Early Human Migration

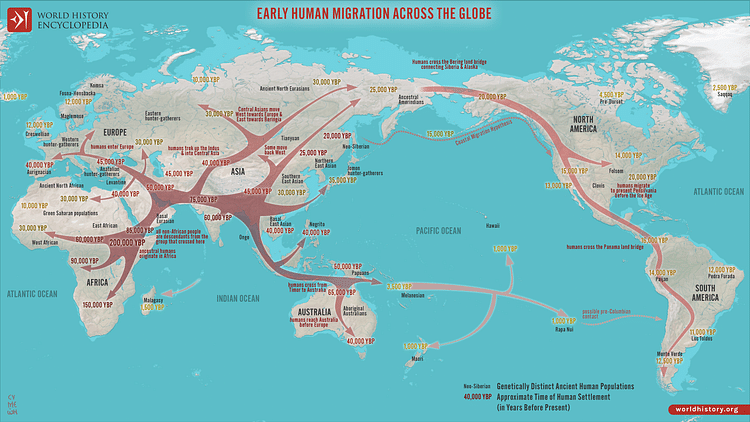

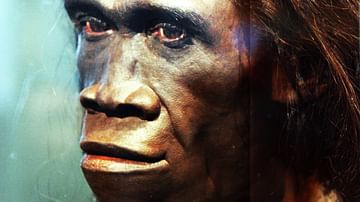

Disregarding the extremely inhospitable spots even the most stubborn of us have enough common sense to avoid, humans have managed to cover an extraordinary amount of territory on this earth. Go back 200,000 years, however, and Homo sapiens was only a newly budding species developing in Africa , while perceived ancestors such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis had already travelled beyond Africa to explore parts of Eurasia, and sister species like the Neanderthal and Denisovan would traipse around there way before we did, too. Meanwhile, the wake-up calls of Homo floresiensis , found in Indonesia, and Homo naledi from South Africa (which do not seem to fit with previous, more linear models) serve as excellent reminders that the story of human migrations across the prehistoric landscape is far from a simple one.

How, when, and why both fellow Homo species and our own Homo sapiens started moving all over the place is hotly debated. The story of early human migration covers such an immense time span and area that there cannot be but one explanation for all of these groups of adventurous hunter-gatherers going wandering around. Where for some groups a change in climate may have pushed them to seek more hospitable lands, others may have been looking for better food sources, avoiding hostile or competing neighbours, or may have simply been curious risk-takers wanting a change of scenery. This puzzle is further complicated by the fact that only a highly fragmentary fossil record exists (and we do not know exactly how fragmentary it is, or which bits are missing). Recently, the field of genetics has shot to the forefront by analysing ancient DNA, adding to the fossil, climatic, and geological data, so that hopefully we can attempt to piece together a story from all these titbits.

This story will keep changing, however - at least in the details but perhaps even amounting to considerable overhauls - as new bones are dug up, tools are found, and more DNA is studied with increasing accuracy. Here, a basic overview will be provided based on what we think we know right now, alongside a discussion of the possible motivations these many different early humans may have had to migrate away from their homelands, across the far reaches of our globe.

Early transcontinental adventurers

Already millions of years ago, middle and late Miocene hominoids – among which were the ancestors of our species of Homo as well as of the great apes – were present not just in Africa but also in parts of Eurasia. Our own branch developed in Africa, though; the Australopithecines , our supposed ancestors, lived in East and South Africa's grasslands. The earliest Homo to be securely found outside of Africa seems to be Homo erectus around 2 million years ago, and when interpreted in the broad sense (there is some dispute over which fossils should be included within the species) it is seen to have set the bar high, spanning an impressive geographical range indeed.

However, the very tricky to place species of Homo floresiensis (nicknamed 'hobbit'), found at Liang Bua in Indonesia, must be named, too; it may be descendant from a very early (before or not long after Erectus ) and still unknown migration from Africa. Clues are trickling in about migrations of people possibly predating Homo erectus , anyway. By now, five or six sites in Eurasia together span an suggested timeframe of roughly 2,6-2 million years ago, sporting tools made by as of yet unknown species; recent finds at Shangchen in the southern Chinese Loess Plateau, for instance, indicate hominin occupation there that dates back as far as 2,1 million years ago. Palaeoanthropologist John Hawks suspects that 'there were many movements and dispersals from Africa and back into Africa, starting much earlier than 2 million years ago and extending up to the most recent.' (Hawks, 12 July 2018). The main model followed today – that of Erectus being the first globetrotting humans spreading out from Africa across Eurasia – does not seem to account for all the evidence cropping up today. But, seeing that we do not have enough material yet to flesh out a more complex story, Homo erectus must still play a feature role in our story of early human migration.

