If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 6

- Life after slavery for African Americans

- The origins of Jim Crow - introduction

- Origins of Jim Crow - the Black Codes and Reconstruction

- Origins of Jim Crow - the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

- Origins of Jim Crow - Compromise of 1877 and Plessy v. Ferguson

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- The Compromise of 1877

The New South

- The South after the Civil War

- Proponents of the New South envisioned a post-Reconstruction southern economy modeled on the North’s embrace of the Industrial Revolution .

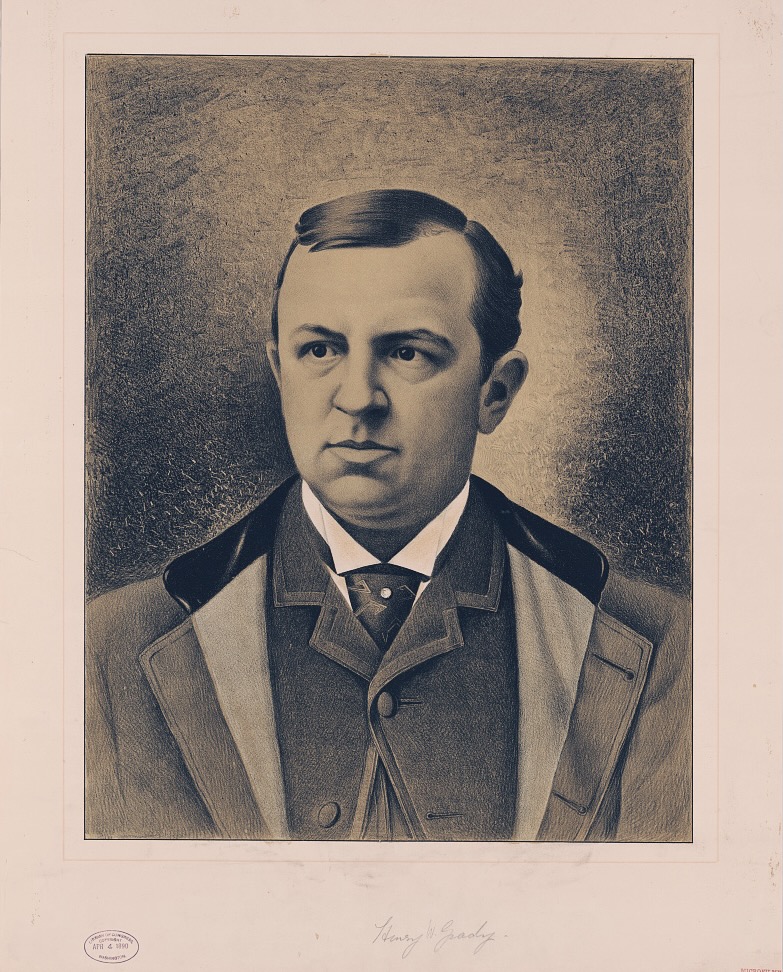

- Henry W. Grady , a newspaper editor in Atlanta, Georgia, coined the phrase the "New South” in 1874. He urged the South to abandon its longstanding agrarian economy for a modern economy grounded in factories, mines, and mills.

- Although textile mills and tobacco factories emerged in the South during this time, the plans for a New South largely failed. By 1900, per-capita income in the South was forty percent less than the national average, and rural poverty persisted across much of the South well into the twentieth century.

Rural agrarian poverty

An economic vision for a new south, successes and failures of the new south, what do you think.

- For more on the sharecropping system, see Amy Dru Stanley, From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Market in the Age of Slave Emancipation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

- For more on the New South, see C. Vann Woodward, The Origins of the New South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951).

- See Paul M. Gaston, The New South Creed: A Study in Southern Mythmaking (New York: Knopf, 1970); Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

- On Grady, see Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New York: Harper & Row, 1969), 1354.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Study Notes

- College Essays

AP U.S. History Notes

- Chapter Outlines

- Practice Tests

- Topic Outlines

- Court Cases

- Sample Essays

- The New South

Economic Diversification

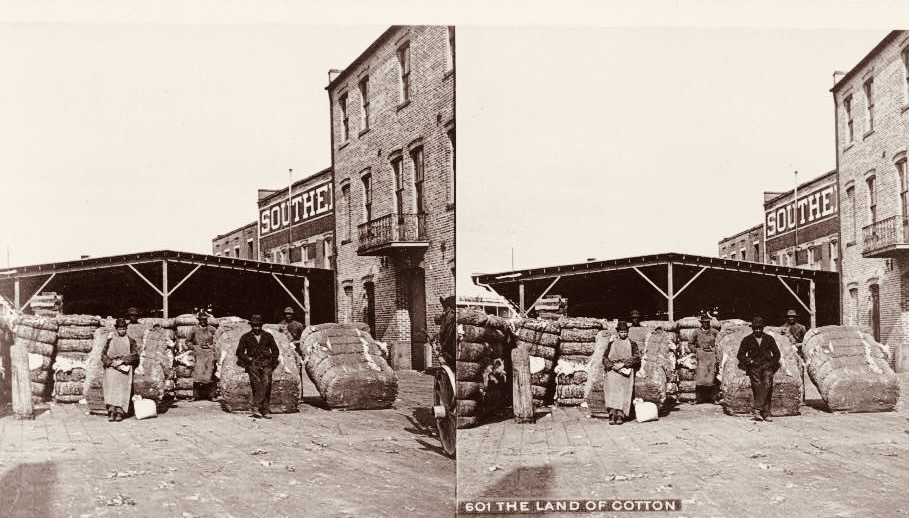

King Cotton was once the heralded “ruler” of the South, but following the Civil War this King shouldered the blame for the South’s losses. Many southern leaders believed that their reliance on one crop had made them vulnerable to the Union’s advances, and they pledged to diversify what they called the “New South.”

Henry W. Grady, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, promoted the vision for the New South at a meeting of the New England Society of New York. Grady shared an optimistic view of the New South’s potential—a strong core, economic diversity, and healthy growth over time. Grady, and other intellects of his time, foresaw an agricultural society based around the growth of several crops. They also saw the importance of following the North’s example and turning toward industrialization.

Proponents of the New South first turned to secondary crops that could thrive in southern soil. Tobacco was the second most vital crop after cotton to the pre-war South. Several factors led to a resurgence in tobacco production following the Civil War. Two new varieties, bright leaf and burley were identified, and a new method for curing tobacco so that it had less “bite” was discovered. As the Union troops came south during the war, they were introduced to this tobacco, which opened up a new export market for southern tobacco production.

In addition, rice and Louisiana cane sugar became critical elements of the South’s agricultural identity. This boom was due in large part to an agriculturalist named Seaman A. Knapp. He moved to Louisiana and used the demonstration method of agriculture education to show farmers how to select the most appropriate crops for their soil and how to care for those crops. His educational exhibitions led way to the development of a network of local and regional extension offices that supported agriculture education and production.

