- What the most successful people do before breakfast

Under the Radar Malaysia targets traditional seafaring Bajau Laut tribe in crackdown on undocumented migrants

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published 8 July 24

Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - Fizzling out, outrageous misfortune, and the branches of government

By The Week US Published 7 July 24

Cartoons Artists take on accountability, the Constitution, and more

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Advertise With Us

The Week is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

Kelly Danckert

Just another umass boston blogs site.

“On Keeping a Notebook”

September 9, 2015 by kellydanckert001 | 0 comments

Joan Didion’s essay opens on an incredibly personal note: a confession of sorts of why she and who the reader assumes to be her significant other, broke up. It’s a snapshot of her life at a single moment in time; a single sentence accompanied by the date and where Didion was when she wrote it. The reader is left with questions Didion goes on to ask her. What was she doing in Delaware? “Waiting for a train, missing a train?” As Carl H. Klaus points out in his piece “Essayists on the Essay,” Didion’s essay is personal, free, and unfolds slowly and in a way that mimics how she is processing the information she’s writing about.

Didion goes on to answer a broader question: why keep a notebook? The way she answers this questions, however, reflects the characteristics of the essay that Klaus talks about. Didion could have made this piece a persuasive one, where she talks about the reasons people should keep a notebook or she could have made it more like an article where she writes about the benefits of keeping a notebook. Instead, she answers the questions as she’s mulling it over herself. The essay isn’t set up in a way that is a purposeful, methodical exploration of the subject, it’s simply an exploration of her thoughts.

After listing off some potential personal reasons for keeping a notebook, Didion seems to reach a conclusion. She says, “So the point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking.” The way she writes makes it seem as though she came to this conclusion through writing about it. It wasn’t an answer she found by thinking about it beforehand and then deciding to write it down, but instead by working through it with words and internal musings.

This is one of the main distinctions Klaus makes between an article and an essay. He says there is a “personal orientation of the essay and the factual mode of the article.” He goes on to say the article is “out of touch with human concerns.”

The driving force behind Didion’s piece “On Keeping a Notebook” is her voice and personal connection throughout. The narrative is freer, more open, and consists more of impressions and thoughts than fact. It is this personal voice and casual exploration of why she chooses to keep a notebook that is one of the defining traits of an essay that Klaus explains in his piece.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Required fields are marked * .

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Craft Essays

- Teaching Resources

On Keeping a (Writing) Notebook (or Three)

Randon Billings Noble

In her essay “ On Keeping a Notebook, ” Joan Didion writes about the odd notes she has taken over the years – on conversations she has overheard (“That woman Estelle is partly the reason why George Sharp and I are separated today”), facts she has learned (“during 1964, 720 tons of soot fell on every square mile of New York City”), and observations she has made (“Redhead getting out of car in front of Beverly Wilshire Hotel, chinchilla stole, Vuitton bags with tags reading: MRS LOU FOX / HOTEL SAHARA / VEGAS). She writes that each note “presumably has some meaning to me …” but admits that she can’t always recall what it is. For her the point is to “[r]emember what it was to be me.”

That’s what I use a journal for – not a notebook. Perhaps these classifications are splitting hairs, but Didion sees a difference, too. She claims that at

no point have I ever been able successfully to keep a diary; my approach to daily life ranges from the grossly negligent to the merely absent, and on those few occasions when I have tried dutifully to record a day’s events, boredom has so overcome me that the results are mysterious at best. What is this business about “shopping, typing piece, dinner with E, depressed”? Shopping for what? Typing what piece? Who is E? Was this “E” depressed, or was I depressed?

I would split the hair again and claim that there’s a difference between a diary and a journal – that it’s sort of like the difference between an autobiography and a memoir: in a diary you record each day’s events and in a journal you write whatever you want about your day whenever you want to write about it. For Didion, though, it’s all about the notebook.

I, too, keep a notebook – a writing notebook – and when I mentioned this during a presentation I gave on research in creative nonfiction, a hand in the audience immediately shot up: What did I write in my writing notebook? Some writers are dismissive of these kinds of questions – do you write in a notebook or on a computer, what kind of pen do you use, what kind of paper? But I’m happy to talk about the physical practicalities of craft – I want to know about your Pilot G-2 and your Clairefontaines. And I’m happy to talk about the content, too. When I answered the question many people took notes – perhaps in their writing notebooks. Here’s a version of what I said:

