145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best aristotle topic ideas & essay examples, 👍 good essay topics on aristotle, 💡 most interesting aristotle topics to write about, ❓ questions about aristotle.

- Plato and Aristotle on Literature Compare & Contrast Essay The controversy over the effects of literature has made the great philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, to differ in their perceptions of the literature impacts on the society.

- Plato and Aristotle’s Views of Virtue in Respect to Education Arguably, Plato and Aristotle’s views of education differ in that Aristotle considers education as a ‘virtue by itself’ that every person must obtain in order to have ‘happiness and goodness in life’, while Plato advocates […]

- Philosophy: Plato’s Republic Versus Aristotle’s Politics Plato as well turns off the partition amid the private and the public and he contends for common kids and wives for the guardians in a bid to create a society amongst the rulers of […]

- Compare and Contrast: Plato and Aristotle Essay Aristotle was a “the son of a renowned physician from Thrace” and he began his philosophy studies at the Plato’s academy.

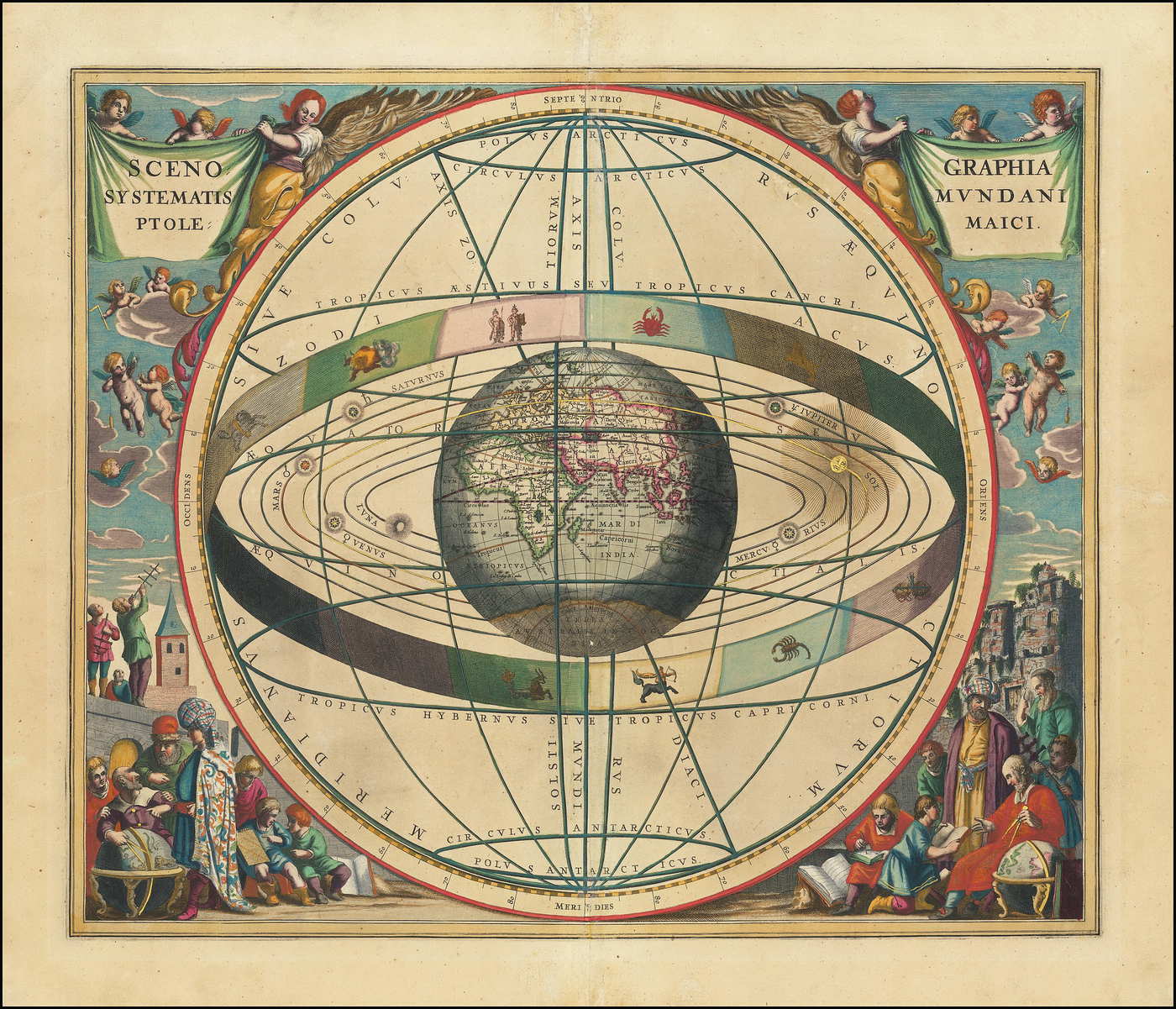

- Classical Physics: Aristotle, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton Aristotle posited that the universe consists of two parts: the terrestrial and the celestial regions and that in Earth, all bodies were made up of a mixture of four types of matter: earth, water, air, […]

- Aristotle vs. Socrates: The Main Difference in the Concept of Virtue One of the main principles on which the ethical school is based is the notion of virtue as the representation of the moral perfectness of a man.

- Aristotle’s Views on Women Before the Greek physicians and philosophers of the Classical Age took up the question of the nature of women, the Greeks had serious attitudes toward women as revealed in their literature.

- Plato vs. Aristotle: Political Philosophy Compare and Contrast Essay Plato went further to associate all the parts of the soul to parts of the body with reason connected to the head, will connected to the heart and appetite connected to the abdomen and sensory […]

- Plato on Death: Comparison With Aristotle Afterlife – Essay on Life After Death Philosophy On the other hand, religion has maintained that the soul is immortal and survives the death of the body. Plato argued that the soul is immortal and therefore survives the death of the body.

- Conflict Between Aristotle and Copernicus Copernicus continued his research and developed a new model of the universe which contradicted Aristotle’s paradigm since the Earth was not the centre, but one of the planets moving around the Sun.

- Epistemologies of Plato and Aristotle It is also worth mentioning the Allegory of the Cave, in which Plato explains the relationship between people and the world of the Forms.

- “Man is a Political Animal” by Aristotle This is based on the fact that the philosophical ideas expressed by these scholars have proven to be greatly important in offering guidance to various facets of life-like cultural, social, political, and economic endeavors In […]

- Application of Aristotle’s Golden Mean The doctrine of the golden mean is a request for a realistic moral axiom. The word “virtue” is used in some cases to denote a personal quality and, in others, as a generalized indicator of […]

- Aristotle’s and Plato’s Views on Rhetoric One of the points that Plato expresses in this philosophical work is that rhetoric should be viewed primarily as the “artificer of persuasion”. This is one of the similarities that can be distinguished.

- Othello: A Tragic Hero Through the Prism of Aristotle’s Definition According to him, the prerequisite of a tragedy revolves around the plot of the play. Othello, who is the main character, is a perfect example of a tragic hero.

- Aristotle, His Life and Philosophical Ideas Later on at the age of eighteen, he moved to Athens to study and this became his home for the next twenty years, after which he moved to Asia after the death of Plato where […]

- Tragic Hero in Aristotle’s “Poetics” According to Aristotle, the tragic error is the main manifestation of a tragic hero and it sets out the basis of his fate.

- Impact on the Development of Natural Science a Aristotle’s Book “Physics” From Aristotle’s perspective, to know the purpose of nature is the most essential task of a philosopher and his strategies should be subjected to this task.

- Philosophy: Aristotle on Moral Virtue Both virtue and vice build one’s character and therefore can contribute to the view of happiness. Therefore, character education leads to happiness that is equal to the amount of wisdom and virtue.

- The Soul Ideas by Aristotle Their organization is such that the top in the rank consists of all properties of the one at the bottom. The rational soul’s ability to reason that is not in the other types of souls.

- Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle However, the fact that there are many actions that people engage in, Aristotle argues that their ends are countless. Aristotle concludes that happiness is the key principle that causes people to practice virtues such as […]

- Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” and Aristotle’s “High-Minded Man” The concept of a High-Minded man is close to Aristotle’s understanding of success and the contribution of different virtues to an individual’s happiness.

