- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Setting the stage: The two armies

- Conflict begins in Massachusetts

- Paul Revere’s ride and the Battles of Lexington and Concord

- The Siege of Boston and the Battle of Bunker Hill

- Washington takes command

- The battle for New York

- A British general surrenders, and the French prepare for war

- After a hungry winter at Valley Forge

- Setbacks in the North

- Final campaigns in the South and the surrender of Cornwallis

- Early engagements and privateers

- French intervention and the decisive action at Virginia Capes

- The end of the war and the terms of the Peace of Paris (1783)

- How did the American colonies win the war?

What was the American Revolution?

How did the american revolution begin, what were the major causes of the american revolution, which countries fought on the side of the colonies during the american revolution, how was the american revolution a civil war.

American Revolution

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Econlib - Benefits of the American Revolution: An Exploration of Positive Externalities

- Boston Tea Party Ships and Museum - American Revolution

- American Battlefield Trust - American Revolution Timeline

- Humanities LibreTexts - American Revolution

- University of Oxford - Faculty of History - American Revolutions

- American Revolution - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- American Revolution - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The American Revolution —also called the U.S. War of Independence—was the insurrection fought between 1775 and 1783 through which 13 of Great Britain ’s North American colonies threw off British rule to establish the sovereign United States of America, founded with the Declaration of Independence in 1776. British attempts to assert greater control over colonial affairs after a long period of salutary neglect , including the imposition of unpopular taxes, had contributed to growing estrangement between the crown and a large and influential segment of colonists who ultimately saw armed rebellion as their only recourse.

On the ground, fighting in the American Revolution began with the skirmishes between British regulars and American provincials on April 19, 1775 , first at Lexington , where a British force of 700 faced 77 local minutemen , and then at Concord , where an American counterforce of 320 to 400 sent the British scurrying. The British had come to Concord to seize the military stores of the colonists, who had been forewarned of the raid through efficient lines of communication—including the ride of Paul Revere , which is celebrated with poetic license in Longfellow ’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” (1861).

The American Revolution was principally caused by colonial opposition to British attempts to impose greater control over the colonies and to make them repay the crown for its defense of them during the French and Indian War (1754–63). Britain did this primarily by imposing a series of deeply unpopular laws and taxes, including the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765), and the so-called Intolerable Acts (1774).

Until early in 1778, the American Revolution was a civil war within the British Empire , but it became an international war as France (in 1778) and Spain (in 1779) joined the colonies against Britain. The Netherlands , which was engaged in its own war with Britain, provided financial support for the Americans as well as official recognition of their independence. The French navy in particular played a key role in bringing about the British surrender at Yorktown , which effectively ended the war.

In the early stages of the rebellion by the American colonists, most of them still saw themselves as English subjects who were being denied their rights as such. “Taxation without representation is tyranny,” James Otis reportedly said in protest of the lack of colonial representation in Parliament . What made the American Revolution look most like a civil war , though, was the reality that about one-third of the colonists, known as loyalists (or Tories), continued to support and fought on the side of the crown.

The American Revolution was an insurrection carried out by 13 of Great Britain ’s North American colonies that began in 1775 and ended with a peace treaty in 1783. The colonies won political independence and went on to form the United States of America . The war followed more than a decade of growing estrangement between the British crown and a large and influential segment of its North American colonies that was caused by British attempts to assert greater control over colonial affairs after having long adhered to a policy of salutary neglect .

Until early in 1778 the conflict was a civil war within the British Empire , but afterward it became an international war as France (in 1778) and Spain (in 1779) joined the colonies against Britain . Meanwhile, the Netherlands , which provided both official recognition of the United States and financial support for it, was engaged in its own war against Britain ( see Anglo-Dutch Wars ). From the beginning, sea power was vital in determining the course of the war, lending to British strategy a flexibility that helped compensate for the comparatively small numbers of troops sent to America and ultimately enabling the French to help bring about the final British surrender at Yorktown in 1781.

The American colonies fought the war on land with essentially two types of organization: the Continental (national) Army and the state militias . The total number of the former provided by quotas from the states throughout the conflict was 231,771 soldiers, and the militias totaled 164,087. At any given time, however, the American forces seldom numbered over 20,000; in 1781 there were only about 29,000 insurgents under arms throughout the country. The war was therefore one fought by small field armies. Militias, poorly disciplined and with elected officers, were summoned for periods usually not exceeding three months. The terms of Continental Army service were only gradually increased from one to three years, and not even bounties and the offer of land kept the army up to strength. Reasons for the difficulty in maintaining an adequate Continental force included the colonists’ traditional antipathy toward regular armies, the objections of farmers to being away from their fields, the competition of the states with the Continental Congress to keep men in the militia , and the wretched and uncertain pay in a period of inflation .

By contrast, the British army was a reliable steady force of professionals. Since it numbered only about 42,000, heavy recruiting programs were introduced. Many of the enlisted men were farm boys, as were most of the Americans, while others came from cities where they had been unable to find work. Still others joined the army to escape fines or imprisonment. The great majority became efficient soldiers as a result of sound training and ferocious discipline . The officers were drawn largely from the gentry and the aristocracy and obtained their commissions and promotions by purchase. Though they received no formal training, they were not so dependent on a book knowledge of military tactics as were many of the Americans. British generals, however, tended toward a lack of imagination and initiative , while those who demonstrated such qualities often were rash.

Because troops were few and conscription unknown, the British government, following a traditional policy, purchased about 30,000 troops from various German princes. The Lensgreve (landgrave) of Hesse furnished approximately three-fifths of that total. Few acts by the crown roused so much antagonism in America as that use of foreign mercenaries .

History Homework Help

Students often search for “do my history homework” because history can be complex and time-consuming. We understand that balancing schoolwork with other responsibilities can be challenging. That’s why AssignmentBro offers personalized support tailored to your specific needs. Our experts will help you understand historical events, analyze primary sources, and craft well-structured essays and reports.

We guarantee top-quality, plagiarism-free work delivered on time. Our team is dedicated to helping you succeed academically and gain a deeper understanding of history. Don’t let history homework stress you out. Reach out to AssignmentBro today and say goodbye to your worries. Just tell us, “ do my assignment ,” and we’ll take care of the rest. Boost your grades and confidence with our expert history homework help.

- Business and Entrepreneurship

- -------------------

- African-American Studies

- Anthropology

- Architecture

- Art, Theatre and Film

- Communication Strategies

- Computer Science

- Criminology

- Engineering

- Environmental Issues

- International and Public Relations

- Law and Legal Issues

- Linguistics

- Macroeconomics

- Mathematics

- Microeconomics

- Political Science

- Religion and Theology

Say Hello To Our History Homework Writers

How come we’re so confident in our team? Each of our writers undergoes:

- Diplomas and certificates verification

- Composite English test

- Academic writing test task

- Thorough performance monitoring

Result? An extremely high concentration of top-notch professionals per square foot.

Do My History Homework: Our Features

How To Order History Assignment Help?

Your AssignmentBro Forever for History Homework Help

What is AssignmentBro? It is your personal US history helper with a strong crew of professionals working here. We provide students with our assistance across all subjects, including astronomy homework help for the affordable costs. If you’re exhausted with the university homework, combine work with study and don’t have additional time for deep research or just have an eventful social life, you’re where you should be! AssignmentBro’s willing to help you!

History Topics, Popular Among Students

Here are some topics customers ask to make their assignments on the most:

- Great Depression

- Relationships Between Mexico and America

- Ancient American History

- Revolutionary War

- Second World War and Its Impact on American Society

- Industrialization

- Women’s Suffrage

It’s only a small part of the World history topics’ huge range. Our writers can provide United States history help on any issue you require.

Up to Scratch History Help

| Subject | History 📜 |

| Types of assistance | Writing, editing, proofreading, and PowerPoint presentation help. |

| Periods | Ancient Times, Colonization, Revolution, Expansion and Reform, Civil War, World Wars, Modern history. |

| Available writers | 30+ experts online. |

Want your perfect papers for the relatively cheap prices? Check what AssignmentBro homework helper can offer:

- Professional Writers . Our hiring strategy is far from ‘cool-down’. We pick only brilliant experts in different areas. Thus, you can be sure about the quality of your history homework.

- No-plagiarism Policy. What? Copy-paste? Didn’t hear about it here. We run all the documents through the plagiarism checker before sending them to you.

- Revisions and Refunds . Sometimes customers want writers to fix some nuances of the papers after the receiving. And we’re completely ok with such situations. Our clients get an option of free never-ending revisions in such a case. If they aren’t satisfied even after fixing, we make a full refund.