Popping up in East Africa at sites such as Olduvai Gorge in the Turkana Basin in Kenya, from roughly 1,9 million years ago onwards, Homo erectus is also seen in South and North Africa. They are generally thought to have gone wandering out of Africa by 1,9-1,8 million years ago, travelling through the Middle East and the Caucasus and onwards towards Indonesia and China , which they reached around 1,7-1,6 million years ago. Erectus may even have braved the normally cold north of China in a period with somewhat milder temperatures, as early as roughly 800,000 years ago.

The follow-up crew

Erectus had set the trend for far-reaching early human migration, and their successors would push the boundaries further still. By around 700,000 years ago (and perhaps as early as 780,000 years ago), Homo heidelbergensis is thought to have developed from Homo erectus within Africa. There, different bands made territories within East, South, and North Africa their own. Of course, migration within Africa itself also occurred, in general.

From there on, a particularly energetic group of Homo heidelbergensis spread out all the way through western Eurasia, crossing the major mountain ranges of Europe and making it as far north as England and Germany. This is Ice Age Europe we are talking about, and these humans would have had to flow along with the often-changing climate; they were quite good at coping with the colder conditions of Europe and were able to survive on the southern edge of the subarctic zone, but naturally avoided the actual ice sheets. Evidence from Pakefield and Happisburgh in England, for instance, shows that early humans around 700,000 years ago were indeed able to make it this far north when the climate was more temperate, while they probably edged back into southern refuges during colder stages.

Homo Sapiens Spreads out

Meanwhile, what we call Homo sapiens gradually began to emerge, most likely from Heidelbergensis ancestors within the rich territories of Africa, in either Africa's southern or eastern reaches, by at least 200,000 years ago. Many sites have been found in both these regions that show that early bands of anatomically modern humans successfully lived there. However, they were not alone; the discovery in 2013 CE of Homo naledi in South Africa's Rising Star Cave, whose fossils were dated to between 236,000-335,000 years old, adds more players to the African stage. Already around c. 315,000 years ago, a species with some modern human features but also some archaic ones – possibly making them a precursor to Sapiens , or a related side-branch – lived out at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, Northern Africa, too. Genetic evidence furthermore seems to suggest that our modern human ancestors may well have had company from other ancient groups that were related to them in varying degrees. The story of hominin evolution is not one in which single species succeeded each other; it was rather a complex mosaic of different players, many of them likely interbreeding and/or overlapping in terms of timeframe.

From Africa, members of the branch that is related to us modern humans formed migrated away from their homelands and into the Near East, where Homo sapiens burials have been uncovered at the sites of Skhul and Qafzeh in Israel, dated to between 90,000 and a staggering 130,000 years old, respectively. Similarly, the site of Jebel Faya in the United Arab Emirates seems to show through the tools that were found there that Homo sapiens may have migrated here as early as 130,000 years ago, too. Even older migrations are not exactly unlikely, either, as fossils that appear to be Homo sapiens (although some alternatives have been suggested, too) found at Misliya Cave in Israel were recently found and dated to c. 180,000 years ago. Far from there being one, singular big migration of one species to far-flung areas – which does not really make sense if you think about it, anyway – there appear to have been multiple instances of adventurous people moving about.

A recent study has shown that some of these early adventurers made it all the way to the island of Sumatra in western Indonesia between 73,000 and 63,000 years ago; this ties in well with other evidence that hints at humans reaching inner Southeast Asia some time before 60,000 years ago, and then following the retreating glaciers up towards the north. There is even new evidence that places humans in the north of Australia by 65,000 years ago, seemingly also stemming from an early migration.

But which route did they take on this huge trek? Regarding possible ways out of Africa, Egypt is an option, but so is a journey through 'wet' corridors in the Sahara, through East Africa and into the Levant . Once out, we know through genetic research that in this Near Eastern setting, humans met Neanderthals and interbred with them (not for the first time, by the way: physical contact with them dates back to at least 100,000 years ago), after which an offshoot branched off and eventually migrated into Europe around 45,000 years ago.