- Aristotle’s Notion of Time and Motion It is also pertinent that the concept of Time is comprehended in relation to the concept of Motion. In an analysis of the nature of Time, it is most relevant to remember that Aristotle was […]

- Aristotle’s Concept of Happiness Aristotle’s concept of happiness is an expression of virtue that is similar to the flow state, happiness is a combination of the baseline level where basic needs are fulfilled and a broader area managed by […]

- Aristotle’s Virtue Theory vs. Buddha’s Middle Path The purpose of this paper is to review each of the two theories and develop a comparison between them. This term is in contrast to the paths of extremities described by eternalism and annihilationism that […]

- Ethical Decision-Making: Aristotle on the Sources of the Ethical Life In that way, the Nicomachean and Eudemian Ethics, as well as Magna Moralia make up the central elements of Aristotle’s wise decision-making. The Nicomachean Ethics work emphasizes the role of achieving one main aim in […]

- Greek Philosophies of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle It is argued that the origin of philosophy as a discipline owes its origin to the contribution of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle.”Socrates’ contribution to the love of wisdom was manifested by the belief that philosophy […]

- Views on Writing Style by Plato, Aristotle and Dante In the end of a dialogue or a debate, the truth is supposed to emerge from the clash of the two opinions, and the defeated one is morally obliged to accept the force of a […]

- Significance of Emotions in Aristotle’s Philosophy Additionally, the philosopher distinguishes two moralities, each with its interpretation of the cognitive role of emotions: a civic morality of judicial process in the Nicomachean Ethics and a contemplative ethics of theoretical study in Politics.

- Confucius, Plato, and Aristotle: Views on Society In the video, it is highlighted that both Plato and Confucius shared a commitment to reason and the value of the state.

- Philosophers: Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Marx The philosophical dilemma is how to do it, because in the overwhelming majority of cases, a human being is driven by the desire.

- Epicurus and Aristotle Philosophical Views on Emotions The two philosophers studied emotions to determine some of the common causes of this mental state, and the events that take place in the mind before one becomes emotional.

- Nature of Motion According To Lucretius and Aristotle Galileo utilized a number of scientific techniques to prove to the church that the earth was not the center of the universe.

- Plato and Aristotle: Criticisms of Democracy To speak of it in our present time, there are only a few people who are given the power of ‘sound judgement about what is right and what is wrong’ and should have the power […]

- Comparison of Plato’s and Aristotle’s Approaches to the Nature of Reality In contrast to Plato, Aristotle asserted that the senses were necessary for accurately determining reality and that they could not be used to deceive a person. Aristotle and Plato both considered that thoughts were superior […]

- Observation and Theory in Aristotle’s Scientific Practice Aristotle focuses on the distinction between the unobservable and observables, the content and structure of observation reports, and the epistemic importance of observational evidence for the theories he aims to access.

- Aristotle’s Ethical Theory and Nursing Therefore, the actions of an individual determine his happiness and the aspect of what is ethically good. This theory is directly related to the nursing professional code of ethics as indicated in the provisions of […]

- Aristotle’s and Freud’s Motivational Theories The efficient cause is the trigger that causes a person to behave in a certain way. These biological instincts are the source of mental or psychic energy that makes human behavior and that it is […]

- According to Aristotle, Is the Good Citizen the Same as the Good Human Being?? Why or Why Not?? Anticipating differentiation of human rights and the rights of citizen, issued in the corresponding Declaration of the period of the French revolution of the end of XVIII century, Aristotle is interested by a question – […]

- Morality and Politics: Aristotle and Machiavelli For a government to be effective, there must be a set of morals and virtues in place to ensure the people are happy.

- Being as Being: Aristotle vs. Aquinas The philosophical concept of being as being is concerned with the notion of existence, more specifically, that of the thing in and of itself.

- Syllogism and Enthymeme in Aristotle’s Rhetoric One of the implications of syllogism to audiences is in regards to the possibility of creating offensive conclusions from an argument’s statements.

- Classical Leadership Style and Aristotle’s Perspective He supported the ideas of Plato that the philosopher king has to be given a chance to exercise power while the soldiers were to provide the much-needed support by ensuring the citizens followed the law.

- Aristotle’s Ideologies Application in Practices The ideologies of philosophers have influenced the world and changed the perception and attitudes of people toward various issues. The peculiarity and popularity of Aristotle’s philosophy of life makes it easy for it to be […]

- Philosophy of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle Logic as understood by Socrates was to some extent influenced by the Pythagoreans since he practiced the dialectic methods in investigating the objectivity and authority of the different propositions.

- Aristotle’s Understanding of Happiness If happiness is “wholeness”, then for a person to become happy, it is necessary to become “whole”. Thus, all a person has to do to become whole is lower goods.

- “Nicomachean Ethics” and “Politics” by Aristotle In his works, Aristotle enunciates that the meaning of being a good citizen is relative to the institution that one is a citizen of.

- “The Rhetoric & Poetics of Aristotle” Book This is necessary to feed more meaning to the language used and contributes to the ability of rhetoric in interpersonal communication. Human interaction is a continuous communication and going back and forth in the rhetoric […]

- Aristotle’s Views on Intellect and Soul However, Aristotle insisted that parts of the intellect may operate independent of the soul, in opposition to theorists such as Xenocrates and Plato.

- Aristotle’s View on the Concept of Logic Thus, it was shown that logic is not just a specific doctrine of specific things or terms, but the science of the laws of syllogisms, such as modus ponens or modus tollens, expressed in variables. […]

- The Concept of Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics The essence of Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean is that virtue lies in between two extremes, none of which is virtuous on its own.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Works and Their Effects The first insight from these philosophical writings that shifted my viewpoint about this field was the distinctive role of the end goal and action in Plato’s and Aristotle’s works.

- The Bell Experience From Aristotle’s Perspective First, it is important for an idea to make sense in the minds of the audience. The idea of playing in the subway made sense to both Bell and the people.

- Aristotle’s View of Ethics and Happiness Aristotle guarantees that to find the human great, we should recognize the capacity of an individual. He set forth the thought that joy is a delight in magnificence and great.

- Exegetical Paper on Aristotle: Meaning of Happiness It is in the balance, according to Aristotle, that the completeness of the human personality lies, and only through balance can a person find true self-satisfaction.

- Aristotle’s Philosophy and Views on Ethics In contrast, Aristotle believed that the purpose of ethics lies beyond the knowledge of what is good or evil, but rather focuses on the application and practice of the theory.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Concepts of Political Theory In The Republic by Plato and The Politics by Aristotle, two unique originations of the state, equity, and political investment introduce themselves.

- Aristotle’s Account of Pleasure Since Aristotle is trying to discern the goal of human life, he is inclined to think that pleasure is not a chief good.

- Aristotle’s and Socrates’ Account of Virtue This is manifested in their teachings where Aristotle speaks of virtue as finding a balance between two extremes while Socrates says that virtue is the desire for one to do well in one’s life.

- Ancient Philosophy. Aristotle and Seneca on Anger Though there are conditions when anger is beneficial and useful, such as the feeling of anger that inspires the soldiers to fight abandoning hesitation and fear, Aristotle believes that the emotion of anger is constantly […]

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Views on Oedipus People in the Oedipus play lived in the dark of the unknown meaning of the riddle; until Oedipus answered the riddle.

- Plato, Aristotle and Socrates: Knowledge and Government It appears that Socrates believed in an intellectual aristocracy, where those who had more education and had proven themselves in sophistry the “Socratic method” of exchange and analysis of ideas as a path to all […]

- Argument Between Philosophy Aristotle and Philosophy Locke Aristotle considers human beings to possess the understanding of these differences and apply them in their writings as well as conversations.

- Aristotle’s Influence on History of Rhetoric: Treatise Rhetoric and the Concept of the Rhetorical Triangle Aristotle has written works in a number of subjects, such as ethics, poetry, politics, music, biology, physics, etc, but among these, his contributions into rhetoric are the most valuable; within this field, Aristotle is known […]

- The Theme of Slavery in Aristotle’s “Politics” He notes that the fundamental part of an association is the household that is comprised of three different kinds of relationships: master to slave, husband to wife, and parents to their children.

