Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

115 Waste Management Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Waste management is a crucial issue in today's world, as the amount of waste produced continues to grow at an alarming rate. From household trash to industrial waste, finding sustainable solutions for managing and reducing waste is essential for protecting the environment and public health.

If you're tasked with writing an essay on waste management, you may be struggling to come up with a topic that is both interesting and relevant. To help you get started, here are 115 waste management essay topic ideas and examples that you can use as inspiration for your own writing:

- The importance of proper waste management in protecting the environment

- The impact of waste management on public health

- Strategies for reducing household waste

- The role of recycling in waste management

- The benefits of composting for waste reduction

- The challenges of managing electronic waste

- The environmental impact of plastic waste

- The economic benefits of sustainable waste management practices

- The ethical implications of waste disposal methods

- The role of government in regulating waste management

- The impact of waste management on climate change

- The potential for waste-to-energy technologies to reduce landfill waste

- The importance of educating the public about waste management

- The role of businesses in implementing sustainable waste management practices

- The social justice implications of waste management

- The impact of waste management on wildlife and ecosystems

- The benefits of using biodegradable materials to reduce waste

- The challenges of managing construction and demolition waste

- The potential for using waste as a resource in circular economy models

- The role of technology in improving waste management processes

- The impact of food waste on global hunger and food security

- The benefits of implementing zero-waste initiatives in communities

- The role of NGOs in promoting sustainable waste management practices

- The potential for using drones to monitor and manage waste

- The impact of waste management on water quality

- The benefits of community-based waste management programs

- The challenges of managing hazardous waste

- The potential for using blockchain technology to track waste disposal

- The role of education in promoting sustainable waste management practices

- The impact of waste management on air quality

- The benefits of waste segregation and sorting programs

- The challenges of managing medical waste

- The potential for using robots to automate waste sorting processes

- The role of public-private partnerships in improving waste management

- The impact of waste management on urban planning and development

- The benefits of using anaerobic digestion to process organic waste

- The challenges of managing electronic waste in developing countries

- The potential for using machine learning algorithms to optimize waste collection routes

- The role of social media in raising awareness about waste management issues

- The impact of waste management on biodiversity conservation

- The benefits of implementing extended producer responsibility programs

- The challenges of managing marine litter

- The potential for using satellite imagery to monitor illegal waste dumping

- The role of indigenous communities in sustainable waste management practices

- The impact of waste management on land degradation

- The benefits of using biochar to improve soil quality

- The challenges of managing radioactive waste

- The potential for using 3D printing to create products from recycled materials

- The role of artists in raising awareness about waste management issues

- The impact of waste management on social inequality

- The benefits of implementing pay-as-you-throw waste pricing schemes

- The challenges of managing agricultural waste

- The potential for using blockchain technology to create a transparent waste management system

- The role of citizen science in monitoring waste pollution

- The impact of waste management on tourism

- The benefits of using drones to collect and transport waste

- The challenges of managing industrial waste

- The potential for using gene editing technologies to break down plastic waste

- The role of policymakers in promoting sustainable waste management practices

- The impact of waste management on public perception of cities

- The benefits of using algae to clean up wastewater

- The challenges of managing construction and demolition waste in urban areas

- The potential for using artificial intelligence to optimize waste management processes

- The role of community gardens in reducing food waste

- The impact of waste management on mental health

- The benefits of using green roofs to reduce stormwater runoff

- The challenges of managing asbestos waste

- The potential for using drones to monitor landfill sites

- The role of youth groups in promoting waste management education

- The impact of waste management on renewable energy production

- The benefits of implementing waste audits in businesses

- The challenges of managing wastewater treatment sludge

- The potential for using geospatial technologies to map waste hotspots

- The role of religious organizations in promoting waste reduction

- The impact of waste management on indigenous rights

- The benefits of using blockchain technology to create a circular economy

- The challenges of managing pharmaceutical waste

- The potential for using robots to clean up ocean plastic pollution

- The role of community activists in advocating for waste management reform

- The impact of waste management on green jobs creation

- The benefits of using drones to monitor illegal waste dumping

- The challenges of managing construction and demolition waste in rural areas

- The potential for using satellite imagery to track waste flows

- The role of citizen science in monitoring air quality near waste facilities

- The impact of waste management on water scarcity

- The benefits of using biopesticides to control pests in waste management facilities

- The challenges of managing medical waste in conflict zones

- The potential for using machine learning algorithms to predict waste generation patterns

- The role of grassroots organizations in promoting waste reduction

- The impact of waste management on mental well-being

- The benefits of using drones to monitor illegal waste dumping in remote areas

- The challenges of managing electronic waste in rural communities

- The potential for using blockchain technology to create a decentralized waste management system

- The role of community gardens in promoting sustainable waste management practices

- The impact of waste management on social cohesion

- The benefits of using drones to monitor waste collection routes

- The challenges of managing hazardous waste in developing countries

- The potential for using machine learning algorithms to optimize waste sorting processes

- The role of social entrepreneurs in developing innovative waste management solutions

- The benefits of using blockchain technology to create a transparent waste management system

These waste management essay topic ideas and examples cover a wide range of issues and perspectives, giving you plenty of options to explore in your writing. Whether you're interested in the environmental, social, economic, or technological aspects of waste management, there's sure to be a topic that piques your interest. Good luck with your essay, and happy writing!

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Journal Proposal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Waste management, waste indicators and the relationship with sustainable development goals (sdgs): a systematic literature review.

Share and Cite

Ram, M.; Bracci, E. Waste Management, Waste Indicators and the Relationship with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024 , 16 , 8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198486

Ram M, Bracci E. Waste Management, Waste Indicators and the Relationship with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability . 2024; 16(19):8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198486

Ram, Meetha, and Enrico Bracci. 2024. "Waste Management, Waste Indicators and the Relationship with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 16, no. 19: 8486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198486

Article Metrics

Further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- How it works

Useful Links

How much will your dissertation cost?

Have an expert academic write your dissertation paper!

Dissertation Services

Get unlimited topic ideas and a dissertation plan for just £45.00

Order topics and plan

Get 1 free topic in your area of study with aim and justification

Yes I want the free topic

Waste Management Dissertation Topic Ideas

Published by Owen Ingram at January 2nd, 2023 , Revised On August 11, 2023

Choosing an ideal waste management dissertation topic can be challenging. In order to ensure a healthy environment, we must learn to manage waste in a responsible manner. Contribute to the body of knowledge in the field, capture the reader’s attention in an important area that is usually overlooked, and maintain an academic tone by choosing a relevant and unique waste management thesis topic from the list below.

For you to avoid the headache and have a pleasant dissertation writing experience, our subject matter experts have compiled a free list of the top custom waste management dissertation topic ideas.

You can quickly select one that appeals to you and conduct your research on it by reviewing the following list of possible waste management dissertation topics:

List of Waste Management Dissertation Ideas

- Investigating how decision-making affects waste management optimization.