- 24/7 Support. Our support crew is available at any time of the day. If you’re in a different time zone, you will still get all the answers to your questions within a couple of minutes.

AssignmentBro expert writers can help with related subject for example science homework help .

Don’t Throw Away Your Shot To Get The Best US History Help

Can’t find a proper tutor for your needs? You already have him! AssignmentBro is the perfect place for asking for help with history assignments. Our platform is user-friendly and our writers are ready to cooperate with everyone. Our goal number one is to make as many students as possible happy. If you want A+ papers permanently, and, at the same time, don’t want to go crazy from the sleepless nights, ask AssignmentBro for assistance right now!

Over 1000 students entrusted Bro

- Statistics Homework Help

- Do My Math Homework

- Chemistry Homework Help

- Nursing Assignment Help

- Law Assignment Help

- Accounting Assignment Help

- English Homework Help

- Management Assignment Help

- Physics Homework Help

- MBA Assignment Help

- Economics Homework Help

- Engineering Assignment Help

- Science Homework Help

- HND Assignment Help

- Finance Homework Help

- Marketing Assignment Help

- Biology Assignment Help

- Business Assignment Help

- Psychology Homework Help

- Geography Assignment Help

- Econometrics Assignment Help

- HR assignment help

- Computer Science Homework Help

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

American Revolution

The Revolutionary War waged by the American colonies against Britain influenced political ideas and revolutions around the globe, as a small fledgling nation won its freedom from the greatest military force of its time.

Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War (1775‑1783) arose from growing tensions between residents of Great Britain’s 13 North American colonies and the colonial government. The American colonists, led by General George Washington, won political independence and eventually formed the United States of America.

Battles of Lexington and Concord

Lead‑Up to the Battles of Lexington and Concord Starting in 1764, Great Britain enacted a series of measures aimed at raising revenue from its 13 American colonies. Many of those measures, including the Sugar Act, Stamp Act and Townshend Acts, generated fierce resentment among the colonists, who protested against “taxation without representation.” Boston, the site […]

Dunmore’s Proclamation

Loyalist Governor Sought to Expand His Troops The proclamation was months in the making, as Dunmore was in a vulnerable position as throngs of rebels filled the Virginia capital of Williamsburg, prompting the loyalist governor to depart for Norfolk. Worsening matters for him was that many of his forces had deserted him, leaving him with […]

Continental Congress

Britain and the Imperial Crises Throughout most of colonial history, the British Crown was the only political institution that united the American colonies. The Imperial Crises of the 1760s and 1770s, found England saddled with crippling debt, incurred in large part by wars such as the French and Indian War. The British government responded by […]

Global Impact of the American Revolution

The American Revolution influenced political ideals and revolutions across the globe.

American Revolution History

Did you know that Paul Revere didn’t ride alone, and there were women on the Revolutionary War battlefields? Find out more about the war’s lesser‑known patriots.

Boston Massacre Sparks a Revolution

The shooting of several men by British soldiers in 1770 inflames passions in the colonies.

The Tea Act of 1773, an act of Great Britain’s Parliament, was the catalyst for some of the most important moments of the lead‑up to the Revolutionary War.

7 Events That Enraged Colonists and Led to the American Revolution

Colonists didn’t just take up arms against the British out of the blue. A series of events escalated tensions that culminated in America’s war for independence.

The Declaration of Independence Was Also a List of Grievances

The document was designed to prove to the world (especially France) that the colonists were right to defy King George III’s rule.

7 Hard‑Fought Battles That Helped Win the American Revolution

While the British were often better equipped and trained, these events proved critical in ultimately securing Americans’ victory in the war.

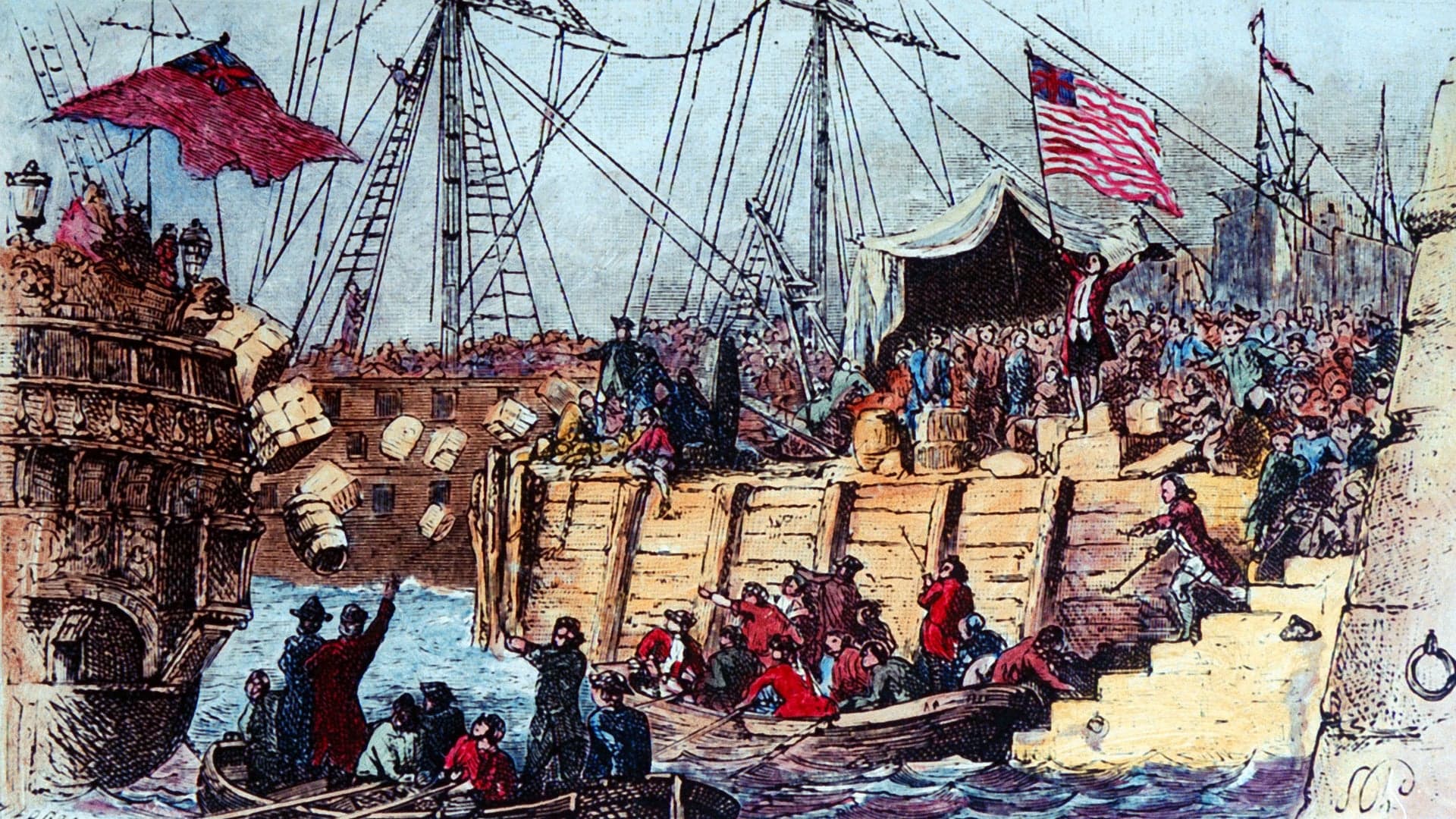

7 Surprising Facts About the Boston Tea Party

For starters, the colonists weren’t protesting higher taxes on tea.

This Day in History

U.S. Army founded

This Day in History Video: What Happened on July 4

This Day in History Video: What Happened on September 21

This Day in History Video: What Happened on December 16

This Day in History Video: What Happened on October 19

Congress issues a “declaration on the causes and necessity of taking up arms”.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

The American Revolutionary War, Essay Example

Pages: 6

Words: 1771

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

The American Revolutionary War, also referred to as the American War of Independence, was commenced by the thirteen American protectorates’ delegates in opposition to Great Britain. The thirteen colonies objected to the congress’s taxation guidelines and the absence of colonial representatives. The conflicts between expatriate militiamen and British multitudes started in April 1775 in Lexington. Before beginning the preceding summer, the protesters had instigated an all-out war to gain their liberation. The French offered their support to the Continental militia and compelled the British to capitulate in 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia. Although the Americans successfully achieved their liberation, the War did not officially conclude till 1783. The War was deemed an internal battle within the Great Britain Empire until 1778, after which it advanced to a global war and involved other nations[1]. The initial objective of the American colonists was to gain control of their affairs, particularly tax regulations. The Britain Empire had the most control over the thirteen colonies’ affairs until 1776 when the American colonies attained independence[2]. However, the War lasted until 1783 and turned out with British multitudes losing influence on the colonies due to their incompetence. This paper looks at the reasons as to why the American War of Independence turned out the way it did.

