Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 October 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

A literature review is a discussion of the literature (aka. the "research" or "scholarship") surrounding a certain topic. A good literature review doesn't simply summarize the existing material, but provides thoughtful synthesis and analysis. The purpose of a literature review is to orient your own work within an existing body of knowledge. A literature review may be written as a standalone piece or be included in a larger body of work.

You can read more about literature reviews, what they entail, and how to write one, using the resources below.

Am I the only one struggling to write a literature review?

Dr. Zina O'Leary explains the misconceptions and struggles students often have with writing a literature review. She also provides step-by-step guidance on writing a persuasive literature review.

An Introduction to Literature Reviews

Dr. Eric Jensen, Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick, and Dr. Charles Laurie, Director of Research at Verisk Maplecroft, explain how to write a literature review, and why researchers need to do so. Literature reviews can be stand-alone research or part of a larger project. They communicate the state of academic knowledge on a given topic, specifically detailing what is still unknown.

This is the first video in a whole series about literature reviews. You can find the rest of the series in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

Identify Themes and Gaps in Literature (with real examples) | Scribbr

Finding connections between sources is key to organizing the arguments and structure of a good literature review. In this video, you'll learn how to identify themes, debates, and gaps between sources, using examples from real papers.

4 Tips for Writing a Literature Review's Intro, Body, and Conclusion | Scribbr

While each review will be unique in its structure--based on both the existing body of both literature and the overall goals of your own paper, dissertation, or research--this video from Scribbr does a good job simplifying the goals of writing a literature review for those who are new to the process. In this video, you’ll learn what to include in each section, as well as 4 tips for the main body illustrated with an example.

- Literature Review This chapter in SAGE's Encyclopedia of Research Design describes the types of literature reviews and scientific standards for conducting literature reviews.

- UNC Writing Center: Literature Reviews This handout from the Writing Center at UNC will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

- Purdue OWL: Writing a Literature Review The overview of literature reviews comes from Purdue's Online Writing Lab. It explains the basic why, what, and how of writing a literature review.

Organizational Tools for Literature Reviews

One of the most daunting aspects of writing a literature review is organizing your research. There are a variety of strategies that you can use to help you in this task. We've highlighted just a few ways writers keep track of all that information! You can use a combination of these tools or come up with your own organizational process. The key is choosing something that works with your own learning style.

Citation Managers

Citation managers are great tools, in general, for organizing research, but can be especially helpful when writing a literature review. You can keep all of your research in one place, take notes, and organize your materials into different folders or categories. Read more about citations managers here:

- Manage Citations & Sources

Concept Mapping

Some writers use concept mapping (sometimes called flow or bubble charts or "mind maps") to help them visualize the ways in which the research they found connects.

There is no right or wrong way to make a concept map. There are a variety of online tools that can help you create a concept map or you can simply put pen to paper. To read more about concept mapping, take a look at the following help guides:

- Using Concept Maps From Williams College's guide, Literature Review: A Self-guided Tutorial

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix is is a chart you can use to help you organize your research into thematic categories. By organizing your research into a matrix, like the examples below, can help you visualize the ways in which your sources connect.

- Walden University Writing Center: Literature Review Matrix Find a variety of literature review matrix examples and templates from Walden University.

- Writing A Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix An example synthesis matrix created by NC State University Writing and Speaking Tutorial Service Tutors. If you would like a copy of this synthesis matrix in a different format, like a Word document, please ask a librarian. CC-BY-SA 3.0

- << Previous: Case Study Design

- Next: Quantitative Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:51 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Service update: Some parts of the Library’s website will be down for maintenance on August 11.

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

Literature Reviews: Types of Clinical Study Designs

- Library Basics

- 1. Choose Your Topic

- How to Find Books

- Types of Clinical Study Designs

- Types of Literature

- 3. Search the Literature

- 4. Read & Analyze the Literature

- 5. Write the Review

- Keeping Track of Information

- Style Guides

- Books, Tutorials & Examples

Types of Study Designs

Meta-Analysis A way of combining data from many different research studies. A meta-analysis is a statistical process that combines the findings from individual studies. Example : Anxiety outcomes after physical activity interventions: meta-analysis findings . Conn V. Nurs Res . 2010 May-Jun;59(3):224-31.

Systematic Review A summary of the clinical literature. A systematic review is a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular clinical issue. The researchers use an organized method of locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature on a particular topic using a set of specific criteria. A systematic review typically includes a description of the findings of the collection of research studies. The systematic review may also include a quantitative pooling of data, called a meta-analysis. Example : Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Clin J Oncol Nurs . 2010 Aug;14(4):E45-55.