- Determining the elements that might reduce risk in situations involving the handling of hazardous waste.

- An examination of the impact of environmental legislation on garbage from building

- Identifying the potential environmental risks associated with solid waste management and greenhouse emissions.

- An original investigation of the influence of gender on attitudes and perceptions of trash management in the UK.

- Should we mine landfills for their valuable metals as part of the waste-to-resources process? Weighing the risks and the profits

- Examine the population’s compliance with trash management in urban vs Rural parts of the UK.

- A study of the significance of managing nuclear waste.

- An evaluation of the impact of industrial waste metals in the UK on agricultural output and soil fertility and the harmful consequences of these items on consumers’ health.

- Impact of oil spills on coastal waters: a comprehensive analysis. A thorough examination of each oil leak incident between 2000 and 2020, including an environmental impact assessment.

- High-level versus low-level radioactivity wastes are compared regarding safety regulations for managing radioactive waste.

- An innovative study on recycling garbage into usable, ecological building materials. How will it affect the UK’s building industry, and is it practical?

- A comparison of textile waste from pre- and post-consumer sources.

- Focus on developing nations for the effects of toxic animal manure on human health and the environment.

- An investigation into the UK’s regulations for treating industrial wastewater from companies near rivers, lakes, and the sea.

- A comparison and analysis of the ongoing argument between waste minimization and waste management. Weighing the benefits and drawbacks.

- Economic benefits of better treatment plant construction for sustainable solid waste management.

- Implementation and policy of solid waste management in emerging and rich economies are compared.

- Waste management techniques in the fashion industry: possible difficulties and necessary solutions.

- How virtual and visual aids can be used to teach waste management at the university level?

- Focusing on X countries, local government involvement in municipal solid waste management policy.

- Comparative examination of e-waste management practices in the world’s poorer nations.

- Descriptive research looks into waste management methods’ effects on human health.

- Using a descriptive method, we investigate polymer waste’s biodegradation, incineration, and recycling.

- Creation of a hypothetical waste management strategy for a project in a developing nation during construction.

For your convenience, our senior industry professionals have also compiled a list of fantastic waste management dissertation topic ideas that you can use to create your own topic. However, if you still need further help in dissertation writing, our expert writers are available to help you out.

Free Dissertation Topic

Phone Number

Academic Level Select Academic Level Undergraduate Graduate PHD

Academic Subject

Area of Research

Frequently Asked Questions

How to find waste management dissertation topics.

To find Waste Management dissertation topics:

- Research recent waste challenges.

- Investigate environmental policies.

- Explore recycling innovations.

- Examine waste reduction strategies.

- Consider economic implications.

- Select a specific aspect that intrigues you for an impactful topic.

You May Also Like

Need interesting and manageable Environmental Engineering dissertation topics? Here are the trending Environmental Engineering dissertation titles so you can choose the most suitable one.

Japanese Studies is an interdisciplinary academic field focusing on Japan’s language, history, culture, and society. It is an invaluable resource for researchers who seek to gain a comprehensive understanding of the country’s past and present.

A nurse who specializes in adult nursing assists the elderly with eating, bathing, dressing, and other daily tasks. It requires compassion, patience, excellent communication skills, and physical strength to succeed in this career.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Circularity in waste management: a research proposal to achieve the 2030 Agenda

- Operations Management Research 16(3)

- King Juan Carlos University

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- WASTE MANAGE RES

- Nadiah Abdul Mulok Oon

- PROCESS SAF ENVIRON

- Selvam D Christopher

- Thandavamoorthy Raja

- Ravikumar Jayabal

- Louis Freboeuf

- Sajad H. Wani

- J ENVIRON MANAGE

- Dongchen Han

- Mohsen Kalantari

- Abbas Rajabifard

- Kunle Ibukun Olatayo

- Paul T. Mativenga

- ENVIRON SCI POLLUT R

- Genoveva Rosano-Ortega

- Domingo Ribeiro Soriano

- Damini Sundar

- K. Mathiyazhagan

- CIRP ANN-MANUF TECHN

- ENERG POLICY

- Kirty Majumdar

- Balkrishna E. Narkhede

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Office of the Provost

- Meet the Provost

- Schools and Colleges

- BFSI Bioblend Tree-Free Paper

- Cargill Anova Asphalt Solutions

- DoD Sustainable Products Demonstration, Evaluation & Implementation Program and the Sustainable Products Center

- Klondike Gold Rush National Park

- Profiles on Biobased Success

- UCLA's Biobased Astroturf Intramural Field

- Biobased Study Questions

- BioPreferred Program

- Kennedy Space Center

- City of Atlanta

- GSA EV Pilot Program Inspires Innovation at Air Force, EPA, and VA

- Kiev’s Electric Taxis Bolster National Security

- United Parcel Service

- Fleet Electrification Study Questions

- Additional Fleet Resources

- Key Government Organizations Supporting Fleet Electrification

- What is an Electric Vehicle?

- The National Park Service

- Department of the Navy: Mesquite 3 Solar PPA

- Capital Partners Solar Project

- City of Sacramento Solar PPA

- General Services Administration Tribal PPA

- Hewlett Packard 112 MW PPA

- Power Purchase Agreement Study Questions

- Additional Financial Incentives

- Federal Agency PPA Project Assistance

- Historical Overview of the PPA

- PPA NEPA Requirements

- Power Purchase Agreement Basics

- Renewable Energy Certificates Overview

- General Services Administration

- CDP Supply Chain Program

- Ford Beyond Four Walls

- Additional Supply Chain Resources

- EPA's Recommendations of Specifications, Standards and Ecolabels

- Federal Acquisition Regulations

- United States Postal Service

- General Motors Redefines Waste

- Memphis VAMC Tracks Progress

- The Smithsonian Institution

- Additional Resources

- Army Net-Zero Waste

- E.O. 13693 Waste Requirements

- Waste Study Quesions

- Diversity Program Review Team

- Core Indicators

- Course Audit Program

- Faculty Governance

- Librarians Governance

- Policies, Procedures, and Guidelines

- Academic Honors

- Faculty Honors

- Honorary Degrees

Waste Management Study Questions

Mastering the basics:.

- How do the three categories of municipal solid waste (compost, recycling and landfill) differ?

- Why are landfills environmentally harmful?

- What are the current executive orders on waste management?

- What are common barriers to implementing waste diversion programs?

- What are the benefits of maximizing waste diversion?

- What waste management services does your locality provide?

Especially for Federal managers:

- What federal agencies are you consulting with for technical advice and oversight?

- Have you conducted a cost-benefit analysis?

- How does a waste management program fit into your budget?

- Where can you find tools, templates and other contract examples for your program’s needs?

- What method of training, for current employees and during staff turnover, makes the most sense for your agency?

- Who are your receiving compactor facilities, and what are their conditions of service?

- What is the most accurate and efficient method for conducting audits on collected waste?

- Does your agency have the capacity to sort waste before it is picked up?

- How frequently should the waste hauler be scheduled to pick up?