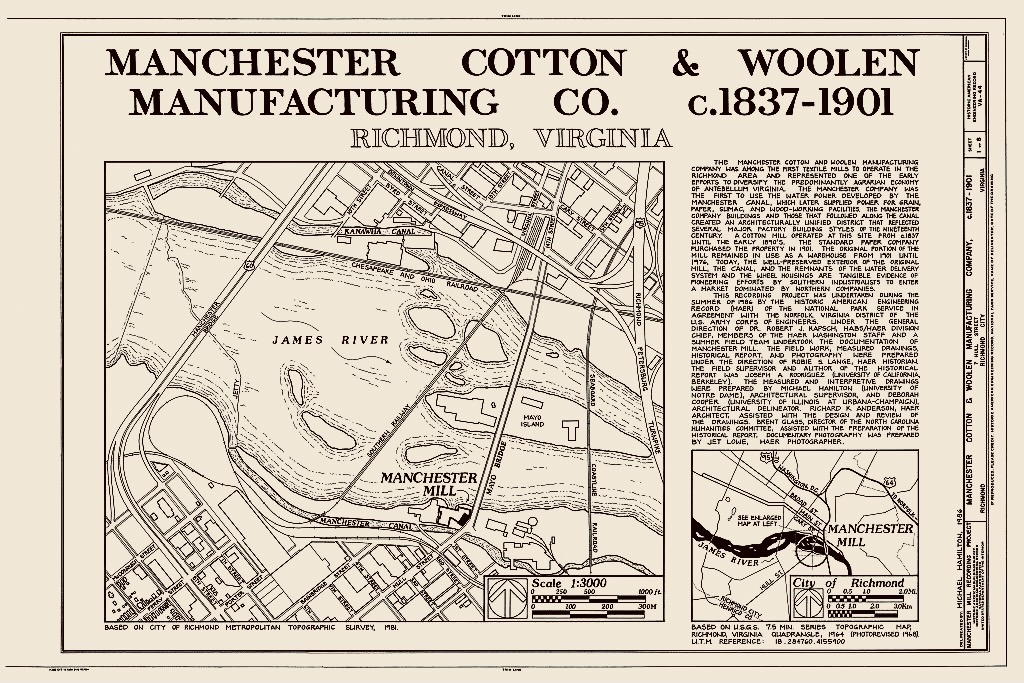

However, Southerners were not willing to turn their backs on King Cotton completely, and that proved to be a wise move. With the textile industry beginning to boom and industrialization in full force, the number of cotton mills in the south increased from 161 to 400 after the Civil War. Partly as a cause of this boom and partly as a result, cotton consumption increased from 182,000 bales to 1,479,000 per year in the late nineteenth century.

Cotton and other crops benefited from the ever-growing rail service. With additional railroad lines crossing the country, both the North and the South were able to profit from the other’s productivity. Additionally, the advent of refrigerated rail cars allowed other southern produce to reach northern markets, which further diversified the southern economy.

Field crops were not the only industry to take advantage of improved transportation. The area around Birmingham, Alabama became known for its iron, limestone, and coal production. Coal was especially important as an energy source for the trains that transported it. Between 1875 and 1900, southern coal production increased by 44 million tons per year, from 5 million to 49 million tons.

Another important energy source revitalized the South. Hydroelectricity, or electricity generated by water, was a growing force in the southeast region of the United States. This power source provided another important step in the industrialization process.

The South also offered Southern Pine trees, which were in demand for their soft, multi-use lumber—which was used in great quantities to restore homes damaged during the war. Lumber camps grew exponentially in the south after 1870, and tree cutting rose to new heights. If not for the warm climate and quick renewal of the Southern Pines, the mass destruction of these trees might have rendered the south an ecological wasteland. Fortunately, scientific forestry grew alongside the lumber camps, and the first forestry school opened in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1898.

A host of other industries also developed in the south. The lumber industry carved the way for a bustling paper commerce. Clay, glass, and stone products were in high demand. Vegetables that were not sold fresh and transported on refrigerated railway cars were canned at one of several canneries in the south. And of course, the mint julep and moonshine reputation of the South perpetuated a thriving beverage industry.

Political Changes

Along with a changing economic profile, the political atmosphere was also being transformed in the New South. With the loss of the Confederate government, southern residents turned to leaders within their community. These local leaders came to be known collectively as “Redeemers,” both for their efforts to redeem the South from being dominated by Yankees, as well as their redemption of the South from a one-crop society.

Republicans, Independents, and Populists alike called the Redeemers “Bourbons,” a derogatory label meant to imply that the Redeemers were not proactive but reactive. These critics believed that the Bourbons had learned nothing from the Civil War. As most Bourbons were Democrats, this label became entrenched in the Southern vocabulary to signify a leader of the Democratic Party.

Furthermore, the Redeemers’ detractors pointed out a major truth about this group—their true purpose was to undue the “progress” achieved by the Civil War and to reassert their dominance over blacks. Although as a group they did not participate in or advocate violence against blacks as did the KKK, the Redeemers benefited from those kinds of aggression. Their main goals were to repress blacks at the expense of whites and to increase their political power.

To that end, the Redeemers brought about a mini political revolution in the south. They believed strongly that a laissez-faire federal government would be more productive than the militarily enforced Reconstruction. This ideology was influenced by their desire to regain local control. The Redeemers also believed that education was important, but the cost should be borne by private benefactors rather than state governments. Most southern states did not have government funds for public education prior to the Civil War, and after the war the Redeemers felt that there were more pressing needs in the Reconstruction effort, such as business and industry.

Several philanthropists did come through with the funds to keep southern education afloat. London banker George Peabody was a major supporter of education through his Peabody Fund, which provided over $3 million to public schools in the south. Another philanthropist, John F. Slater, donated another $1 million, which was designated for the development and maintenance of black schools.

J.L.M. Curry, a former soldier, preacher, and educator, served as the manager of both these funds and developed many programs that are still in effect today, including teacher’s associations and summer schools. With the help of Curry’s programs, literacy increased to 88 percent for the native white population and 50 percent for the southern black population. In addition, the Redeemers’ influence led to teacher education schools, agricultural and mechanical colleges, and even black colleges.

Democrats campaigned for Congressional seats during the election of 1874 on the strength of programs such as the public education initiative and other Redeemer programs such as boards of agriculture and public health. The public bought into the platform of the Redeemers, and with their votes they gave the Democrats a majority in the House of Representatives as well as several prime seats in the Senate.

The changing mindset of the South allowed for several black politicians to emerge as leaders, if only of other blacks. South Carolina and Georgia both had black representatives in Congress throughout the late nineteenth century, although they always represented areas with a high density of black residents.

Most white people, although claiming racial superiority, wished no ill-will upon their black counterparts because they did not see them as threats to their social structure. Even as the white Redeemers were preaching racial superiority, they were practicing tolerance. For a brief period in the 1880s and 1890s, the black population was able to coexist with the white population in relative peace in the south.

Race Relations in the New South

There was a tentative peace in the south between blacks and whites, but it had severe limitations. White Southerners expected blacks to keep to themselves, to socialize and worship in separate venues, to work for white people in menial jobs and for meager wages, and to never request or demand anything, including equal rights.

When slaves were emancipated, the white South lost its labor supply and the slaves lost their shelter. Instead of owning the slaves, white men became landlords, charging high rent to slave families who often could not pay with cash. These slaves effectively became indentured servants to their former owners as they tried to pay off their debts through service—an impossible task, with the interest tacked on by the landlords.

Freedmen also encountered the difficulties of sharecropping. With little land available to purchase and few skills other than knowing how to work in the fields, former slaves participated in the sharecropping system that provided a share of the crop for the worker’s service. A similar practice was known as crop liens, in which the owner of the land—usually a freedman or a poor white man—would offer a lien on his crop to a merchant in exchange for cash or supplies. Sharecropping and crop liens were idealistic plans used by crooked bookkeepers and white land owners who kept black men in perpetual debt.

Blacks did have some allies, albeit self-serving ones. The Populist Party of the 1890s needed numbers to gain power, and blacks were numerous. Populists brought blacks en masse into their folds, even giving them prominent leadership positions. Not surprisingly, these actions stirred up the Redeemers who wanted to repress the northern influence of equality for former slaves. They also did not want to lose elections to the growing Populist Party.

Since the Fifteenth Amendment ensured that the Redeemers could not outright disenfranchise blacks, they had to be crafty. Redeemers developed voting rules for their states that were known as “literacy tests,” although they were impossible tests meant solely to weed out black voters. In addition, the Redeemers implemented poll taxes that they knew many blacks could not afford to pay. While this did eliminate most of the black vote, it also kept many poor, uneducated whites from voicing their opinions at the polls. Still, the narrow-minded Redeemers considered this a victory for the South.