The American colonies believed that the British administration’s role was to safeguard their liberties and freedoms. However, after the Indian and French War, the colonists began experiencing several occasions of violation of their sovereignty and privileges by the British government. The lack of colonist representatives within the parliament made them believe that they were not eligible for taxation. This was because British citizens were granted the liberty to choose their parliamentary representatives who had the power to vote on suggested taxes. The revolution’s progression resulted in a government’s formation by the Americans founded on the Confederation Articles’ provisions, which received ratification in 1781. The formulated government provided for individual states’ creation since most Americans did not believe in a robust centralized authority as they were fighting for liberation from Great Britain. The notion established by this provision was to retain power and prevent their subjection to effective controls separate from their states. However, this governmental regime proved to be incompetent and resulted in the Constitutional Convention in 1787 in Philadelphia.

During the onset of the War, the British had more militiamen in their troops. The armed forces’ growth was slow initially. After the Prime Minister, Lord North, received information on French troops’ augmentation, more individuals were recruited and added to existing units. However, the effort made by the British military changed drastically after the French involvement in the War[3]. A common belief on why Britain lost to the American colonies is due to their overconfidence and arrogance. However, the British army knew how tough it would be to conquer the rebellion. They had no particular hope of overcoming America due to the territory’s largeness and the meager nature of attainable resources. Given this, they established a tactic that they anticipated would produce disproportionate outcomes due to diligent efforts. This plan was referred to as the Hudson strategy since it integrated activities across the Hudson River, which runs up to Canada from New York. The British army anticipated to separate New England rebels from the southern and Middle colonies that were moderate. Britain was of the view that such isolation would strangle the American rebels’ right to submission[4]. The main setback was the poor execution of the plan and not the strategy itself. The outstanding leadership skills portrayed by George Washington and the British leader’s strategic errors promoted the conquest of the American colonies.

The British tactic aimed at destroying the Northern rebellion, and they came close to defeating the Continental militiamen several times. However, the triumphs at Princeton and Trenton in 1776 and the beginning of 1777 reestablished patriotic expectations. Further, the Saratoga triumph, which stopped the British from advancing from Canada, resulted in a French intervention in the colonies’ support[5]. The beginning of the War saw the absence of an expert army for the American colonies. The militiamen were casually armed, underwent slight training, and lacked uniforms. The militia units occasionally served and did not go through adequate training nor learn the discipline expected from skilled soldiers. Furthermore, native militias were hesitant to leave their homes, thus making them unreachable for comprehensive operations. The continental army endured drastically due to the absence of efficient training schedules and inexperienced sergeants and officers.

The British army had successfully operated in America before the Revolutionary War. It was tempting for the British to assume that similar logistics would apply during the American Revolution. There were differences in the British structure of logistical management[6]. The logistics during the eighteenth century were accountable to several executive sectors, including the Navy Board, the War Office, and the Board of Ordnance. However, the most considerable portion of accountability rested on the treasury. The revolution onset collapsed this system drastically. An example of patriotic boards’ action was cutting off the provisions intended for the Boston army. This significantly impacted their involvement in the War. The situation made it necessary for the British military to seek Europe’s assistance since preserving massive armed forces over great distances was largely difficult. It would take three months for ships to convey across the Atlantic Ocean; thus, briefings emanating from London were mostly nonoperational when they arrived. Before the War, American colonies were autonomous political and socio-economic entities and lacked a distinct region of definitive strategic significance. This illustrates that a city’s collapse in America did not stop wars all the more so after the forfeiture of main commune areas such as New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia.

The British influence relied on the Noble Navy, whose supremacy allowed for their resupply of expeditionary powers while averting admittance to adversary ports. However, most of the American populace was agricultural, received France’s support, and barricade runners grounded within the Dutch Caribbean, hence protecting their economy. The American colonies’ terrestrial extent and inadequate human resources indicated the British incompetence to concurrently carry out military processes and inhabit the region while lacking local maintenance. The campaign held in 1775 portrayed how Britain overrated their troops’ capabilities and undervalued the colonial militiamen, making it necessary to reassess their strategies and tactics. However, it guaranteed the Patriots an opportunity to undertake resourcefulness, which led to the rapid loss of British influence over most colonies.

Several intercontinental contexts of the American Revolution contributed to its outcomes. The first context was Britain’s political agenda[7]. The British avoided the intervention of foreign states during the War since it would lower their chances of conquering the battle. They isolated themselves from other allies since they could not afford to reimburse them[8]. Additionally, Britain was becoming extremely powerful and failed to locate partners who would threaten the Spanish or French Home Front. The second aspect was France’s plan to reduce British influence and avenge them. The French also offered their support to the American colonies in numerous ways. They provided material backing in May 1776, established a treaty of Commerce and Amity in February 1778, which resulted in recognition and trade, and formed an alliance treaty in 1778 for a military agreement[9]. There was martial intervention between the French and American colonies. The third international aspect of the War was Spain’s plan, which integrated numerous tactics. Their main objectives were to bring back Gibraltar and lower British influence and authority. Spain formed a military intervention in 1779 and joined the War, not as America’s allies, but France’s supporters.

The fourth aspect was the circumstances in Holland. The Anglo-Dutch associations turned sour as the Dutch were not in support of Britain due to their trade relations with France and America. This resulted in War raging between Britain and Holland. The British anticipated doing away with Holland’s support to the French and the rebels, which was unsuccessful[10]. The enlightenment notions also promoted the turn of events during the War. The enlightenment was a scientific and cultural movement initiated in Europe that emphasized aspects of rationality and reason over misconception. Thomas Hobbes, an English theorist, developed the social contract idea. Additionally, John Locke, another theorist, established that individuals have the liberty to the preservation of life, property, and other additional attributes from the governing administration. These notions influenced the American Revolution’s outcomes as the colonists were dedicated to achieving the right to liberty, life, and the search for contentment.

The primary revolution outcome was the liberty of the thirteen once British protectorates in North America. Additionally, the revolution served as a philosophical refinement of monarchists in the thirteen former British protectorates. Most of these royalists were forced to move to Canada after the War, and among them were several slaves who fought as British allies in the War. The Revolutionary War had several consequences, including the death of approximately 7,200 Americans due to the War. An additional 10,000 succumbed to disease and similar exposure while roughly 8,500 perished in the British jails[11]. Another consequence was the escape of some slaves in Georgia and South Carolina. The nations also implemented transcribed constitutions that ensured religious liberty, heightened the powers and form of the legislature, transformed inheritance regulations, and advanced the tax system.

[1] Hoffman, Ronald, and Peter J Albert. 1981. “France and the American Revolution Seen as Tragedy”. In Diplomacy And Revolution , 73-105. Charlottesville: Published for the United States Capitol Historical Society by the University Press of Virginia.

[2] Spring, Matthew H. 2014. “The Army’s Task”. In With Zeal And With Bayonets Only, 3-23. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

[3] Resch, John, and Walter Sargent. 2007. “Incompatible Allies”. In War & Society In The American Revolution , 191-214. Northern Illinois University Press.

[4] Moyer, Paul, History 309. “The International Dimensions Of The Revolutionary War”. Presentation.

[5] Resch, John, and Walter Sargent. 2007. “Incompatible Allies”. In War & Society In The American Revolution , 191-214. Northern Illinois University Press.

[6] Bowler, Arthur. n.d. “Logistics and Operations in the American Revolution”. In Logistics And The Failure Of The British Army In America, 1775-1783, 55-71.

[7] Moyer, Paul, History 309. “The International Dimensions Of The Revolutionary War”. Presentation.

[8] Resch, John, and Walter Sargent. 2007. “Incompatible Allies”. In War & Society In The American Revolution , 191-214. Northern Illinois University Press.

[9] Tiedemann, Joseph S, Eugene R Fingerhut, and Robert W Venables. 2009. “Loyalty is Now Bleeding in New Jersey, Motivations and Mentalities of the Disaffected”. In The Other Loyalists , 45-77. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

[10] Hoffman, Ronald, and Peter J Albert. 1981. “France and the American Revolution Seen as Tragedy”. In Diplomacy And Revolution , 73-105. Charlottesville: Published for the United States Capitol Historical Society by the University Press of Virginia.