Within Europe, modern humans probably dispersed rapidly, as hinted at by new evidence for their seemingly early arrival in southern Spain (for instance at Bajondillo Cave, Málaga) c. 43,000 years ago. In such a scenario of consistent and quick spread throughout Europe, the use of coastal corridors may have played a role. Homo sapiens also continued towards the east, though, probably all the way along the coastline, through India and into Southeast Asia, where they may have bumped into the possibly resident Denisovans and interbred with them (it is clear interbreeding happened somewhere, and the most likely location seems to be Southeast Asia).

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

All of this apparently happened at record speed; already by 53,000 years ago, descendants of that main wave out of Africa reached the north of Australia, the south taking until around 41,000 years ago. Reaching it was not straightforward, though. Although sea levels were about 100 meters lower than today, there was still a slightly inconvenient amount of water – a stretch of some 70 km – standing in between these early Homo sapiens in Asia and the landmass that included Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. Rather than surviving such an ambitious swim, they probably built boats or rafts to help them on this gutsy crossing.

Meanwhile, within Asia, a migration towards the north of East Asia could have begun around 40,000 years ago, paving the way to the Bering Land Bridge – a happy grassland steppe-covered side effect of the Ice Age, connecting Asia to the Americas. Humans are usually thought to have reached the Americas through this route, by around 15,000 years ago, expanding downwards along the coast or through an ice-free corridor in the interior, but this is far from a closed case. After this, there were some last strongholds that remained human-free for a long time still, such as Hawaii – reached by boat around 100 CE – and New Zealand, which held out until around 1000 CE.

Possible driving forces

The question of why these prehistoric people decided to leave and move somewhere else is a tough nut to crack, especially considering we are looking at a time that predates written sources. Migration is generally seen a result of push and pull factors, though, so that is a place to start. Push factors relate to the circumstances that can make someone's homeland an unpleasant enough place for them to ditch it entirely in favour of something new. With regard to these early human migrations, of course 'no jobs' or 'terrible political circumstances' do not apply; rather, think of stuff like the climate taking a turn for the worse and turning places into huge ovens or freezers where barely anything can live or grow, natural disasters, competition with hostile neighbouring groups, food and other resources running too low to support the amount of people within an area, or the more mobile type of food (herds of herbivores) migrating away.

Pull factors, on the other hand, involve the draw of new possibilities and rewards; basically, the more favourable side of the things mentioned in the 'push' section, such as greener lands with better climates and luscious amounts of food and resources. Of course, this is a bit of a simplification, and it will be hard to track down the exact combination of factors that led to each individual instance of early human migration.

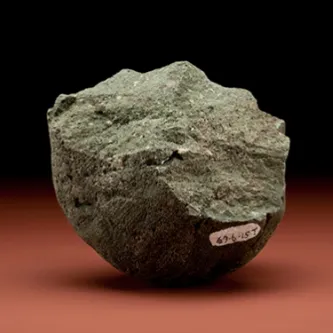

There are some prerequisites for successfully handling migration. It is stressful and dangerous – Homo erectus , for instance, most likely had no idea what they would find when they left Africa – and it challenges a group's resourcefulness and ability to adapt. If you move into a new environment, it helps to have adequate technology to help you tackle it; in this case, tools to successfully hunt and gather the resident animals and plants, or to protect yourself against colder areas via clothing or fire (the latter has been known by humans since probably at least 1,8 million years ago, but was not habitually used until probably between 500,000-400,000 years ago). Inventiveness and cooperation in securing new resources also help.

There was the slight problem of the Sahara standing between Homo sapiens and a possible way out, however. Other climate studies have shown, though, that there were 'wet' or 'green' phases during which more friendly corridors would have opened to form pathways across the Sahara, the timings of which seem to coincide with the major dispersal of humans leaving sub-Saharan Africa (identified wet periods are between roughly 50,000-c. 45,000 years ago and c. 120,000-c. 110,000 years ago). However, a recent study has shown that although the 'wet' phase holds up for Sapiens ' early migration into the Levant and Arabia between roughly 120,000-90,000 years ago, during the time of the main migration (around 55,000 years ago) the Horn of Africa was actually really dry, arid, and a bit colder. This may, then, have helped push the main wave out.

Another instance in which the impact of the climate on early human migration seems to become visible occurs even earlier. Around 870,000 years ago, temperatures dropped, and both North Africa and eastern Europe became a lot more arid than before. This may have caused large herbivores to migrate into southern European refuges, with early humans following hard on their tails. At the same time, the Po Valley in northern Italy first opened up and formed a pathway for possible migration into southern France and beyond. This ties in pretty well with Homo heidelbergensis making its way into Europe. Following herds of large herbivores would have been a good strategy in the challenging process of migration, anyway, and a 2016 CE study suggests Homo erectus may also have done this, while also sticking close to flint deposits and avoiding areas with loads of carnivores, at least early on in their dispersal.

