An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed, affiliation.

- 1 Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

- PMID: 28613597

- Bookshelf ID: NBK430847

Depression is a mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) classifies the depressive disorders into:

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

Major depressive disorder

Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Depressive disorder due to another medical condition

The common features of all the depressive disorders are sadness, emptiness, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function.

Because of false perceptions, nearly 60% of people with depression do not seek medical help. Many feel that the stigma of a mental health disorder is not acceptable in society and may hinder both personal and professional life. There is good evidence indicating that most antidepressants do work but the individual response to treatment may vary.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Disclosure: Suma Chand declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Hasan Arif declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

- Continuing Education Activity

- Introduction

- Epidemiology

- Pathophysiology

- History and Physical

- Treatment / Management

- Differential Diagnosis

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Similar articles

- Depression (Nursing). Chand SP, Arif H, Kutlenios RM. Chand SP, et al. 2023 Jul 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. 2023 Jul 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 33760492 Free Books & Documents.

- Letter to the Editor: CONVERGENCES AND DIVERGENCES IN THE ICD-11 VS. DSM-5 CLASSIFICATION OF MOOD DISORDERS. Cerbo AD. Cerbo AD. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2021;32(4):293-295. doi: 10.5080/u26899. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2021. PMID: 34964106 English, Turkish.

- Mood Disorder. Sekhon S, Gupta V. Sekhon S, et al. 2023 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. 2023 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 32644337 Free Books & Documents.

- [The difference between depression and melancholia: two distinct conditions that were combined into a single category in DSM-III]. Ohmae S. Ohmae S. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2012;114(8):886-905. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2012. PMID: 23012851 Review. Japanese.

- [Psychiatric and psychological aspects of premenstrual syndrome]. Limosin F, Ades J. Limosin F, et al. Encephale. 2001 Nov-Dec;27(6):501-8. Encephale. 2001. PMID: 11865558 Review. French.

- Salik I, Marwaha R. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2022. Sep 19, Electroconvulsive Therapy. - PubMed

- Singh R, Volner K, Marlowe D. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2023. Jun 12, Provider Burnout. - PubMed

- Ormel J, Kessler RC, Schoevers R. Depression: more treatment but no drop in prevalence: how effective is treatment? And can we do better? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;32(4):348-354. - PubMed

- Pham TH, Gardier AM. Fast-acting antidepressant activity of ketamine: highlights on brain serotonin, glutamate, and GABA neurotransmission in preclinical studies. Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Jul;199:58-90. - PubMed

- Namkung H, Lee BJ, Sawa A. Causal Inference on Pathophysiological Mediators in Psychiatry. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2018;83:17-23. - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in PubMed

- Search in MeSH

- Add to Search

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- NCBI Bookshelf

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, information, published in.

- Neuroanatomy

- Neurochemistry

- Neuroendocrinology

- Other Research Areas

Affiliations

Competing interests, export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

NEXT ARTICLE

Request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Six distinct types of depression identified in Stanford Medicine-led study

Brain imaging, known as functional MRI, combined with machine learning can predict a treatment response based on one’s depression “biotype.”

June 17, 2024 - By Rachel Tompa

Researchers have identified six subtypes of depression, paving the way toward personalized treatment. Damerfie - stock.adobe.com

Editor's note: This article was updated July 5 to include new research.

In the not-too-distant future, a screening assessment for depression could include a quick brain scan to identify the best treatment.

Brain imaging combined with machine learning can reveal subtypes of depression and anxiety, according to a new study led by researchers at Stanford Medicine. The study , published June 17 in the journal Nature Medicine , sorts depression into six biological subtypes, or “biotypes,” and identifies treatments that are more likely or less likely to work for three of these subtypes.

Better methods for matching patients with treatments are desperately needed, said the study’s senior author, Leanne Williams , PhD, the Vincent V.C. Woo Professor, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and the director of Stanford Medicine’s Center for Precision Mental Health and Wellness . Williams, who lost her partner to depression in 2015, has focused her work on pioneering the field of precision psychiatry .

Around 30% of people with depression have what’s known as treatment-resistant depression , meaning multiple kinds of medication or therapy have failed to improve their symptoms. And for up to two-thirds of people with depression, treatment fails to fully reverse their symptoms to healthy levels.

That’s in part because there’s no good way to know which antidepressant or type of therapy could help a given patient. Medications are prescribed through a trial-and-error method, so it can take months or years to land on a drug that works — if it ever happens. And spending so long trying treatment after treatment, only to experience no relief, can worsen depression symptoms.

“The goal of our work is figuring out how we can get it right the first time,” Williams said. “It’s very frustrating to be in the field of depression and not have a better alternative to this one-size-fits-all approach.”

Biotypes predict treatment response

To better understand the biology underlying depression and anxiety, Williams and her colleagues assessed 801 study participants who were previously diagnosed with depression or anxiety using the imaging technology known as functional MRI, or fMRI, to measure brain activity. They scanned the volunteers’ brains at rest and when they were engaged in different tasks designed to test their cognitive and emotional functioning. The scientists narrowed in on regions of the brain, and the connections between them, that were already known to play a role in depression.

Using a machine learning approach known as cluster analysis to group the patients’ brain images, they identified six distinct patterns of activity in the brain regions they studied.

Leanne Williams

The scientists also randomly assigned 250 of the study participants to receive one of three commonly used antidepressants or behavioral talk therapy. Patients with one subtype, which is characterized by overactivity in cognitive regions of the brain, experienced the best response to the antidepressant venlafaxine (commonly known as Effexor) compared with those who have other biotypes. Those with another subtype, whose brains at rest had higher levels of activity among three regions associated with depression and problem-solving, had better alleviation of symptoms with behavioral talk therapy. And those with a third subtype, who had lower levels of activity at rest in the brain circuit that controls attention, were less likely to see improvement of their symptoms with talk therapy than those with other biotypes.

The biotypes and their response to behavioral therapy make sense based on what they know about these regions of the brain, said Jun Ma, MD, PhD, the Beth and George Vitoux Professor of Medicine at the University of Illinois Chicago and one of the authors of the study. The type of therapy used in their trial teaches patients skills to better address daily problems, so the high levels of activity in these brain regions may allow patients with that biotype to more readily adopt new skills. As for those with lower activity in the region associated with attention and engagement, Ma said it’s possible that pharmaceutical treatment to first address that lower activity could help those patients gain more from talk therapy.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time we’ve been able to demonstrate that depression can be explained by different disruptions to the functioning of the brain,” Williams said. “In essence, it’s a demonstration of a personalized medicine approach for mental health based on objective measures of brain function.”