[11] Spring, Matthew H. 2014. “The Army’s Task”. In With Zeal And With Bayonets Only, 3-23. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Roots of Modern Life Under Aristotle's, Essay Example

Energy Efficiency Optimization, Research Paper Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Relatives, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 364

Voting as a Civic Responsibility, Essay Example

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

Top of page

Collection George Washington Papers

The american revolution.

A timeline of George Washington's military and political career during the American Revolution, 1774-1783.

1774 | 1775 | 1776 | 1777 | 1778 | 1779 | 1780 | 1781 | 1782 | 1783

July 6-18, 1774

Attends meetings in Alexandria, Virginia, which address the growing conflict between the Colonies and Parliament. Washington co-authors with George Mason the Fairfax County Resolves, which protest the British "Intolerable Acts"--punitive legislation passed by the British in the wake of the December 16th, 1773, Boston Tea Party. The Fairfax Resolves call for non-importation of British goods, support for Boston, and the meeting of a Continental Congress.

July 18, 1774

The Resolves are presented to the public at the Fairfax County Courthouse. Fairfax Resolves

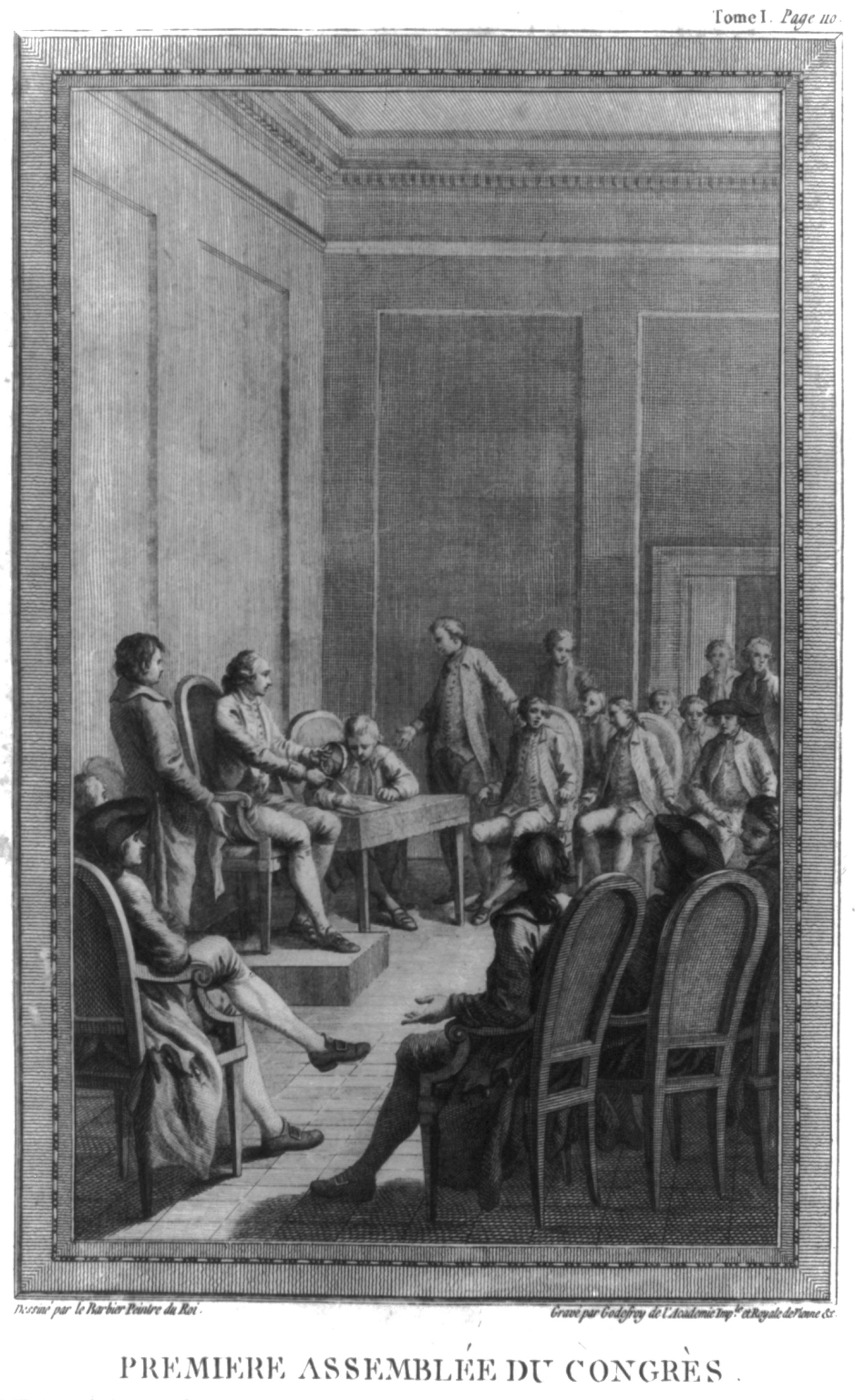

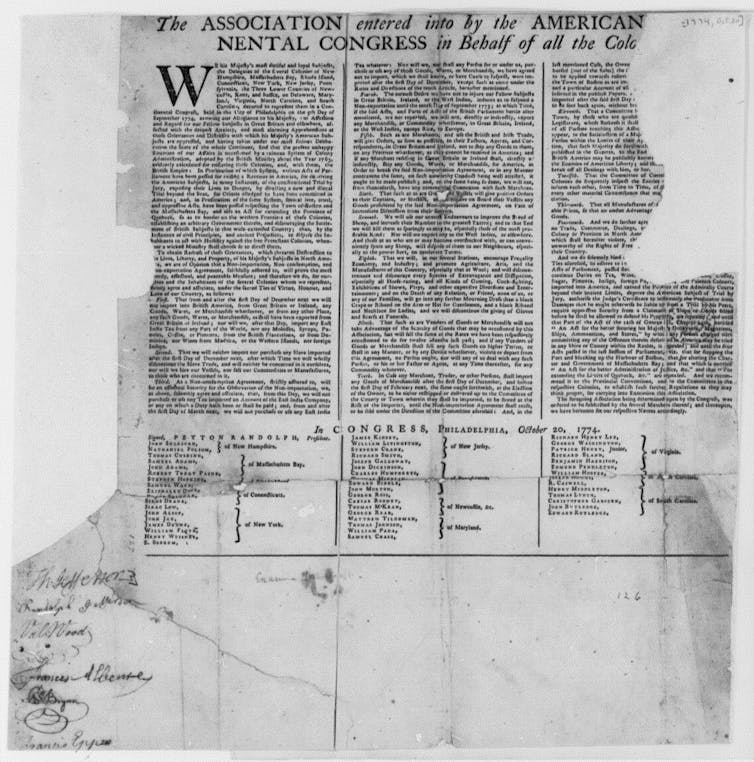

September 5 - October 26, 1774

The First Continental Congress meets in Philadelphia. Washington serves as a delegate from Virginia.

October 9, 1774

While attending the First Continental Congress, Washington responds to a letter from Captain Robert Mackenzie, then in Boston. Mackenzie, a fellow Virginia officer, criticizes the behavior of the city's rebellious inhabitants. Washington sharply disagrees and defends the actions of Boston's patriots. Yet, like many members of Congress who still hope for reconciliation, Washington writes that no "thinking man in all North America," wishes "to set up for independency." George Washington to Robert Mackenzie, October 9, 1774

April 19, 1775

The battles of Lexington and Concord.

Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, and Benedict Arnold and the Massachusetts and Connecticut militia, take Fort Ticonderoga on the western shore of Lake Champlain, capturing its garrison and munitions.

May 10, 1775

The Second Continental Congress convenes. Washington attends as a delegate from Virginia.

May 18, 1775

Congress learns of the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and that military reinforcements from Britain are on their way to North America.

May 25, 1775

British generals William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne arrive in Boston with reinforcements for military commander Thomas Gage. July 12, Howe's brother Admiral Richard Howe will arrive in North America with a large fleet of warships.

May 26, 1775

Congress resolves to begin preparations for military defense but also sends a petition of reconciliation, the "Olive Branch Petition," to King George III.