Whatever the exact driving forces or the exact difficulties early humans ran into en route, as time passed adaptability reigned supreme and humans – starting with Homo erectus and culminating in Homo sapiens ' greedy dispersal - spread across the whole wide world.

Blind spots

There are obviously a lot of holes in this story, though, and it cannot hurt to explicitly name some of the blind spots we have to take into consideration at this point in time. As a whole, the dates mentioned above are only our best estimates based on our interpretation of the data we have gathered so far. Some areas in which the story can be fleshed out a lot more if we can get our hands on more evidence are found below.

The Denisovans, for instance, are known to us only through one finger bone and three molars found in a cave in Siberia, and through their DNA (their genome was sequenced in 2010 CE) which seems to imply they ranged from there all the way to Southeast Asia. It is moreover possible that they interbred with an unknown archaic human, which would obviously tell a story of its own. Fossils of these mysterious humans would be very welcome in trying to fill in the picture of their life and their movement. Another enigmatic species is Homo floresiensis ; exactly how and when did they get to the island of Flores (and did they somehow use boats at this very early point in time)? Who were their ancestors? More evidence is required to seal the deal on this.

More evidence is clearly needed before this can overwrite the current story regarding the Americas, but it forms a good example of what could happen to our current image of early human migration as new discoveries are made. We certainly cannot paint a complete and finished picture yet.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- A find in Australia hints at very early human exit from Africa Accessed 29 Aug 2017.

- John Hawks - Reinforcing the antiquity of hominins in China (12 July 2018) Accessed 21 Sep 2018.

- John Hawks - Three new discoveries in a month rock our African origins (7 June 2017) Accessed 19 Mar 2020.

- Adler, L. L. and U. W. Gielen (eds.). Migration: Immigration and Emigration in International Perspective. Praeger, Westport, 2003

- Argue, D. e.a. "Migration in World History." Journal of Human Evolution , 2017, pp. 1-27.

- Armitage, Simon J. e.a. "The Southern Route “Out of Africaâ€: Evidence for an Early Expansion of Modern Humans into Arabia." Science , Vol. 331, Issue 6016, 28 January 2011, pp. 453-456.

- Carotenuto, F. e.a. "Venturing out safely: The biogeography of Homo erectus dispersal out of Africa." Journal of Human Evolution , Volume 95, June 2016, pp. 1-12.

- Carto, Shannon L. e.a. "Out of Africa and into an ice age: on the role of global climate change in the late Pleistocene migration of early modern humans out of Africa." Journal of Human Evolution , Volume 56, Issue 2, February 2009, pp. 139–151.

- Castañeda, Isla S. e.a. "Wet phases in the Sahara/Sahel region and human migration patterns in North Africa." PNAS , vol. 106, no. 48, December 2009, pp. 20159–20163.

- Cortés-Sánchez, M. e.a. "An early Aurignacian arrival in southwestern Europe." Nature Ecology & Evolution , Vol 3 (February 2019), pp. 207-212.

- Coulthard, Tom J. e.a. "Were Rivers Flowing across the Sahara During the Last Interglacial? Implications for Human Migration through Africa." PLOS ONE , 8 (9): e74834, September 2013.

- Drake, Nick A. e.a. "Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert." PNAS , vol. 108, no. 2, January 2011, pp. 458–462.

- Fagundes, Nelson J.R. e.a. "Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas." AJHG , Volume 82, Issue 3, 3 March 2008, pp. 583-592.

- Goebel, T., M. R. Waters and D. H. O'Rourke. "The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas." Science , Vol. 319, Issue 5869, 14 March 2008, pp. 1497-1502.

- Gowlett, J., and R.W. Wrangham. "Earliest fire in Africa: towards the convergence of archaeological evidence and the cooking hypothesis." Azania Arch. Res. Africa , 48, 2013, pp. 5-30.

- Groucutt, Huw S. e.a. "Rethinking the Dispersal of Homo Sapiens out of Africa." Evolutionary Anthropology , 24, 2015, pp. 149-164.

- Henke, Winfried, and Ian Tattersall (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol III. Springer, 2015

- Holen, S. R. e.a. "A 130,000-year-old archaeological site in southern California, USA." Nature , 544, 27 April 2017, pp. 479–48.