In another recently published study , Williams and her team showed that using fMRI brain imaging improves their ability to identify individuals likely to respond to antidepressant treatment. In that study, the scientists focused on a subtype they call the cognitive biotype of depression, which affects more than a quarter of those with depression and is less likely to respond to standard antidepressants. By identifying those with the cognitive biotype using fMRI, the researchers accurately predicted the likelihood of remission in 63% of patients, compared with 36% accuracy without using brain imaging. That improved accuracy means that providers may be more likely to get the treatment right the first time. The scientists are now studying novel treatments for this biotype with the hope of finding more options for those who don’t respond to standard antidepressants.

For example, in research published July 5 in Nature Mental Health , Williams’ team showed that transcranial magnetic stimulation was particularly effective for the cognitive biotype. The study enrolled 43 veterans, with 26 identified by fMRI as having the cognitive biotype. After 30 daily sessions of transcranial magnetic stimulation that targeted the cognitive control circuit, veterans with the cognitive biotype recovered the deficits in their brain connectivity and improved on tests of cognitive control. Most of the improvement occurred within the first five days of treatment. The findings further demonstrate the promise of using biotypes to take the guesswork out of depression treatment.

Further explorations of depression

The different biotypes also correlate with differences in symptoms and task performance among the trial participants. Those with overactive cognitive regions of the brain, for example, had higher levels of anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure) than those with other biotypes; they also performed worse on executive function tasks. Those with the subtype that responded best to talk therapy also made errors on executive function tasks but performed well on cognitive tasks.

One of the six biotypes uncovered in the study showed no noticeable brain activity differences in the imaged regions from the activity of people without depression. Williams believes they likely haven’t explored the full range of brain biology underlying this disorder — their study focused on regions known to be involved in depression and anxiety, but there could be other types of dysfunction in this biotype that their imaging didn’t capture.

Williams and her team are expanding the imaging study to include more participants. She also wants to test more kinds of treatments in all six biotypes, including medicines that haven’t traditionally been used for depression.

Her colleague Laura Hack , MD, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, has begun using the imaging technique in her clinical practice at Stanford Medicine through an experimental protocol . The team also wants to establish easy-to-follow standards for the method so that other practicing psychiatrists can begin implementing it.

“To really move the field toward precision psychiatry, we need to identify treatments most likely to be effective for patients and get them on that treatment as soon as possible,” Ma said. “Having information on their brain function, in particular the validated signatures we evaluated in this study, would help inform more precise treatment and prescriptions for individuals.”

Researchers from Columbia University; Yale University School of Medicine; the University of California, Los Angeles; UC San Francisco; the University of Sydney; the University of Texas MD Anderson; and the University of Illinois Chicago also contributed to the study.

Datasets in the study were funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01MH101496, UH2HL132368, U01MH109985 and U01MH136062) and by Brain Resource Ltd.

- Rachel Tompa Rachel Tompa is a freelance science writer.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Hope amid crisis

Psychiatry’s new frontiers

- Open access

- Published: 15 July 2024

Enhancing psychological well-being in college students: the mediating role of perceived social support and resilience in coping styles

- Shihong Dong 1 ,

- Huaiju Ge 1 ,

- Wenyu Su 1 ,

- Weimin Guan 1 ,

- Xinquan Li 1 ,

- Yan Liu 2 ,

- Qing Yu 1 ,

- Yuantao Qi 2 ,

- Huiqing Zhang 3 &

- Guifeng Ma 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 393 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

179 Accesses

Metrics details

The prevalence of depression among college students is higher than that of the general population. Although a growing body of research suggests that depression in college students and their potential risk factors, few studies have focused on the correlation between depression and risk factors. This study aims to explore the mediating role of perceived social support and resilience in the relationship between trait coping styles and depression among college students.

A total of 1262 college students completed questionnaires including the Trait Coping Styles Questionnaire (TCSQ), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), and the Resilience Scale-14 (RS-14). Common method bias tests and spearman were conducted, then regressions and bootstrap tests were used to examine the mediating effects.

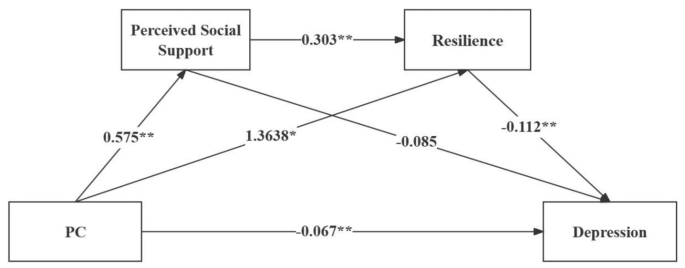

In college students, there was a negative correlation between perceived control PC and depression, with a significant direct predictive effect on depression ( β = -0.067, P < 0.01); in contrast, negative control NC showed the opposite relationship ( β = 0.057, P < 0.01). PC significantly positively predicted perceived social support ( β = 0.575, P < 0.01) and psychological resilience ( β = 1.363, P < 0.01); conversely, NC exerted a significant negative impact. Perceived social support could positively predict psychological resilience ( β = 0.303, P < 0.01), and both factors had a significant negative predictive effect on depression. Additionally, Perceived social support and resilience played a significant mediating role in the relationship between trait coping styles and depression among college students, with three mediating paths: PC/NC → perceived social support → depression among college students (-0.049/0.033), PC/NC→ resilience → depression among college students (-0.122/-0.021), and PC/NC → perceived social support → resilience → depression among college students (-0.016/0.026).

The results indicate that trait coping styles among college students not only directly predict lower depression but also indirectly influence them through perceived social support and resilience. This suggests that guiding students to confront and solve problems can alleviate their depression.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Depression is a complex mental disorder, characterized by cognitive, affective and psychosocial symptoms [ 1 , 2 ]. It is projected that by 2030, depression will rank first globally in terms of years lived with disability [ 3 , 4 ]. Depression is also one of the most common mental health issues among contemporary college students [ 5 , 6 ]. Studies have shown that the detection rate of depression among Chinese college students ranges from 23–34% [ 7 , 8 ]. Compared to non-student populations, college students have a higher prevalence of depression, and this rate seems to be increasing [ 9 ]. This vulnerable group of college students is in a unique developmental stage, facing pressures not only from life but also from the demands of academic coursework and complex interpersonal relationships, making the factors influencing depression among college students, particularly complex [ 9 , 10 ].