- Do you have the capacity to store waste prior to pick-up, and what will be your limit on this holding period?

- What is your waste receiving facility’s level of tolerance for contamination?

- How will your agency minimize contamination by visitors and employees?

- What are the appropriate locations for receptacles throughout your working environment?

- Do you need receptacles for hazardous waste?

- How can you secure the management of safe and sanitary receptacles throughout your work environment?

- Where will employees have the opportunity to submit questions and concerns regarding waste management, and how will you effectively address this input?

- How will you meet your standards for waste diversion during public/private events?

- How will you use assessments to monitor and adapt your waste management program?

What would you do if…

...your receiving facility reports that your waste is too contaminated?

...you are receiving complaints regarding waste receptacles?

...subsequent to piloting the program, you find that costs are outweighing returns and cannot be justified?

...you continue to fall short of the threshold for waste diversion?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier Sponsored Documents

The wicked problem of waste management: An attention-based analysis of stakeholder behaviours

Giuseppe salvia.

a The Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment, University College London, 14 Upper Woburn Place, WC1H 0NN, London, UK

Nici Zimmermann

Catherine willan.

b UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources. Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, WC1H 0NN, London, UK

Joanna Hale

c UCL Centre for Behaviour Change, 1-19 Torrington Place, WC1E 7HB, London, UK

Hellen Gitau

d African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), P.O. Box 10787-00100, APHRC Campus, Kitisuru, Nairobi, Kenya

Kanyiva Muindi

Evans gichana.

e County Government of Kisumu, P.O. Box 2738-40100, Kisumu, Kenya

Mike Davies

Surging amounts of waste are reported globally and especially in lower-income countries, with negative consequences for health and the environment. Increasing concern has been raised for the limited progress achieved in practice by diverse sets of policies and programmes. Waste management is a wicked problem characterised by multilayered interdependencies, complex social dynamics and webs of stakeholders. Interactions among these generate unpredictable outcomes that can be missed by decision makers through their understanding and framing of their context. This article aims to identify possible sources of persistent problems by focussing on what captures, shapes and limits the attention of stakeholders and decision-makers, drawing on the attention-based view from organisation theory. The theory describes the process through which issues and opportunities are noticed and how these are translated into actions, by focussing on the influencers at the individual, organisational and context scale. Views on issues and opportunities for waste management were collected in a series of fieldwork activities from 60 participants representing seven main types of stakeholders in the typical lower-middle income Kenyan city of Kisumu. Through a thematic analysis guided by the attention-based view, we identified patterns and misalignment of views, especially between government, community-based organisations and residents, which may contribute to persistent waste problems in Kisumu. Some point to detrimental waste handling practices, from separation to collection and treatment, as the main cause of issues. For others, these practices are due to a poor control of such practices and enforcement of the law. This study's major theoretical contribution is extending the application of attention theory to multi-stakeholder problems and to non-formalized organisations, namely residents and to the new field of waste management. This novel lens contributes a greater understanding of waste issues and their management in Africa that is relevant to policy and future research. By revealing the “wickedness” of the waste problem, we point to the need for a holistic and systems-based policy approach to limit further unintended consequences.

Graphical abstract

- • Attention-based view helps understand multi-stakeholder waste management problems.

- • Our analysis highlighted individual, social and contextual factors driving attention.

- • Household behaviour and government control are pointed as main source of the issues.

- • Misaligned scales in issues and moves across stakeholders must be tackled.

- • We rapport waste management wicked problem to multiple actors and agendas.

1. Introduction

Waste management is a global challenge ( Wilson and Velis, 2015 ) because of the significant fraction of greenhouse gas emissions generated by waste treatment and disposal ( Kaza et al., 2018 ), and a priority to be addressed to ensure sustainable production and consumption ( United Nations, 2020 ). The pressure is acute in low and lower-middle income countries, where growing amounts of waste caused by increased population ( Wilson and Velis, 2015 ), urbanization trends and economic development ( Modak et al., 2016 ) have produced alarming negative impacts, primarily on human health and the environment ( Ferronato and Torretta, 2019 ; Hyman, 2013 ). Lower-middle income countries account for about a third of the waste generated globally, with sub-Saharan African countries in particular projected to triple the amount of generated waste by 2050 ( Kaza et al., 2018 ). These countries are most affected by ineffective waste management, especially because of a lack of infrastructure, proper management planning as well as insufficient financial resources, technical expertise and public attitude ( Srivastava et al., 2015 ).

Kenya is one of the many countries in sub-Saharan Africa affected by the problem of waste ( Kaza et al., 2018 ). This study focusses on Kisumu, a typical example of a growing city in Kenya, which has experienced significant challenges in relation to insufficient waste management systems ( Gutberlet et al., 2017 ). In Kisumu, and Kenya more broadly, diverse policies have been developed and implemented to address the reduction and optimization of waste management ( World Health Organization, 2018 ). The Kenyan Solid Waste Management Strategy ( NEMA, 2015 ) intends to foster the uptake of efficient technology, yet technological solutions alone are likely to be insufficient to the problems of increased waste, as waste management is driven by multi-dimensional factors ( Guerrero et al., 2013 ).

A recent bill on waste management by the County Government emphasizes the importance of public participation and the collaboration with relevant stakeholders ( County Government of Kisumu, 2020 ); this resonates with the recommendation of previous research indicating that the multidimensional nature of waste management in Kisumu “requires the active participation of all relevant stakeholders including the City Board Management, civil society, NGOs, CBOs, waste private collectors and entrepreneurs” ( Sibanda et al., 2017 , p. 399). In other comparable contexts, the engagement of multiple stakeholders has been pursued in the past, especially in informal settlements. Public-private partnerships have also been recurrently explored ( Ma and Hipel, 2016 ), on the grounds that public provision of waste management is inferred to yield worse results in countries with lower GDP ( Simões and Marques, 2012 ); nevertheless the engagement of the private sector does not ensure successful results ( Simões et al., 2012 ). Some projects have also engaged residents and waste pickers in collaborative development of basic services with local governments (e.g. Zapata Campos and Zapata, 2013 ), yet many challenges are faced by these types of projects ( Kain et al., 2016 ).

Previous efforts have attempted to engage a wide set of stakeholders in the development of waste strategies in Kisumu. Nevertheless, both policy and research raise concerns about the limited impact that policies have achieved in practice ( Kain et al., 2016 ). Kain et al. (2016) highlight how a mismatch of views about waste may contribute to the problem. Through analysis of the effects of a plan for waste management in Kisumu, they inferred that policy developers' reframing of waste, from a dirty problem into a resourceful service, was not consistent with the views of other stakeholders, both those directly involved in waste management (such as waste pickers and residents), and those not directly involved (e.g. landlords or residents of some settlements). These other stakeholders did not share the policy developers’ view of change, and some prioritised coping with other difficulties. Ultimately this hindered the anchoring of the Kisumu waste management programme in a fully successful fashion, especially in some informal settlements ( Kain et al., 2016 ).