- Kitchen, A., M. M. Miyamoto and C. J. Mulligan. "A Three-Stage Colonization Model for the Peopling of the Americas." PLOS ONE , Volume 3, Issue 2, February 2008.

- Macaulay, V. e.a. "Single, Rapid Coastal Settlement of Asia Revealed by Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genomes." Science , Vol. 308, Issue 5724, 13 May 2005, pp. 1034-1036.

- Mallick, S. e.a. "The Simons Genome Diversity Project: 300 genomes from 142 diverse populations." Nature , 538, 13 October 2016, pp. 201–206.

- Manning, Patrick. Migration in World History. Routledge, New York & London, 2005

- Muttoni, G., G. Scardia and D. V. Kent. "Human migration into Europe during the late Early Pleistocene climate transition." Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology , Volume 296, Issues 1–2, 1 October 2010, pp. 79–93.

- Osborne, Anne H. e.a. "A humid corridor across the Sahara for the migration of early modern humans out of Africa 120,000 years ago." PNAS , vol. 105, no. 43, October 2008, pp. 16444–16447.

- Pagani, L. e.a. "Genomic analyses inform on migration events during the peopling of Eurasia." Nature , 538, 13 October 2016, pp. 238–242.

- Pagani, L. e.a. "Tracing the Route of Modern Humans out of Africa by Using 225 Human Genome Sequences from Ethiopians and Egyptians." The American Journal of Human Genetics , 96, 4 June 2015, pp. 986–991.

- Parfitt, Simon A. e.a. "Early Pleistocene human occupation at the edge of the boreal zone in northwest Europe." Nature , 466, 08 July 2010, pp. 229–233.

- Posth, C. e.a. "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe." Current Biology , Volume 26, Issue 6, 21 March 2016, pp. 827–833.

- Reich, D. e.a. "Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania." Am J Hum Genet. , 89(4), 7 October 2011, pp. 516–528.

- Shimelmitz, R. e.a. "Fire at will’: the emergence of habitual fire use 350,000 years ago." J. Hum. Evol. , 77, 2014, pp. 196–203.

- Stringer, C. & J. Galway-Witham. "When did modern humans leave Africa?." Science , Vol. 359, Issue 6374 (26 jan 2018), pp. 389-390.

- Stringer, Chris. Lone Survivors. How we came to be the only humans on earth. St. Martin's Griffin, 2013.

- Su, B. e.a. "Y-Chromosome Evidence for a Northward Migration of Modern Humans into Eastern Asia during the Last Ice Age." Am. J. Hum. Genet. , Volume 65, Issue 6, December 1999, pp. 1718–1724.

- Tierney, J. E., P. B. deMenocal & P. D. Zander. "A climatic context for the out-of-Africa migration." Geology , 2 October 2017, pp. Online access.

- Vernot, B. and J. M. Akey. "Complex History of Admixture between Modern Humans and Neandertals." Am J Hum Genet. , 96(3), 5 March 2015, pp. 448–453.

- Westaway, K. E. e.a. "An early modern human presence in Sumatra 73,000–63,000 years ago." Nature , 548 (17 August 2017), pp. 322–325.

- Zhong, H. e.a. "Global distribution of Y-chromosome haplogroup C reveals the prehistoric migration routes of African exodus and early settlement in East Asia." Journal of Human Genetics , 55, 2010, pp. 428–435.

- Zhu, Z. e.a. "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago." Nature , Vol 559 (26 July 2018), pp. 608-611.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

Homo Heidelbergensis

Homo Floresiensis

Homo Naledi

Homo Erectus

The Neanderthal-Sapiens Connection

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Groeneveld, E. (2017, May 15). Early Human Migration . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1070/early-human-migration/

Chicago Style

Groeneveld, Emma. " Early Human Migration ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified May 15, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1070/early-human-migration/.

Groeneveld, Emma. " Early Human Migration ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 15 May 2017. Web. 06 Jul 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Emma Groeneveld , published on 15 May 2017. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Background and beginnings in the Miocene

- The anatomy of bipedalism

- The fossil evidence

- Theories of bipedalism

- Hominin habitats

- Refinements in hand structure

- Increasing brain size

- Refinements in tool design

- Reduction in tooth size

- The emergence of Homo sapiens

- Speech and symbolic intelligence

- Learning from the apes

What is a human being?