Exploring the mechanisms by which influencing factors affect the occurrence of depression in college students is of significant importance for early prevention [ 11 ]. Research has demonstrated that trait coping style is one of the risk factors for depression among college students. Trait coping refers to the strategies individuals employ in challenging situations, categorized into positive coping and negative coping [ 12 , 13 ]. Positive coping focuses on taking effective action and changing stressful situations, typically associated with problem-solving behaviors and regulation of positive emotions, which can help reduce the incidence of depression [ 14 ]. Conversely, negative coping is a passive approach centered around negative evaluations and emotional expression, often involving avoiding problems and social isolation, which is more likely to lead to the development of depression [ 14 ]. Research indicates that positive coping strategies are inversely correlated with depression, serving as protective factors against depression. Conversely, negative coping strategies are positively associated with depression, acting as risk factors for its onset [ 15 ].

Perceived social support refers to an individual’s subjective emotional state of feeling supported and understood by family, friends, and other sources [ 16 , 17 ]. Prior studies have shown that perceived social support can directly impact an individual’s level of depression and also have indirect effects [ 18 ]. The data indicate that social support can significantly influence coping mechanisms, with groups having higher levels of social support tended to respond more actively and positively to stress from various sources [ 19 ]. Social support is considered an important mediating factor in determining the relationship between psychological stress and health, representing an emotional experience where individuals feel supported, respected, and understood [ 16 ]. The relationship between individuals’ coping strategies and depression may be influenced by the mediating role of perceived social support [ 20 , 21 ]. In addition to this, resilience plays a role in all three.Resilience refers to the ability to adapt to stress and adversity, enhancing an individual’s psychological well-being [ 22 ]. Both coping styles and perceived social support significantly predict resilience positively [ 23 ]. For individuals with strong resilience, possessing a high level of adaptive capacity can mitigate the negative effects of stress on individuals, thereby enhancing their mental health.

In recent years, there has been a growing body of research on the prevalence of depression among college students. However, the rates of depression vary in different environments, and there is limited research on the mechanisms through which trait coping styles, perceived social support, and resilience impact depression. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the mechanisms through which positive coping styles(PC), negative coping styles(NC), perceived social support, and resilience influence depression among college students. Additionally, it seeks to analyze the mediating roles of perceived social support and resilience in this context. The goal is to provide insights into the reasons behind depression among college students under different coping strategies, aiding in timely psychological adjustment to promote the comprehensive development of the mental and physical well-being of college students.

The following assumptions were made:

Hypothesis 1

PC has a significant negative predictive effect on depression among college students. NC has a significant positive predictive effect on depression among college students.

Hypothesis 2

Perceived social support serves as a mediator between PC/NC and depression among college students.

Hypothesis 3

Resilience mediates the relationship between PC/NC and depression among college students.

Hypothesis 4

Perceived social support and psychological resilience mediate the relationship between PC/NC and depression among college students in a serial manner.

Data and methods

This is a cross-sectional study that was conducted from January through February 2024. Using the Questionnaire Star network platform, we presented the questionnaire online, which was openly accessible to college students at a university in Shandong. The average time to complete the survey was 15 min. Participation was voluntary and students were informed about the purpose of the study. Confidentiality was assured and questionnaires were submitted anonymously. A total of 1267 enrolled college students participated in the questionnaire survey. After excluding invalid questionnaires, 1262 valid questionnaires were included, resulting in an effective rate of 99.57%.

Trait coping style questionnaire

The Trait Coping Style Questionnaire (TCSQ) [ 24 ], developed by Qianjin Jiang, was utilized to assess the trait coping styles of college students. This questionnaire reflects the participants’ approaches to coping with situations, comprising a total of 20 items. It consists of two dimensions: negative coping style and positive coping style, each with 10 items. Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “definitely not” to “definitely yes,” scores were assigned from 1.00 to 5.00. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for negative coping style was 0.906 and for positive coping style was 0.786 in this study.

Depression scale

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [ 25 ] was used to assess depressive symptoms in the past two weeks. This scale consists of 9 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day,” with scores from 0 to 3. The total score ranges from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in the current study was 0.884.

Perceived Social Support Scale

The Perception Social Support Scale (PSSS) was compiled by James A.Blumenthal in 1987 and later translated and modified by Qianjin Jiang to form the Chinese version of the Zimetm Perception Social Support Scale (PSSS) [ 26 , 27 ]. PSSS comprises 12 self-assessment items rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The scale includes three dimensions: family support (items 3, 4, 8, 11), friend support (items 6, 7, 9, 12), and other support (items 1, 2, 5, 10), with a total score ranging from 12 to 84. Scores of 12–36 indicate low support, 37–60 indicate moderate support, and 61–84 indicate high support. The Cronbach’s α for this scale in the current survey was 0.968.

Resilience scale

The Resilience Scale (RS-14) [ 28 ] Chinese version consists of 14 items, each rated on a 7-point Likert scale from “not at all” to “completely,” with scores ranging from 1 to 7. The total score ranges from 14 to 98, with higher scores indicating better resilience. The Cronbach’s α for this scale in the current study was 0.925.

Statistical analysis

Data were organized and analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software. Confirmatory factor analysis was first conducted on the questionnaires. Descriptive analysis was then performed on the scores of each scale. Spearman was used to examine the relationships between trait coping styles, perceived social support, resilience, and depression. Mediation analysis was carried out using the SPSS PROCESS macro 3.4.1 software model 6 developed by Hayes, specifically designed for testing complex models. Model 6 was applied for two mediating variables, followed by the bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap method with 5000 resamples to estimate the 95% confidence interval of the mediation effect. A significant mediation effect was indicated if the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include zero. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Examination of common method bias

Systematic errors in indicator data results caused by the same data collection method or measurement environment can typically be assessed through the Harman single-factor test on 55 items in the dataset to examine common method bias. The results indicated that there were 7 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 34.84%, which was below the critical threshold of 40%. Therefore, this study may not have a significant common method bias.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The mean scores, standard deviations, and correlations of each variable are presented in Table 1 . PC ( r = -0.326, P < 0.01), resilience ( r =-0.445, P < 0.01), and perceived social support ( r =-0.405, P < 0.01) were negatively correlated with depression. PC ( r = 0.336, P < 0.01) and resilience ( r = 0.469, P < 0.01) were significantly positively correlated with perceived social support. PC was significantly positively correlated with resilience( r = 0.635, P < 0.01). NC was significantly positively correlated with depression( r = 0.322, P < 0.01) and PC( r = 0.146, P < 0.01). NC was significantly negatively correlated with perceived social support ( r =-0.325, P < 0.01).