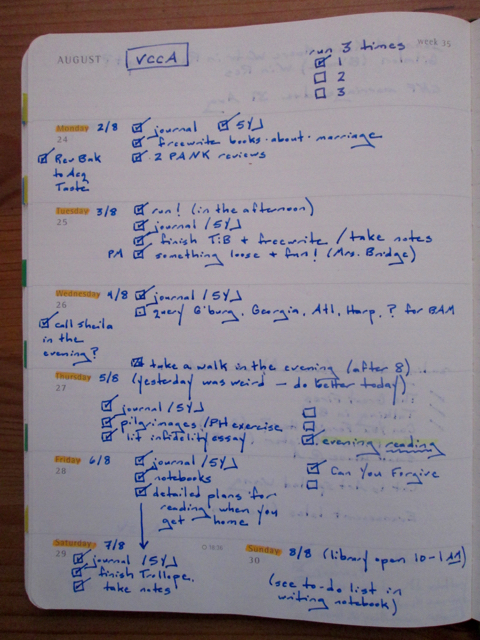

I keep three versions of a writing notebook: a journal, a writing notebook, and a writing planner.

In my journal I write down what happens to me, what I’m thinking about, occasional random observations, lists – the usual stuff you’d write in a journal. But I include this under “writing notebooks” because (especially as a writer of creative nonfiction) I often look back on journals to remember a certain time or place or person or line of thought – although I never write in my journal with this in mind. I write here solely as a person – not a writer.

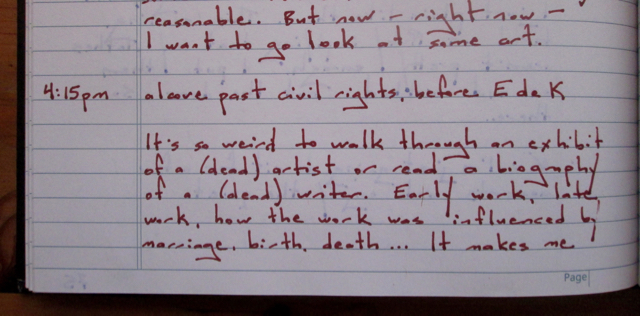

Here is a journal entry I made on May 11, 2015, after walking through an Elaine de Kooning exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery:

In my “official” writing notebook I jot down ideas for writing projects, make lists for writing projects, and write sketches of writing projects. Often I’ll start writing towards a draft but without any sense of where I’m headed. Writing by hand takes the pressure off: I can’t send ripped-out notebook pages to The New Yorker . But when a piece moves from my notebook to my computer and eventually (sometimes) to publication, I can see that long passages are often exactly the same as when I wrote them by hand the first time.

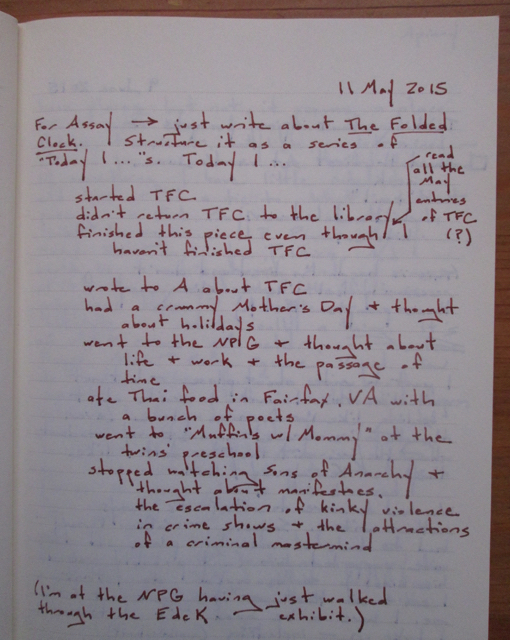

This is what I wrote in my writing notebook soon after the journal entry above:

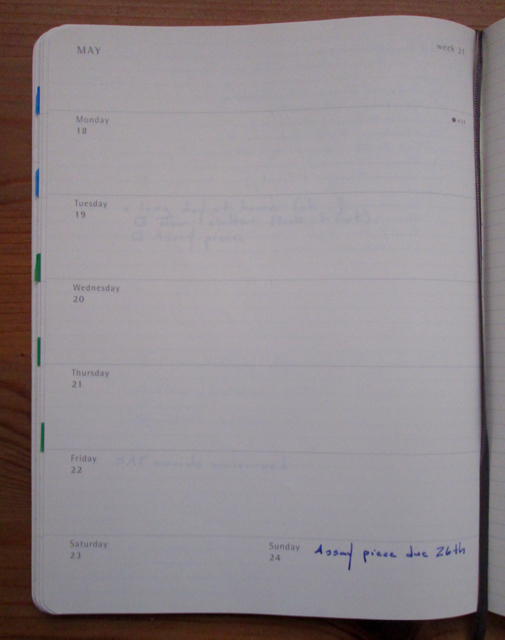

Then there’s my writing planner, the newest addition to my series of writing notebooks. It’s a Moleskine “weekly notebook” that has a calendar page laying out the days of the week on the left side and plain lined pages on the right side. I use this for short- and long-term planning. When I hear of a submission, contest, or application deadline I write it down on the calendar side; then I flip back a few weeks (or months) and write a reminder on the notebook side. On Sundays, a day I usually have a long swath of time to myself, I flip to the next week and write some plans. Then, during the week, when I have an hour or two to myself, I open my writing planner and do what it tells me (this is especially useful when the demands of everyday life are so crushing I can’t think straight). If I find that I can’t manage much I flip ahead a week or two and write “don’t forget about [idea]” and try again then. Every so often I flip back to look for unchecked boxes. It’s a lovely tool for preservation – and for looking and planning ahead to, say, a retreat or residency.

Here is a not-so-productive week in my writing planner (with only a deadline reminder for my piece about The Folded Clock ):

And here is a very productive week at the glorious Virginia Center for the Creative Arts :

What would Joan Didion think of all these notebooks? I smile/shudder to think. But my writing notebooks keep me writing – through rejection, triumph, inspiration, and disenchantment; in the face of preschooler twins, tantrums, field trips, and snow days; on the crests and in the troughs; at home and away – all the months of the year.

Randon Billings Noble is an essayist. Her work has appeared in the Modern Love column of The New York Times, The Georgia Review, The Rumpus, Shenandoah, Brevity, Fourth Genre and elsewhere. She is a nonfiction editor at r.kv.r.y quarterly , Reviews Editor at Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and a reviewer for The A.V. Club . You can read more of her work at www.randonbillingsnoble.com .

50 comments

| says: Jan 19, 2016 |

| says: Jan 20, 2016 |

| says: Jan 21, 2016 |

| says: Jan 22, 2016 | Thanks for this article. |

| says: Jan 28, 2016 |

| says: Feb 6, 2016 |

| says: Feb 4, 2016 |

| says: Feb 10, 2016 |

| says: Feb 10, 2016 |

| says: Feb 10, 2016 |

| says: Feb 11, 2016 |

| says: Feb 11, 2016 |

| says: Feb 12, 2016 |

| says: Feb 12, 2016 | The problem is, it’s far from organised. I’m going to put your advice into practice and (hopefully) untangle this muddled brain of mine! |

| says: Feb 12, 2016 | Does anyone have any other section ideas? This entry was very helpful. Thank you for sharing. |

| says: Feb 13, 2016 |

| says: Feb 13, 2016 | Lately, I find myself staring at the Moleskin notebooks at the bookstore–then chiding myself for wanting to spend so much more money than is necessary, and then drifting past them again before I leave the bookstore. I wonder what that is all about. |

| says: Feb 13, 2016 | I really enjoy your blog. Can’t wait to read more. |

| says: Feb 18, 2016 |

| says: Feb 19, 2016 | if anyone’s interested. |

| says: Feb 21, 2016 |

| says: Feb 25, 2016 |

| says: Apr 7, 2016 |

| says: Oct 17, 2016 |

| says: May 25, 2017 |

| says: Dec 18, 2017 |

| says: Mar 29, 2019 |

| says: Jan 2, 2020 |

| says: Jan 19, 2024 |

| Name required | Email required | Website |

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

© 2024 Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction. All Rights Reserved!

Designed by WPSHOWER

- Our Mission

Getting the Most Out of the Reader’s Notebook

Teaching reading using interactive notebooks can increase students’ intrinsic motivation to read.

Like other upper elementary educators, I’m always thinking about ways to help my students succeed as readers. When it comes to reading, we often hear terms like comprehension , summarizing , background knowledge , and vocabulary . But I want students to experience the joys, not just the techniques, of literacy.

I’ve been fortunate to participate in a reading fellowship at the Cotsen Foundation for the Art of Teaching , where my mentor and I sat down to create a yearlong goal; mine was an inquiry: “This year,” I wrote, “I will create content structured for high-level learning so that students will deepen their thought process about the stories and characters they read as demonstrated in their reader’s notebooks and conversations.”