- Aristotle, Selections From The Politics. Book I The growth of the movement towards the formation of states is, however, a gradual one; it is continuous, from the sixteenth century to our day, and while, throughout this period, and in almost every country […]

- Aristotle’s – The Ethics of Virtue Ethics is not a theory of discipline since our inquiry as to what is good for human beings is not just gathering knowledge, but to be able to achieve a unique state of fulfillment in […]

- Political Science: Aristotle’s View on Human Nature A citizen, for Aristotle, is an individual who has the capacity and the right to engage in the governance of a “polies”.

- Plato’s, Aristotle’s, Petrarch’s Views on Education To begin with, Plato believed that acquisition of knowledge was the way to being virtuous in life but he tended to differ with philosophers like Aristotle stating that education to be acquired from the natural […]

- Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics Analysis When faced with the option of an apple of a muffin, a good person would choose the apple, because the part of the soul that desired the muffin would be controlled by self-control, the part […]

- Aristotle on Practical vs. Theoretical Knowledge The second argument that should be discussed in Aristotle’s view of the idea of pleasure as the way to meet the key function of a person.

- Aristotle: Natural Changes and His Theory of Form The form of an object is the arrangement of the comprising components making up the object in focus. This is the counterpart of the subjects of predication in the Categories.

- Plato and Aristotle Thoughts on Politics Aristotle emphasized that the lawgiver and the politician occupied the constitution and the state wholly and defined a citizen as one who had the right to deliberate or participate in the matters of the judicial […]

- Aristotle and His Definition of Happiness The best taste a person can have in his life is happiness because of success. But in my point of view, happiness is the main feeling that comes from the success of any useful act […]

- Aristotle’s “Knowing How” and Plato’s “Knowing That” The goal of Aristotle is knowledge in action and real knowing, which merge in the higher stratum of existence – the active mind.

- Happiness in “Nicomachean Ethics” by Aristotle The philosopher compares the life of gratification to that of slaves; the people who prefer this type of happiness are “vulgar,” live the same life as “grazing animals,” and only think about pleasure.

- Outlining Aristotle’s Ethics and Metaphysics As for one to be accorded the status of a professional he has to practice the skills required in that profession.

- Drama Elements Developed by Aristotle The sixth is a spectacle which is the visuals in the drama that include props, set, and actor’s costumes. An example of a tragic hero is King Macbeth in Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Macbeth.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Theories of Human Nature Chapter five of Kupperman’s book “Theories of human nature” looks at great philosophers, namely Plato’s and Aristotle’s points of view in trying to define humanity. The writer tries to illustrate the complexity of defining a […]

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Philosophical Differences According to Plato, the functioning of every human being is closely linked to the entire society. Therefore, the major difference here is that for Plato, the function of every individual is to improve the entire […]

- Aristotle Philosophical Perspective To understand the connection established by Aristotle between a good life and a rational one, it is first necessary to discuss the concept of good used in the Nicomachean Ethics.

- Philosophy: Free Will of Aristotle and Lucretius The philosopher says that every action having place under the influence of the external force is not a free will, which comes from the inner desire and motivation of an individual. Moreover, the movie is […]

- Art and Media Censorship: Plato, Aristotle, and David Hume The philosopher defines God and the creator’s responsibilities in the text of the Republic: The creator is real and the opposite of evil.

- Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics in Historical View Nicomachean Ethics is one of the most significant works of the prominent ancient philosopher, dedicated to the analysis of the moral purposes and virtues of a man.

- Book V in Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics The central discussion of the document revolves around justice to provide a scrutinized analysis of money and exchange. This is because the fair exchange of things is the reciprocity of proportion and not equality.

- If Aristotle Ran General Motors: Moral Perspective In the current paper, the author will extrapolate on what Morris is saying and analyze the impacts of the arguments on the workplace.

- Isocrates and Aristotle Views on Rhetorical Devices I find it hard to believe that such an accomplished rhetor as yourself, would doubt that the main rules and principles of rhetorical persuasion are universally applicable, and that it is specified by the mean […]

- Aristotle’s Ethics Conception and Workplace Relations Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is one of the ethical writings that have spurred understanding of ethics of work place relations. A critical discussion in the Nicomachean Ethics provided by Aristotle is the argument and conversation over […]

- Aristotle on Civic Relationships It takes account of the happiness is an end and not a means. It is a way of thinking with the set intention in mind; deliberation determines the end and not the means.

- Aristotle’s Notion of Civic Relationships According to Aristotle, it is impossible to provide a complete account of conditions that lead to the attainment of the highest level of happiness or public good.

- Aristotle’s and Modern Views on the Masses of Citizens It is also important to add that these values are only declared in many countries while the power is still in hands of the rich.

- Aristotle and Plato: How Do They Differ? Generally, Aristotle’s philosophy differs with that of Plato because the latter’s is too shallow to establish definitions or sensibly create standards.

- Aristotle’s Ideas on Civic Relationships Keeping law and order is thus essential in addition to evading things that are considered to be against the prospects of the society so as to be just, a virtue encouraged by Aristotle.

- What is Aristotle’s View on Trade? Aristotle argues that the art of exchanging goods or services in the pretext of trade is not good. Aristotle asserts that household management is necessary and honorable and therefore, families should never engage in retail […]

- Aristotle’s Definition of Virtue In particular, he writes that virtue is “a state that decides, consisting in a mean, relative to us, which is defined by reference to a reason, that is to say, to the reason by reference […]

- Aristotle With a Bust of Homer Rembrandt A careful study of the hair, the beards and the dress of Homer reveals that this is a painting of that era.

- Can Aristotle’s Theory of Happiness Be Achieved by Applying Friedman’s Ideas of Corporate Social Responsibilities? According to Aristotle, politics is the master of all arts since it is concerned with the end in itself. This is a central argument to the ideas of Aristotle and underscores his idea that politics […]

- Essence of Happiness of Indira’s Life According to Plato’s and Aristotle’s Views on Education She finds her inspiration in the languages and other subjects and, obviously, the girl knows that education is the best solution of solving a number of problems and difficulties that she may face during the […]

- Aristotle on Human Nature, State, and Slavery This should be done with restraint and caution in order not to compromise the validity of modern studies and to avoid bias, as evident in the studies of some historical philosophers in their quoting of […]

- Aristotle’s Ethics and Metaphysics He overlooks other important factors such as the act of feeling them in the most appropriate time, with special reference to the right objects, to the right individuals, with the right intention, and in the […]

- Ancient Political Theory: Plato and Aristotle Aristotle’s criticism of Plato’s the Republic in Politics II focused on political regimes and cities by stating in general that it would be a dangerous activity to leave the governance of a city to a […]

- Aristotle vs. Scientific Cannons They had a hypothesis, given their argument, that the heavier the object, the faster it would move towards the center of the universe. That is, there was a degree of regularity given a similarity in […]

- Aristotle’s Ideas on Civic Relationships: Happiness, the Virtues, Deliberation, Justice, and Friendship On building trust at work, employers are required to give minimum supervision to the employees in an effort to make the latter feel a sense of belonging and responsibility.

- Aristotle’s Fundamentals of Public Relationship The paper reviews the traits of the best working places and compares the ideas with those offered by Aristotle. In fact, through training, the employees are able to develop virtues that enhance interactions, and the […]

- How Aristotle Views Happiness Aristotle notes that “the attainment of the good for one man alone is, to be sure, a source of satisfaction; yet to secure it for a nation and for states is nobler and more divine”.

- Aristotle and Modern Work Relationships This is not the case in the contemporary work place where a myriad of factors contribute to the happiness of the employees.

- Sophocle and Aristotle For an individual to achieve the qualities of a tragic hero, his or her actions must be consistent. The qualities of a tragic hero are similar to the qualities exhibited by Oedipus.

- Aristotle and Relationship at Work: Outline The first level appeals to a part of the human soul that focuses on reason while the second part appeals to the part of the human soul that follows reason.

- Aristotle’s Ethical Theory The weakness of philosophical theories is that they are mere intellectual theories void actions or activities, which require habitual practice as a process of achieving moral virtues.

- Aristotle’s Philosophical Theories Aristotle argued that the understanding of nature could only be accomplished through the analysis of the aspects of nature as the first step in understanding the target object, and then processing the mental reaction of […]

- How Do Aristotle’s Ideas Show Him to Be an Ancient Philosopher?

- What Does Aristotle Identify as the Ultimate Human Good?

- How Closely Does Hamlet Match Aristotle’s Definition of a Tragic Hero?