Analysis of chain mediation effects

The chain mediation model was validated using SPSS PROCESS Model 6. Trait coping styles were considered as the independent variable, while depression among college students was treated as the dependent variable. Perceived social support and resilience were included as the mediating variables, culminating in the path model depicted in Figs. 1 and 2 .

The results of the regression analysis, as shown in Table 2 , indicated that PC could significantly predict perceived social support in a positive direction ( β = 0.575, P < 0.01). Both PC ( β = 1.363, P < 0.01) and perceived social support ( β = 0.303, P < 0.01) had significant positive predictive effects on psychological resilience. When simultaneously predicting depression using PC, perceived social support, and psychological resilience, all three exhibited significant negative predictive effects ( β = -0.067, β = -0.085, β = -0.090, P < 0.01). NC could significantly predict perceived social support in a negative direction ( β = -0.457, P < 0.01). When NC ( β = 0.191, P < 0.01) and perceived social support ( β = 0.508, P < 0.01) jointly predict psychological resilience, they both had significant positive predictive effects. When simultaneously predicting depression using NC, perceived social support, and psychological resilience, NC ( β = 0.057, P < 0.01) showed a significant positive predictive effect, while perceived social support ( β = -0.072, P < 0.01) and psychological resilience ( β = -0.112, P < 0.01) demonstrated significant negative predictive effects.

Further employing the Bootstrap sampling method, with 5000 repetitions, the significance of the mediating effects and chain mediation effects between trait coping styles and depression among college students was examined. The results indicated that the direct effects of PC/NC on depression were significant, with direct impact values of -0.067/0.057 (26.38%/60.00%). Perceived social support and psychological resilience mediated the relationship between PC/NC and depression, with this mediation encompassing three pathways: the separate mediating effect of perceived social support, with effect values of -0.049 and 0.033 respectively; the separate mediating effect of resilience, with effect values of -0.122 and − 0.021 respectively; and the serial mediating effect from perceived social support to resilience, with effect values of -0.016, -0.021, and 0.026. The 95% confidence intervals for all pathways did not include 0, indicating significant indirect effects. Therefore, the total indirect effects were − 0.187 (73.62%) and 0.038 (40.00%), showing that PC had a weaker direct effect on depression compared to NC, but a stronger indirect effect. This was illustrated in Table 3 .

Chain mediation model of perceived social support and resilience between PC and depression. ** p < 0.01

Chain mediation model of perceived social support and resilience between NC and depression. ** p < 0.01

Previous research on the associations and specific pathways among depressive symptoms, trait coping styles, perceived social support, and resilience in college students has been limited. Therefore, this study utilized a chain mediation model to examine how trait coping styles, perceived social support, and resilience influence depressive symptoms in college students. The results indicate that perceived social support and resilience not only act as separate mediators between PC/NC and depression but also exhibit a chain mediation effect.

Mechanisms of the impact of PC/NC on depression in college students

This study found that trait coping styles can significantly and negatively predict depressive symptoms in college students directly, consistent with previous research [ 29 ]. In recent years, amidst the backdrop of the pandemic, numerous studies have emerged domestically and internationally focusing on college students’ mental health from the perspective of crisis event coping [ 30 ]. These studies have predominantly concentrated on trait coping styles as a mediating variable in predicting the occurrence of depressive symptoms, with fewer studies examining the direct impact of trait coping styles on depressive symptoms. College students, being in a unique developmental stage, face challenges from various aspects and bear the pressures of academic coursework, interpersonal relationships, and future employment. Research indicates that trait coping styles are a key factor influencing mental health [ 31 ]. Implementing healthy coping techniques and interventions can help individuals overcome negative emotions caused by stress, which is an adaptive coping mechanism that assists college students in facing stress and enhancing problem-solving abilities, thus preventing or reducing the occurrence of depression. Conversely, adopting passive or avoidant coping strategies, leading to inadequate resolution of stress events, can increase psychological stress [ 14 ], thereby exerting a negative impact on the mental health of college students [ 32 ]. Therefore, trait coping styles play a negative predictive role in depressive symptoms among college students. PC was a positive predictor of depression and NC was a negative predictor of depression. This is consistent with previous studies [ 24 , 29 ].

Separate mediating effects of perceived social support and resilience

After introducing perceived social support and resilience as two mediating variables, the predictive effect of PC/NC on depressive symptoms in college students remained significant. The results show that PC can positively predict perceived social support, and NC is the opposite, consistent with previous research [ 33 ]. Trait coping styles are an important predictive factor in altering college students’ perceptions of social support and the occurrence of depression. Individuals who adopt negative coping styles tend to perceive relatively less external support. Some argue that social support plays a reverse predictive role in trait coping styles; the more social support college students receive and feel, the more likely they are to actively adopt positive coping strategies to alleviate stress, potentially due to variations in study subjects and time [ 34 ]. In this pathway, perceived social support can significantly and negatively predict depressive symptoms, aligning with previous research findings [ 35 ]. Perceived social support is considered a crucial mediating factor influencing mental health, referring to an individual’s ability to perceive support and understanding from family, friends, and others. College students with lower levels of perceived social support often feel neglected and undervalued, leading to negative evaluations and self-doubt, making them more susceptible to depression. PC/NC and perceived social support can interact and influence the occurrence of depressive symptoms in college students [ 16 ].

Research indicates that PC can significantly and positively predict resilience, with an indirect effect value of 48.03%.In this pathway, the mediating effect of resilience is more pronounced, consistent with previous studies [ 36 ]. There is a close connection between resilience and coping styles; college students who adopt positive coping strategies often exhibit stronger psychological resilience, being more willing to confront issues and seek help from others to solve problems. When facing pressures such as academic challenges, they approach them with a positive mindset, overcoming adversity [ 37 ]. It is believed that adopting positive coping strategies to address problems can enhance college students’ levels of psychological resilience [ 10 , 38 ]. Resilience can significantly and negatively predict depressive symptoms. depressive symptoms, College students with higher levels of resilience tend to define the severity of events less severely when stress events occur, resulting in lower psychological burdens and reduced likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms [ 10 ]. Additionally, when facing setbacks or stress, individuals who adopt positive coping strategies actively utilize internal and external protective factors to combat current difficulties and pressures, and employ effective emotional control to mitigate the impact, thereby enhancing their levels of psychological resilience and reducing the occurrence of depression.