The Redeemers felt further justified when Mississippi took their actions a few steps further. In 1890, at a state constitutional convention, harsher voting requirements were enacted. The first of these requirements was a residency rule, which stated that all voters had to have lived in the state’s borders for a minimum of two years. Furthermore, each voter had to prove residency within their election district for a minimum of one year. Since many blacks were transient, moving to follow jobs throughout the south, few met the strict residency requirements and lost their voting privileges under the Mississippi Plan.

Those who had maintained a proper residence in Mississippi also had to meet other requirements. All taxes had to be paid by February 1st of the voting year. Even those who met this requirement were sometimes not allowed to vote when election officials “lost” the receipt in the months prior to the election. Under Mississippi’s rules, voters also had to pass a literacy test and not have been convicted of certain crimes. Again, these rules prohibited some poor white voters from participating in elections, although the rules were sometimes not enforced for the white constituency. Regardless, it was apparent to all that the harsh rules targeted blacks.

The Mississippi Plan was adopted by seven additional states over the next 20 years. Many of these states added their own exceptions that would qualify white voters who were kept from voting under Mississippi’s rules. For example, South Carolina’s literacy requirement had a loophole that exempted voters from this requirement if they owned $300 worth of property. Likewise, Louisiana invented the “grandfather clause” in 1898, which allowed illiterates to vote if their fathers or grandfathers had been eligible to vote on January 1, 1867. This excluded blacks since blacks did not have voting rights at that time. Exceptions like this were the norm as governments attempted to exclude only black voters without violating the Fifteenth Amendment.

This exclusionary attitude infused the South. A series of seven cases before the Supreme Court ruled that discrimination against blacks by corporations or individuals was in violation of federal Civil Rights laws. However, their rulings did not prohibit states from enacting segregation laws.

Proponents of the New South took up the “Separate but Equal” battle cry. Under this agenda, segregation of blacks and whites became common as long as each had “equal” facilities. However, although blacks and whites might both have facilities that served the same purpose, such as public restrooms, railroad cars, and theater seats, the facilities were rarely equal. The railroad cars for white patrons would typically be cleaner and more comfortable than the car for blacks. The state laws legalizing this practice were known as “Jim Crow laws,” named after a black character in old minstrel shows.

These segregation laws were first tested in a case known as Plessy v. Ferguson, which went before the Supreme Court in 1896. Homer Plessy was a man with one-eighth black ancestry who was ordered to leave the whites-only railroad car. He refused the order and was arrested and later convicted of this crime. He appealed the case all the way to the highest court, but the Supreme Court validated Plessy’s conviction, and the southern states took that as a green light to enact segregation laws on a wide scale.

One Supreme Court Justice, John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky, dissented in the Plessy verdict. He believed that validating Plessy’s conviction would promote aggressive attitudes toward blacks. Such attitudes were already firmly entrenched in Southern society, and as Harlan predicted, the ruling increased the violence. Lynchings, already a common practice, hit record highs in the late 1800s, with nearly 90% of the victims being black.

Two black men, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, risked their lives to stand up against the violence and lead their fellow blacks, albeit in opposite directions. Washington, a former slave, had overcome the odds to receive an education at Hampton Institution, and he later built the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Washington encouraged blacks to keep to themselves and focus on the daily tasks of survival, rather than leading a grand uprising. He believed that building a strong economic base was more critical at that time than planning an uprising or fighting for equal rights. Washington also stated in his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech in 1895 that blacks had to accept segregation in the short term as they focused on economic gain to achieve political equality in the future.

W.E.B. Du Bois, born after the Civil War and the first African American to earn a Harvard PhD, was one of Washington’s harshest critics. He believed that Washington’s pacifist plan would only perpetuate the second-class-citizen mindset. Du Bois felt that immediate “ceaseless agitation” was the only appropriate method for attaining equal rights, especially for those he dubbed the “talented tenth” of African Americans who deserved total equality immediately. As editor of the black publication “The Crisis,” Du Bois publicized his disdain for Washington and was instrumental in the creation of the “Niagara Movement,” which later evolved into the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Eventually, Du Bois grew weary of the slow pace of racial equality in the United States. He renounced his citizenship and moved to Ghana in 1961, where he died two years later.

You just finished The New South . Nice work!

Previous Outline Next Outline

Tip: Use ← → keys to navigate!

How to cite this note (MLA)

More apush topic outlines.

- Discovery and Settlement of the New World

- Europe and the Impulse for Exploration

- Spanish and French Exploration

- The First English Settlements

- The New England Colonies

- The Middle, Chesapeake, and Southern Colonies

- Colonial Life

- Scientific and Religious Transformation

- French and Indian War

- Imperial Reorganization

- Philosophy of American Revolution

- Declaration of Independence

- The Revolutionary War

- Articles of Confederation

- The Confederation Faces Challenges

- Philadelphia Convention

- Federalists versus Antifederalists

- Development of the Two-party System

- Jefferson as President

- War of 1812

- James Monroe

- A Growing National Economy

- The Transportation Revolution

- King Cotton

- Democracy and the “Common Man”

- Nullification Crisis

- The Bank of the United States

- Indian Removal

- Transcendentalism, Religion, and Utopian Movements

- Reform Crusades

- Manifest Destiny

- Decade of Crisis

- The Approaching War

- The Civil War

- Abolition of Slavery

- Ramifications of the Civil War

- Presidential and Congressional Reconstruction Plans

- The End of Reconstruction

- Focus on the West

- Confrontations with Native Americans

- Cattle, Frontiers, and Farming

- End of the Frontier

- Gilded Age Scandal and Corruption

- Consumer Culture

- Rise of Unions

- Growth of Cities

- Life in the City

- Agrarian Revolt

- The Progressive Impulse

- The Progressive Presidents

- McKinley and Roosevelt

- Taft and Wilson

- U.S. Entry into WWI

- Peace Conferences

- Social Tensions

- Causes and Consequences

- The New Deal

- The Failures of Diplomacy

- The Second World War

- The Home Front

- Wartime Diplomacy

- Containment

- Conflict in Asia

- Red Scare -- Again

- Internal Improvements

- Foreign Policy

- Challenging Jim Crow

- Consequences of the Civil Rights Movement

- Material Culture

- JFK - John F. Kennedy

- LBJ - Lyndon Baines Johnson

- Nixon and Foreign Policy

- Nixon and Domestic Issues

- Ford, Carter, and Reagan

- Moving into a New Millennium

- 386,274 views (91 views per day)

- Posted 12 years ago

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- The Interior Lowlands and their upland fringes

- The Appalachian Mountain system

- The Atlantic Plain

- The Western Cordillera

- The Western Intermontane Region

- The Eastern systems

- The Pacific systems

- Climatic controls

- The change of seasons

- The Humid East

- The Humid Pacific Coast

- The Dry West

- The Humid–Arid Transition

- The Western mountains

- Animal life

- Early models of land allocation

- Creating the national domain

- Distribution of rural lands

- Patterns of farm life

- Regional small-town patterns

- Weakening of the agrarian ideal

- Impact of the motor vehicle

- Reversal of the classic rural dominance

- Classic patterns of siting and growth

- New factors in municipal development

- The new look of the metropolitan area

- Individual and collective character of cities

- The supercities

- The hierarchy of culture areas

- New England

- The Midland

- The Midwest

- The problem of “the West”

- Ethnic European Americans

- African Americans

- Asian Americans

- Middle Easterners

- Native Americans

- Religious groups

- Immigration

- Strengths and weaknesses

- Labour force

- Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

- Biological resources

- Manufacturing

- Foreign trade

- Roads and railroads

- Water and air transport

- The executive branch

- The legislative branch

- The judicial branch

- State and local government

- Voting and elections

- Money and campaigns

- Political parties

- National security

- Domestic law enforcement

- Health and welfare

- The visual arts and postmodernism

- The theatre

- Motion pictures

- Popular music

- The European background

- The New England colonies

- The middle colonies

- The Carolinas and Georgia

- Imperial organization

- Political growth

- Population growth

- Economic growth

- Land, labour, and independence

- Colonial culture

- From a city on a hill to the Great Awakening

- Colonial America, England, and the wider world

- The Native American response

- The tax controversy

- Constitutional differences with Britain

- The Continental Congress

- The American Revolutionary War

- Treaty of Paris

- Problems before the Second Continental Congress

- State politics

- The Constitutional Convention

- The social revolution

- Religious revivalism

- The Federalist administration and the formation of parties

- The Jeffersonian Republicans in power

- Madison as president and the War of 1812

- The Indian-American problem

- Effects of the War of 1812

- National disunity

- Transportation revolution

- Beginnings of industrialization

- Birth of American Culture

- Education and the role of women

- The democratization of politics

- The Jacksonians

- The major parties

- Minor parties

- Abolitionism

- Support of reform movements

- Religious-inspired reform

- Westward expansion

- Attitudes toward expansionism

- Sectionalism and slavery

- Popular sovereignty

- Polarization over slavery

- The coming of the war

- Moves toward emancipation

- Sectional dissatisfaction

- Foreign affairs

Lincoln’s plan

The radicals’ plan, johnson’s policy, “black codes”.