June 12, 1775

British General Thomas Gage declares Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. He offers amnesty for all who lay down their arms--except for Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

June 14, 1775

Debate begins in Congress on the appointment of a commander in chief of Continental forces. John Hancock expects to be nominated but is disappointed when his fellow Massachusetts delegate, John Adams, suggests George Washington instead as a commander around whom all the colonies might unite. June 15, Washington is appointed commander in chief of the Continental Army. The forces from several colonies gathered in Cambridge and Boston become the founding core of that army.

June 16, 1775

Washington makes his acceptance speech in Congress. As a gesture of civic virtue, he declines a salary but requests that Congress pay his expenses at the close of the war. On July 1, 1783, Washington submits to the Continental Board of Treasury his expense account. George Washington's Revolutionary War Expense Account

June 17, 1775

The battle of Bunker or Breeds Hill.

June 27, 1775

Congress establishes the northern army under the command of Major General Philip Schuyler, and to prevent attacks from the north, begins planning a campaign against the British in Canada.

July 3, 1775

Washington assumes command of the main American army in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where it has been laying siege to British-occupied Boston.

July 4, 1775

Washington issues general orders to the army, announcing that they and those who enlist "are now Troops of the United Provinces of North America," and expressing hope "that all Distinctions of Colonies will be laid aside; so that one and the same Spirit may animate the whole, and the only Contest be, who shall render, on this great and trying occasion, the most essential service to the Great and common cause in which we are all engaged." General Orders, July 4, 1775

July 6, 1775

Congress approves and arranges for publication of A Declaration by the Representatives of the United Colonies of North America.... , written by Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson. Unlike Jefferson's Declaration of Independence of a year later, this document blames Parliament primarily and King George III secondarily for the Colonies' grievances.

July 12, 1775

Congress establishes commissions on Indian relations for the north, middle, and southern regions of the Colonies.

July 31, 1775

Congress rejects a proposal for reconciliation from the North Ministry. The proposal is sent to prominent private individuals instead of to Congress and falls short of independence.

August 1775

Washington establishes a naval force to battle the British off the New England coast and to prey on British supply ships.

August 23, 1775

King George III declares all the Colonies to be in a state of rebellion.

September 6, 1775

Washington's final draft of his "Address to the Inhabitants of Canada" calls for their support in the war for independence. Benedict Arnold will carry the Address on his march through the Maine wilderness to take Quebec. On the same day, Washington calls for volunteers from among his own army to accompany Benedict Arnold and his Virginia and Pennsylvania militia. Address to the Inhabitants of Canada, September 6, 1775 | George Washington's Revolutionary War Expense Account: September 28, 1775 , expenses for printing copies of the "Address" by Ebenezer Gray

September 28, 1775

Washington writes the Massachusetts General Court, introducing an Oneida Chief who has arrived at the Continental army encampment in Cambridge. Washington believes he has come "principaly to satisfy his Curiosity." But Washington hopes he will take a favorable report back to his people, with "important Consequences" to the American cause. The Oneidas are members of the Iroquois or Six Nation League of the upper New York region. To preserve their lands from incursions by either side, the League attempts a policy of neutrality. The Revolution, however, causes a civil war among the Iroquois, and the Oneidas are one of the few tribes to side with the Americans. George Washington to Massachusetts General Court, September 28, 1775

October 4, 1775

Washington writes Congress about the treasonous activities of Dr. Benjamin Church. Church, a leading physician in Boston, has been active in the Sons of Liberty, in the Boston Committee of Correspondence, and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety and Provincial Congress. At the same time, however, he has been spying for British military commander of Boston Thomas Gage. In his October 5 letter to Congress, Washington describes how one of Church's letters to Gage was intercepted. Eventually Church is tried by several different courts and jailed. In 1778, he is allowed to go into exile. He is lost at sea on his way to the West Indies. Congress passes more severe penalties for treason as a result of this case. George Washington to Congress, October 5, 1775

October 18, 1775

A British squadron under command of Lieutenant Henry Mowat bombards and burns the Falmouth (Portland, Maine) waterfront after providing inhabitants time to evacuate the area. Washington writes the governors of Rhode Island and Connecticut, October 24, enclosing an account of the attack by a Falmouth citizen, Pearson Jones, and severely criticizing the British for not allowing enough time for inhabitants to remove their belongings. When Mowat briefly comes ashore on May 9, he is captured by Brunswick, Maine, citizens, but they are persuaded by Falmouth town leaders to let him go. Pearson Jones's Account of the Destruction of Falmouth, October 24, 1775

October 24, 1775

Washington writes to the Falmouth, Maine, Safety Committee to explain why he cannot send the detachment from his army they request. Throughout the war, the British attempt to lure Washington into committing his whole army to battles he cannot win, or, into weakening it by sending out detachments to meet British incursions. George Washington to Falmouth, Maine, Safety Committee, October 24, 1775

November 1, 1775

Congress learns of King George's rejection of the Olive Branch Petition, his declaration that the Colonies are in rebellion, and of reports that British regulars sent to subdue them will be accompanied by German mercenaries.

November 5, 1775

General Orders, Washington reprimands the troops in Cambridge for celebrating the anti-Catholic holiday, Guy Fawkes Day, while Congress and the army are attempting to win the friendship of French Canadian Catholics. He also writes commander of the northern army, Philip Schuyler, on the importance of the acquisition of Canada to the American cause. George Washington, General Orders, November 5, 1775 | George Washington to Philip Schuyler, November 5, 1775

December 31, 1775

Benedict Arnold and Richard Montgomery and their forces join on the St. Lawrence River to attack Quebec. Montgomery has recently taken Montreal and has replaced Philip Schuyler, then weakened by illness, as commander of the northern army. During the attack, Montgomery is killed immediately and Arnold is wounded. The attack fails, but Arnold follows it with a siege of the city, which also fails. On June 18, 1776, Arnold will be the last to retreat from Canada and the still undefeated city of Montreal, then commanded by Sir Guy Carleton. On January 27, Washington will write Arnold to commiserate with him on the failure of the campaign. Arnold is commissioned a brigadier general in the Continental Army on January 10, 1776. George Washington to Benedict Arnold, January 27, 1776

January 7, 1776

Washington writes Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull from Cambridge. Washington has "undoubted intelligence" that the British plan to shift the focus of their campaign to New York City. The capture of this city "would give them the Command of the Country and the Communication with Canada." He intends to send Major General Charles Lee to New York to raise a force there to defend the City. George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, January 7, 1776 | George Washington to Charles Lee, January 30, 1776

February 4, 1776

Major General Charles Lee and British General Henry Clinton both arrive in New York City on the same day. Lee writes that Clinton claims "it is merely a visit to his Friend Tryon" [William Tryon, the former royal governor of New York]. "If it is really so, it is the most whimsical piece of civility I ever heard." Clinton claims that he intends heading south where he will receive British reinforcements. Lee writes, "to communicate his plan to the Enemy is too novel to be creditted." Clinton does eventually head south, receiving his reinforcements at Cape Fear on March 12.

March 27, 1776

The British evacuate Boston. Washington writes Congress with the news of this and of his plans for detaching regiments of the Army in Cambridge to New York under Brigadier General John Sullivan, with the remainder of the Army to follow. George Washington to Congress, March 27, 1776

April 4, 1776

Washington leaves Cambridge, Massachusetts with the Army and by April 14 is in New York.

April 17, 1776

Washington writes the New York Committee of Safety. New York has not yet come down decisively on the side of independence, and merchants and government officials are supplying the British ships still in the harbor. Washington, angry at the continued communication with the enemy, asks the Committee if the evidence about them does not suggest that the former Colonies and Great Britain are now at war. He insists that such communications should cease. George Washington to the New York Safety Committee, April 17, 1776

South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia begin campaigns to crush the Overhill Cherokees. The British Proclamation of 1763 limited frontier settlement to the eastern side of the Appalachians to prevent incursions into Indian lands and resulting costly wars. But the Proclamation has not been observed and hostilities between white settlers and Cherokees have grown over the decades. Supplied with arms by the British, the Overhill Cherokees begin a series of raids. State militias respond with expeditions and raids of their own. By the Treaty of DeWitt's Corner, May 1777, the Cherokees cede almost all their land in South Carolina. Similar treaties result in land cessions to North Carolina and Virginia.

June 4, 1776

A British fleet under command of Commodore Sir Peter Parker with Clinton and his reinforcements approaches the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina.

June 28, 1776

The British begin bombardment of Fort Sullivan in Charleston harbor. Failing to take the Fort, the British retreat to New York.