- What Was Aristotle’s Thought on Friendship?

- How Did Aristotle Understand Bravery?

- What Would Aristotle Have Thought About a State Lottery?

- How Does Aristotle Address the Issue of Individual Rights?

- What Did Aristotle Mean by the Final Cause?

- How Are Ethics and Politics Related to Aristotle’s Philosophy?

- Did Aristotle Value Politics Less Than Materialism and Feelings?

- How Does Aristotle Define Happiness?

- Does Aristotle’s Function Argument Offer a Convincing Account of the Human Good?

- How Does Aristotle’s Ideas on Justice Influence the American Judicial System?

- Does Sophocles’ Antigone Fit Aristotle’s Definition of a Tragic Heroine?

- How Does Aristotle’s View of Politics Differ From That of Plato’s?

- Why Does Aristotle Believe That Morality Leads to Happiness?

- How Would Aristotle Respond to Utilitarianism?

- How Do Aristotle and Machiavelli Use the Middle Class and the Masses to Achieve Stable Political Organizations?

- Was Aristotle the First Physicist?

- How Does Aristotle Define the Good Life?

- What Did Aristotle Contribute to the Discipline of Logic?

- How Does Aristotle Oppose Platos Attack on Poetry?

- What Does Aristotle Define as Virtue?

- How Does Aristotle Understand the Human Being Through Virtue Ethics?

- What Were Aristotle’s Main Ideas?

- How Does Aristotle’s Anthropic Hylomorphism Relate to His Logical Hylomorphism?

- What Would Aristotle Think of Hannibal Lecter?

- How Does Aristotle Systematically Arrive at Eudemonia via a Concept of Function?

- Nietzsche Essay Titles

- Immanuel Kant Research Ideas

- Socrates Questions

- Karl Marx Questions

- John Stuart Mill Research Ideas

- Confucius Topics

- Max Weber Questions

- Homer Titles

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 22). 145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/aristotle-essay-topics/

"145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 22 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/aristotle-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 22 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/aristotle-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/aristotle-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "145 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/aristotle-essay-topics/.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

110 Aristotle Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

When it comes to ancient philosophy, one name that stands out is Aristotle. Known as one of the greatest thinkers in history, Aristotle's ideas have influenced countless fields of study, from politics and ethics to physics and biology. If you're tasked with writing an essay on Aristotle, you might be wondering where to start. To help you out, here are 110 Aristotle essay topic ideas and examples that cover a wide range of his works and theories:

- The concept of virtue in Aristotle's ethics.

- Aristotle's theory of the mean and its relevance in modern society.

- The relationship between happiness and virtue according to Aristotle.

- Aristotle's views on the purpose and function of government.

- A comparative analysis of Aristotle's and Plato's political philosophies.

- The role of education in Aristotle's theory of the ideal state.

- Aristotle's theory of causality and its application in scientific methodology.

- The concept of teleology in Aristotle's philosophy.

- Aristotle's theory of substance and its implications for metaphysics.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of potentiality and actuality in understanding change.

- Aristotle's views on the nature of the soul and its immortality.

- The role of pleasure in Aristotle's ethics.

- The concept of eudaimonia in Aristotle's ethical theory.

- Aristotle's theory of friendship and its importance in human relationships.

- The relationship between reason and virtue in Aristotle's ethics.

- Aristotle's views on the nature of art and its role in society.

- The concept of tragedy in Aristotle's Poetics.

- Aristotle's theory of rhetoric and its applications in persuasive communication.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of catharsis in understanding the emotional impact of art.

- Aristotle's views on the nature of truth and knowledge.

- The concept of syllogism in Aristotle's logic.

- Aristotle's theory of four causes and its relationship to explanation.

- The role of habit in Aristotle's ethics.

- Aristotle's theory of justice and its implications for legal systems.

- The concept of natural slavery in Aristotle's political philosophy.

- Aristotle's views on the nature of women and their role in society.

- A comparative analysis of Aristotle's and Nietzsche's theories of ethics.

- The relationship between virtue and pleasure in Aristotle's ethical theory.

- Aristotle's theory of the golden mean and its application in moral decision-making.

- The role of emotions in Aristotle's ethics.

- The concept of tragedy in Aristotle's theory of literature.

- Aristotle's views on the balance between individual freedom and social order.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of the unmoved mover in understanding the existence of God.

- The role of reason in Aristotle's theory of knowledge.

- Aristotle's theory of the self and its implications for personal identity.

- The concept of unity in Aristotle's metaphysics.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between body and soul.

- A comparative analysis of Aristotle's and Descartes' theories of the mind-body problem.

- Aristotle's theory of education and its role in shaping character.

- The concept of tragedy in Aristotle's theory of drama.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between nature and nurture.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of the polis in understanding the origins of political society.

- The role of women in Aristotle's ideal state.

- Aristotle's theory of the good life and its implications for personal fulfillment.

- The concept of justice in Aristotle's ethical theory.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between ethics and politics.

- A comparative analysis of Aristotle's and Kant's theories of ethics.

- The role of reason in Aristotle's theory of moral virtue.

- Aristotle's theory of the soul and its implications for the afterlife.

- The concept of chance in Aristotle's theory of causality.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between art and morality.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of tragedy in understanding human emotions.

- Aristotle's theory of rhetoric and its applications in public speaking.

- The role of pleasure in Aristotle's theory of aesthetics.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between language and thought.

- A comparative analysis of Aristotle's and Hume's theories of ethics.

- The concept of happiness in Aristotle's ethical theory.

- Aristotle's theory of the divine and its implications for religious belief.

- The role of virtue in Aristotle's theory of political leadership.

- Aristotle's views on the concept of beauty and its role in art.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of the soul in understanding human consciousness.

- Aristotle's theory of causality and its application in understanding natural phenomena.

- The concept of self-realization in Aristotle's ethical theory.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between reason and emotion.

- A comparative analysis of Aristotle's and Mill's theories of ethics.

- The role of wisdom in Aristotle's theory of moral virtue.

- Aristotle's theory of the good and its implications for personal values.

- The concept of friendship in Aristotle's ethical theory.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between ethics and religion.

- The significance of Aristotle's theory of tragedy in understanding human suffering.

- Aristotle's theory of rhetoric and its applications in political discourse.

- Aristotle's views on the relationship between language and reality.

- The concept of virtue in Aristotle's ethical theory.

These essay topic ideas provide a comprehensive range of areas in which you can explore Aristotle's philosophy. From ethics and politics to metaphysics and aesthetics, Aristotle's theories continue to be relevant and influential today. Choose a topic that interests you the most and delve into the fascinating world of Aristotle's ideas. Good luck with your essay!

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

125 Aristotle Essay Topics

🏆 best essay topics on aristotle, ✍️ aristotle essay topics for college, 👍 good aristotle research topics & essay examples, 🎓 most interesting aristotle research titles, 💡 simple aristotle essay ideas.

- Aristotle and Virtue Ethics

- Plato and Aristotle Views on the Concept of Knowledge

- Plato and Aristotle Differences

- The Difference Between Socrates’s and Aristotle’s Prescriptions of Way of Life

- The Difference Between Plato and Aristotle’s Views

- Aristotle Theory About Euthanasia – Ethics

- Philosophy: Aristotle’s View on Substance

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Approaches to Metaphysics Comparison Plato’s and Aristotle’s approaches are thought to be polar: the idealistic and the materialistic, but they intersect in the comprehension and importance of the non-material.

- Aristotle, Mills, and Kant on Ethical Dilemmas Aristotle, Mill, and Kant provide their approaches to solving ethical dilemmas. The paper compares the three theories.

- Theories of Governance: Plato’s and Aristotle’s Theories This paper explores Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories of governance and their relevance to governance thought throughout history, as well as current gun issues.

- Aristotle’s View on the Relationship Between Soul and Body Aristotle’s work called “De Anima” represents a study of the question of the soul and is phenomenal for the time of the thinker.

- Plato and Aristotle’s Philosophy on Common Interest While Aristotle strongly rejects Plato’s claim that there is no value in collective unity, this essay illustrates that both philosophers have a common view.