This study considers how theories of organisational attention could explain mechanisms that drive how stakeholders notice and process changes. Organisations hold understandings of problems, opportunities and the surrounding context which drive their actions towards (sustainable) change. In organisation studies these include collective action frames ( Blomsma, 2018 ) and the institutional logics perspective ( Arena et al., 2018 ; Gregori and Holzmann, 2020 ). Nevertheless, such understandings are not comprehensive and risk failing to capture critical dynamics. By contrast, theories of organisational attention suggest that organisations are problem-solving entities with limited attention; understanding the behaviour of organisations and their ability to adapt to change requires the understanding of how the attention of their decision makers is distributed and regulated ( Ocasio, 2011 ) for making sense of the environment and its changes ( Hoffman and Ocasio, 2011 ). A multitude of factors within an organisation determine if and how crises are identified, interpreted and addressed, as well as the consequences of the actions enacted (or not) to respond to them ( Ocasio, 1997 ).

A comparative and detailed investigation of how diverse local stakeholders understand the management of waste in Kisumu, and what should be changed, is still missing in our knowledge, despite some appreciable contributions (e.g. Kain et al., 2016 ). This study addresses that lack. We aim to identify what drives and shapes the attention of decision makers in order to add further insight about the discrepancies among stakeholder views on local waste management reported by Kain et al. (2016) . The objective is to find whether and how some of the criticalities and unintended consequences in waste management result from what drives the attention of relevant players, and therefore disparities of what they consider salient. In order to test the alignment of understandings, we engaged stakeholders to represent the diverse sectors involved, i.e. government, industry and trading, community-based and non-governmental organisations, academia, and residents’ associations.

The reminder of the article is structured with a preliminary summary of the Attention-Based View of the organiation (ABV), used to analyse the results of the fieldwork activities (section 2 ), followed by the methods for data collection and analysis, including a brief description of the case study (section 3 ). The results (section 4 ) present two main themes resulting from the analysis: stakeholder views on waste handling practices; and assessments of government's role in these. These themes are discussed by expanding on what constitutes an issue for the stakeholders involved, and the limits in the ways this is addressed, from which we argue that waste management is a ‘wicked problem’ (section 5 ). The key insights and contributions of the article are summarized in the conclusion (section 6 ).

2. Attention based view (ABV): theory and applications

This study draws on organisational research addressing “the socially structured pattern of attention by decision makers within an organisation” ( Ocasio, 1997 , p. 188). Diverse elements drive decision makers’ attention, according to a review of the literature ( Suzuki, 2017 ), including organisational goals, strategy and identity; characteristics of decision makers, individual or collective schemas, cognitive models of key decision makers; organisational positions and roles. These elements reflect that “attention is not a unitary concept but a variety of interrelated mechanisms and processes” ( Ocasio, 2011 , p. 1286). ABV is a theory of organisational decision-making and action developed by Ocasio. Drawing on Simon (1947) , Ocasio (2011) provides an explicit treatment of attention to explain organisational behaviour as a situated, variable, multilevel process that combines cognition and structure. Specifically, cognitive processes are engaged at both individual (i.e. the carrier of focussed attention) and social level (i.e. contextually shared understandings and values). Social, economic, and cultural structures operate in the organisation and determine how attention is distributed. For its multilevel approach, ABV is considered a cornerstone breaking engrained assumptions in the field ( Kaplan et al., 2001 ) and it has been used successfully to explain organisational decision-making processes, organisational change and management innovation, amongst others ( Ferreira, 2017 ). However, its application to understanding waste management has been limited to date.

Ocasio (1997 , p. 189, emphasis in original) defines organisational attention as the process of “noticing, encoding, interpreting, and focussing of time and effort by organisational decision-makers on both (a) issues (…) and (b) answers ”. Issues indicate the available repertoire of categories for making sense of the environment, which include problems and threats, as well as opportunities; whereas answers refer to the available repertoire of action alternatives, including proposals, routines, projects, programs, and procedures ( Ocasio, 1997 ). According to Ocasio's model ( Fig. 1 ), issues and answers are conveyed and distributed into specific procedures and communication channels, i.e. the formal and informal activities, interactions, and communications set up by the organisation to induce decision makers to action; these include meetings, reports and protocols. Attention is situated in these channels and therefore managers' attention is conditioned by the interactions between them ( Joseph and Ocasio, 2012 ).

ABV model; simplified version of the original one by Ocasio (1997) representing the process according to which (from left to right) issues and answers in the decision environment are shaped by attention structure and progressively elaborated through procedural and communication channels in order to guide decision makers towards the enactment of organisational moves. The arrows indicate the direction of the influences between the elements of the model.

The distribution of issues and answers into the channels is catalysed by attention structures, i.e. the social, economic, and cultural rules that govern the allocation of time, effort, and attentional focus of organisational actors in their decision-making activities (March and Olsen, cited in Ocasio, 1997 ). Attention structures include contextual rules about how to interpret and operate in reality; players with their skills, beliefs and values; roles and relations within and outside the organisations; and resources necessary for the organisation to perform activities.

Procedural and communication channels as well as attention structures determine the salience of the issues and answers to be attended to; although potentially confusing in their naming, they introduce concrete actions and context respectively in the decision-making process ( Barnett, 2008 ).

These mechanisms guide decision makers towards the definition of organisational moves , i.e. “the myriad of actions undertaken by the firm and its decision-makers in response to or in anticipation of changes in its external and internal environment” ( Ocasio, 1997 , p. 201).

In this study, we apply Ocasio's theory to explore issues , answers and moves as the focus of our investigation. Issues and answers are of paramount importance, because these two “together constitute the corporation's agenda and are central to adaptation and change” ( Joseph and Ocasio, 2012 , p. 637). Therefore, they are envisaged here as principal proxies for the identification of critical elements. The exploration of moves is likewise relevant in progressing towards issues and answers as well, because, once enacted, the organisational move becomes part of the environment of decision making, and in turn inputs to the construction of subsequent organisational moves ( Ocasio, 1997 ). Also known as ‘automorphism’, such use of past strategies may institutionalize solutions and therefore gain legitimacy not only within the actant organisation but also in the wider field ( Schwartz, 2009 ).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. the case study of solid waste management in kisumu.

This study addresses the issues and solutions envisaged by the stakeholders of waste management in the Kenyan county of Kisumu ( Fig. 2 ), where poor health and the degraded environment are associated with improper disposal of municipal solid waste ( County Government of Kisumu, 2019 ). Population growth, urbanization and lifestyle change, accessibility and illegal dumping are some of the socio-economic and geographical conditions putting pressure on the management of waste for the county, as well as for the wider country ( Henry et al., 2006 ).

Map of Kisumu county.