Randomized Controlled Trial A controlled clinical trial that randomly (by chance) assigns participants to two or more groups. There are various methods to randomize study participants to their groups. Example : Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial . Barrett B, et al. Ann Fam Med . 2012 Jul-Aug;10(4):337-46.

Cohort Study (Prospective Observational Study) A clinical research study in which people who presently have a certain condition or receive a particular treatment are followed over time and compared with another group of people who are not affected by the condition. Example : Smokeless tobacco cessation in South Asian communities: a multi-centre prospective cohort study . Croucher R, et al. Addiction. 2012 Dec;107 Suppl 2:45-52.

Case-control Study Case-control studies begin with the outcomes and do not follow people over time. Researchers choose people with a particular result (the cases) and interview the groups or check their records to ascertain what different experiences they had. They compare the odds of having an experience with the outcome to the odds of having an experience without the outcome. Example : Non-use of bicycle helmets and risk of fatal head injury: a proportional mortality, case-control study . Persaud N, et al. CMAJ . 2012 Nov 20;184(17):E921-3.

Cross-sectional study The observation of a defined population at a single point in time or time interval. Exposure and outcome are determined simultaneously. Example : Fasting might not be necessary before lipid screening: a nationally representative cross-sectional study . Steiner MJ, et al. Pediatrics . 2011 Sep;128(3):463-70.

Case Reports and Series A report on a series of patients with an outcome of interest. No control group is involved. Example : Students mentoring students in a service-learning clinical supervision experience: an educational case report . Lattanzi JB, et al. Phys Ther . 2011 Oct;91(10):1513-24.

Ideas, Editorials, Opinions Put forth by experts in the field. Example : Health and health care for the 21st century: for all the people . Koop CE. Am J Public Health . 2006 Dec;96(12):2090-2.

Animal Research Studies Studies conducted using animal subjects. Example : Intranasal leptin reduces appetite and induces weight loss in rats with diet-induced obesity (DIO) . Schulz C, Paulus K, Jöhren O, Lehnert H. Endocrinology . 2012 Jan;153(1):143-53.

Test-tube Lab Research "Test tube" experiments conducted in a controlled laboratory setting.

Adapted from Study Designs. In NICHSR Introduction to Health Services Research: a Self-Study Course. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/ihcm/06studies/studies03.html and Glossary of EBM Terms. http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/glossary/index.htm#top

Study Design Terminology

Bias - Any deviation of results or inferences from the truth, or processes leading to such deviation. Bias can result from several sources: one-sided or systematic variations in measurement from the true value (systematic error); flaws in study design; deviation of inferences, interpretations, or analyses based on flawed data or data collection; etc. There is no sense of prejudice or subjectivity implied in the assessment of bias under these conditions.

Case Control Studies - Studies which start with the identification of persons with a disease of interest and a control (comparison, referent) group without the disease. The relationship of an attribute to the disease is examined by comparing diseased and non-diseased persons with regard to the frequency or levels of the attribute in each group.

Causality - The relating of causes to the effects they produce. Causes are termed necessary when they must always precede an effect and sufficient when they initiate or produce an effect. Any of several factors may be associated with the potential disease causation or outcome, including predisposing factors, enabling factors, precipitating factors, reinforcing factors, and risk factors.

Control Groups - Groups that serve as a standard for comparison in experimental studies. They are similar in relevant characteristics to the experimental group but do not receive the experimental intervention.

Controlled Clinical Trials - Clinical trials involving one or more test treatments, at least one control treatment, specified outcome measures for evaluating the studied intervention, and a bias-free method for assigning patients to the test treatment. The treatment may be drugs, devices, or procedures studied for diagnostic, therapeutic, or prophylactic effectiveness. Control measures include placebos, active medicines, no-treatment, dosage forms and regimens, historical comparisons, etc. When randomization using mathematical techniques, such as the use of a random numbers table, is employed to assign patients to test or control treatments, the trials are characterized as Randomized Controlled Trials.

Cost-Benefit Analysis - A method of comparing the cost of a program with its expected benefits in dollars (or other currency). The benefit-to-cost ratio is a measure of total return expected per unit of money spent. This analysis generally excludes consideration of factors that are not measured ultimately in economic terms. Cost effectiveness compares alternative ways to achieve a specific set of results.

Cross-Over Studies - Studies comparing two or more treatments or interventions in which the subjects or patients, upon completion of the course of one treatment, are switched to another. In the case of two treatments, A and B, half the subjects are randomly allocated to receive these in the order A, B and half to receive them in the order B, A. A criticism of this design is that effects of the first treatment may carry over into the period when the second is given.