When did humans evolve, are neanderthals classified as humans.

human evolution

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- NeoK12 - Educational Videos and Games for School Kids - Human Evolution

- Social Science LibreTexts - Human Evolution

- The University of Waikato - School of Science and Engineering - Human Evolution

- Your Genome - Evolution of modern humans

- Natural History Museum - Human evolution

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History - What does it mean to be human?

- human origins - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- human origins - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Humans are culture-bearing primates classified in the genus Homo , especially the species Homo sapiens . They are anatomically similar and related to the great apes ( orangutans , chimpanzees , bonobos , and gorillas ) but are distinguished by a more highly developed brain that allows for the capacity for articulate speech and abstract reasoning. Humans display a marked erectness of body carriage that frees the hands for use as manipulative members.

The answer to this question is challenging, since paleontologists have only partial information on what happened when. So far, scientists have been unable to detect the sudden “moment” of evolution for any species, but they are able to infer evolutionary signposts that help to frame our understanding of the emergence of humans. Strong evidence supports the branching of the human lineage from the one that produced great apes (orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas) in Africa sometime between 6 and 7 million years ago. Evidence of toolmaking dates to about 3.3 million years ago in Kenya . However, the age of the oldest remains of the genus Homo is younger than this technological milestone, dating to some 2.8–2.75 million years ago in Ethiopia . The oldest known remains of Homo sapiens —a collection of skull fragments, a complete jawbone, and stone tools—date to about 315,000 years ago.

Did humans evolve from apes?

No. Humans are one type of several living species of great apes. Humans evolved alongside orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas. All of these share a common ancestor before about 7 million years ago.

Yes. Neanderthals ( Homo neanderthalensis ) were archaic humans who emerged at least 200,000 years ago and died out perhaps between 35,000 and 24,000 years ago. They manufactured and used tools (including blades, awls, and sharpening instruments), developed a spoken language , and developed a rich culture that involved hearth construction, traditional medicine , and the burial of their dead. Neanderthals also created art ; evidence shows that some painted with naturally occurring pigments . In the end, Neanderthals were likely replaced by modern humans ( H. sapiens ), but not before some members of these species bred with one another where their ranges overlapped.

Trusted Britannica articles, summarized using artificial intelligence, to provide a quicker and simpler reading experience. This is a beta feature. Please verify important information in our full article.

This summary was created from our Britannica article using AI. Please verify important information in our full article.

human evolution , the process by which human beings developed on Earth from now-extinct primates . Viewed zoologically, we humans are Homo sapiens , a culture -bearing upright-walking species that lives on the ground and very likely first evolved in Africa about 315,000 years ago. We are now the only living members of what many zoologists refer to as the human tribe, Hominini , but there is abundant fossil evidence to indicate that we were preceded for millions of years by other hominins, such as Ardipithecus , Australopithecus , and other species of Homo , and that our species also lived for a time contemporaneously with at least one other member of our genus , H. neanderthalensis (the Neanderthals ). In addition, we and our predecessors have always shared Earth with other apelike primates, from the modern-day gorilla to the long-extinct Dryopithecus . That we and the extinct hominins are somehow related and that we and the apes , both living and extinct , are also somehow related is accepted by anthropologists and biologists everywhere. Yet the exact nature of our evolutionary relationships has been the subject of debate and investigation since the great British naturalist Charles Darwin published his monumental books On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871). Darwin never claimed, as some of his Victorian contemporaries insisted he had, that “man was descended from the apes ,” and modern scientists would view such a statement as a useless simplification—just as they would dismiss any popular notions that a certain extinct species is the “ missing link ” between humans and the apes. There is theoretically, however, a common ancestor that existed millions of years ago. This ancestral species does not constitute a “missing link” along a lineage but rather a node for divergence into separate lineages. This ancient primate has not been identified and may never be known with certainty, because fossil relationships are unclear even within the human lineage, which is more recent. In fact, the human “family tree” may be better described as a “family bush,” within which it is impossible to connect a full chronological series of species, leading to Homo sapiens , that experts can agree upon.

(Read T. H. Huxley’s 1875 Britannica essay on evolution & biology.)

The primary resource for detailing the path of human evolution will always be fossil specimens. Certainly, the trove of fossils from Africa and Eurasia indicates that, unlike today, more than one species of our family has lived at the same time for most of human history. The nature of specific fossil specimens and species can be accurately described, as can the location where they were found and the period of time when they lived; but questions of how species lived and why they might have either died out or evolved into other species can only be addressed by formulating scenarios, albeit scientifically informed ones. These scenarios are based on contextual information gleaned from localities where the fossils were collected. In devising such scenarios and filling in the human family bush, researchers must consult a large and diverse array of fossils, and they must also employ refined excavation methods and records, geochemical dating techniques, and data from other specialized fields such as genetics , ecology and paleoecology, and ethology ( animal behaviour )—in short, all the tools of the multidisciplinary science of paleoanthropology .