The county of Kisumu is inhabited by 1.1 million ca. people ( Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2019 ), with an overall population growth trend projected for the next decades ( United Nations, 2019 ). About half of the population resides in urban areas, especially in Kisumu city, which is the third largest city in Kenya ( Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2019 ). About 60% of the urban population is estimated to live in slums and peri-urban settlements ( United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2005 ), which are densely populated areas with limited access to basic services, including piped water ( Frediani, 2015 ), electricity, sanitation, and solid waste management services ( Onyango et al., 2013 ). In the slums, most household waste remains uncollected, mostly because of accessibility and financial constraints ( Munala and Moirongo, 2011 ), and is dumped along roads, alleyways or in vacant lots, leading to appalling conditions ( Gutberlet et al., 2017 ).

Kisumu County generates about 200–450t of solid waste per day, mostly composed of organic material, e.g. food waste ( County Government of Kisumu, 2019 ), in line with other low- and middle-income countries ( Modak et al., 2016 ). Trends of increased waste generation are associated with lifestyles changes ( Munala and Moirongo, 2011 ), possibly in conjunction with urbanization.

The generated waste is handled by both public and private stakeholders. The Kisumu Integrated Solid Waste Management Plan (KISWaMP) combines centralized modes of service provision with grassroots initiatives for expanding the coverage of waste management services to informal settlements where open pits are widely used to manage solid waste ( County Government of Kisumu, 2017 ). Waste is either collected, disposed of in collection stations, dumped or burned. The door-to-door collection is operated by private collectors in affluent neighbourhoods, whereas community-based organisations (CBOs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), as well as individual waste scavengers, are mostly operative in the informal settlements. CBOs are groups of individuals who organise themselves to provide waste services in their (usually poor) neighbourhoods; this represents for many an opportunity for both income and a clean environment for the community ( Aparcana, 2017 ).

Waste in the small city centre and the markets is collected by the county government. Only about 20%–40% of the total generated waste is collected for disposal at the city's open landfill ( Dianati et al., 2021 ). Open burning of waste for more than 50 years, only two km from the capital centre ( Awuor et al., 2019 ), at the so-called Kachok dumpsite has raised concerns around insecurity, public health, and environmental degradation ( Sibanda et al., 2017 ). Efforts towards relocating this overflowing dumpsite to a larger site farther away from the city centre have so far not been very successful, mainly because of residents' resistance.

The majority of waste remains uncollected and mostly illegally-disposed, namely openly burnt or dispersed in the environment in garbage heaps and litter everywhere ( Munala and Moirongo, 2011 ), such as alongside roads or on vacant land ( Sibanda et al., 2017 ). Improper waste disposal and management in Kisumu are associated with scarce human and financial resources, poor organisational structures, inadequate legislation and weak enforcement, poor public attitude and low awareness of waste management ( County Government of Kisumu, 2017 ).

3.2. Engaging stakeholders across multiple sectors

The study is informed by a set of nine fieldwork activities, including workshops, focus groups and interviews, held in Kisumu in July 2019 with stakeholders of local waste management. Two workshops were held for a variety of stakeholder participants to agree first on a local challenge to be addressed in a bid for funding; the challenge agreed upon was municipal solid waste management. Subsequent focus groups and interviews aimed to collect the views and experiences of stakeholders on this challenge. The participants represented different sectors, specifically civil servants in the county government, academic lecturers, industry and trading associations, CBOs and NGOs, and representatives of the local resident community.

Purposive sampling was used for the invitation of the participants, based on their knowledge of the waste management and sector. Participants were gathered in groups according to their sector (except for the first workshop which covered multiple sectors), with the aim to elicit ‘group thinking’ (Brown, 1999; cited in Robson, 2002 ) needed to identify patterns of attention distribution and organisational structures within sectors and clusters of organisations. The local government sector was represented by civil servants from departments addressing topics overlapping with waste management, including environment, climate change, energy and urban development. Academics invited were knowledgeable about waste management either through their teaching or research work. A further group of participant mobilizers were individuals from CBOs or NGOs, who reside in Kisumu. A participant from the sugarcane industry – a main industry for the local economy ( County Government of Kisumu, 2017 ) – and two from trading associations attended the focus groups; although limited in number their views complemented the wider picture of waste management. Finally, there were resident association representatives from underserved residential areas, mostly informal settlements in the city. All the participants are operative in the Kisumu county area. With a totalling 60 attendees, the number of participants in each research activity and their sector are summarized in Table 1 ; abbreviations for fieldwork activities are used to attribute quotes in the Results section, alongside an abbreviation to indicate the specific (male or female) respondent consistently with the transcripts of the activities (e.g. Resident, FR1).

Number and represented sectors of the participants of each research activity.

| Activity number | Activity abbreviation | Sectors represented by the participants | Number of participants (excluding staff) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bid1 | Local government, Academia | 9 |

| 2 | Bid2 | 6 | |

| 3 | CBOs/NGOs | CBOs and NGOs | 9 |

| 4 | Industry1 | Industry and trading | 2 |

| 5 | Government1 | Local government | 10 |

| 6 | Government2 | Local government | 8 |

| 7 | Industry2 | Industry and trading | 1 |

| 8 | Academia | Academia | 8 |

| 9 | Residents | Resident associations | 7 |

Each activity started with the participants being invited to introduce themselves and to provide an example of a relevant project on waste management, in which they have been involved. The set of questions for each focus group and interview was designed to inform different streams of the research and including: the goals of the stakeholder groups; barriers and enablers for the achievement of the goals; tensions between organisations and procedures to solve these; decision making processes; evidence use and types; and indicators of success. The number and type of questions were adapted according to the responses and the flow of the conversation in each activity.

The language of all fieldwork activities was English, except for Activity 9 with residents, in which both English and Swahili were used, with local staff members interpreting for the non-Swahili speaking researchers. All the activities were audio recorded with the approval of the participants, all of whom agreed with and signed the informed consent describing the purpose of the study and the research activity; anonymized verbatim transcripts (translated from Swahili where applicable) were provided to the researchers for their analysis informing this study.

3.3. Thematic analysis of issues and moves

The transcripts of the fieldwork activities were subjected to the six-phase thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2006) , a well-established method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns within data (schema in Table 2 ). Thematic analysis is widely used in organisational research because it facilitates “the kind of sensitive, nuanced examination of organisational phenomena that qualitative research seeks to achieve” ( King and Brooks, 2018 , p. 233).

The six phases of thematic analysis. Reproduced from Braun and Clarke (2006) .

| Phase | Description of the process |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising yourself with your data | Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas. |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collating data relevant to each code. |

| 3. Searching for themes | Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (Level 1) and the entire data set (Level 2), generating a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis. |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each theme. |

| 6. Producing the report | The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis. |

After having familiarized with the transcripts (Phase 1 in Table 2 ), the researchers associated codes to reflect the main features described by the text, a process known as coding (Phase 2). Coding followed a hybrid inductive and deductive approach; a preliminary codebook provided deductive (or predetermined) categories reflecting the main premises of the ABV theory for subsequent inductive (or bottom-up) coding, according to which codes are generated to reflect the contents of the data. The coding was performed in NVivo by two coders asynchronously, the work of whom was eventually integrated.