- Aristotle’s Teleological Understanding of Ethics as Virtue in Modern Society The described reasoning concerning Aristotle’s teleological understanding of ethics can be seen as a sensible platform for decision-making in the modern context.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Dualism and Theory of Forms The difference between the ways in which Plato and Aristotle approached the theory of forms offers background into how the philosophers chose their stances on different phenomena.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Argument on Forms and Universals The article is a comparison of the theories of Plato and Aristotle concerning the explanation of the nature of forms and universal states.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Ideas of Ethics Plato and Aristotle were both two individuals who defiantly had brilliant ideas on how to make the world a good place to live.

- Aristotle’s Conception of Science Aristotle’s conception of science has remained a fundamental principle for guiding modern scholars to pursue new truths.

- Comparing Philosophy of Plato and Aristotle Aristotle is a disciple of Plato. Aristotle believed that Plato’s theory of ideas was entirely insufficient to explain empirical reality

- Plato’s Political Philosophy and Aristotle’s Political Science This essay will examine the reasons behind different perceptions of Plato’s and Aristotle’s works and their perspectives on government and politics.

- Odysseus Personality in Terms of Aristotle’s Ethics The purpose of the essay is to prove that Odysseus had crucial positive human characteristics described by Aristotle, and also, in the framework of practical philosophy.

- Cicero’s and Aristotle’s Friendship Notions In contrast to Aristotle, Cicero believes that there are some qualities that make a good friend and a bad friend.

- Citizenship and Civil Disobedience According to Aristotle and Sophocles Summarizing Aristotle’s ideas on this issue and applying them to a well-known play, “Antigone” by Sophocles, helps bring these concepts of Citizenship into clearer focus.

- Aristotle’s Biography: Philosopher’s Teaching and Outlook The path Aristotle followed as a philosopher was by large predetermined by his family background and circumstances of early years.

- Confucius, Aristotle, and Plato: The Issue of Harmony Confucius states that harmony is an equilibrium. Aristotle describes harmony as a connection between different and even opposite people. For Plato, harmony is within a soul.

- Ideas of Plato and Aristotle as a Basis for Medieval and Early Modern Period Concept of Soul Depending on the solution to this problem, the emphasis is shifted either to the biological nature of a person or to their spiritual essence.

- Happiness in Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics” In the “Nicomachean Ethics,” Aristotle argues that there are different lives people tend to consider happiness; they include the life of political action, money-making, etc.

- Socrates in Aristotle’s and Plato’s Works This paper discusses the depiction of Socrates in Aristophanes Clouds, Plato’s dialogues, and how Aristophanes Cloud’s depiction differs from Plato’s dialogues.

- Aristotle’s Views on the Concept of Friendship Friendship, in Aristotle’s understanding, refers to any kind of interpersonal relationship that is both affectionate and beneficial.

- Aristotle’s Concept of Virtue Ethics Aristotle attached particular importance to the moral ethics of the individual’s personality traits, rather than social duties and rules.

- Aristotle’s Ethical Theory and Its Influences The essay describes the importance of Aristotle’s ethical theory to modern ethics and analyzes the key points of his most iconic writings.

- Aristotle and Augustine on Doing Wrong Aristotle, the Ancient Greek philosopher who lived in the 4th century BC and was a student of Plato, had a huge intellectual range and was involved in many different branches of science.

- Aristotle’s Involvement in Social Issues Aristotle’s philosophy united several approaches and regarded a human being as a multidimensional creature, which accounts for his entirely new look at society.

- Comparison Between Plato and Aristotle’s View on Women Plato and Aristotle have separate views on women where one of them advocated for equality, and the other proposed that there should be ab alienation of women.

- Aristotle’s Perspective on the Greek Tragedy Due to Aristotle’s concept of tragedy, modern audiences can examine a play and form a deep relationship with the protagonist.

- How Kreon Is the Tragic Hero, Based on Aristotle’s Principles Kreon is the tragic hero based on Aristotle’s principles because he meets all the four characteristics that go with that title.

- Appropriation of Aristotle’s Ideas in Christian Philosophy It should be mentioned that the Christian faith first spread among the Greek elites who were educated in the thought of Aristotle, Plato, or Socrates.

- Aristotle and Plato Works Comparison Along with Socrates and Plato, Aristotle is believed to be one of the most ancient Greek philosophers. Being arguably the most educated man of those times, Aristotle had a wide range of interests.

- Plato’s and Aristotle’s Views on Philosophy It is worth noting that the two great philosophers Plato and Aristotle had polar views on the essence, and the philosophy in general.

- Aristotle’s and Machiavelli’s Views on the Virtue This paper aims at discussing the essence of virtue, its goals, and contradictions in terms of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Machiavelli’s Prince.

- Aristotle’s Views on Ethics Ethics for people’s lives viewed in Aristotle’s argument stating that all humans share a certain function in life. This paper will present an objection to Aristotle’s function argument.

- Seneca’s Views on Anger Arguments of Aristotle Everyone gets annoyed at one time or the other. However, there are some people who are always angry. Both Aristotle and Seneca show that fury leads to varying reactions among different people.

- “The Nicomachean Ethics” Book by Aristotle The work “The Nicomachean Ethics” by Aristotle is a major guiding force in academic and political ethics, which is a fundamental factor for human existence.

- St. Thomas’s Natural Law Teaching and Aristotle’s Teaching in Ethics Jean-Jacques Rousseau criticized all prior natural law theories by stating that it was impossible to understand the laws of nature without understanding real nature.

- Plato’s, Aristotle’s, and Machiavelli’s Perspectives on the Ideal Form of Government Since Plato, Aristotle, and Machiavelli each single out a particular characteristic of human nature, their idea of a perfect political regime is tethered to it.

- Plato’s vs. Aristotle’s Political Approaches Aristotle’s political approach is different from Plato’s approach in the sense that Plato’s approach is not applicable in the ideal society.

- The Happiness Concept in Aristotle’s Ethics The concept of Happiness presented by the Greek philosopher Aristotle lies beyond the traditional notion of Happiness that has developed in the collective consciousness.

- Discussion of Aristotle Rhetoric The reading discusses the idea of rhetoric as a means of persuasion because Aristotle argues effective persuasion depends on the successful use of ethos, logos, and pathos.

- Han Fei and Aristotle: Interpret of the Passage by Confucius The primary aim of the current work is to interpret the passage by Confucius and analyze it from the philosophical perspectives of Han Fei and Aristotle.

- Plato’s, Aristotle’s, and Socrates’ Philosophical Ideas Despite the lack of similarity, the teachings of different philosophies are identified more easily, and their nature, as well as the similar concepts that appear in philosophy.

- Explaining Aristotle’s Understanding of Virtue For Aristotle and his followers, virtue is not a simple term connected to positive levels of morality in a human being.

- Virtue: Views of Aristotle and Machiavelli The paper discusses Aristotle and Machiavelli had divergent perspectives on the concept of virtue, as it is a balanced approach to life in both civic and moral aspects.

- Aristotle and His Vision of the Virtues of Man This work provides a brief description of Aristotle’s ideas about the virtues of character, virtues, and moral behavior of a person.

- Analysis of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics In this article, Aristotle’s concept of Nicomachean ethics is based on the philosophical view that happiness is the only justifiable ultimate end that people pursue.

- Connections Between Aristotle’s Views of the Universe and Aquinas’s Aristotle inspired many philosophers and thinkers with his ideas of how the universe functions. One of the people who built on the ideas of Aristotle was Aquinas.

- Video Advertisement: The Efficiency of the Aristotle’s Rhetoric This essay examines the effectiveness of using Ethos, Pathos, and Logos as the persuasive tools in the “Jason Momoa Super Bowl Commercial 2020. Rocket Mortgage” advertisement.

- Aristotle’s Ideas of Persuasion in Advertising The analysis of modern advertising campaigns from the point of view that decision-making is not based on logical thinking, but on emotional motivation, as Aristotle proved.

- Plato, Aristotle and Preferable Response to Literature The main task of the present paper is to analyze Aristotle and Plato’s points of view concerning art and to choose the one that is the most appropriate to reading literature.

- Aristotle’s Discussion in Nichomanchean Ethics Aristotle’s discussion in Nichomanchean Ethics provides a perfect definition of an ethical society and the meaning of such ethics.

- Kant’s and Aristotle’s Ethical Philosophy Kant claims that a person who helps others, with pleasure, from motives of natural sympathy displays no moral worth. It is helpful to take a look at Aristotle.