June 29, 1776

General William Howe, and his brother, Admiral Richard Howe, arrive in New York harbor from Boston. In late June, the American army from the campaign against Montreal and Quebec reassembles at Fort Ticonderoga.

July 9, 1776

Washington leads an American Independence celebration in New York City, reading the Declaration of Independence to the troops and sending copies of it to generals in the Continental Army. George Washington to General Artemas Ward, July 9, 1776

July 14, 1776

The Howe brothers attempt to contact Washington to open negotiations, but Washington refuses their letter which is addressed to "George Washington, Esq., etc., etc.," a form of address appropriate for a private gentleman rather than for the commander of an army.

August 20, 1776

British forces, concentrated on Staten Island, cross over to Long Island for the war's first major battle. Washington has approximately 23,000 troops, mostly militia. Commanding Continental officers participating are Lord Stirling (William Alexander), Israel Putnam, John Sullivan, and Nathanael Greene. Howe has approximately 20,000 troops.

August 27, 1776

Howe attacks on Long Island and the American lines retreat. Lord Stirling holds out the longest before surrendering the same day. Robert H. Harrison, one of Washington's aides, writes Congress with news of the day's battle and information on Washington's current whereabouts on Long Island. Robert H. Harrison to Congress, August 27, 1776

August 28-29, 1776

During a heavy night fog, Washington and his army silently evacuate Long Island by boat to Manhattan, escaping almost certain capture by Howe's army.

August 31, 1776

Washington writes Congress about the evacuation and about a forthcoming request from British General William Howe to meet with members of Congress. A formal request from Howe is sent to Congress via captured American general, John Sullivan. A committee made up of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge meet with Howe on September 6. But discussions cease when the committee learns that Howe's only offer is that if the rebels lay down their arms, they may await the generosity of the British government. George Washington to Congress, August 31, 1776

September 15, 1776

Howe's army attacks Manhattan at Kip's Bay, where a Connecticut militia unit flees in fear and confusion. Washington writes Congress, calling the rout "disgraceful and dastardly conduct," and describing his own efforts to halt it. On September 16, the same unit redeems itself in the battle of Harlem Heights. In his September 17 general orders, Washington praises the officers and soldiers, noting the contrast to the "Behavior of Yesterday." George Washington to Congress, September 16, 1776 | George Washington, General Orders, September 17, 1776

September 24, 1776

Washington writes Congress on the obstacles to creating a permanent, well-trained Continental Army to face the regulars of the British Army and describes his frustrations in employing local militia units. He closes by acknowledging the traditional fears of a "standing army" in a republic but urges Congress to consider that the war may be lost without one. George Washington to Congress, September 24, 1776

September 26, 1776

Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Thomas Jefferson are named American commissioners to France by Congress.

October 11-13, 1776

Benedict Arnold wins the naval battle of Valcour Island off Crown Point. A small victory, it nonetheless causes Sir Guy Carleton to delay plans for an invasion from Canada.

October 16, 1776

Washington orders the retreat of the army off Manhattan Island. New York City is lost to the British. British General William Howe wins a knighthood for his successes in the campaign of 1776.

November 16, 1776

Fort Washington and its garrison of 250 men on the east side of the Hudson River fall to the British, commanded by General Charles Cornwallis. Fort Lee, on the west side, is abandoned by the Americans two days later.

November - December 1776

Under command of General Charles Cornwallis, the British invade New Jersey. Cornwallis takes Newark November 28 and pursues Washington and his army to New Brunswick.

December 6, 1776

British General Henry Clinton takes Newport, Rhode Island.

December 7, 1776

Washington's army finishes crossing the Delaware, with the British close behind. Once on the western side of the river, Washington awaits reinforcements. By mid-December, he is joined by Horatio Gates, John Sullivan, and their Continental Army forces. The British establish winter camps in various New Jersey locations , with the Hessians primarily at Bordentown and Trenton, and the British regulars at Princeton.

December 25, 1776

Washington orders readings to the assembled troops from Thomas Paine's The Crisis , with its famous passage, "These are the times that try men's souls." The Crisis had just been published December 23 in Philadelphia.

December 25-26, 1776

During the night, General Washington, General Henry Knox, and troops cross the Delaware in freezing winter weather to launch a surprise attack on British and Hessian mercenaries encamped at Trenton. Early morning, December 26, the attack begins, with Generals Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan leading the infantry assault against the Hessians, commanded by Colonel Johann Rall. After a short battle, Washington's army takes Trenton.

December 27, 1776

Congress gives Washington special powers for six months. He may raise troops and supplies from states directly, appoint officers and administer the army, and arrest inhabitants who refuse to accept Continental currency as payment or otherwise show themselves to be disloyal. Washington acknowledges these extraordinary powers, assuring Congress that he will use them to its honor. George Washington to Congress, January 1, 1777

December 31, 1776

Washington writes Congress with a general report of the state of the troops. Toward the end, he notes that "free Negroes who have served in the Army, are very much dissatisfied at being discarded." To prevent them from serving the British instead, he has decided to re-enlist them. In 1775, Washington had opposed enlisting not just slaves but free blacks as well. His general orders of November 12, 1775, direct that "neither Negroes, Boys unable to bare Arms, nor old men unfit to endure the fatigues of the campaign" are to be recruited. In 1776 and thereafter, he reverses himself on both counts. George Washington, General Orders, November 12, 1775 | George Washington to Congress, December 31, 1775

January 3, 1777

Washington's army captures the British garrison at nearby Princeton. Washington sets up winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, where he spends the next several months rebuilding the Continental Army with new enlistments.

April 12, 1777

British General Charles Cornwallis opens the 1777 campaign in New Jersey in an attempt to lure Washington and his army out from winter headquarters at Morristown.

April 17, 1777

Washington writes General William Maxwell, commander of the Continental light infantry and also of the New Jersey militia, to ready himself and his troops for the 1777 campaign. George Washington to William Maxwell, April 17, 1777

May 29, 1777

Washington moves his headquarters to Middlebrook, south of Morristown.

June 20, 1777

Washington writes Congress and General Philip Schuyler on the success of the New Jersey militia in forcing the British out of New Jersey and on the general failure of the British to win the inhabitants there back to allegiance to the Crown. George Washington to Congress, June 20, 1777 | George Washington to Philip Schuyler, June 20, 1777

June 22, 1777

The British evacuate New Brunswick, New Jersey, to Amboy, and then back to Staten Island.

June 27, 1777

The Marquis de Lafayette arrives in Philadelphia from France to offer his services to the American cause. He is nineteen years old. He is commissioned a major general by Congress and meets Washington on August 1. He and Washington form a close friendship.

Washington moves his army to the Hudson above the Highlands of New York. The Highlands are a range of hills across the Hudson Valley. American forts built on each side of the Hudson River, a giant thirty-five-ton, 850-link chain, and a series of spiked logs on the river bottom all guard access to the interior of the country.

July 11, 1777

Washington writes Congress requesting that it order Benedict Arnold to join Philip Schuyler in halting British General John Burgoyne's invasion of New York from Canada, which began on June 23.

July 23, 1777

General Sir William Howe sets sail from New York City with approximately 15,000 men. He embarks on a campaign to take Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress. General Henry Clinton remains in command in New York City with British and loyalist forces. Howe and his force land at Head of Elk on Chesapeake Bay August 25.

August 3, 1777

British Colonel Barry St. Leger with a force of British regulars, Canadians, and Indian allies, lays siege to Fort Stanwix (Schuyler) in the western Mohawk Valley. Benedict Arnold and 900 Continentals arrive, forcing St. Leger to retreat back to Canada.

August 6, 1777

The Battle of Oriskany, British Colonel Barry St. Leger and Seneca Indians and loyalists ambush patriot German militia and Oneida Indian allies under command of General Nicholas Herkimer. The hand-to-hand fighting is so severe that St. Leger's Indian allies abandon him in disgust. Herkimer dies of his wounds. The battle brings to a head a long-impending civil war among the nations of the Iroquois League.

August 16, 1777

In the Battle of Bennington, where Burgoyne has sent a detachment to forage for much needed supplies, the American Brigadier General John Stark and local militia kill or capture nearly 1,000 of Burgoyne's 7,000 troop invading army, further slowing British invasion plans.

September 11, 1777

In the Battle of Brandywine, Howe and Washington clash, with major engagements near Birmingham Meeting House Hill. Washington is forced to retreat.