- Civil rights legislation

- The South during Reconstruction

- The Ulysses S. Grant administrations, 1869–77

- The era of conservative domination, 1877–90

- Jim Crow legislation

- Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

- Westward migration

- Urban growth

- The mineral empire

- The open range

- The expansion of the railroads

- Indian policy

- The dispersion of industry

- Industrial combinations

- Foreign commerce

- Formation of unions

- The Haymarket Riot

- The Rutherford B. Hayes administration

- The administrations of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur

- The surplus and the tariff

- The public domain

- The Interstate Commerce Act

- The election of 1888

- The Sherman Antitrust Act

- The silver issue

- The McKinley tariff

- The agrarian revolt

- The Populists

- The election of 1892

- Cleveland’s second term

- Economic recovery

- The Spanish-American War

- The new American empire

- The Open Door in the Far East

- Building the Panama Canal and American domination in the Caribbean

- Origins of progressivism

- Urban reforms

- Reform in state governments

- Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive movement

- The Republican insurgents

- The 1912 election

- The New Freedom and its transformation

- Woodrow Wilson and the Mexican Revolution

- Loans and supplies for the Allies

- German submarine warfare

- Arming for war

- Break with Germany

- Mobilization

- America’s role in the war

- Wilson’s vision of a new world order

- The Paris Peace Conference and the Versailles Treaty

- The fight over the treaty and the election of 1920

- Postwar conservatism

- Peace and prosperity

- New social trends

- The Great Depression

- Agricultural recovery

- Business recovery

- The second New Deal and the Supreme Court

- The culmination of the New Deal

- An assessment of the New Deal

- The road to war

- War production

- Financing the war

- Social consequences of the war

- The 1944 election

- The new U.S. role in world affairs

- The Truman Doctrine and containment

- Postwar domestic reorganization

- The Red Scare

- The Korean War

- Peace, growth, and prosperity

- Domestic issues

- World affairs

- An assessment of the postwar era

- The New Frontier

- The Great Society

- The civil rights movement

- Latino and Native American activism

- Social changes

- The Vietnam War

- Domestic affairs

- The Watergate scandal

- The Gerald R. Ford administration

- Domestic policy

- The Ronald Reagan administration

- The George H.W. Bush administration

- The Bill Clinton administration

- The George W. Bush administration

- Election and inauguration

- Tackling the “Great Recession,” the “Party of No,” and the emergence of the Tea Party movement

- Negotiating health care reform

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)

- Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Military de-escalation in Iraq and escalation in Afghanistan

- The 2010 midterm elections

- WikiLeaks, the “Afghan War Diary,” and the “Iraq War Log”

- The repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” the ratification of START, and the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords

- Budget compromise

- The Arab Spring, intervention in Libya, and the killing of Osama bin Laden

- The debt ceiling debate

- The failed “grand bargain”

- Raising the debt ceiling, capping spending, and the efforts of the “super committee”

- Occupy Wall Street, withdrawal from Iraq, and slow economic recovery

- Deportation policy changes, the immigration law ruling, and sustaining Obamacare’s “individual mandate”

- The 2012 presidential campaign, a fluctuating economy, and the approaching “fiscal cliff”

- The Benghazi attack and Superstorm Sandy

- The 2012 election

- The Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting

- “Sequester” cuts, the Benghazi furor, and Susan Rice on the hot seat

- The IRS scandal, the Justice Department’s AP phone records seizure, and Edward Snowden’s leaks

- Removal of Mohammed Morsi, Obama’s “red line” in Syria, and chemical weapons

- The decision not to respond militarily in Syria

- The 2013 government shutdown

- The Obamacare rollout

- The Iran nuclear deal, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, and the Ukraine crisis

- The rise of ISIL (ISIS), the Bowe Bergdahl prisoner swap, and imposition of stricter carbon emission standards

- The child migrant border surge, air strikes on ISIL (ISIS), and the 2014 midterm elections

- Normalizing relations with Cuba, the USA FREEDOM Act, and the Office of Personnel Management data breach

- The Ferguson police shooting, the death of Freddie Gray, and the Charleston church shooting

- Same-sex marriage and Obamacare Supreme Court rulings and final agreement on the Iran nuclear deal

- New climate regulations, the Keystone XL pipeline, and intervention in the Syrian Civil War

- The Merrick Garland nomination and Supreme Court rulings on public unions, affirmative action, and abortion

- The Orlando nightclub shooting, the shooting of Dallas police officers, and the shootings in Baton Rouge

- The campaign for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination

- The campaign for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination

- Hillary Clinton’s private e-mail server, Donald Trump’s Access Hollywood tape, and the 2016 general election campaign

- Trump’s victory and Russian interference in the presidential election

- “America First,” the Women’s Marches, Trump on Twitter, and “fake news”

- Scuttling U.S. participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, reconsidering the Keystone XL pipeline, and withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement

- ICE enforcement and removal operations

- The travel ban

- Pursuing “repeal and replacement” of Obamacare

- John McCain’s opposition and the failure of “skinny repeal”

- Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, the air strike on Syria, and threatening Kim Jong-Un with “fire and fury”

- Violence in Charlottesville, the dismissal of Steve Bannon, the resignation of Michael Flynn, and the investigation of possible collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign

- Jeff Session’s recusal, James Comey’s firing, and Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel

- Hurricanes Harvey and Maria and the mass shootings in Las Vegas, Parkland, and Santa Fe

- The #MeToo movement, the Alabama U.S. Senate special election, and the Trump tax cut

- Withdrawing from the Iran nuclear agreement, Trump-Trudeau conflict at the G7 summit, and imposing tariffs

- The Trump-Kim 2018 summit, “zero tolerance,” and separation of immigrant families

- The Supreme Court decision upholding the travel ban, its ruling on Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, No. 16-1466 , and the retirement of Anthony Kennedy

- The indictment of Paul Manafort, the guilty pleas of Michael Flynn and George Papadopoulos, and indictments of Russian intelligence officers

- Cabinet turnover

- Trump’s European trip and the Helsinki summit with Vladimir Putin

- The USMCA trade agreement, the allegations of Christine Blasey Ford, and the Supreme Court confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh

- Central American migrant caravans, the pipe-bomb mailings, and the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting

- The 2018 midterm elections

- The 2018–19 government shutdown

- Sessions’s resignation, choosing a new attorney general, and the ongoing Mueller investigation

- The Mueller report

- The impeachment of Donald Trump

- The coronavirus pandemic

- The killing of George Floyd and nationwide racial injustice protests

- The 2020 U.S. election

- The COVID-19 vaccine rollout, the Delta and Omicron variants, and the American Rescue Plan Act

- Economic recovery, the American Rescue Plan Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the failure of Build Back Better

- Stalled voting rights legislation, the fate of the filibuster, and the appointment of Ketanji Brown Jackson to the U.S. Supreme Court

- Foreign affairs: U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

- The Buffalo and Uvalde shootings, overturning Roe v. Wade , and the January 6 attack hearings

- Presidents of the United States

- Vice presidents of the United States

- First ladies of the United States

- State maps, flags, and seals

- State nicknames and symbols

- How did Ernest Hemingway influence others?