Chain mediation effect of perceived social support and psychological resilience

This study elucidates that PC/NC perceived social support, and psychological resilience are independent factors influencing depressive symptoms in college students, with perceived social support and psychological resilience playing a mediating role between coping styles and depressive symptoms. The share of total indirect effect values is 73.62% and 40.00%, respectively, with the third chain path accounting for 6.30% and 27.37% of the total effect ratio, respectively. This confirms the existence of this chain mediation effect, although the chain mediation effect is not as pronounced as the individual mediation effects. Positive coping styles not only directly negatively predict depressive symptoms in college students but also exert an indirect influence on depressive symptoms through perceived social support and psychological resilience. Likewise, negative coping styles not only directly positively predict depressive symptoms in college students but also have an indirect impact on depressive symptoms through perceived social support and psychological resilience, thus demonstrating the value and significance of these two mediating variables in reducing the occurrence of depressive symptoms in college students.

Initially, adopting positive coping styles and being able to perceive social support are crucial factors influencing psychological resilience in college students. There exists a relatively stable systemic relationship between students’ social support and psychological resilience, confirming that social support can enhance individuals’ levels of psychological resilience [ 16 ]. Furthermore, coping styles can affect the occurrence of depressive symptoms from both internal and external perspectives. This is because the social support perceived by college students includes not only tangible social support resources but also their subjective perception of social support, with these two factors constituting external and internal protective factors of psychological resilience [ 39 ]. Positive coping and effective adaptation can enhance college students’ perception of social support, enabling them to mobilize personal, familial, and societal protective factors better when facing various life challenges, thereby mitigating or eliminating difficulties and suppressing the onset of depressive symptoms, whereas negative coping styles yield the opposite effect. The chain mediation proposed in this study integrates the research on perceived social support, psychological resilience, and depressive symptoms in college students, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the internal mechanisms through which coping styles influence depressive symptoms in college students. This holds significance in advocating for a proactive attitude in college students to confront and resolve difficulties and in increasing attention to the mental health of college students.

Limitations, strengths and future research

The findings of this study hold theoretical value and practical implications, offering a reference basis for improving the mental health of college students. However, there are certain limitations to consider. Firstly, the survey in this study was conducted through self-reporting, which may introduce certain biases. Future research could explore data collection through various methods. Secondly, this study employed a cross-sectional design to investigate the impact of trait coping styles, on depression among college students and its potential mechanisms. However, this research approach does not allow for causal inferences between variables, and further validation of the study’s conclusions could be achieved through longitudinal or experimental research.

In summary, this study aims to improve the mental health of college students by examining how their coping styles, along with their perceived social support and psychological resilience, affect depressive symptoms. The research analyzes the connections between these factors and suggests that positive coping styles may help prevent depression. However, the study has its limitations and future research should use long-term experiments to better understand these relationships. Since depression in college students can be influenced by many factors, future studies should also consider additional variables and use a mix of experimental and longitudinal approaches to more clearly understand how to reduce depression in this group.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

Trait Coping Style Questionnaire

Positive coping styles

Negative coping styles

Resilience Scale

Platania GA, Savia Guerrera C, Sarti P, et al. Predictors of functional outcome in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder: a dynamic network approach to identify distinct patterns of interacting symptoms[J]. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(2):e0276822.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guerrera CS, Platania GA, Boccaccio FM, et al. The dynamic interaction between symptoms and pharmacological treatment in patients with major depressive disorder: the role of network intervention analysis[J]. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):885.

Liu Y, Chen J, Chen K, et al. The associations between academic stress and depression among college students: a moderated chain mediation model of negative affect, sleep quality, and social support[J]. Acta Psychol. 2023;239:104014.

Article Google Scholar

Gao L, Xie Y, Jia C, et al. Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15897.

Naja WJ, Kansoun AH, Haddad RS. Prevalence of Depression in Medical students at the Lebanese University and exploring its correlation with Facebook Relevance: a Questionnaire Study[J]. JMIR Res Protocols. 2016;5(2):e96.

Brenneisen Mayer F, Souza Santos I, Silveira PSP, et al. Factors associated to depression and anxiety in medical students: a multicenter study[J]. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):282.

Liu Y, Zhang N, Bao G, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:196–208.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Moutinho ILD, Maddalena N, D C P, Roland RK, et al. Depression, stress and anxiety in medical students: a cross-sectional comparison between students from different semesters[J]. Volume 63. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira; 2017. pp. 21–8. 1.

Acharya L, Jin L, Collins W. College life is stressful today – emerging stressors and depressive symptoms in college students[J]. J Am Coll Health. 2018;66(7):655–64.

Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, et al. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students[J]. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(3):391–400.

Zvauya R, Oyebode F, Day EJ, et al. A comparison of stress levels, coping styles and psychological morbidity between graduate-entry and traditional undergraduate medical students during the first 2 years at a UK medical school[J]. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):93.

Undheim AM, Sund AM. Associations of stressful life events with coping strategies of 12–15-year-old Norwegian adolescents[J]. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(8):993–1003.

Lau Y, Wang Y, Kwong DHK, et al. Are different coping styles Mitigating Perceived stress Associated with depressive symptoms among pregnant women? Are different coping styles Mitigating Perceived stress Associated with depressive symptoms among pregnant women?[J]. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2016;52(2):102–12.

Ding Y, Yang Y, Yang X, et al. The Mediating Role of coping style in the relationship between Psychological Capital and Burnout among Chinese Nurses[J]. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0122128.

Gandzha IM. [Immune disorders in internal diseases and the ways for their correction][J]. Vrach Delo, 1978(7): 14–9.

Howard S, Creaven AM, Hughes BM, et al. Perceived social support predicts lower cardiovascular reactivity to stress in older adults[J]. Biol Psychol. 2017;125:70–5.

Barrera M. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models[J]. Am J Community Psychol. 1986;14(4):413–45.

Xin M, Yang C, Zhang L, et al. The impact of perceived life stress and online social support on university students’ mental health during the post-COVID era in Northwestern China: gender-specific analysis[J]. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):467.

Sun J, Harris K, Vazire S. Is well-being associated with the quantity and quality of social interactions?[J]. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2020;119(6):1478–96.

Wang J, Chen Y, Chen H, et al. The mediating role of coping strategies between depression and social support and the moderating effect of the parent–child relationship in college students returning to school: during the period of the regular prevention and control of COVID-19[J]. Front Psychol. 2023;14:991033.