This article is a discussion of the broad career of the human tribe from its probable beginnings millions of years ago in the Miocene Epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago [mya]) to the development of tool -based and symbolically structured modern human culture only tens of thousands of years ago, during the geologically recent Pleistocene Epoch (about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). Particular attention is paid to the fossil evidence for this history and to the principal models of evolution that have gained the most credence in the scientific community . See the article evolution for a full explanation of evolutionary theory, including its main proponents both before and after Darwin, its arousal of both resistance and acceptance in society, and the scientific tools used to investigate the theory and prove its validity.

Human Evolution

Six million years of human evolution.

Human evolution is the lengthy process of change by which people originated from apelike ancestors. Scientific evidence shows that the physical and behavioral traits shared by all people originated from apelike ancestors and evolved over a period of approximately six million years.

Paleoanthropology is the scientific study of human evolution which investigates the origin of the universal and defining traits of our species. The field involves an understanding of the similarities and differences between humans and other species in their genes, body form, physiology, and behavior. Paleoanthropologists search for the roots of human physical traits and behavior. They seek to discover how evolution has shaped the potentials, tendencies, and limitations of all people.

What Can Human Fossils Tell Us?

Early human fossils and archeological remains offer the most important clues about this ancient past. These remains include bones, tools and any other evidence (such as footprints, evidence of hearths , or butchery marks on animal bones) left by earlier people. Usually, the remains were buried and preserved naturally. They are then found either on the surface (exposed by rain, rivers, and wind erosion) or by digging in the ground. By studying fossilized bones, scientists learn about the physical appearance of earlier humans and how it changed. Bone size, shape, and markings left by muscles tell us how those predecessors moved around, held tools, and how the size of their brains changed over a long time.

Archeological evidence refers to the things earlier people made and the places where scientists find them. By studying this type of evidence, archeologists can understand how early humans made and used tools and lived in their environments.

Humans and Our Evolutionary Relatives

Humans are primates . Physical and genetic similarities show that the modern human species, Homo sapiens, has a very close relationship to another group of primate species, the apes. Modern humans and the great apes (large apes) of Africa – chimpanzees (including bonobos, or so-called “pygmy chimpanzees”) and gorillas – share a common ancestor that lived between 8 and 6 million years ago.

Humans first evolved in Africa, and much of human evolution occurred on that continent. The fossils of early humans who lived between 6 and 2 million years ago come entirely from Africa. Early humans first migrated out of Africa into Asia probably between 2 million and 1.8 million years ago. They entered Europe somewhat later, between 1.5 million and 1 million years. Species of modern humans populated many parts of the world much later. For instance, people first came to Australia probably within the past 60,000 years and to the Americas within the past 15,000 years or so.

Most scientists currently recognize some 15 to 20 different species of early humans. Scientists do not all agree, however, about how these species are related or which ones simply died out. Many early human species – certainly the majority of them – left no living descendants. Scientists also debate over how to identify and classify particular species of early humans, and about what factors influenced the evolution and extinction of each species.

Human Characteristics

One of the earliest defining human traits, bipedalism – the ability to walk on two legs – evolved over 4 million years ago. Other important human characteristics – such as a large and complex brain, the ability to make and use tools, and the capacity for language – developed more recently. Many advanced traits -- including complex symbolic expression, art , and elaborate cultural diversity – emerged mainly during the past 100,000 years. The beginnings of agriculture and the rise of the first civilizations occurred within the past 12,000 years.

Smithsonian Research Into Human Evolution

The Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program explores the universal human story at its broadest time scale. Smithsonian anthropologists research many aspects of human evolution around the globe, investigating fundamental questions about our evolutionary past, including the roots of human adaptability.

For example, Paleoanthropologist Dr. Rick Potts – who directs the Human Origins Program – co-directs ongoing research projects in southern and western Kenya and southern and northern China that compare evidence of early human behavior and environments from eastern Africa to eastern Asia. Rick’s work helps us understand the environmental changes that occurred during the times that many of the fundamental characteristics that make us human - such as making tools and large brains – evolved, and that our ancestors were often able to persist through dramatic climate changes. Rick describes his work in the video Survivors of a Changing Environment .