- Ethics and Morality as Philosophical Concepts: Definitions According to Aristotle, Dante, and Kant The work is aimed to tell about enlightenment according to Kant, Aristotle’s theory of ethics, moral philosophy and the arrangement of Dante’s hell and definition of justice.

- Philosophy. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics This paper will discuss and analyze the importance of friendship, virtue, and endurance and the way Aristotle presents these concepts.

- Virtue Perception by Aristotle and Today’s Society By analyzing Aristotle’s view of virtue, as well as its relevance in today’s society, one may comprehend its critical aspects and crucial impact on humanity.

- Aristotle and Aquinas on Happiness In his most renowned work, Nicomachean Ethics, the philosopher Aristotle explored the idea of a supreme good of people.

- Morality in Kant’s, Mill’s, Aristotle’s Philosophies This paper compares the positions of Kant, Mill, and Aristotle on the nature of morality and its relationship with reason or intellect, and with feelings.

- Equality in “The Politics” by Aristotle One of the outstanding works that discuss the origins of political life and organization of society is “The Politics” by Aristotle.

- Aristotle and His Views on Political Success

- Aristotle and the Irony of Guilt

- Aristotle and Plato’s View of Slavery

- Antigone and Creon Appreciated From Aristotle’s Theory of Poetics

- Aristotle and Adam Smith on Reason and Sentiment

- Nature and Biology According to Aristotle

- Aristotle and Human Origins

- Aristotle’s Rhetoric and the Ethics of Modern Advertising

- Aristotle and Plato’s Views on Knowledge

- Aristotle & Alchohol Abuse

- Aristotle’s Most Ideal Social and Political Good

- Aristotle and Charles Darwin: Two of the Great Biologist of All Time

- Human Reproduction and the Views of Aristotle

- Aristotle and Plato’s Views on Reality

- Plato and Aristotle’s Impact on Rhetoric

- Aristotle and the Development of Value Theory

- Aristotle and Citizenship Intellectual Virtue

- Friendship and Marriage According to Barbara Whitehead and Aristotle

- Happiness and the Good in Humanity in Nichomachean Ethics, a Book by Aristotle

- Aristotle’s Distinction Between Tragedy and Epic Poetry

- Goodness, Happiness, and Virtues in Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle

- Aristotle and Buddhism: Comparing Philosophies

- Aristotle and the Canadian Political System

- Ethics and Religion According to Augustine and Aristotle

- Aristotle’s Definition and Description of Human Function

- Ethics and Psychology Theories of Aristotle

- Aristotle and His View of Women

- Plato and Aristotle’s Life-Blood Philosophy of Dialect Discussion

- Aristotle and the Philosophy of Happiness

- Oedipus and Othello Exemplify Aristotle’s Definition of a Tragic Hero

- Aristotle’s Life and Contributions to Western Civilization

- Aristotle: Substance, Demonstrative Knowledge, Luck, and Chance

- Alfarabi and Aristotle: The Four Causes and the Four Stages of the Doctrine of the Intelligence

- Philosophy: Aristotle and Medical Knowledge

- Aristotle’s Ethical Theory and How It Conflicts

- John Stuart Mill and Aristotle‘s Opposing Argumentative Theories

- Man’s Final Good and Methods of Determination in Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle

- Aristotle and the Four Causes of the End Purpose of an Object or Action

- Aristotle’s Three Motivations for Friendship

- Aristotle and Juvenile Delinquency

- Comparing and Contrasting the Philosophers Aristotle and Plato

- Aristotle and His Basic Philosophies

- Ethics and Morals According to Kant and Aristotle

- Aristotle and the Correspondence Theory of Truth

- Aquinas vs. Aristotle: Justice as Virtue

- Aristotle and the Appeal to Reason

- Aristotle and His Idea of the Ideal Constitution

- Aristotle and Open Population Thinking

- Human Nature and the Views of Augustine and Aristotle

- Ethics and Morality According to Aristotle in the Legal Defense of a Guilty Man

- Aristotle and His Followers of the Aristotelian Tradition

- Similarities Between Aristotle and Aquinas

- Aristotle and Freud and the Theory of Tragedy

- Happiness and Morality According to Aristotle

- Aristotle’s Poetics: Catharsis and Rasas

- Aristotle and Epicurus Debate on Pleasure and Politics

- Plato, Aristotle, and Machiavelli on Democratic Rule

- Ancient Political Thought: Aristotle and Plato

- Aristotle and His Ethical Beliefs

- Abortion and the Philosophies of David Hume and Aristotle

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, March 1). 125 Aristotle Essay Topics. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/aristotle-essay-topics/

"125 Aristotle Essay Topics." StudyCorgi , 1 Mar. 2022, studycorgi.com/ideas/aristotle-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) '125 Aristotle Essay Topics'. 1 March.

1. StudyCorgi . "125 Aristotle Essay Topics." March 1, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/aristotle-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "125 Aristotle Essay Topics." March 1, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/aristotle-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "125 Aristotle Essay Topics." March 1, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/aristotle-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Aristotle were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 20, 2024 .

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

The Academy

- Extant works

- Syllogistic

- Propositions and categories

- The continuum

- The unmoved mover

- Philosophy of science

- Philosophy of mind

- Action and contemplation

- Political theory

- Rhetoric and poetics

What did Aristotle do?

Where did aristotle live, who were aristotle’s teachers and students, how many works did aristotle write, how did aristotle influence subsequent philosophy and science.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Embryo Project Encyclopedia - Aristotle (384-322 BCE)

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Aristotle (384–322 bc): philosopher and scientist of ancient Greece

- University of Washington - Introduction to Aristotle

- Great Thinkers - Aristotle

- Humanities LibreTexts - Biography of Aristotle

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Aristotle

- University of California Museum of Paleontology - Biography of Aristotle

- World History Encyclopedia - Aristotle

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Aristotle

- The Ethics Centre - Aristotle, the Ancient Greek Philosopher

- Aristotle - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Aristotle - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Aristotle was one of the greatest philosophers who ever lived and the first genuine scientist in history. He made pioneering contributions to all fields of philosophy and science, he invented the field of formal logic , and he identified the various scientific disciplines and explored their relationships to each other. Aristotle was also a teacher and founded his own school in Athens, known as the Lyceum .

After his father died about 367 BCE, Aristotle journeyed to Athens, where he joined the Academy of Plato. He left the Academy upon Plato’s death about 348, traveling to the northwestern coast of present-day Turkey . He lived there and on the island of Lésbos until 343 or 342, when King Philip II of Macedonia summoned him to the Macedonian capital, Pella , to act as tutor to Philip’s young teenage son, Alexander, which he did for two or three years. Aristotle presumably lived somewhere in Macedonia until his (second) arrival in Athens in 335. In 323 hostility toward Macedonians in Athens prompted Aristotle to flee to the island of Euboea, where he died the following year.

Aristotle’s most famous teacher was Plato (c. 428–c. 348 BCE), who himself had been a student of Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE). Socrates, Plato , and Aristotle, whose lifetimes spanned a period of only about 150 years, remain among the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy. Aristotle’s most famous student was Philip II’s son Alexander, later to be known as Alexander the Great , a military genius who eventually conquered the entire Greek world as well as North Africa and the Middle East . Aristotle’s most important philosophical student was probably Theophrastus , who became head of the Lyceum about 323.

Aristotle wrote as many as 200 treatises and other works covering all areas of philosophy and science . Of those, none survives in finished form. The approximately 30 works through which his thought was conveyed to later centuries consist of lecture notes (by Aristotle or his students) and draft manuscripts edited by ancient scholars, notably Andronicus of Rhodes , the last head of the Lyceum , who arranged, edited, and published Aristotle’s extant works in Rome about 60 BCE. The naturally abbreviated style of these writings makes them difficult to read, even for philosophers.

Aristotle’s thought was original, profound, wide-ranging, and systematic. It eventually became the intellectual framework of Western Scholasticism , the system of philosophical assumptions and problems characteristic of philosophy in western Europe during the Middle Ages . In the 13th century St. Thomas Aquinas undertook to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy and science with Christian dogma, and through him the theology and intellectual worldview of the Roman Catholic Church became Aristotelian. Since the mid-20th century, Aristotle’s ethics has inspired the field of virtue theory, an approach to ethics that emphasizes human well-being and the development of character. Aristotle’s thought also constitutes an important current in other fields of contemporary philosophy, especially metaphysics, political philosophy, and the philosophy of science.