Ball S, Bax A. Self-care in Medical Education: effectiveness of health-habits interventions for First-Year Medical Students[J]. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):911–7.

Howe A, Smajdor A, Stöckl A. Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training[J]. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):349–56.

Louise Duncan D. What the COVID-19 pandemic tells us about the need to develop resilience in the nursing workforce[J]. Nurs Manag. 2020;27(3):22–7.

Google Scholar

Luo Y, Wang H. Correlation research on psychological health impact on nursing students against stress, coping way and social support[J]. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(1):5–8.

Luo Mming, Hao M, Li Xhuan, et al. Prevalence of depressive tendencies among college students and the influence of attributional styles on depressive tendencies in the post-pandemic era[J]. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1326582.

Zhang Y, Jia Y, MuLaTiHaJi M, et al. A cross-sectional mental-health survey of Chinese postgraduate students majoring in stomatology post COVID-19 restrictions[J]. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1376540.

Blumenthal JA, Burg MM, Barefoot J, et al. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease.:[J]. Psychosom Med. 1987;49(4):331–40.

Quintiliani L, Sisto A, Vicinanza F, et al. Resilience and psychological impact on Italian university students during COVID-19 pandemic. Distance learning and health[J]. Volume 27. Psychology, Health & Medicine; 2022. pp. 69–80. 1.

Shao R, He P, Ling B, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students[J]. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):38.

Riedel B, Horen SR, Reynolds A, et al. Mental Health disorders in Nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications and coping Strategies[J]. Front Public Health. 2021;9:707358.

Faisal-Cury A, Savoia MG, Menezes PR. Coping style and depressive symptomatology during pregnancy in a private setting Sample[J]. Span J Psychol. 2012;15(1):295–305.

Platania GA, Varrasi S, Guerrera CS, et al. Impact of stress during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a study on dispositional and behavioral dimensions for supporting evidence-based targeted Strategies[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(3):330.

Xu Y, Zheng Q, Jiang X, et al. Effects of coping on nurses’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating role of social support and psychological resilience[J]. Nurs Open. 2023;10(7):4619–29.

Kassam S. Understanding experiences of Social Support as Coping resources among immigrant and Refugee women with Postpartum Depression: an Integrative Literature Review[J]. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40(12):999–1011.

Xu J, Wei Y. Social Support as a moderator of the relationship between anxiety and depression: an empirical study with adult survivors of Wenchuan Earthquake[J]. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e79045.

Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The Construct of Resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future Work[J]. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–62.

Lee SH, Cho SJ. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depressive Disorders[M]//, Kim YK. Major Depressive Disorder: Vol. 1305. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021: 295–310.

Thompson G, McBride RB, Hosford CC, et al. Resilience among medical students: the role of coping style and social Support[J]. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(2):174–82.

Murphy J, McGrane B, White RL, et al. Self-Esteem, meaningful experiences and the Rocky Road—contexts of physical activity that impact Mental Health in Adolescents[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15846.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to provide our extreme thanks and appreciation to all students who participated in our study.

This work was financially supported by the National Food Safety Risk Center Joint Research Program [grant number (LH2022GG06)] and the Weifang Medical College Teaching Reform Program (2023YBC008).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health, Shandong Second Medical University, No. 7166, Baotong West Street, Weicheng District, Weifang City, 261053, China

Shihong Dong, Huaiju Ge, Wenyu Su, Weimin Guan, Xinquan Li, Qing Yu & Guifeng Ma

Shandong Cancer Research Institute (Shandong Tumor Hospital), No.440, Jiyan Road, Huaiyin District, Jinan, 250117, China

Yan Liu & Yuantao Qi

The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong Second Medical University (Weifang People’s Hospital), No.151 Guangwen Street, Weicheng District, Weifang City, 261041, China

Huiqing Zhang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SD and GM conceived and designed the study. HG, WS, WG, and YL undertook the data collection and analysis. SD, QY, YQ, XLand HZ drafted the manuscript. SD and GM reviewed the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Huiqing Zhang or Guifeng Ma .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shandong Second Medical University and written informed consent was required from all participants. Participation was voluntary and students were informed about the purpose of the study. Confidentiality was assured and questionnaires were submitted anonymously.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dong, S., Ge, H., Su, W. et al. Enhancing psychological well-being in college students: the mediating role of perceived social support and resilience in coping styles. BMC Psychol 12 , 393 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01902-7

Download citation

Received : 04 March 2024

Accepted : 12 July 2024

Published : 15 July 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01902-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- College students

- Perceived social support

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Outcomes are estimated from bivariate and multivariable generalized estimating equation models. aOR, indicates adjusted odds ratio; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale; whiskers, 95% CIs.

eTable 1. Survey Instruments

eTable 2. Prevalence of Exposure Over Time

eTable 3. Prevalence of Outcomes Over Time by Exposure Group

eTable 4. E-Value Calculation for Association Between Puberty Blockers or Gender-Affirming Hormones and Mental Health Outcomes

eTable 5. Examining Association Between Puberty Blockers or Gender-Affirming Hormones and Mental Health Outcomes Separately

eTable 6. Bivariate Model Restricted to Youths Ages 13 to 17 Years

eTable 7. Multivariable Model Restricted to 90 Youths Ages 13 to 17 Years

eTable 8. Sensitivity Analyses using Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item Scale Score of 10 or Greater for Moderate to Severe Depression

eFigure 1. Schematic of Generalized Estimating Equation Model

eFigure 2. Association Between Receipt of Gender-Affirming Hormones or Puberty Blockers and Mental Health Outcomes

eReferences

- Medical Groups Defend Patient-Physician Relationship and Access to Adolescent Gender-Affirming Care JAMA Medical News & Perspectives April 19, 2022 This Medical News article discusses physicians’ advocacy to protect patients and the patient-physician relationship amid efforts by politicians to limit access or criminalize gender-affirming care. Bridget M. Kuehn, MSJ

- As Laws Restricting Health Care Surge, Some US Physicians Choose Between Fight or Flight JAMA Medical News & Perspectives June 13, 2023 In this Medical News article, 13 physicians and health care experts spoke with JAMA about the increasing efforts to criminalize evidence-based medical care in the US. Melissa Suran, PhD, MSJ

- Data Errors in eTables 2 and 3 JAMA Network Open Correction July 26, 2022

- Improving Mental Health Among Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth JAMA Network Open Invited Commentary February 25, 2022 Brett Dolotina, BS; Jack L. Turban, MD, MHS