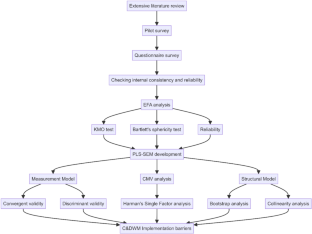

The set of codes was eventually analysed and reviewed for identification of themes (Phases 3 to 5). The themes presented in the Results are elaborated predominantly from the codes capturing two main elements of the ABV model, i.e. issues and organisational moves, when participants explicitly address waste management. The codes informing the themes are visualized in the Results section in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 , for communication purposes (Phase 6) and transparency ( Gioia et al., 2013 ).

Thematic analysis of the theme ‘waste handling issues and their change’ (on the right). The theme is associated to a set of codes identified in the analysis of the transcripts of the research activities (on the left), which are grouped for convenience (in the centre).

Thematic analysis of the theme ‘poor government control and difficult political context’ (on the right). The theme is derived from a set of codes (on the left), which are grouped for convenience (in the centre).

Frequency of references within codes or themes occasionally reported in this article are to be interpreted as a potential beacon of interest for some participants on a specific topic. Reference counts may be affected by multiple conditions and in this qualitative study they are to be considered a potential topic to explore further in data ( King and Brooks, 2018 , p. 227).

Two main themes are identified from the analysis: the practice of managing waste, from its generation and separation to collection and treatment; and the practice of ensuring that waste is managed appropriately. The first theme focusses on what constitutes an issue or an opportunity when waste is handled, and how these issues are addressed by the involved stakeholders, such as households, businesses and service providers. The second theme focusses on the ways in which suboptimal, or illegal, waste handling practices are addressed by the government, including expectations and moves for encouraging or enforcing change. Together, the two themes address reciprocal – and often unmet – expectations of appropriate behaviours and roles between two main groups of players (the producers and mangers of waste on the one side, and the government on the other), revealing the different foci and structures driving their attention.

4.1. Issues and moves in handling waste

Local waste management is complex, and connected to a wider set of challenges, most notably with health and the environment:

“In Africa we've got all our challenges integrated” (CBOs/NGOs, MR7)

The ways in which waste is handled represent the most recurrent topic, and possibly the priority to be addressed in participants’ description of main issues. The following subsections summarise what participants reported about types of detrimental practices, from waste generation to final treatment, as well as the envisaged solutions for their change. The codes generated from the thematic analysis and associated with this theme are visualized in Fig. 3 .

4.1.1. The issues

The most recurrent issues raised across the fieldwork were numerous inadequate or illegal practices of waste handling, and their distribution across many actors. The various stakeholders implicated include: industries with inadequate waste treatment infrastructure (e.g. using burning chambers as incinerators, industry treatment plants); clinics dumping medical waste and even human remains in undesignated areas; waste collectors providing unauthorized services or inappropriately mixing separated waste; and – frequently – households separating their waste improperly, or disposing of it in public spaces (e.g. on roads, in markets). Participants associate significant negative consequences with inadequate waste handling, including both practical limits to the effectiveness of waste management operations, and health implications for operators and the wider population (e.g. because of contaminated water).

The causes of improper waste handling are attributed to multiple reasons and conditions, starting from a lack of the fundamental assets and infrastructure, such as skips, bins and compound facilities in clinics. Likewise, limited financial resources may constrain access to waste management services, namely for clinics or some low-income households, who cannot afford collection fees:

“That is one place skip don't reach there, there are no bins so people just manage their waste the way they think is best for them. So, they burn it.” (Bid2, MR5)

Residents are reported to be uninformed about appropriate ways of handling waste and the consequences of this for health, such as of flooding spreading diseases, because of drainage blocked by dumped waste.

Social norms and routines are also frequently pointed to as significant sources of issues. Improper disposal may hence be rooted in habits. For instance, participants believe that migrants from the countryside to the city are accustomed to disposing of organic waste that is generally biodegradable, and therefore fail to adapt to the need to dispose of non-organic waste in different ways. Moreover, a sense of ownership towards waste management and public spaces plays a role in these behaviours. Shared public understandings of responsibilities have traditionally framed waste as “government's business”, although this is now inconsistent with current regulations:

“if you look at even the waste management regulations it is very clear that it is the responsibility of the generator of that waste to manage it up to the point provided for the government. (…) Anywhere in between here is illegal dumping. So that has been the challenge that for them because also we have very weak infrastructure systems” (Government2, MR1)

In contrast to private houses, which are kept clean, roads and other common spaces are “nobody's land” (CBOs/NGOs, MR4) and waste is often carelessly left there. Traders, for instance, are blamed by those in the government focus group for their attitude to illegal dumping in their areas which may be convenient in the short run, rather than contributing to long-term solutions to the issue. This apparent carelessness provides, and to an extent justifies, jobs to waste collectors:

“<< I will throw this bottle anywhere because the county has employed someone who I assume is supposed to clean the city >>. (…) So, it is more an attitude problem that we are trying to deal with.” (Government2, MR1)

The waste workers are heavily stigmatised (for instance, being referred to as “warthogs”). Some participants want to see this stigma change (Resident MR3). Yet for others, appreciation of these workers' contribution to waste management remains an “impossible attitude” (Resident, MR2):

“[Hotels who refused to pay young task force] think these are just people for ‘takataka’ (Swahili: rubbish collectors)” (Resident, MR1)

Some participants point to meaning and priorities generally attributed to careful ways of handling waste, with a widely shared perception of waste as annoyance rather than a resource – although with notable exceptions reported in the next subsection.

Local policies and regulations as well as initiatives intended to trigger change towards sustainable waste disposal and effective management are in place, and indeed recurrently mentioned especially by the governmental officers, as well as by the industry representatives. Nevertheless, a lack of compliance, and resistance to change, is also frequently reported, notably being more often raised by the governmental sector (Government2 focus group and in the Bid2 workshop session in particular). Residents and representatives of CBOs and NGOs tended to frame these behaviours as disadvantageous (rather than non-compliant) and refer to them to a lesser extent.

4.1.2. The moves

In response to the apparent “illegal” or disadvantageous practices, several possible or enacted moves are reported by the participants, both for a better understanding of the issues, and for triggering change towards more effective waste handling. Local people (e.g. households, landlords, farmers) are often identified, especially by government representatives, as the main sources of issues. This leads to the view that better waste handling should be addressed by discovering the reasons for which they dump, or separate waste improperly, and then by triggering a change in their behaviours.

This behavioural change is proposed through strategies of either encouragement or enforcement. Encouraging strategies include the provision of incentives, e.g. tokens, for reshaping the perceived value of waste and of sorting it. In particular, participants frequently talk of “sensitising” through the provision of information, to raise awareness, and to educate the community and the waste collectors. The suggested means include the engagement of local champions, exhibitions and shows, developing educating platforms, and engaging in practical activities such as clean-ups with the local community. Some of these latter activities have been incentivised and sponsored by governmental organisations, as a proxy for encouraging participation of multiple stakeholders in waste management, and ideally shifting the perception of waste handling away from “the exclusive responsibility of government” (Government2, MR1). Indeed, the governmental sector together with CBOs (and to some extent the residents) mostly advocate sensitization and awareness raising around the importance of a clean environment.