Cross-Sectional Studies - Studies in which the presence or absence of disease or other health-related variables are determined in each member of the study population or in a representative sample at one particular time. This contrasts with LONGITUDINAL STUDIES which are followed over a period of time.

Double-Blind Method - A method of studying a drug or procedure in which both the subjects and investigators are kept unaware of who is actually getting which specific treatment.

Empirical Research - The study, based on direct observation, use of statistical records, interviews, or experimental methods, of actual practices or the actual impact of practices or policies.

Evaluation Studies - Works consisting of studies determining the effectiveness or utility of processes, personnel, and equipment.

Genome-Wide Association Study - An analysis comparing the allele frequencies of all available (or a whole genome representative set of) polymorphic markers in unrelated patients with a specific symptom or disease condition, and those of healthy controls to identify markers associated with a specific disease or condition.

Intention to Treat Analysis - Strategy for the analysis of Randomized Controlled Trial that compares patients in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned.

Logistic Models - Statistical models which describe the relationship between a qualitative dependent variable (that is, one which can take only certain discrete values, such as the presence or absence of a disease) and an independent variable. A common application is in epidemiology for estimating an individual's risk (probability of a disease) as a function of a given risk factor.

Longitudinal Studies - Studies in which variables relating to an individual or group of individuals are assessed over a period of time.

Lost to Follow-Up - Study subjects in cohort studies whose outcomes are unknown e.g., because they could not or did not wish to attend follow-up visits.

Matched-Pair Analysis - A type of analysis in which subjects in a study group and a comparison group are made comparable with respect to extraneous factors by individually pairing study subjects with the comparison group subjects (e.g., age-matched controls).

Meta-Analysis - Works consisting of studies using a quantitative method of combining the results of independent studies (usually drawn from the published literature) and synthesizing summaries and conclusions which may be used to evaluate therapeutic effectiveness, plan new studies, etc. It is often an overview of clinical trials. It is usually called a meta-analysis by the author or sponsoring body and should be differentiated from reviews of literature.

Numbers Needed To Treat - Number of patients who need to be treated in order to prevent one additional bad outcome. It is the inverse of Absolute Risk Reduction.

Odds Ratio - The ratio of two odds. The exposure-odds ratio for case control data is the ratio of the odds in favor of exposure among cases to the odds in favor of exposure among noncases. The disease-odds ratio for a cohort or cross section is the ratio of the odds in favor of disease among the exposed to the odds in favor of disease among the unexposed. The prevalence-odds ratio refers to an odds ratio derived cross-sectionally from studies of prevalent cases.

Patient Selection - Criteria and standards used for the determination of the appropriateness of the inclusion of patients with specific conditions in proposed treatment plans and the criteria used for the inclusion of subjects in various clinical trials and other research protocols.

Predictive Value of Tests - In screening and diagnostic tests, the probability that a person with a positive test is a true positive (i.e., has the disease), is referred to as the predictive value of a positive test; whereas, the predictive value of a negative test is the probability that the person with a negative test does not have the disease. Predictive value is related to the sensitivity and specificity of the test.

Prospective Studies - Observation of a population for a sufficient number of persons over a sufficient number of years to generate incidence or mortality rates subsequent to the selection of the study group.

Qualitative Studies - Research that derives data from observation, interviews, or verbal interactions and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants.

Quantitative Studies - Quantitative research is research that uses numerical analysis.

Random Allocation - A process involving chance used in therapeutic trials or other research endeavor for allocating experimental subjects, human or animal, between treatment and control groups, or among treatment groups. It may also apply to experiments on inanimate objects.

Randomized Controlled Trial - Clinical trials that involve at least one test treatment and one control treatment, concurrent enrollment and follow-up of the test- and control-treated groups, and in which the treatments to be administered are selected by a random process, such as the use of a random-numbers table.

Reproducibility of Results - The statistical reproducibility of measurements (often in a clinical context), including the testing of instrumentation or techniques to obtain reproducible results. The concept includes reproducibility of physiological measurements, which may be used to develop rules to assess probability or prognosis, or response to a stimulus; reproducibility of occurrence of a condition; and reproducibility of experimental results.

Retrospective Studies - Studies used to test etiologic hypotheses in which inferences about an exposure to putative causal factors are derived from data relating to characteristics of persons under study or to events or experiences in their past. The essential feature is that some of the persons under study have the disease or outcome of interest and their characteristics are compared with those of unaffected persons.