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Tordoff DM , Wanta JW , Collin A , Stepney C , Inwards-Breland DJ , Ahrens K. Mental Health Outcomes in Transgender and Nonbinary Youths Receiving Gender-Affirming Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Mental Health Outcomes in Transgender and Nonbinary Youths Receiving Gender-Affirming Care

- 1 Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle

- 2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle

- 3 School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle

- 4 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Department of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington

- 5 University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, Rady Children's Hospital

- 6 Division of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington

- Invited Commentary Improving Mental Health Among Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth Brett Dolotina, BS; Jack L. Turban, MD, MHS JAMA Network Open

- Medical News & Perspectives Medical Groups Defend Patient-Physician Relationship and Access to Adolescent Gender-Affirming Care Bridget M. Kuehn, MSJ JAMA

- Medical News & Perspectives As Laws Restricting Health Care Surge, Some US Physicians Choose Between Fight or Flight Melissa Suran, PhD, MSJ JAMA

- Correction Data Errors in eTables 2 and 3 JAMA Network Open

Question Is gender-affirming care for transgender and nonbinary (TNB) youths associated with changes in depression, anxiety, and suicidality?

Findings In this prospective cohort of 104 TNB youths aged 13 to 20 years, receipt of gender-affirming care, including puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormones, was associated with 60% lower odds of moderate or severe depression and 73% lower odds of suicidality over a 12-month follow-up.

Meaning This study found that access to gender-affirming care was associated with mitigation of mental health disparities among TNB youths over 1 year; given this population's high rates of adverse mental health outcomes, these data suggest that access to pharmacological interventions may be associated with improved mental health among TNB youths over a short period.

Importance Transgender and nonbinary (TNB) youths are disproportionately burdened by poor mental health outcomes owing to decreased social support and increased stigma and discrimination. Although gender-affirming care is associated with decreased long-term adverse mental health outcomes among these youths, less is known about its association with mental health immediately after initiation of care.

Objective To investigate changes in mental health over the first year of receiving gender-affirming care and whether initiation of puberty blockers (PBs) and gender-affirming hormones (GAHs) was associated with changes in depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

Design, Setting, and Participants This prospective observational cohort study was conducted at an urban multidisciplinary gender clinic among TNB adolescents and young adults seeking gender-affirming care from August 2017 to June 2018. Data were analyzed from August 2020 through November 2021.

Exposures Time since enrollment and receipt of PBs or GAHs.

Main Outcomes and Measures Mental health outcomes of interest were assessed via the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scales, which were dichotomized into measures of moderate or severe depression and anxiety (ie, scores ≥10), respectively. Any self-report of self-harm or suicidal thoughts over the previous 2 weeks was assessed using PHQ-9 question 9. Generalized estimating equations were used to assess change from baseline in each outcome at 3, 6, and 12 months of follow-up. Bivariate and multivariable logistic models were estimated to examine temporal trends and investigate associations between receipt of PBs or GAHs and each outcome.

Results Among 104 youths aged 13 to 20 years (mean [SD] age, 15.8 [1.6] years) who participated in the study, there were 63 transmasculine individuals (60.6%), 27 transfeminine individuals (26.0%), 10 nonbinary or gender fluid individuals (9.6%), and 4 youths who responded “I don’t know” or did not respond to the gender identity question (3.8%). At baseline, 59 individuals (56.7%) had moderate to severe depression, 52 individuals (50.0%) had moderate to severe anxiety, and 45 individuals (43.3%) reported self-harm or suicidal thoughts. By the end of the study, 69 youths (66.3%) had received PBs, GAHs, or both interventions, while 35 youths had not received either intervention (33.7%). After adjustment for temporal trends and potential confounders, we observed 60% lower odds of depression (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.40; 95% CI, 0.17-0.95) and 73% lower odds of suicidality (aOR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.11-0.65) among youths who had initiated PBs or GAHs compared with youths who had not. There was no association between PBs or GAHs and anxiety (aOR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.41, 2.51).

Conclusions and Relevance This study found that gender-affirming medical interventions were associated with lower odds of depression and suicidality over 12 months. These data add to existing evidence suggesting that gender-affirming care may be associated with improved well-being among TNB youths over a short period, which is important given mental health disparities experienced by this population, particularly the high levels of self-harm and suicide.

Transgender and nonbinary (TNB) youths are disproportionately burdened by poor mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation and attempts. 1 - 5 These disparities are likely owing to high levels of social rejection, such as a lack of support from parents 6 , 7 and bullying, 6 , 8 , 9 and increased stigma and discrimination experienced by TNB youths. Multidisciplinary care centers have emerged across the country to address the health care needs of TNB youths, which include access to medical gender-affirming interventions, such as puberty blockers (PBs) and gender-affirming hormones (GAHs). 10 These centers coordinate care and help youths and their families address barriers to care, such as lack of insurance coverage 11 and travel times. 12 Gender-affirming care is associated with decreased rates of long-term adverse outcomes among TNB youths. Specifically, PBs, GAHs, and gender-affirming surgeries have all been found to be independently associated with decreased rates of depression, anxiety, and other adverse mental health outcomes. 13 - 16 Access to these interventions is also associated with a decreased lifetime incidence of suicidal ideation among adults who had access to PBs during adolescence. 17 Conversely, TNB youths who present to care later in adolescence or young adulthood experience more adverse mental health outcomes. 18 Despite this robust evidence base, legislation criminalizing and thus limiting access to gender-affirming medical care for minors is increasing. 19 , 20

Less is known about the association of gender-affirming care with mental health outcomes immediately after initiation of care. Several studies published from 2015 to 2020 found that receipt of PBs or GAHs was associated with improved psychological functioning 21 and body satisfaction, 22 as well as decreased depression 23 and suicidality 24 within a 1-year period. Initiation of gender-affirming care may be associated with improved short-term mental health owing to validation of gender identity and clinical staff support. Conversely, prerequisite mental health evaluations, often perceived as pathologizing by TNB youths, and initiation of GAHs may present new stressors that may be associated with exacerbation of mental health symptoms early in care, such as experiences of discrimination associated with more frequent points of engagement in a largely cisnormative health care system (eg, interactions with nonaffirming pharmacists to obtain laboratory tests, syringes, and medications). 25 Given the high risk of suicidality among TNB adolescents, there is a pressing need to better characterize mental health trends for TNB youths early in gender-affirming care. This study aimed to investigate changes in mental health among TNB youths enrolled in an urban multidisciplinary gender clinic over the first 12 months of receiving care. We also sought to investigate whether initiation of PBs or GAHs was associated with depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

This cohort study received approval from the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. For youths younger than age 18 years, caregiver consent and youth assent was obtained. For youths ages 18 years and older, youth consent alone was obtained. The 12-month assessment was funded via a different mechanism than other survey time points; thus, participants were reconsented for the 12-month survey. The study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline.