- What was Ernest Hemingway’s childhood like?

- When did Ernest Hemingway die?

- What did Martin Luther King, Jr., do?

- What is Martin Luther King, Jr., known for?

Reconstruction and the New South, 1865–1900

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Library of Congress - The Beginnings of American Railroads and Mapping

- HistoryNet - States’ Rights and The Civil War

- EH.net - Urban Mass Transit In The United States

- Encyclopedia of Alabama - States' Rights

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - United States

- U.S. Department of State - Office of the Historian - The United States and the French Revolution

- American Battlefield Trust - Slavery in the United States

- United States - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- United States - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Reconstruction, 1865–77

Reconstruction under abraham lincoln.

The original Northern objective in the Civil War was the preservation of the Union—a war aim with which virtually everybody in the free states agreed. As the fighting progressed, the Lincoln government concluded that emancipation of enslaved people was necessary in order to secure military victory; and thereafter freedom became a second war aim for the members of the Republican Party . The more radical members of that party—men like Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens —believed that emancipation would prove a sham unless the government guaranteed the civil and political rights of the freedmen; thus, equality of all citizens before the law became a third war aim for this powerful faction. The fierce controversies of the Reconstruction era raged over which of these objectives should be insisted upon and how these goals should be secured.

Lincoln himself had a flexible and pragmatic approach to Reconstruction, insisting only that the Southerners, when defeated, pledge future loyalty to the Union and emancipate their enslaved persons. As the Southern states were subdued, he appointed military governors to supervise their restoration. The most vigorous and effective of these appointees was Andrew Johnson , a War Democrat whose success in reconstituting a loyal government in Tennessee led to his nomination as vice president on the Republican ticket with Lincoln in 1864 . In December 1863 Lincoln announced a general plan for the orderly Reconstruction of the Southern states, promising to recognize the government of any state that pledged to support the Constitution and the Union and to emancipate enslaved persons if it was backed by at least 10 percent of the number of voters in the 1860 presidential election. In Louisiana , Arkansas , and Tennessee loyal governments were formed under Lincoln’s plan; and they sought readmission to the Union with the seating of their senators and representatives in Congress.

Recent News

Radical Republicans were outraged at these procedures, which savoured of executive usurpation of congressional powers, which required only minimal changes in the Southern social system, and which left political power essentially in the hands of the same Southerners who had led their states out of the Union. The Radicals put forth their own plan of Reconstruction in the Wade–Davis Bill , which Congress passed on July 2, 1864; it required not 10 percent but a majority of the white male citizens in each Southern state to participate in the reconstruction process, and it insisted upon an oath of past, not just of future, loyalty. Finding the bill too rigorous and inflexible, Lincoln pocket vetoed it; and the Radicals bitterly denounced him. During the 1864–65 session of Congress, they in turn defeated the president’s proposal to recognize the Louisiana government organized under his 10 percent plan. At the time of Lincoln’s assassination , therefore, the president and the Congress were at loggerheads over Reconstruction.

Reconstruction under Andrew Johnson

At first it seemed that Johnson might be able to work more cooperatively with Congress in the process of Reconstruction. A former representative and a former senator, he understood congressmen. A loyal Unionist who had stood by his country even at the risk of his life when Tennessee seceded, he was certain not to compromise with secession; and his experience as military governor of that state showed him to be politically shrewd and tough toward the enslavers. “Johnson, we have faith in you,” Radical Benjamin F. Wade assured the new president on the day he took the oath of office. “By the gods, there will be no trouble running the government.”

Such Radical trust in Johnson proved misplaced. The new president was, first of all, himself a Southerner. He was a Democrat who looked for the restoration of his old party partly as a step toward his own reelection to the presidency in 1868. Most important of all, Johnson shared the white Southerners’ attitude toward African Americans , considering Black men innately inferior and unready for equal civil or political rights. On May 29, 1865, Johnson made his policy clear when he issued a general proclamation of pardon and amnesty for most Confederates and authorized the provisional governor of North Carolina to proceed with the reorganization of that state. Shortly afterward he issued similar proclamations for the other former Confederate states. In each case a state constitutional convention was to be chosen by the voters who pledged future loyalty to the U.S. Constitution. The conventions were expected to repeal the ordinances of secession, to repudiate the Confederate debt, and to accept the Thirteenth Amendment , abolishing slavery. The president did not, however, require them to enfranchise African Americans.

Given little guidance from Washington , Southern whites turned to the traditional political leaders of their section for guidance in reorganizing their governments; and the new regimes in the South were suspiciously like those of the antebellum period. To be sure, slavery was abolished; but each reconstructed Southern state government proceeded to adopt a “ Black Code ,” regulating the rights and privileges of freedmen. Varying from state to state, these codes in general treated African Americans as inferiors, relegated to a secondary and subordinate position in society. Their right to own land was restricted, they could not bear arms, and they might be bound out in servitude for vagrancy and other offenses. The conduct of white Southerners indicated that they were not prepared to guarantee even minimal protection of African American rights. In riots in Memphis (May 1866) and New Orleans (July 1866), African Americans were brutally assaulted and promiscuously killed.

Henry Grady's Vision of the New South

When I moved to Charlotte, NC, in 1986, I visited local museums to learn about the city. One museum caught my eye – the Levine Museum of the New South . Its permanent exhibit – Cotton Fields to Skyscrapers – “uses Charlotte and its 13 surrounding counties as a case study to illustrate the profound changes in the South since the Civil War.” The “New South” – a term Atlanta newspaperman Henry W. Grady coined in a speech to the New England Society of New York on December 21, 1886 – is familiar to many American history teachers. In his speech, Grady, the first southerner to speak to the Society, claimed that the old South, the South of slavery and secession, no longer existed and that southerners were happy to witness its demise. He refused to apologize for the South’s role in the Civil War, saying, “the South has nothing to take back.” Instead, the dominant theme of Grady’s speech, according to New South historian Edward L. Ayers , “was that the New South had built itself out of devastation without surrendering its self-respect.” Tragically, Grady and most of his fellow white southerners believed maintaining their self-respect required maintaining white supremacy.

Grady, then the 46-year-old editor-publisher of the A tlanta Constitution , was one of the leading advocates of the New South creed. In New York, he won over the crowd of prominent businessmen, including J.P. Morgan and H.M. Flagler, with tact and humor. He praised Abraham Lincoln, the end of slavery, and General William T. Sherman, whom he called “an able man” although a bit “careless with fire.” Grady reassured the northern businessmen that the South accepted her defeat. He was glad “that human slavery was swept forever from American soil” and the “American Union saved.” He urged northern investment in the South as a means of cementing the reunion of the war-torn nation. He claimed progress in racial reconciliation in the South and begged forbearance by the North as the South wrestled with “the problem” of African Americans’ presence in the South. Grady asked whether New England would allow “the prejudice of war to remain in the hearts of the conquerors when it has died in the hearts of the conquered?” Grady’s audience cheered his call for political and economic reunion – albeit at the cost of African American rights.

The term “New South” was used in the 20th century to refer to other concepts. Moderate governors of the late 20th century – including Terry Sanford of North Carolina, Jimmy Carter of Georgia, and George W. Bush of Texas – were called New South governors because they combined pro-growth policies with so-called “moderate” views on race. Others used the phrase to summarize modernization in southern cities such as Charlotte, Atlanta, Richmond, and Birmingham, and the region’s increasing economic and demographic diversity. However, all uses of the term have suggested the intersection between economic development and racial justice in the South during Reconstruction, the Jim Crow Era, the Civil Rights Era and today.