Some participants acknowledge challenges in behavioural change. For instance, they say that extensive time may be required for households to routinise proper waste separation, thus requiring supplementary workforce in separating waste in the meantime, as suggested by a governmental participant. Nevertheless, behavioural change at household level is deemed insufficient by another participant, as the waste management system is not effective:

“(They) are trying to do separation at source and then the same county mixes the waste going to the dumpsite, waste being mixed then again, the waste pickers now do the sorting. You see, it is a bigger challenge.” (CBOs/NGOs, MR3)

This implies that other actors besides households should be encouraged towards better waste handling practices to achieve systemic change. This wider realm of stakeholders to be engaged and connected, most notably waste collectors, is recognized by a participant from the opening workshop:

“(…) you need to look at this holistically, about the issues that are there because you cannot manage waste when you don't have a proper schedule on how you need to collect it, and you cannot have a proper schedule also when you don't have people who are collaborating or cooperating with you to make the environment clean. So, all this boils to one thing that there must be public participation in the entire issue, the government does its role even if they are availing the skips and collection points and whatever, you must also be a co-operator, in terms of from your household, how you are bringing in this waste. The waste collectors, I mean the private, the private waste collectors are very important people, stakeholders in these aspects. Some of them have a proper way of even scheduling their collection either once or twice a week and they know the people, the households where they collect from. So, with time as you try and educate them and talk to them; they will be able to tell you, you can be able to assist us by doing this or that. So, from there you will also be able to learn and get something to know that if this and this is done, we shall succeed from this point of view.” (Bid2, MR1)

Partnerships and collaborations with many stakeholders are often proposed as a move to address the waste once generated, but there is less attention as to what could change behaviours to prevent it arising in the first place.

Networking players is also suggested for maximizing the residual value of waste. For instance, by the collection of organic waste (e.g. from hotels or schools) for use in the production of energy, thereby fostering the local economy. Circular approaches are recommended to supersede landfilling, currently a convenient option which discourages waste separation. Government could make such waste management approaches lucrative and attractive for private entrepreneurs through the incentivizing provision of infrastructure and financial resources, e.g. funding or tax relief for fostering recycling and youth employment, compostable bag production, or a shift to non-burn-technology for medical waste. Incentivizing actions are complemented by discouraging moves, ranging from the removal of services (e.g. skips from where these are abused by waste collectors and clinics), to better regulation, which is favoured by governmental stakeholders, ideally for limiting illegal dumping, inadequate waste separation, or ineffective recycling in industries.

Other types of moves include stronger enforcement, new policies, inspections, and de-registrations (i.e. of private waste collectors from networks or of providers allowed by the public sector when non-compliance is spotted). Inspections are recommended to inform on the misuse of skips and represent an “easier” way to ensure legitimacy in private clinics, with apparently successful results. Similarly, a resident suggests enforcing the principle of shared responsibility within the community, for example, by making citizens surveillant of disposal habits in a circle of close neighbours.

A final area of attention is the enforcement of a ban on the production of some plastic items, which raises conflicting views. The ban is said by an industry representative to have resulted from lobbying pressure on the government by environmental groups and other stakeholders to regulate the market producing waste, especially the high number of water-bottling companies. Banning the production of plastic bottles risks disincentivising recycling, leading to more plastics disposed of in the environment (CBOs/NGOs, MR7). An alternative to the ban is developed by the industry sector in an action plan approved by the government, for the collection of used plastic bottles for remanufacture.

4.2. Poor governmental control and the difficult political context

The inadequate practices of waste handling mainly reveal the view of issues and moves from the government perspective. The role of governmental stakeholders is highly relevant to waste management, for they have the legitimacy and ability to define the trajectories of issue resolution. Nevertheless, certain groups of participants often contested the effectiveness of their actions, seeing unmet expectations and thus representing a source of issues to be addressed in waste management. The codes informing this second theme are visualised in Fig. 4 .

This issue is raised most frequently by resident representatives and CBOs and NGOs as well as in the initial workshop; few or any references are coded across the other stakeholders. Many expect the government to address waste management better and more intensively by ensuring order through the enforcement of the law, and through implementing policies for change. Issues of order are raised with respect to compliance and illegal actions, to clarifications about procedures to be provided to the community, and to effective collection of separated waste. Policies are reported to be generic, with the resulting risk of amplifying the challenges due to lack of infrastructure.

Urban planners are accused of creating inadequate conditions, failing to deliver on or anticipate, for instance, convenient solutions for the local community; the reconfiguration of urban activities deriving from disruptive interventions; increased pressure on service from population growth over time; or missing designated areas for solid waste especially in informal settlements, which may encourage illegal dumping (Bid2, MR4):

“(W)hat is our planning system? Who is planning for us that I am generating waste in my house, what next should I do with it? should I throw it to my neighbors, should I throw it on the roadside or should I take it somewhere that our urban councils or county governments in a big or smaller way, I am trying to dig out that the planning aspect of it is a major issue that we can be able …. help us address this issue. After generating this waste in my house is there any place that is designated closer to where I am living, where I can take my waste then? Or must I go all the way seven kilometers where Kachok dumpsite is located? So, these are the queries.” (Resident, MR1)

Discussions about unmet expectations, contested actions, and perceived failings reveal possible sources of constraints for the government. These reflect the attentional structures and issues faced and reported by their representatives, including contextual political instabilities, rules of the game for politicians, and salience attributed by decision makers to different stakeholders. Politicians and governmental actors’ personal agendas and priorities are held to drive their moves, with respect to ongoing plans and projects:

“So, in the governor's directive now, because in his manifesto he promised Kisumu people that he will do away with Kachok. And he is already getting rid of Kachok with now timelines.” (Government2, MR4)

Our analysis suggests that two main players attract the attention of the local government and politicians: the national government and the local community.

On the one hand, local government is part of a larger structure with a top-level management at a national scale. The relationship and social norms across representatives of the country's two-tier governmental structure is reported to generate conflicts of interest instead of symbiotic working. Policies intended to bring about sustainable change require the approval of political decision makers, which may result in lobbying, and even bribery and corruption (Government1, MR8).

Likewise, some of the major issues and answers regarding waste management, including the creation of a dumpsite, may be envisaged as opportunities for monetary advantage, said to attract the attention of the political class and higher governmental levels, and thus becoming their interest rather than of the wananchi 's (Swahili: citizens'):

“(…) Waste management is not for the poor, it is for the rich.” (Government1, MR3)

On the other hand, the importance for politicians to produce visible and memorable outcomes attracting the attention of the voting local community (e.g. a borehole, a hospital) is a driving force in decision-making processes. This is supported by discussion regarding the allocation of budget to the departments at governmental level. This is observed to be often on the basis of the visibility of the actions (e.g. creating dispensaries or drilling boreholes, rather than cleaning the market), serving as proxies for increasing the chances of re-election for a political candidate.