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study of TNB youths seeking care at Seattle Children’s Gender Clinic, an urban multidisciplinary gender clinic. After a referral is placed or a patient self-refers, new patients, their caregivers, or patients with their caregivers are scheduled for a 1-hour phone intake with a care navigator who is a licensed clinical social worker. Patients are then scheduled for an appointment at the clinic with a medical provider.

All patients who completed the phone intake and in-person appointment between August 2017 and June 2018 were recruited for this study. Participants completed baseline surveys within 24 hours of their first appointment and were invited to complete follow-up surveys at 3, 6, and 12 months. Youth surveys were used to assess most variables in this study; caregiver surveys were used to assess caregiver income. Participation and completion of study surveys had no bearing on prescribing of PBs or GAHs.

We assessed 3 internalizing mental health outcomes: depression, generalized anxiety, and suicidality. Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9), and anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7). We dichotomized PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores into measures of moderate or severe depression and anxiety (ie, scores ≥10). 26 , 27 Self-harm and suicidal thoughts were assessed using PHQ-9 question 9 (eTable 1 in the Supplement ).

Participants self-reported if they had ever received GAHs, including estrogen or testosterone, or PBs (eg, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues) on each survey. We conducted a medical record review to capture prescription of androgen blockers (eg, spironolactone) and medications for menstrual suppression or contraception (ie, medroxyprogesterone acetate or levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device) during the study period.

We a priori considered potential confounders hypothesized to be associated with our exposures and outcomes of interest based on theory and prior research. Self-reported gender was ascertained on each survey using a 2-step question that asked participants about their current gender and their sex assigned at birth. If a participant’s self-reported gender changed across surveys, we used the gender reported most frequently by a participant (3 individuals identified as transmasculine at baseline and as nonbinary on all follow-up surveys). We collected data on self-reported race and ethnicity (available response options were Arab or Middle Eastern; Asian; Black or African American; Latinx; Native American, American Indian, or Alaskan Native or Native Hawaiian; Pacific Islander; and White), age, caregiver income, and insurance type. Race and ethnicity were assessed as potential covariates owing to known barriers to accessing gender-affirming care among transgender youth who are members of minority racial and ethnic groups. For descriptive statistics, Asian and Pacific Islander groups were combined owing to small population numbers. We included a baseline variable reflecting receipt of ongoing mental health therapy other than for the purpose of a mental health assessment to receive a gender dysphoria diagnosis. We included a self-report variable reflecting whether youths felt their gender identity or expression was a source of tension with their parents or guardians. Substance use included any alcohol, marijuana, or other drug use in the past year. Resilience was measured by the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) 10-item score developed to measure change in an individual’s state resilience over time. 28 Resilience scores were dichotomized into high (ie, ≥median) and low (ie, <median). Prior studies of young adults in the US reported mean CD-RISC scores ranging from 27.2 to 30.1. 29 , 30

We used generalized estimating equations to assess change in outcomes from baseline at each follow-up point (eFigure 1 in the Supplement ). We used a logit link function to estimate adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for the association between variables and each mental health outcome. We initially estimated bivariate associations between potential confounders and mental health outcomes. Multivariable models included variables that were statistically significant in bivariate models. For all outcomes and models, statistical significance was defined as 95% CIs that did not contain 1.00. Reported P values are based on 2-sided Wald test statistics.

Model 1 examined temporal trends in mental health outcomes, with time (ie, baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months) modeled as a categorical variable. Model 2 estimated the association between receipt of PBs or GAHs and mental health outcomes adjusted for temporal trends and potential confounders. Receipt of PBs or GAHs was modeled as a composite binary time-varying exposure that compared mean outcomes between participants who had initiated PBs or GAHs and those who had not across all time points (eTable 2 in the Supplement ). All models used an independent working correlation structure and robust standard errors to account for the time-varying exposure variable.

We performed several sensitivity analyses. Because our data were from an observational cohort, we first considered the degree to which they were sensitive to unmeasured confounding. To do this, we calculated the E-value for the association between PBs or GAHs and mental health outcomes in model 2. The E-value is defined as the minimum strength of association that a confounder would need to have with both exposure and outcome to completely explain away their association (eTable 4 in the Supplement ). 31 Second, we performed sensitivity analyses on several subsets of youths. We separately examined the association of PBs and GAHs with outcomes of interest, although we a priori did not anticipate being powered to detect statistically significant outcomes owing to our small sample size and the relatively low proportion of youths who accessed PBs. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using the Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item scale (PHQ-8), in which the PHQ-9 question 9 regarding self-harm or suicidal thoughts was removed, given that we analyzed this item as a separate outcome. Lastly, we restricted our analysis to minor youths ages 13 to 17 years because they were subject to different laws and policies related to consent and prerequisite mental health assessments. We used R statistical software version 3.6.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing) to conduct all analyses. Data were analyzed from August 2020 through November 2021.

A total of 169 youths were screened for eligibility during the study period, among whom 161 eligible youths were approached. Nine youths or caregivers declined participation, and 39 youths did not complete consent or assent or did not complete the baseline survey, leaving a sample of 113 youths (70.2% of approached youths). We excluded 9 youths aged younger than 13 years from the analysis because they received different depression and anxiety screeners. Our final sample included 104 youths ages 13 to 20 years (mean [SD] age, 15.8 [1.6] years). Of these individuals, 84 youths (80.8%), 84 youths, and 65 youths (62.5%) completed surveys at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively.

Our cohort included 63 transmasculine youths (60.6%), 27 transfeminine youths (26.0%), 10 nonbinary or gender fluid youths (9.6%), and 4 youths who responded “I don’t know” or did not respond to the gender identity question on all completed questionnaires (3.8%) ( Table 1 ). There were 4 Asian or Pacific Islander youths (3.8%), 3 Black or African American youths (2.9%); 9 Latinx youths (8.7%); 6 Native American, American Indian, or Alaskan Native or Native Hawaiian youths (5.8%); 67 White youths (64.4%); and 9 youths who reported more than 1 race or ethnicity (8.7%). Race and ethnicity data were missing for 6 youth (5.8%).