Sample Size - The number of units (persons, animals, patients, specified circumstances, etc.) in a population to be studied. The sample size should be big enough to have a high likelihood of detecting a true difference between two groups.

Sensitivity and Specificity - Binary classification measures to assess test results. Sensitivity or recall rate is the proportion of true positives. Specificity is the probability of correctly determining the absence of a condition.

Single-Blind Method - A method in which either the observer(s) or the subject(s) is kept ignorant of the group to which the subjects are assigned.

Time Factors - Elements of limited time intervals, contributing to particular results or situations.

Source: NLM MeSH Database

- << Previous: How to Find Books

- Next: Types of Literature >>

- Last Updated: Aug 16, 2024 4:01 PM

- URL: https://research.library.gsu.edu/litrev

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Literature Review and Research Design

DOI link for Literature Review and Research Design

Get Citation

Designing a research project is possibly the most difficult task a dissertation writer faces. It is fraught with uncertainty: what is the best subject? What is the best method? For every answer found, there are often multiple subsequent questions, so it’s easy to get lost in theoretical debates and buried under a mountain of literature.

This book looks at literature review in the process of research design, and how to develop a research practice that will build skills in reading and writing about research literature—skills that remain valuable in both academic and professional careers. Literature review is approached as a process of engaging with the discourse of scholarly communities that will help graduate researchers refine, define, and express their own scholarly vision and voice. This orientation on research as an exploratory practice, rather than merely a series of predetermined steps in a systematic method, allows the researcher to deal with the uncertainties and changes that come with learning new ideas and new perspectives.

The focus on the practical elements of research design makes this book an invaluable resource for graduate students writing dissertations. Practicing research allows room for experiment, error, and learning, ultimately helping graduate researchers use the literature effectively to build a solid scholarly foundation for their dissertation research project.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part i | 2 pages, on research, chapter 1 | 15 pages, research philosophy, chapter 2 | 23 pages, research practice, part ii | 4 pages, reading literature, chapter 3 | 23 pages, chapter 4 | 26 pages, managing the literature, chapter 5 | 17 pages, deep reading, part iii | 4 pages, writing about literature, chapter 6 | 22 pages, writing with literature, chapter 7 | 19 pages, writing a literature review, chapter | 2 pages.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved October 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist

Debora fb leite, maria auxiliadora soares padilha, jose g cecatti.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2019 Jun 22; Accepted 2019 Sep 17; Issue date 2019.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.

A sophisticated literature review (LR) can result in a robust dissertation/thesis by scrutinizing the main problem examined by the academic study; anticipating research hypotheses, methods and results; and maintaining the interest of the audience in how the dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field. Unfortunately, little guidance is available on elaborating LRs, and writing an LR chapter is not a linear process. An LR translates students’ abilities in information literacy, the language domain, and critical writing. Students in postgraduate programs should be systematically trained in these skills. Therefore, this paper discusses the purposes of LRs in dissertations and theses. Second, the paper considers five steps for developing a review: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, writing the review and reflecting on the writing. Ultimately, this study proposes a twelve-item LR checklist. By clearly stating the desired achievements, this checklist allows Masters and Ph.D. students to continuously assess their own progress in elaborating an LR. Institutions aiming to strengthen students’ necessary skills in critical academic writing should also use this tool.

Keywords: Review, Checklist, Academic Performance, Critical Thinking, Learning

INTRODUCTION

Writing the literature review (LR) is often viewed as a difficult task that can be a point of writer’s block and procrastination ( 1 ) in postgraduate life. Disagreements on the definitions or classifications of LRs ( 2 ) may confuse students about their purpose and scope, as well as how to perform an LR. Interestingly, at many universities, the LR is still an important element in any academic work, despite the more recent trend of producing scientific articles rather than classical theses.

The LR is not an isolated section of the thesis/dissertation or a copy of the background section of a research proposal. It identifies the state-of-the-art knowledge in a particular field, clarifies information that is already known, elucidates implications of the problem being analyzed, links theory and practice ( 3 - 5 ), highlights gaps in the current literature, and places the dissertation/thesis within the research agenda of that field. Additionally, by writing the LR, postgraduate students will comprehend the structure of the subject and elaborate on their cognitive connections ( 3 ) while analyzing and synthesizing data with increasing maturity.