September 19-21, 1777

Washington's army is camped about twenty miles from Germantown, where Howe is concentrated for his invasion of Philadelphia. The British inflict 1000 casualties in a night attack on General Anthony Wayne's Brigade near Paoli's Tavern. The attack on Wayne is led by British General Charles Grey, called "No Flint" Grey because of his preference for the bayonet over the musket. The "Paoli Massacre" becomes an American rallying cry among Continental troops. Wayne requests a court martial to clear his name of any dishonor, a not unusual request. Washington's general orders of November 1, 1777, report the court's favorable decision. George Washington, General Orders, November 1, 1777

October 3, 1777

At 7pm in the evening, Washington's forces begin the march to Germantown, where Washington hopes to encircle Howe's army. Commanding 8,000 Continentals and 3,000 militia are Generals Adam Stephen, Nathanael Greene, Alexander McDougall, John Sullivan, Anthony Wayne, and Thomas Conway. George Washington, General Orders, October 3, 1777

October 4, 1777

Washington's forces are defeated at Germantown. One wing marches down the wrong road, and General Conway's brigade inadvertently alerts the British to the impending attack. In the course of battle, Wayne and Stephen's men fire upon each other in confusion. Greene's retreat is mistakenly taken by the rest of the troops as a signal for a general retreat. Washington writes Congress an account of the battle, attempting to allay Congress's and his own disappointment by describing it as "rather unfortunate than injurious" in the large scale of things. George Washington to Congress, October 5, 1777

October 6, 1777

Washington responds to a letter from British General William Howe, who has written about the destruction of mills belonging to "peaceable Inhabitants" during the recent engagement. Howe allows that Washington probably did not order these depredations but requests that he put a stop to them. Washington responds heatedly, citing depredations by the British in Charles Town, Massachusetts, which was burned at the beginning of the war, and of other instances. In a short additional letter of the same date, Washington writes Howe that his pet dog has fallen into American hands and he is returning him. Washington and Howe correspond regularly in the course of the War, most often about prisoner exchanges. George Washington to William Howe, October 6, 1777 | George Washington to William Howe, October 6, 1777

October 17, 1777

British General John Burgoyne surrenders at Saratoga, to General Horatio Gates, the new commander of the northern army. The "Convention of Saratoga," negotiated by Gates, allows Burgoyne's army of 5,871 British regulars and German mercenaries to return to England and Europe on the promise that they will not fight in North America again. Congress finds various reasons for not allowing Burgoyne's army to leave, for fear that its return to England or the Continent will free an equal number of other troops to come to North America to fight. Burgoyne's army will be detained in various locations in Massachusetts and then settled on a tract of land in Virginia near Charlottesville. In September 1781, the "Convention Army" is removed to Maryland because of Cornwallis's invasion of Virginia. At the close of the War, Burgoyne's army has dwindled to a mere 1,500 due to escapes, desertions, but most significantly to the number of the troops deciding to stay and settle in America.

October 19, 1777

Howe and the British enter Philadelphia. Congress has fled to York, Pennsylvania.

September 24 - October 23, 1777

British general henry clinton's invasion of the highlands, september 24.

General Henry Clinton in New York receives substantial reinforcements of British regulars and German mercenaries.

Clinton receives a note from General John Burgoyne who warns him about Horatio Gates's army, which is growing with additions of militia.

Clinton and his forces attack and take Fort Montgomery and make a bayonet attack on Fort Clinton. Both forts are on the west side of the Hudson River. The Highlands region is commanded by Israel Putnam, a Continental major general. The forts are commanded by newly elected governor of New York, George Clinton, and his brother, James, both of whom are distant cousins of British General Henry Clinton. George and James Clinton and most of the forts' defenders manage to escape.

American troops burn Fort Constitution on the east side of the Hudson River and depart. George Clinton and Israel Putnam decide to retreat north with the remnant of their troops. British Major General John Vaughn, Commodore Sir James Wallace, and former royal governor of New York, William Tryon, and their forces continue up the Hudson River. October 14, they burn the shipyards of Poughkeepsie, and a number of small villages and large houses, among the latter that of William Livingston, governor of New Jersey.

The British force which began its invasion up the Hudson River reaches Albany. There, Major General John Vaughn learns of Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga the previous day.

British forces under Major General Vaughn begin their return back down the Hudson River to New York City, and in early November they evacuate the Highlands and the forts they have captured there.

November 3, 1777

The "conway cabal" and valley forge.

General Lord Stirling (William Alexander) of New Jersey writes Washington, enclosing a note that recounts General Thomas Conway's criticisms of Washington and of Conway's preference for Horatio Gates as commander in chief of the Continental Army. October 28, Gates's aide, James Wilkinson, had incautiously related the matter over drink in a tavern in Reading, where Stirling was also staying. Washington writes Conway, November 5, tersely informing him of his knowledge of the affair. George Washington to Thomas Conway, November 5, 1777

In the wake of his victory over Burgoyne, Horatio Gates, the "Hero of Saratoga," has been appointed by Congress as the head of a reorganized Board of War. Thomas Conway is appointed Inspector General of the Army. December 13, Conway visits Washington and his troops at winter quarters at Valley Forge. There the troops have been suffering severe hardships and to some critics they no longer resemble an organized army. After exchanges between Conway and Congress, and Washington and Congress, the Board's Congressional members decide to visit Valley Forge. Carrying out a thorough investigation, the Board places blame on Congress and Thomas Mifflin, quartermaster general, for the low condition of the Army at Valley Forge. Washington writes Lafayette December 31, 1777, and Patrick Henry, February 19 and March 28, 1778. Washington describes the conditions at Valley Forge as at times "little less than a famine." George Washington to Lafayette, December 31, 1777 | George Washington to Patrick Henry, February 19, 1778 | George Washington to Patrick Henry, March 28, 1778

January 2, 1778

Washington forwards to governor Nicholas Cooke a letter from General James Varnum advising him that Rhode Island's troop quota should be completed with blacks. Washington urges Cooke to give the recruiting officers every assistance. In February, the Rhode Island legislature approves the action. Enlisted slaves will receive their freedom in return for their service. The resulting black regiment, commanded by white Quaker Christopher Greene, has its first engagement at the battle of Rhode Island (or, Newport) July 29-August 31, where it holds off two Hessian regiments. The regiment also fights at the battle of Yorktown. Slaves enlisted in the Continental Army typically receive a subsistence, their freedom, and a cash payment at the end of the war. Slaves and free blacks rarely receive regular pay or land bounties. In 1777, the New Jersey militia act allows for the recruitment of free blacks but not slaves, as does Maryland's legislature in 1781. On March 20, 1781, New York authorizes the enlistment of slaves in militia units, for which they receive their freedom at the end of the war. Virginia rejects James Madison's arguments for enlisting slaves in addition to free blacks, but many enlist anyway, presenting themselves for freedom after the war. George Washington to Nicholas Cooke, January 2, 1778

February 6, 1778

The Franco-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce is signed in Paris. Since 1776, the French government has been secretly providing Congress with military supplies and financial aid. March 13, the French minister in London informs King George III that France recognizes the United States. May 4, Congress ratifies the Treaty of Alliance with France, and further military and financial assistance follows. By June, France and England are at war. The American Revolution has become an international war.

February 18, 1778

Washington addresses a letter to the inhabitants of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, requesting cattle for the army for the period of May through June. Washington writes them that the "States have contended, not unsuccessfully, with one of the most Powerful Kingdoms upon Earth." After several years of war, "we now find ourselves at least upon a level with our opponents." George Washington to the Inhabitants of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, February 18, 1778

February 23, 1778

Baron Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Steuben, a volunteer from Germany, arrives at Valley Forge with a letter of introduction from the President of Congress, Henry Laurens. Congress publishes his military training manual, which he has had translated into English. He trains a model company of forty-seven men at Valley Forge and then proceeds to the general training of the army. Congress commissions Steuben a major general and makes him an inspector general of the Continental Army. Steuben becomes an American citizen after the war.

March 1, 1778

Congress orders the Board of War to recruit Indians into the Continental Army. March 13, Washington writes the Commissioners of Indian Affairs on how he thinks he may employ the Indians recruited. George Washington to Philip Schuyler, James Duane, and Volkert Douw, March 13, 1778

March 8, 1778

Lord Germain (George Sackville), Colonial Secretary in London, sends British General Henry Clinton orders for a change of direction in the conduct of the war. The British are to focus on the south, where Germain estimates loyalists to be more numerous. Actions in the north are to be limited to raids and blockades of the coast. May 8, Clinton will replace General Sir William Howe as commander of British forces in North America.