This intersection included three main ideas for Henry Grady and other southern boosters of the New South in the 1880s. First, the Old South of slavery and secession was gone. Two, a New South, of unlimited economic potential welcomed investments from northern capitalists to transform the region into an industrial powerhouse. Third, and by no means last, the white South was best qualified to answer the question: what share in the new economy would be given to the formerly enslaved people?

In his New York speech, Grady described the South’s post-Civil War success, the long road ahead, and the economic disparity between the North and South. He believed this disparity threatened reunion. Though he did not deny his belief in white supremacy, Grady was not as blunt when talking to New Yorkers in 1886 as he was in Dallas, Texas, one year later. Speaking to his fellow southerners, Grady cited two problems the South faced in 1887, the “Race Problem” and the “Industrial Problem.” In addressing the “race problem,” Grady bluntly declared: “the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards – because the white race is the superior race.” Grady’s wording reveals his fear that the Black population of the South, if granted actual voting rights, could wield significant power due to its sheer size. The Texans Grady addressed in 1887 had less to fear from this perceived threat than the whites of his native Georgia. Texas whites comprised over 70% of Texas’s total population, while African Americans in Georgia constituted 47% of its population. South Carolina’s population was not majority white until 1920. “The worst thing … that could happen” Grady believed, would be an alliance between white and black voters threatening the fragile stability of the South as it continued its recovery from the Civil War.

In addressing the economic challenge, Grady bragged to his Texas audience about the South’s enormous growth. Cotton production was up. So was timber, wool, and iron. What the South now needed were Southern factories hiring southern workers that converted cotton into textiles, timber into furniture, and iron into tools.

From which racial group did Grady expect Southern factories to hire the labor they would need? In December of 1889, Grady returned to the North to deliver a speech in Boston’s Faneuil Hall on “The Race Problem in the South.” Grady argued that African Americans in the South had lost faith in the promises of Reconstruction. “Discouraged and deceived, [the Southern African American] … realized at last that his best friends are his neighbors, with whom his lot is cast and whose prosperity is bound up in his.” Did Grady expect that Black workers might eventually be hired alongside white workers in the new Southern factories? It is hard to say, because this speech was Grady’s last. Upon returning from Boston, the newspaperman developed pneumonia and died on December 23, 1889. He was only 49 years old.

American history teachers will note the similarity between Grady’s Boston rhetoric and that of the prominent southern African American leader Booker T. Washington. In a speech excerpted in Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection: Race and Civil Rights (now available in the tah.org bookstore ) known as the “ Atlanta Compromise ” speech, Washington used the metaphor of a ship desperate for fresh water and finding it after casting its buckets down where it was, unknowingly at the mouth of the Amazon River. Washington urged both blacks and whites to cast their buckets down in the South to draw up the fresh water of economic progress. But he did not suggest that blacks and whites work alongside each other in the same jobs. His Tuskegee Institute gave vocational training to Southern blacks, teaching skills that he hoped would raise the price of their labor, or even allow them to start their own businesses.

Today, Washington receives a lot of criticism for this speech. He is viewed as an accommodationist, someone willing to accept political and social discrimination in exchange for Black economic progress. However, Peter Myers’ excellent introduction to Washington’s speech in TAH’s Race and Civil Rights document volume suggests readers note Washington’s subtle rhetoric in opposition to the South’s racial status quo. One example is Washington’s advice to make friends with the surrounding white race “in every manly way.” Perhaps Washington did not believe that manly acceptance of friendly relations required African Americans to accept being denied the ballot. Arguably, if African Americans gained economic power through their skilled labor, they might eventually compel the white power structure to grant them political power as well. Perhaps Washington was dropping such hints to African Americans in his audience while seeming to reassure his white audience that Blacks had no such ambitions.

American history teachers may challenge their students to think about the concept of the New South with some of the following questions. What would Henry Grady say if he toured the Levine Museum’s exhibit and downtown Charlotte today? Would he be surprised to learn that national financial institutions such as Bank of America now make Charlotte their headquarters? Would he be surprised that the economic growth the South experienced in the late 20th century was propelled in large measure by the integration of the Southern work force? How would Grady react upon learning that the Staff Historian of the Levine Museum of the New South was Dr. Willie Griffin, an African American scholar native to the South? Would he renounce the white supremacy he endorsed during his lifetime as the political nonsense required of white public figures of his era? Would Grady claim to be proud of the racial progress the South has made, and recognize the work that remains?

Additional Resources

Theodore roosevelt launches the great white fleet, a full-throated defense of federal protection for civil rights – in 1875, join your fellow teachers in exploring america’s history..

The Writings of Carl Schurz/The New South

New York City: G. P. Putnam's Sons, pages 368–400

THE NEW SOUTH

Introduction

Twice during the last twenty years I had occasion to travel extensively over the Southern States, and to become acquainted with their condition. In 1865, a few months after the close of the civil war, I visited all of them, except Texas and Florida, and last winter all of them, except Mississippi. Each time I came into contact with a great many persons of all shades of social position and of political opinion. I improved my opportunities of inquiry and observation to the best of my ability. My object was, not to verify the correctness of preconceived notions, but to gain, by impartial investigation, a true view of things. Of the view thus obtained these pages are to give a brief and plain account.

New York , April, 1885.

In 1865, immediately after the close of the civil war, Southern society presented the spectacle of what might be called a state of dissolution. The Southern armies had just been disbanded, and the soldiers, after four years of fierce fighting, had returned home to shift for themselves. The Southern country was utterly exhausted by the war. Even where there had been no actual devastation, the product of labor had, ever since the spring of 1861, been mostly devoted to the support of armies in the field—that is, economically speaking, wasted. The money in the hands of the people had become entirely valueless. Thus the people were fearfully impoverished. The slaves, who had constituted almost the whole agricultural working force of the South, had been set free all at once. The first and very natural impulse of a large number of them was to test their freedom by quitting work and wandering away from the plantations. The country roads swarmed with them, and with a vague anticipation of a great jubilee they congregated in the towns. Thus the South was not only in distress and want, but the complete breaking up of the old labor-system and the difficulty of getting to work on a new basis made the prospect of recovery extremely dark. The negroes behaved on the whole very good-naturedly. There were few, if any, criminal excesses on their part, except pig and chicken stealing. But the negro did not yet know what to do with his freedom, and the whites had not yet learned how to treat the negroes as freemen. The former masters were easily infuriated at the new airs of their former slaves, and resorted to all sorts of means to make them work. A great many acts of violence were committed by whites on blacks. But for the interposition of the National power much more blood would have flown, and the South might have become the theater of protracted and disastrous convulsions. The Freedmen's Bureau, an institution which subsequently became discredited by abuses creeping into it, did at the beginning most valuable service in evolving some order from the prevailing chaos, and in preventing more serious catastrophes. The passions of the war were still burning fiercely, and the restored Union, which manifested itself to the defeated Southerners only in the shape of victorious “Yankee soldiers” and liberated negro slaves, was at that time still heartily detested.