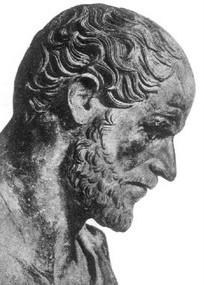

Aristotle (born 384 bce , Stagira, Chalcidice , Greece—died 322, Chalcis , Euboea) was an ancient Greek philosopher and scientist, one of the greatest intellectual figures of Classical antiquity and Western history. He was the author of a philosophical and scientific system that became the framework and vehicle for both Christian Scholasticism and medieval Islamic philosophy . Even after the intellectual revolutions of the Renaissance , the Reformation , and the Enlightenment , Aristotelian concepts remained embedded in Western thinking .

Aristotle’s intellectual range was vast, covering most of the sciences and many of the arts, including biology , botany , chemistry , ethics , history , logic , metaphysics , rhetoric , philosophy of mind , philosophy of science , physics , poetics, political theory, psychology , and zoology . He was the founder of formal logic , devising for it a finished system that for centuries was regarded as the sum of the discipline; and he pioneered the study of zoology, both observational and theoretical, in which some of his work remained unsurpassed until the 19th century. But he is, of course, most outstanding as a philosopher. His writings in ethics and political theory as well as in metaphysics and the philosophy of science continue to be studied, and his work remains a powerful current in contemporary philosophical debate.

This article deals with Aristotle’s life and thought. For the later development of Aristotelian philosophy , see Aristotelianism . For treatment of Aristotelianism in the full context of Western philosophy, see philosophy, Western .

Aristotle was born on the Chalcidic peninsula of Macedonia, in northern Greece . His father, Nicomachus, was the physician of Amyntas III (reigned c. 393–c. 370 bce ), king of Macedonia and grandfather of Alexander the Great (reigned 336–323 bce ). After his father’s death in 367, Aristotle migrated to Athens , where he joined the Academy of Plato (c. 428–c. 348 bce ). He remained there for 20 years as Plato’s pupil and colleague.

Many of Plato’s later dialogues date from these decades, and they may reflect Aristotle’s contributions to philosophical debate at the Academy. Some of Aristotle’s writings also belong to this period, though mostly they survive only in fragments. Like his master, Aristotle wrote initially in dialogue form, and his early ideas show a strong Platonic influence. His dialogue Eudemus , for example, reflects the Platonic view of the soul as imprisoned in the body and as capable of a happier life only when the body has been left behind. According to Aristotle, the dead are more blessed and happier than the living, and to die is to return to one’s real home.

Another youthful work, the Protrepticus (“Exhortation”), has been reconstructed by modern scholars from quotations in various works from late antiquity. Everyone must do philosophy, Aristotle claims, because even arguing against the practice of philosophy is itself a form of philosophizing. The best form of philosophy is the contemplation of the universe of nature; it is for this purpose that God made human beings and gave them a godlike intellect. All else—strength, beauty, power, and honour—is worthless.

It is possible that two of Aristotle’s surviving works on logic and disputation, the Topics and the Sophistical Refutations , belong to this early period. The former demonstrates how to construct arguments for a position one has already decided to adopt; the latter shows how to detect weaknesses in the arguments of others. Although neither work amounts to a systematic treatise on formal logic, Aristotle can justly say, at the end of the Sophistical Refutations , that he has invented the discipline of logic—nothing at all existed when he started.

During Aristotle’s residence at the Academy, King Philip II of Macedonia (reigned 359–336 bce ) waged war on a number of Greek city-state s. The Athenians defended their independence only half-heartedly, and, after a series of humiliating concessions , they allowed Philip to become, by 338, master of the Greek world. It cannot have been an easy time to be a Macedonian resident in Athens.

Within the Academy, however, relations seem to have remained cordial. Aristotle always acknowledged a great debt to Plato; he took a large part of his philosophical agenda from Plato, and his teaching is more often a modification than a repudiation of Plato’s doctrines. Already, however, Aristotle was beginning to distance himself from Plato’s theory of Forms, or Ideas ( eidos ; see form ). (The word Form , when used to refer to Forms as Plato conceived them, is often capitalized in the scholarly literature; when used to refer to forms as Aristotle conceived them, it is conventionally lowercased.) Plato had held that, in addition to particular things, there exists a suprasensible realm of Forms, which are immutable and everlasting. This realm, he maintained, makes particular things intelligible by accounting for their common natures: a thing is a horse, for example, by virtue of the fact that it shares in, or imitates, the Form of “Horse.” In a lost work, On Ideas , Aristotle maintains that the arguments of Plato’s central dialogues establish only that there are, in addition to particulars, certain common objects of the sciences. In his surviving works as well, Aristotle often takes issue with the theory of Forms, sometimes politely and sometimes contemptuously. In his Metaphysics he argues that the theory fails to solve the problems it was meant to address. It does not confer intelligibility on particulars, because immutable and everlasting Forms cannot explain how particulars come into existence and undergo change. All the theory does, according to Aristotle, is introduce new entities equal in number to the entities to be explained—as if one could solve a problem by doubling it. ( See below Form .)

When Plato died about 348, his nephew Speusippus became head of the Academy, and Aristotle left Athens. He migrated to Assus , a city on the northwestern coast of Anatolia (in present-day Turkey), where Hermias , a graduate of the Academy, was ruler. Aristotle became a close friend of Hermias and eventually married his ward Pythias. Aristotle helped Hermias to negotiate an alliance with Macedonia, which angered the Persian king, who had Hermias treacherously arrested and put to death about 341. Aristotle saluted Hermias’s memory in “ Ode to Virtue,” his only surviving poem.

While in Assus and during the subsequent few years when he lived in the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos , Aristotle carried out extensive scientific research, particularly in zoology and marine biology . This work was summarized in a book later known, misleadingly, as The History of Animals , to which Aristotle added two short treatises , On the Parts of Animals and On the Generation of Animals . Although Aristotle did not claim to have founded the science of zoology, his detailed observations of a wide variety of organisms were quite without precedent. He—or one of his research assistants—must have been gifted with remarkably acute eyesight, since some of the features of insects that he accurately reports were not again observed until the invention of the microscope in the 17th century.

The scope of Aristotle’s scientific research is astonishing. Much of it is concerned with the classification of animals into genus and species; more than 500 species figure in his treatises, many of them described in detail. The myriad items of information about the anatomy, diet, habitat, modes of copulation, and reproductive systems of mammals, reptiles, fish, and insects are a melange of minute investigation and vestiges of superstition. In some cases his unlikely stories about rare species of fish were proved accurate many centuries later. In other places he states clearly and fairly a biological problem that took millennia to solve, such as the nature of embryonic development.

Despite an admixture of the fabulous, Aristotle’s biological works must be regarded as a stupendous achievement. His inquiries were conducted in a genuinely scientific spirit, and he was always ready to confess ignorance where evidence was insufficient. Whenever there is a conflict between theory and observation, one must trust observation, he insisted, and theories are to be trusted only if their results conform with the observed phenomena.

In 343 or 342 Aristotle was summoned by Philip II to the Macedonian capital at Pella to act as tutor to Philip’s 13-year-old son, the future Alexander the Great. Little is known of the content of Aristotle’s instruction; although the Rhetoric to Alexander was included in the Aristotelian corpus for centuries, it is now commonly regarded as a forgery. By 326 Alexander had made himself master of an empire that stretched from the Danube to the Indus and included Libya and Egypt. Ancient sources report that during his campaigns Alexander arranged for biological specimens to be sent to his tutor from all parts of Greece and Asia Minor .

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Aristotle (384 b.c.e.—322 b.c.e.).

A prolific writer, lecturer, and polymath, Aristotle radically transformed most of the topics he investigated. In his lifetime, he wrote dialogues and as many as 200 treatises, of which only 31 survive. These works are in the form of lecture notes and draft manuscripts never intended for general readership. Nevertheless, they are the earliest complete philosophical treatises we still possess.

As the father of western logic, Aristotle was the first to develop a formal system for reasoning. He observed that the deductive validity of any argument can be determined by its structure rather than its content, for example, in the syllogism: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal. Even if the content of the argument were changed from being about Socrates to being about someone else, because of its structure, as long as the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Aristotelian logic dominated until the rise of modern propositional logic and predicate logic 2000 years later.