“Unfortunately, decisions made at this level, a lot of it is driven by politics and politics is about perception. When I build a hospital or dispensary then I stand a chance of people seeing what I have done [… and be re-elected …]. When I clean a market, the traders may have a feeling of that impact. But even then, because it is something recurrent, tomorrow when you come back it is already dirty. So, it doesn't stick in mind. So that dispensary is more long lasting or a road or an ECD center. So, in order of priority they only seem to get the bowl first then whatever remains is given to the rest of us.” (Government2, MR4)

The dynamics of these two poles indicate how the moves operated by government to attract attention of decision makers, or other salient players, may in turn contribute to problems for waste management.

Notably, unlike the set of moves fostering change of practices of waste generators and handlers, there are few actions suggested to address these political issues, constraining rules of the game, procedure and attention structures of local government.

5. Discussion

The results of the study confirm how complex the system of waste management is in Kisumu, engaging a number of different stakeholders who pursue a variety of goals through their moves (summary of issues and corresponding moves in Appendix B ). This general outcome and several of the specific dynamics resonate with previous studies in this context, most notably with the issues of deprivation, financial scarcity, poor planning ( Kain et al., 2016 ), poor government control and enforcement ( County Government of Kisumu, 2019 ), ambiguity in responsibilities, ( County Government of Kisumu, 2019 ; Gutberlet et al., 2017 ), poor public attitude to proper waste management and infrastructural inadequacy ( County Government of Kisumu, 2019 ; Gutberlet et al., 2017 ; Kain et al., 2016 ; Munala and Moirongo, 2011 ; Sibanda et al., 2017 ).

Our thematic analysis identified two contrasting themes, corresponding to an opposite attribution of responsibility and expected actions from other stakeholders ( Guerrero et al., 2013 ); in summary these themes are inadequate waste handling according to the governmental sectors, and ineffective control mostly according to the local community. In our view, these contrasting themes largely emerge through the identification of multi-level drivers of attention enabled by ABV, and which contribute to explaining the discrepancy in views and perceptions of success in policy local implementations.

5.1. What constitutes inadequate practices and the limits of sensitisation?

The non-compliance of households in handling waste and resistance to positive change emerged in our first theme, and, consistently with literature ( Sibanda et al., 2017 ), is more recurrently reported by participants from the governmental sector. In our view, this pattern is possibly associated with the area of competence of our participants, and the way success is measured, i.e. the extent to which one of their main outputs (policies) are abided by.

A multitude of moves are proposed or reported as enacted by the participants to change residents' and other waste generators’ behaviours. Raising awareness and “sensitisation” are dominant reported moves by local government, and intended to trigger change in waste handling practices. Nevertheless, our results suggest that information may actually be available to the waste handling actors.

Behavioural science theory and research highlights that these information-provision based approaches are not necessarily sufficient to change behaviour ( Gatersleben et al., 2002 ; Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002 ), nor are they the only behaviour change approaches available to policy makers ( Michie et al., 2011 ; West et al., 2019 ). Information and sensitisation typically aim to change people's understanding and attitudes, but it is well-established that there are gaps between forming an attitude, forming an intention to act, and actually acting ( Armitage and Conner, 2000 ).

A multitude of additional factors affect this practice and characterise the environment of the waste handlers, including rooted habits, financial and infrastructural scarcity, convenience and situated circumstances, perceived ownership and diffused responsibility. Although non-compliant with the law, the ways in which waste is disposed represent accessible solutions to other sets of more relevant or pressing issues.

In order to initiate a desired behaviour, such as sorting waste at source, or to stop an undesired behaviour, such as dumping on the roadside, people need to have sufficient capability (physical and psychological ability, e.g. skills and knowledge), opportunity (features of the physical and social environment, e.g. infrastructure and social norms) and motivation (reflective and automatic processes, e.g. beliefs and habits). These factors form the COM-B model of behaviour ( Michie et al., 2011 ). Stakeholders mentioned examples of each factor as a barrier to proper waste management. For example, a lack of knowledge about how to dispose of waste correctly (capability), a lack of resources such as easy-to-reach bins and skips to dispose of waste (opportunity), and beliefs that waste management is someone else's responsibility (motivation). Successfully changing behaviour in complex systems is likely to require a combination of different intervention types, including education, incentivisation, training, environmental restructuring ( Michie et al., 2011 ), and delivered through multiple policy actions, e.g. fiscal measures, legislation, service provision, communications ( Michie et al., 2009 ).

Nevertheless, evidence about if, and how, households’ environment and behaviours are explored by governmental players to make decisions is limited. Furthermore, consensus on how change towards more sustainable patterns of consumption occurs is not reached in scientific literature; the critiques that some dominant behaviour change approaches receive (e.g. Shove, 2010 ) reinforce how challenging such a necessary change in the way people frame and carry normality is, and major efforts are required to envisage and develop more robust, effective moves.

5.2. Structural determinants of government

Participants often attribute substantial if not sole responsibility for addressing waste management to the government. This interpretation may derive from former governmental arrangements, preceding the establishment of Kenyan Environmental Management and Coordination Act in 1999, which reallocated environmental responsibilities ( The Republic of Kenya, 1999 ). Despite the declared intentions and moves of engaging the wider set of stakeholders, the role of government will likely remain central in setting goals and coordinating actions.

Nevertheless, our analysis showed few suggested moves to change the way government acts (see Appendix B ). Possible reasons for this include the potentially more visible nature of issues associated with resident behaviours, and the difficulty of envisaging solutions to possibly perennial problems characterising government attention (e.g. political interests, pleasing voters, two-tier governance and budget constraints). Our results suggest how the capability of county government to trigger change is bounded by structural and procedural determinants across two poles attracting its attention, i.e. the top management and the local community to serve. An issue is salient when it “resonates with and is prioritised by management” ( Bundy et al., 2013 , p. 353). Nevertheless, the goals of the top management may not necessarily capture the changes important to the voting population. Bansal et al. (2018) elaborate on how organisations may fail to identify latent issues (especially for sustainability) because of the lack of procedural or communication structures to notice them, more specifically because of the inconsistency of scale of the processes that generate the issues.

The issue of scale is important, as in Kisumu the longer-term view of government that elaborates extensive plans and programmes appears temporally misaligned with issues for the local community affecting their shorter-term, or even daily, routines. On one side of the spectrum, the county government pursues strategies intended to meet environmental targets scheduled in five or even 35-year plans; whereas, on the other side of the spectrum, residents report on routinised habits of dealing with cooking waste, market shopping, and corporeal needs. Business, CBOs and NGOs fall in between the previous two, while seeking profits and economic sustainability over the following financial years.