The contrast between the condition of things existing then and that existing now, cannot well be appreciated without a review of the developments which have brought it forth. No greater misfortune could, in my opinion, have happened to the South at that time than the death of Mr. Lincoln. He was the only man who, taking the perplexing problem of reconstruction into his hand, would have stood between the North and the South, looked up to with equal confidence by both. His moderation and charity would not have aroused suspicion at the North, nor would his tenacity of purpose with regard to emancipation and the rights of the negro have appeared vindictive to the South. He could have prevented the passions of the war from disturbing the work of peace. While thus President Lincoln would have been the best man for the business of reconstruction, President Johnson was, perhaps, the worst imaginable. During and immediately after the war his uppermost thought was that treason must be made odious by punishing the traitors. But a few months after his accession to the Presidency he insisted with equal vehemence that the government of the late insurgent States, then in a state of dangerous confusion, must be virtually turned over to the same class of men whom but recently he had denounced as traitors fit to be hanged. His ill-balanced mind was incapable of seeing that what might be wisdom some time afterwards, was folly then. The passionate temper with which he plunged into a bitter quarrel with Congress and the Republican party about these questions produced two most unfortunate effects. The minds of Southern men were turned away from the only thing that could put them on the road of peace, order and new prosperity, namely, a prompt and sincere accommodation of their thoughts and endeavors to the new order of things. They were made to delude themselves instead with the false hope of reversing in some way the emancipation of the slaves, at least partially, by legislative contrivances—their false hopes begetting false efforts in many directions, and these efforts leading to bitter, futile and wasteful struggles, which the poor South might and should have been spared. And secondly, Mr. Johnson's proceedings made the Northern people seriously afraid of a disloyal pro-slavery reaction in the South. He irritated the majority in Congress by defiant demonstrations, and thus he caused the most intricate problem of the time to become the subject of a passionate party broil, which seemed to render men heedless as to the consequences of their doings. The Republican majority in Congress, thinking itself betrayed by the President, went faster and farther in their measures to protect the rights of the freedmen, and to procure loyal majorities in the Southern States, than they might have thought necessary to do had they not distrusted the executive. And, on the other hand, Mr. Johnson, by intemperate utterances, stirred up opposition in the South to the measures enacted by Congress. Negro suffrage was introduced, instantaneous and general, thus thrusting a mass of ignorance as an active element into the body politic, while at the same time a large number of those who had taken a more or less prominent part in the rebellion, constituting the bulk of the property and intelligence of the South, were disfranchised and debarred from active participation in public affairs.

I do not say this to criticise the reconstruction measures in general. I have always believed that they were adopted from good motives and for good purposes; that in the light of history some of them appear ill-judged, but that reconstruction was one of those tangled problems in solving which any policy that may be adopted will in some way bring forth unsatisfactory consequences, and in some respects look like a mistake. Here were a number of insurgent communities just reconquered by force of arms; in them four millions of negroes liberated from slavery by the Government against the will of their former masters; that former master class exasperated by defeat and material distress, and face to face with the former slaves; these elements, with a fierce and apparently irreconcilable antagonism between them, to be brought into peaceful and mutually beneficial relations under a new order of things, so that the weaker might be permanently safe in the presence of the stronger. That was the perplexing task to be accomplished. Was it to be done by the constant interposition of a superior power? That would have been putting off indefinitely the restoration of local self-government in the Southern States. Was it to be done by at once restoring the States to their functions, leaving all the political power in them exclusively in the hands of the whites? That would have been surrendering the late slaves, emancipated by the act of the National Government, helpless to the mercy of their former masters, whose natural desire at the time was to reduce them to slavery again. Was it to be done by arming the late slaves with political rights so as to give them the means of self-protection, and by curtailing at the same time the political rights of the late master-class, so as to weaken their means of aggression? That would expose those States to all the evils of a rule of ignorance. Thus neither of these systems, nor any mixing of them, could in all respects have worked satisfactorily as to immediate consequences. But here I have to do only with actual results.

The great mass of negro voters fell promptly into the hands of more or less selfish and unscrupulous leaders, and the scandals of the so-called carpet-bag governments followed. The Southern whites might, perhaps, have exercised a stronger influence for good upon the negroes had they at once frankly and cordially accepted the new order of things. But the old passions and prejudices did not yield so quickly, and, moreover, I repeat, President Johnson's ill-advised doings had inspired them with delusive hopes of some sort of reaction. It would be wrong to class all who during that period—from the close of the war until 1877—acted as Republican leaders in the South among the demagogues and scoundrels. There were very honorable and patriotic men among them. But, on the whole, the corruption and public robbery going on under those governments can hardly be exaggerated. A mimicry of legislation, carried on by negroes, in part moderately educated, in part mere plantation hands, and led in many cases by adventurers bent upon filling their pockets quickly—that was for years what they had of government in several Southern States.

This, of course, could not last long. A change was sure to come. Unfortunately, the carpet-bag governments were, in a measure, sustained by party spirit in Congress, while, on the other hand, the reaction against them in the South took a lawless character. The Ku-Klux organization was first started for the suppression of disorder, and then became itself an element of lawlessness. Efforts were made to overcome the negro majorities by terrorism. Negroes who were politically active, suffered cruel maltreatment. A good many murders occurred. No doubt, of the “Southern outrage” stories, some were manufactured for political effect in the North, but others were unquestionably founded on truth. When the National Government ceased to uphold the carpet-bag governments by force of arms, the “Southern outrages” of the bloody kind gradually ceased. But the efforts to keep the negroes from exercising political control continued, although by different means. Force was supplanted by ruse. In some places negro majorities were overcome by tissue ballots. In others, registration was made difficult. In others, the voting places were so arranged as to put the negroes at a disadvantage. In others, where many offices were voted for at the same time, it was provided by law that there should be a separate ballot-box for each office, and that ballots put by voters into the wrong boxes should not be counted, the effect of which was that persons unable to read, and thus to identify the boxes, would be apt to lose their votes—an arrangement working somewhat like a disqualification of illiterates. In still other places efforts were made to influence the negro vote as it is influenced here and there in the North. Thus, while at the beginning of the reconstruction period the negroes were enfranchised and a large number of whites disfranchised by law, which brought forth Republican majorities and the carpet-bag governments, subsequently the negro vote was in a large measure neutralized, first by force and then by trickery, thus, by means wrong in themselves and eventually demoralizing in effect, making Democratic majorities to put an end to the carpet-bag governments, prevent the return of negro domination and secure honesty in the administration of public affairs.

There has been, concerning these facts, much crimination and recrimination between the North and the South, partly just and partly unjust. “By your reconstruction acts,” said the South, “you subjected us to the rule of ignorant and brutal negroes led by rapacious adventurers, who mercilessly plundered us at the time when the South, exhausted and impoverished, was most in need of intelligent and honest government.” “We could not help that,” answered the North, “for we were in justice bound not to leave the emancipated negro helpless at the mercy of his former master; we had to arm him with rights, and if you had been in our places, you, as an honorable people, would have been bound to do, and would have done, the same thing.” “You have terrorized voters,” said the North, “and controlled the ballot-box by force and fraud, and thus got political power which did not belong to you.” “We could not help that,” answered the South, “for the government of combined ignorance and rapacious rascality stripped us naked, and threatened us with complete ruin. No people could have endured this. We had to get rid of negro domination at any cost, and if you had been in our places you would have done the same thing.”

While this discussion was going on, a non-political but most powerful influence asserted itself. The Southern people got to work again. Immediately after the war the average Southerner was laboring under the impression that the emancipation of the slaves had brought the whole economic machinery of the South to a complete standstill, and that, unless some system of compulsory labor were restored, there was nothing but starvation and ruin in the future. Encouraged by President Johnson's erratic manifestations, he made all sorts of reactionary attempts, but failed. He had, after all, to try what could be done under the new order of things, and he did try. Gradually he discovered that the negro as a free man would work better than had been anticipated. He discovered also that white men could, and under the pressure of circumstances would, do many kinds of work to which formerly they had not taken kindly and readily. As work proved productive, hope revived, and with hope, energy and enterprise. The Southern man became aware that his salvation did not depend upon a reversal of the new order of things, but upon a wise development of it. He found that this new order of things was opening new opportunities and calling into action new energies. So his thoughts were more and more withdrawn from the past, with its struggles and divisions and resentments, and turned upon the present and future with their common interests, hopes and aspirations. While the professional politicians of the two sections were still storming at one another, the farmers, and the merchants, and the manufacturers, and the professional men, had found something else to occupy their minds. Many of them came into contact with Northern people and met there with a much friendlier feeling than they had anticipated. It dawned upon them that this was, after all, a good country to live in, and a good government to live under, and a good people to live with. And it is this sentiment, grown up slowly but with steadily increasing strength and spreading among all classes of society, even those whose feelings against the Union were bitterest during and immediately after the war, that has made the New South as we see it to-day.