The emphasis on good reasoning serves as the backdrop for Aristotle’s other investigations. In his natural philosophy, Aristotle combines logic with observation to make general, causal claims. For example, in his biology, Aristotle uses the concept of species to make empirical claims about the functions and behavior of individual animals. However, as revealed in his psychological works, Aristotle is no reductive materialist. Instead, he thinks of the body as the matter, and the psyche as the form of each living animal.

Though his natural scientific work is firmly based on observation, Aristotle also recognizes the possibility of knowledge that is not empirical. In his metaphysics, he claims that there must be a separate and unchanging being that is the source of all other beings. In his ethics, he holds that it is only by becoming excellent that one could achieve eudaimonia, a sort of happiness or blessedness that constitutes the best kind of human life.

Aristotle was the founder of the Lyceum, a school based in Athens, Greece; and he was the first of the Peripatetics, his followers from the Lyceum. Aristotle’s works, exerted tremendous influence on ancient and medieval thought and continue to inspire philosophers to this day.

Table of Contents

- Life and Lost Works

- The Meaning and Purpose of Logic

- Demonstrative Syllogistic

- Induction, Experience, and Principles

- Rhetoric and Poetics

- Cosmology and Geology

- Mathematics

- First Philosophy

- Habituation and Excellence

- Ethical Deliberation

- Self and Others

- The Household and the State

- Aristotle’s Influence

- Abbreviations of Aristotle’s Works

- Other Abbreviations

- Aristotle’s Complete Works

- Life and Early Works

- Theoretical Philosophy

- Practical Philosophy

1. Life and Lost Works

Though our main ancient source on Aristotle’s life, Diogenes Laertius, is of questionable reliability, the outlines of his biography are credible. Diogenes reports that Aristotle’s Greek father, Nicomachus, served as private physician to the Macedonian king Amyntas (DL 5.1.1). At the age of seventeen, Aristotle migrated to Athens where he joined the Academy, studying under Plato for twenty years (DL 5.1.9). During this period Aristotle acquired his encyclopedic knowledge of the philosophical tradition, which he draws on extensively in his works.

Aristotle left Athens around the time Plato died, in 348 or 347 B.C.E. One explanation is that as a resident alien, Aristotle was excluded from leadership of the Academy in favor of Plato’s nephew, the Athenian citizen Speusippus. Another possibility is that Aristotle was forced to flee as Philip of Macedon’s expanding power led to the spread of anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens (Chroust 1967). Whatever the cause, Aristotle subsequently moved to Atarneus, which was ruled by another former student at the Academy, Hermias. During his three years there, Aristotle married Pythias, the niece or adopted daughter of Hermias, and perhaps engaged in negotiations or espionage on behalf of the Macedonians (Chroust 1972). Whatever the case, the couple relocated to Macedonia, where Aristotle was employed by Philip, serving as tutor to his son, Alexander the Great (DL 5.1.3–4). Aristotle’s philosophical career was thus directly entangled with the rise of a major power.

After some time in Macedonia, Aristotle returned to Athens, where he founded his own school in rented buildings in the Lyceum . It was presumably during this period that he authored most of his surviving texts, which have the appearance of lecture transcripts edited so they could be read aloud in Aristotle’s absence. Indeed, this must have been necessary, since after his school had been in operation for thirteen years, he again departed from Athens, possibly because a charge of impiety was brought against him (DL 5.1.5). He died at age 63 in Chalcis (DL 5.1.10).

Diogenes tells us that Aristotle was a thin man who dressed flashily, wearing a fashionable hairstyle and a number of rings. If the will quoted by Diogenes (5.1.11–16) is authentic, Aristotle must have possessed significant personal wealth, since it promises a furnished house in Stagira, three female slaves, and a talent of silver to his concubine, Herpyllis. Aristotle fathered a daughter with Pythias and, with Herpyllis, a son, Nicomachus (named after his grandfather), who may have edited Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics . Unfortunately, since there are few extant sources on Aristotle’s life, one’s judgment about the accuracy and completeness of these details depends largely on how much one trusts Diogenes’ testimony.

Since commentaries on Aristotle’s work have been produced for around two thousand years, it is not immediately obvious which sources are reliable guides to his thought. Aristotle’s works have a condensed style and make use of a peculiar vocabulary. Though he wrote an introduction to philosophy, a critique of Plato’s theory of forms, and several philosophical dialogues, these works survive only in fragments. The extant Corpus Aristotelicum consists of Aristotle’s recorded lectures, which cover almost all the major areas of philosophy. Before the invention of the printing press, handwritten copies of these works circulated in the Near East, northern Africa, and southern Europe for centuries. The surviving manuscripts were collected and edited in August Immanuel Bekker’s authoritative 1831–1836 Berlin edition of the Corpus (“Bekker” 1910). All references to Aristotle’s works in this article follow the standard Bekker numbering.

The extant fragments of Aristotle’s lost works, which modern commentators sometimes use as the basis for conjectures about his philosophical development, are noteworthy. A fragment of his Protrepticus preserves a striking analogy according to which the psyche or soul’s attachment to the body is a form of punishment:

The ancients blessedly say that the psyche pays penalty and that our life is for the atonement of great sins. And the yoking of the psyche to the body seems very much like this. For they say that, as Etruscans torture captives by chaining the dead face to face with the living, fitting each to each part, so the psyche seems to be stretched throughout, and constrained to all the sensitive members of the body. (Pistelli 1888, 47.24–48.1)

According to this allegedly inspired theory, the fetters that bind the psyche to the body are similar to those by which the Etruscans torture their prisoners. Just as the Etruscans chain prisoners face to face with a dead body so that each part of the living body touches a part of the corpse, the psyche is said to be aligned with the parts of one’s living body. On this view, the psyche is embodied as a painful but corrective atonement for its badness. (See Bos 2003 and Hutchinson and Johnson’s webpage ).

The incompatibility of this passage with Aristotle’s view that the psyche is inseparable from the body (discussed below) has been explained in various ways. Neo-Platonic commentators distinguish between Aristotle’s esoteric and exoteric writings, that is, writings intended for circulation within his school, and writings like the Protrepticus intended for a broader reading public (Gerson 2005, 47–75). Some modern scholars have argued to the contrary that the imprisonment of the psyche in the body indicates that Aristotle was still a Platonist at the time he composed the Protrepticus , which must have been written earlier than his mature works (Jaeger 1948, 100). Aristotle’s dialogue Eudemus , which contains arguments for the immortality of the psyche, and his Politicus , which is about the ideal statesman, seem to corroborate the view that Aristotle’s exoteric works hold much that is Platonic in spirit (Chroust 1965; 1966). The latter contains the seemingly Platonic assertion that “the good is the most exact of measures” (Kroll 1902, 168: 927b4–5).

But not all agree. Owen (1968, 162–163) argues that Aristotle’s fundamental logical distinction between individual and species depends on an antecedent break with Plato. According to this view, Aristotle’s On Ideas (Fine 1993), a collection of arguments against Platonic forms , shows that Aristotle rejected Platonism early in his career, though he later became more sympathetic to the master’s views. However, as Lachterman (1980) points out, such historical theses depend on substantive hermeneutical assumptions about how to read Aristotle and on theoretical assumptions about what constitutes a philosophical system. This article focuses not on this historical debate but on the theories propounded in Aristotle’s extant works.

2. Analytics or “Logic”

Aristotle is usually identified as the founder of logic in the West (although autonomous logical traditions also developed in India and China ), where his “Organon,” consisting of his works the Categories , On Interpretation , Prior Analytics , Posterior Analytics , Sophistical Refutations , and Topics , long served as the traditional manuals of logic. Two other works— Rhetoric and Poetics —are not about logic, but also concern how to communicate to an audience. Curiously, Aristotle never used the words “logic” or “organon” to refer to his own work but calls this discipline “analytics.” Though Aristotelian logic is sometimes referred to as an “art” (Ross 1940, iii), it is clearly not an art in Aristotle’s sense, which would require it to be productive of some end outside itself. Nevertheless, this article follows the convention of referring to the content of Aristotle’s analytics as “logic.”

a. The Meaning and Purpose of Logic