To the naked eye, a reader’s notebook is an ordinary spiral-bound notebook. However, over the course of a school year in my classroom, the notebook takes on its own identity. It becomes a space for students to reflect on what they are reading, and when students look back over their entries, they witness their growth as readers.

The notebooks allow me, as a teacher, to take a genuine look at what reading strategies students absorb and what books they’re interested in. Here’s how to make the reader’s notebook meaningful in your classroom.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

In their book What Do I Teach Readers Tomorrow? , Gravity Goldberg and Renee Houser share that when they asked students why they thought the reader’s notebook was important, students answered with remarks like “To show the teacher I did my work.”

At the beginning of the year, I occasionally meet students with a similar mindset. Instead of thinking deeply about reading, a student may be stuck in “all done” mode, meaning they’ve read silently, and that’s all they’re going to do.

Sometimes reader’s notebooks become places to glue dittos (duplicated worksheets); these may look educational but don’t promote deep connections with texts. The goal of my reader’s notebooks is to create spaces where students can express themselves instead of merely filling out worksheets.

At times, teachers assign specific days for students to use notebooks, but I prefer to have a more fluid approach. During independent reading times, I place the notebooks next to my students. Some write reflections when they have an emotional reaction. It’s common for me to read, “I was shocked when…” or “I think…” Reading this language helps me see what they connect to. When the students go about it this way, the notebook is woven into the fabric of reading time and fosters more meaningful engagement.

Launching The Notebook

To implement the reader’s notebook, decide in advance when you’ll want students to use it. For example, it’s important to me that my students write about books they’re going to discuss with partners, so I have the students get them out from their bins in advance of that work.

Similar to a writer’s notebook, the reader’s notebook has to become a special space. To make each notebook warm and inviting, encourage your students to decorate their covers (my class had a sticker session).

Then, to give students more experience with the notebook, model specific reading and note-taking strategies during interactive read-alouds or groups. For example, at the end of an interactive read-aloud, I may say, “Stop and jot. What’s the author’s message?” Because students have practiced using the strategy during an interactive read-aloud, they can use it independently in their notebooks. Another strategy that I like to teach involves asking students what advice they may have for the main character of a story. This always helps my students think deeply about the character.

It’s important to remember that writing looks different for everyone. We should celebrate students’ thoughts about the stories they read. I frequently say to my students, “Which entry are you proud of this week?” They choose, and I hang the passage on the wall of my classroom. While drafting, revising, editing, and publishing work hold a value in the writing process, the reader’s notebook isn’t a book report; it allows us to celebrate the journey instead of the end result.

Scaffolding and Assessment

Many teachers are familiar with the use of sentence starters—using phrases as prompts for reflection. My opinion on them is mixed. I want meaningful reflection that comes from the hearts and minds of young readers. If a student feels successful reflecting with a meaningful sentence starter like “I predict…” or “I wonder…,” then I view the sentence starter as scaffolding. However, I want my students to make intrinsically motivated choices about which strategies they use, so I don’t assign particular sentence starters, instead allowing students to pick which ones resonate; as my students grow as readers, their thought processes around these scaffolds develop as well.

While a running record of student reflections may show me how the student answered questions about a passage of text, the reader’s notebook also shows me what specific reading strategies they can independently use. This type of documentation allows me to use the notebooks as a form of meaningful assessment.

Reader’s notebooks help me reflect on ways I can adjust my instruction. And they help me build more choice into reading curricula, since I get a sense of what resonates with my students. Reading is about planting seeds of knowledge. Reflecting in reader’s notebooks is an opportunity to watch those seeds grow.

The Notebook

31 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapters 1-3

Chapters 4-10

Chapters 11-12

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Do you remember your first love as well as Noah and Allie remember theirs? Discuss.

Do you believe that Allie returns to New Bern hoping to fall in love with Noah again? Why or why not?

Why do you believe that Allie’s mother keeps Noah’s letters for so many years after hiding them from Allie?

Related Titles

By Nicholas Sparks

A Bend in the Road

A Walk to Remember

Message In A Bottle

Nights in Rodanthe

The Best of Me

The Last Song

The Longest Ride

The Wedding

Featured Collections

View Collection

Valentine's Day Reads: The Theme of Love

Home / Essay Samples / Literature / The Notebook / The Notebook: Psychology in Nick Cassavetes’s Film

The Notebook: Psychology in Nick Cassavetes's Film

- Category: Psychology , Literature

- Topic: The Notebook

Pages: 3 (1241 words)

Views: 2535

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Self Concept Essays

Problem Solving Essays

Development Essays

Childhood Essays

Intelligence Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->