It is not my purpose here to show in detail the economic growth of the South since the war. The Northern visitor will still be struck with the enormous difference between the South and the North in the matter of wealth. Travelling from State to State and attentively looking at country and town and people, he will be apt to ask two questions. One is: How could Southern men, considering the sparseness of their population and their comparative poverty, be so foolhardy as to urge the South into that war with the rich and populous North? And the other is: How was it possible for the Southern people, considering the enormous disparity of means and resources, to maintain that war for four long years?

But, although still poor, the South is decidedly richer than it was before the war, while, of course, its wealth is differently distributed. New industries have sprung up and old ones are better developed. The mineral resources are gradually drawn to light. In the iron regions of Alabama new towns are growing up, the appearance of which reminds one of Pennsylvania. Cotton mills are multiplying. Manufacturing establishments of various kinds are rising in many places. While the sugar interest in Louisiana has much declined, other branches of agriculture, such as tobacco in North Carolina, have taken a new start. The cotton crop is constantly growing larger. The question of decisive import is no longer only how the negroes will work, for the white people themselves are working much better than before. The number of young men in the villages and small towns standing idle around the grocery corners is steadily decreasing. Among young people the tendency to devote themselves earnestly to useful and laborious occupations is becoming much more general. The poor whites of both sexes are in many places found to make industrious and faithful operatives in manufacturing establishments.

About the working habits of the colored people different judgments are heard. One planter and one manufacturer will praise them while another complains. After much investigation and inquiry, I have formed the conclusion that the employers who treat the negroes most intelligently and fairly are usually satisfied with their work, while the employers who complain most are usually those who are most complained of. The question of negro labor seems to be largely a question of management. There may be exceptions to this rule, but not enough to invalidate it. The number of colored men who have acquired property is not very large yet, but it is growing. I have seen negro settlements of a decidedly thrifty and prosperous appearance. A few colored men have become comparatively wealthy and live in some style. It is generally said of them that they are “improvident.” This is doubtless true of a large majority of them; but they are only somewhat more improvident than their former masters who used to live on next year's crop. It is a question of degrees between them. Since their emancipation they have shown much zeal for the education of their young people. Here and there this zeal is said to have cooled a little, but, as far as I have observed, it has not cooled much. Their educational facilities are still scanty in the agricultural districts, where school is kept only three months in the year. A large portion of the colored country population is therefore still lamentably ignorant.

The most unsatisfactory feature of their condition as a class is a disinclination to work, shown by many of their young people who have grown up since the abolition of slavery. There is said to be a notion spreading among them that it is the aim and end of education to enable people to get on without work. This tendency is exciting a prejudice against the education of negroes not only among certain classes of whites, but also with some of the more thrifty among the negroes themselves. I heard of a prosperous negro farmer in Alabama owning a well-stocked farm of 500 acres, worked by him with his children, who refuses to send his boys to school because learning would spoil them for farm work, and who permitted only one of his girls to learn reading and writing, so that she might be able to keep his accounts. Here is a field for missionary work, which those whose public spirit is devoted to the elevation of the colored race should keep well in view. The relation of grammar to industry must be made tangible to the young mind, as it is at the Hampton Institute and several others. The addition of industrial teaching to the common school is in this respect of especial importance. Among those who have been slaves there are a great many skillful mechanics—blacksmiths, carpenters, harness-makers, shoe makers, etc. Their sons, raised in freedom, seem to be less inclined to devote themselves to these laborious trades; and yet the negro, with his mechanical aptitudes, might, properly trained and guided, furnish the South all the handicraftsmen necessary for ordinary work. As it is, the negroes constitute, and will for a long period to come continue to constitute, the bulk of the agricultural laboring force in the principal cotton States, and every sensible Southern man recognizes them as a most valuable and, in fact, indispensable element in developing the resources and promoting the prosperity of the South. They are there to stay, and must be made the best of by just and wise treatment.

The visitor will be struck with the generally hopeful and cheery tone prevailing in Southern society. Their recovery from the disasters of the war has been more rapid than at first they expected. They are proud, and justly proud, of what they have accomplished in that direction. They are glad to have strangers observe it. Having done so much, they feel that they can do more. While business is in many respects depressed in the South, less complaint of this is heard than at the North. The general spirit prevailing in the South now is very like that characteristic of the new West: a high appreciation of the resources and advantages of the country; great expectations of future developments; a lively desire to excite interest in those things, and to attract Northern capital, enterprise and immigration; a strong consciousness and appreciation of the importance to them of their being a part of a great, strong, prosperous and united country.

The political effect of the steady growth of such feelings has been a very natural one. It is the complete disappearance of all “disloyal” aspirations. However strong their desire to destroy the Union may have been twenty years ago, I am confident, scarcely a corporal's guard of men could be found in the South to-day who would accept the disruption of the Union if it were presented to them. Those were right who predicted in the early part of the war that the abolition of slavery would not only break the backbone of the rebellion, but also remove the cause of disloyalty from the South. This it has completely accomplished. In fact, never in the history of this Republic has there been a time when there was no disunion feeling at all in this country, until now. Ever since the revolutionary period until within a few years there have always been some people who, for some reason or another, desired the dissolution of the Union, or who thought it possible, or who speculated upon its effects. Now, for the first time, there is nowhere such a wish, or such a thought, or such a speculation. By everybody the “Union now and forever” is taken for granted. The South is thoroughly cured of the mischievous dream of secession, not only by the bloody failure of its attempt, but by the constantly growing conviction that success would have been a terrible misfortune to themselves. Many a Southern man who had been active in the rebellion, said to me in conversation about the war: “It is dreadful to think what would have become of us if we had won.” They would fight now as gallantly to stay in the Union as twenty-two or three years ago they fought to get out of it. There is no doubt, should any danger threaten the Union again, the Southern people would be among its most zealous defenders.

There has been a suspicion raised at the North that this loyal garb is put on by Southern men merely for the purpose of concealing secret disloyal designs. This is absurd. Before the war they plotted and conspired, it is true. But they did not keep their purposes secret. On the contrary, they paraded them on every possible occasion. They were outspoken enough, and it was not their fault if they were not believed. Whatever may be said of our Southern people, they have never been deep dissemblers. When they say they are for the Union, they are just as honest as they were when they pronounced themselves against it.

As to the abolition of slavery, the change of sentiment is no less decided. However desperately they may have fought against emancipation, but few men can now be found in the South who would restore slavery if they could. It is said that there are some, but I have not been able to find one. The expression: “The war and the abolition of slavery have been the making of the South,” is heard on all sides. It is generally felt that new social forces, new energies, have been called into activity, which the old state of things would have kept in a torpid condition. There is, therefore, no danger of another pro-slavery movement. The relations between the colored laborer and the white employer are bound to develop themselves upon a bona-fide free-labor basis. Of the social and political relations between the two races, something more will be said below.

The distrust among Northern people as to the revival of loyal sentiments in the South, while in some cases honestly entertained, has in others been cultivated for political purposes. The question is asked: “Why, if they are loyal, do they select as their representatives men who were prominent in the rebellion? What about their reverence for Jefferson Davis?” and so on. Every candid inquirer will find to these questions a simple answer: In the “Confederate States,” a few districts excepted, nearly all white male adults entered the military service. They were all “rebel soldiers.” When after the war the Southern people had to choose public officers from among themselves, they were in many places literally confined to a choice between rebel soldiers and negroes. In other places they were not so confined. But they followed the natural impulse of preferring as their agents and representatives men who really represented them, who had been with them “in the same boat” in fair weather and in foul. This companionship in good and ill fortune has in all ages and in all countries been a strong bond to bind men together. One rebel soldier could hardly be expected to say that another rebel soldier was unworthy of public trust because of his service in the rebel army, for he would thus have disqualified himself. Nor was there necessarily any disloyalty in this—not even a remnant of it; for a rebel soldier who after the war had “accepted the situation” in perfectly good faith and sincerely resolved to accommodate himself to the new order of things, might naturally prefer as his representative another rebel soldier who had “accepted the situation” with equal sincerity, for the representation would then be more honest and, probably, more efficient.