At the same time, the LR transforms the student and hints at the contents of other chapters for the reader. First, the LR explains the research question; second, it supports the hypothesis, objectives, and methods of the research project; and finally, it facilitates a description of the student’s interpretation of the results and his/her conclusions. For scholars, the LR is an introductory chapter ( 6 ). If it is well written, it demonstrates the student’s understanding of and maturity in a particular topic. A sound and sophisticated LR can indicate a robust dissertation/thesis.

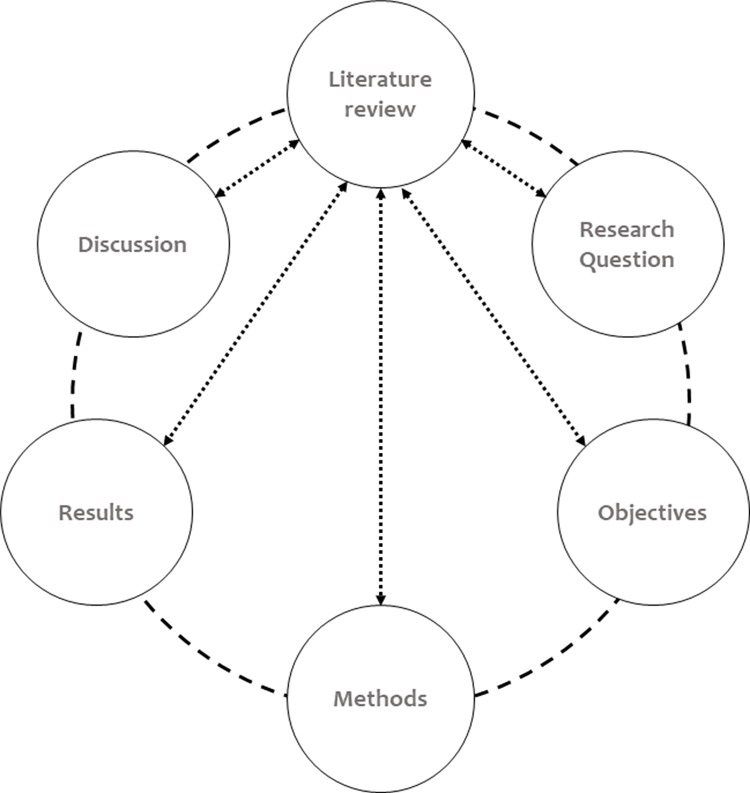

A consensus on the best method to elaborate a dissertation/thesis has not been achieved. The LR can be a distinct chapter or included in different sections; it can be part of the introduction chapter, part of each research topic, or part of each published paper ( 7 ). However, scholars view the LR as an integral part of the main body of an academic work because it is intrinsically connected to other sections ( Figure 1 ) and is frequently present. The structure of the LR depends on the conventions of a particular discipline, the rules of the department, and the student’s and supervisor’s areas of expertise, needs and interests.

Figure 1. The LR chapter is an elemental component of thesis and dissertations, and it is directly connected to other sections. By assessing the LR chapter, the reader might anticipate what to expect from the remaining sections of the academic text.

Interestingly, many postgraduate students choose to submit their LR to peer-reviewed journals. As LRs are critical evaluations of current knowledge, they are indeed publishable material, even in the form of narrative or systematic reviews. However, systematic reviews have specific patterns 1 ( 8 ) that may not entirely fit with the questions posed in the dissertation/thesis. Additionally, the scope of a systematic review may be too narrow, and the strict criteria for study inclusion may omit important information from the dissertation/thesis. Therefore, this essay discusses the definition of an LR is and methods to develop an LR in the context of an academic dissertation/thesis. Finally, we suggest a checklist to evaluate an LR.

WHAT IS A LITERATURE REVIEW IN A THESIS?

Conducting research and writing a dissertation/thesis translates rational thinking and enthusiasm ( 9 ). While a strong body of literature that instructs students on research methodology, data analysis and writing scientific papers exists, little guidance on performing LRs is available. The LR is a unique opportunity to assess and contrast various arguments and theories, not just summarize them. The research results should not be discussed within the LR, but the postgraduate student tends to write a comprehensive LR while reflecting on his or her own findings ( 10 ).

Many people believe that writing an LR is a lonely and linear process. Supervisors or the institutions assume that the Ph.D. student has mastered the relevant techniques and vocabulary associated with his/her subject and conducts a self-reflection about previously published findings. Indeed, while elaborating the LR, the student should aggregate diverse skills, which mainly rely on his/her own commitment to mastering them. Thus, less supervision should be required ( 11 ). However, the parameters described above might not currently be the case for many students ( 11 , 12 ), and the lack of formal and systematic training on writing LRs is an important concern ( 11 ).