The British government sends the Carlisle Commission to North America. The Commission is made up of the Earl of Carlisle (Frederick Howard), William Eden, and George Johnston, and their secretary. Parliament has repealed all laws opposed by the American colonies since 1763. The Commission is instructed to offer home rule to the Colonies and hopes to begin negotiations before Congress receives news of the Franco-American Treaty (which it does on May 8). Congress ratifies the Treaty and ignores the Commission. April 22, Congress resolves not to engage in negotiations on terms that fall short of complete independence. Late in 1778, the Commission returns to England.

May-June 1778

British General Henry Clinton begins to move the main part of the British army from Pennsylvania to New York via New Jersey. Washington's army, also located in Pennsylvania, gives chase.

June 18, 1778

Washington sends six brigades ahead and on June 21 he crosses the Delaware River with the rest of the army. By June 22, the British are in New Jersey, and Benedict Arnold is fast approaching the twelve-mile long baggage train that makes up the end of Clinton's marching army.

June 28, 1778

The Battle of Monmouth Courthouse. Washington's army catches up with Clinton's. The one-day battle is fought to a stalemate, both armies exhausted by the day's unusual heat. But Washington is impressed with the performance of the American troops against the well-trained veteran British regulars. Clinton and his army continue on to New York, while Washington establishes camp at White Plains.

June 29, 1778

Washington writes in his general orders of the day about the success of the New Jersey militia in "harrassing and impeding their [the British] Motions so as to allow the Continental Troops time to come up with them" before the battle of Monmouth Courthouse. German Captain John Ewald, fighting for the British, in his Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal (New Haven and London, 1979), observes during the march through New Jersey that the "whole province was in arms, following us with Washington's army, constantly surrounding us on our marches and besieging our camps." "Each step," Ewald writes, "cost human blood." From now on, Washington begins to employ local militia units in this manner more often.

July 3, 1778

Loyalist Colonel John Butler with local troops and Seneca Indian allies invades Wyoming Valley, north of the Susquehanna River, and attacks at "Forty Fort." In the frontier war along the New York and Pennsylvania frontier, Onandagas, Cayugas, Senecas, and Mohawks of the Iroquois League ally with the British. Joseph Brant (Joseph Fayadanega), a Mohawk war chief educated in English missionary schools and an Anglican convert, has significant influence among British government and military leaders. Oneidas and Tuscororas ally with the Americans. Washington writes Philip Schuyler, a member of the Indian commission for the northern department. George Washington to Philip Schuyler, July 22, 1778

July 4, 1778

George Rogers Clark defeats the British and captures Kaskaskia near the Mississippi River. Clark has been organizing the defense of the sparsely settled Kentucky region against British and Indian ally raids. In October 1777, Clark puts before Virginia governor Patrick Henry a plan to capture several British posts in the Illinois country, of which Kaskaskia is one. Clark and about 175 men take the fort and town, which is inhabited mainly by French settlers. Clark convinces them and their Indian allies on the Wabash River to support the American cause. The British continue to hold sway at Fort Detroit, commanded by Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, and Clark spends the next several years attempting to dislodge him. Washington writes governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, December 28, 1780, in support of Clark's efforts to take Fort Detroit. George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, December 28, 1780

July - August 1778

Charles Hector, Comte d'Estaing and his French fleet plan to participate with General John Sullivan in a combined assault on the British position in Newport, Rhode Island. Sullivan's troops are delayed and d'Estaing's fleet is battered by a hurricane after an indecisive battle. He withdraws to Boston and later sails for the Caribbean Islands where he attacks British islands.

November 9, 1778

British General Henry Clinton sends approximately 3,000 troops south under Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, and a fleet under command of Admiral Hyde Parker is assembled to coordinate an invasion of South Carolina and Georgia with General Augustine Prevost and his regular and loyalist troops in Florida. Campbell and his troops land at Savannah in late December.

November 14, 1778

Washington writes Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress, confidentially, about a plan for a French campaign against the British in Canada that Lafayette very much wants to lead. In 1759, during the Seven Years War, the French had been driven out of Canada by the British and American colonial forces. Washington has become personally attached to the young Lafayette. But he is also aware of the eagerness of all the French officers serving with the American cause to regain Canadian territories. Washington expresses concerns about the future independence of the American republic should European powers retain a strong presence in North America: a French presence able to "dispute" the sea power of Great Britain, and Spain "certainly superior, possessed of New Orleans, on our Right." George Washington to Henry Laurens, November 14, 1778

November 1778

Washington detaches General Lachlan McIntosh from Valley Forge to command the western department of the Ohio country where bitter frontier war has erupted. McIntosh establishes Fort McIntosh on the Ohio River, 30 miles from Pittsburgh, and Fort Laurens, further west, as bases from which to launch campaigns against British and Shawnee, Wyandot, and Mingo allies operating out of Fort Detroit. After bitter warfare, McIntosh is forced to abandon the forts in June of 1779.

January 29, 1779

Augusta, the capital of Georgia, falls to British forces. General Benjamin Lincoln, whose army is camped at Purysburg, South Carolina, sends a detachment toward Augusta and on February 13, the British evacuate the town.

February 25, 1779

Congress directs Washington to respond to British, Indian, and loyalist attacks on frontier settlements in New York and Pennsylvania. Washington sends out an expedition under command of General John Sullivan. Sullivan's forces include William Maxwell and a New Jersey brigade, Enoch Poor and a New Hampshire brigade, and Edward Hand and Pennsylvania and Maryland troops. After a series of savage raids and counter-raids between the British and the Americans, including an encounter with British Indian ally Joseph Brant and his Mohawks, and Captain Walter Butler (John Butler's son) and his loyalists, the expedition returns home on September 14. Forty Iroquois villages and their extensive farms lands and crops have been destroyed. The Iroquois soon return, resettle, and rejoin the British in an retaliatory invasion in the northwest. George Washington to John Sullivan, March 6, 1779

March 3, 1779

British Major James Mark Prevost defeats Brigadier General John Ashe and his force at Briar Creek, Georgia. In response, Benjamin Lincoln and the southern army cross into Georgia. Lincoln's and Prevost's forces move back and forth between Georgia and South Carolina in an attempt to engage each other, but eventually summer heat and illness bring both armies to a standstill.

March 20, 1779

Washington responds to Henry Laurens's March 16th letter on the possibility of raising a black regiment for the defense of the south. Washington writes Laurens that he would rather wait till the British first raise such regiments before the Americans do so. He also expresses some general reservations. But "this is a subject that has never employed much of my thoughts," and he describes his opinions as "no more than the first crude Ideas that have struck me upon the occasion." Henry Laurens is from South Carolina. Previously president of Congress, he is serving on a committee charged with forming a plan of defense for the south. The committee issues its report March 29, urging the formation of regiments of slaves for the defense of the south, for which Congress will compensate slaveowners and the slaves will receive their freedom and $50. Henry Laurens's son, John Laurens is appointed to raise the regiments. South Carolina and Georgia reject Congress's recommendation (see entry under July 10, 1782 below). Successive commanders of the southern army, Benjamin Lincoln and Nathanael Greene, support the formation of slave regiments in the south but to no avail. George Washington to Henry Laurens and Thomas Burke, March 18, 1779 | George Washington to Henry Laurens, March 20, 1779

May 28, 1779

British General Henry Clinton launches another campaign up the Hudson River. On May 30, New York Governor George Clinton orders out the militia. June 1, the British take Stony Point and Verplank's Point on either side of the river.

June 21, 1779

Spain declares war on Great Britain.

June 30, 1779

William Tryon, former royal governor of New York, and 2,600 loyalists and British regulars on forty-eight ships raid Fairport, New Haven, and Norwalk, Connecticut. Tryon wants to prosecute a war of desolation against rebel inhabitants. On July 9, he orders most of Fairfield burned because its militia shot at the British from within their houses, and on July 11 he burns Norwalk. British General Henry Clinton, probably reluctant to endorse Tryon's theories of warfare, never gives him an independent command again.

July 16, 1779

Anthony Wayne and his force of light infantry force the British out of Stony Point, and August 18-19 Major Henry Lee takes the British post at Paulus Hook. Neither of these positions are maintained after their capture, but they are morale boosters in a war that has become a stalemate.

September 27, 1779

Washington writes state governors Jonathan Trumbull (Connecticut), George Clinton (New York), and William Livingston (New Jersey) about reports of the arrival of a French Fleet and of the necessity of preparing the militia and raising food supplies, especially flour. George Washington, Circular Letter, September 27, 1779

October 4, 1779