Dr. Briana Pobiner is a Prehistoric Archaeologist whose research centers on the evolution of human diet (with a focus on meat-eating), but has included topics as diverse as cannibalism in the Cook Islands and chimpanzee carnivory. Her research has helped us understand that at the onset of human carnivory over 2.5 million years ago some of the meat our ancestors ate was scavenged from large carnivores, but by 1.5 million years ago they were getting access to some of the prime, juicy parts of large animal carcasses. She uses techniques similar to modern day forensics for her detective work on early human diets.

Paleoanthropologist Dr. Matt Tocheri conducts research into the evolutionary history and functional morphology of the human and great ape family, the Hominidae. His work on the wrist of Homo floresiensis , the so-called “hobbits” of human evolution discovered in Indonesia, received considerable attention worldwide after it was published in 2007 in the journal Science. He now co-directs research at Liang Bua on the island of Flores in Indonesia, the site where Homo floresiensis was first discovered.

Geologist Dr. Kay Behrensmeyer has been a long-time collaborator with Rick Potts’ human evolution research at the site of Olorgesailie in southern Kenya. Kay’s role with the research there is to help understand the environments of the sites at which evidence for early humans – in the form of stone tools as well as fossils of the early humans themselves – have been found, by looking at the sediments of the geological layers in which the artifacts and fossils have been excavated.

Related Resources

- Smithsonian Institution

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Host an Event

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Unit 6: Early Humans

About this unit.

Humans are unusual. We walk upright and build cities. We travel from continent to continent in hours. We communicate across the globe in an instant. We alone can build bombs and invent medicines. Why can we do all these things that other creatures can’t? What makes us so different from other species? Investigating how early humans evolved and lived helps us answer these questions. Most people give our big brains all the credit, but that’s only part of the story. To more fully understand our success as a species, we need to look closely at our ancestors and the world they lived in. You’ll learn how foraging humans prospered and formed communities, and you’ll uncover the uniquely human ability to preserve, share, and build upon each other’s ideas to learn collectively.

How Our Ancestors Evolved | 6.0

- ACTIVITY: Vocab Tracking (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Unit 6 Overview (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: Early Ancestors (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: Threshold Card — Threshold 6 Collective Learning (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Threshold 6 — Humans and Collective Learning (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Human Evolution (Opens a modal)

- READ: Lucy and the Leakeys (Opens a modal)

- READ: Jane Goodall (Opens a modal)

- READ: Gallery — Human Ancestors (Opens a modal)

- Quiz: How Our Ancestors Evolved 14 questions Practice

Ways of Knowing: Early Humans | 6.1

- ACTIVITY: DQ Notebook 6.1 (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Intro to Anthropology (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Intro to Archaeology (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: What Do You Know? What Do You Ask? (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: Historos Cave (Opens a modal)

- Quiz: Early Humans 12 questions Practice

Collective Learning | 6.2

- READ: Collective Learning (Part 1) (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Why Human Evolution Matters (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: The Common Man (H2) (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Early Evidence of Collective Learning (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: Claim Testing – Collective Learning (Opens a modal)

- READ: Gallery — What Makes Humans Different? (Opens a modal)

- Quiz: Collective Learning 12 questions Practice

How Did the First Humans Live? | 6.3

- ACTIVITY: DQ Notebook 6.3 (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: How Did The First Humans Live? (Opens a modal)

- READ: Foraging (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: From Foraging to Food Shopping (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: Hunter Gatherer Menu (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Why Human Ancestry Matters (Opens a modal)

- ACTIVITY: Human Migration Patterns (Opens a modal)

- READ: Ales Hrdlicka - Graphic Biography (Opens a modal)

- READ: George McJunkin - Graphic Biography (Opens a modal)

- READ: Gallery — How Did the First Humans Live? (Opens a modal)

- Quiz: How Did the First Humans Live? 15 questions Practice

Other Materials

- WATCH: Making Stone Tools (Opens a modal)

- WATCH: Genealogy and Human Ancestry (Opens a modal)

- Glossary: Early Humans (Opens a modal)

- Guide, Slides, and Text Reader (Opens a modal)

- Video Transcripts (Opens a modal)

- Vocab Guide (Opens a modal)

- Google Docs (Opens a modal)

- Privacy and Cookie Policy

- Ancient History

- Our Free Lesson Plans and Classroom Activities

- Archaeology

- Early Humans

- Mesopotamia

- Free Use Clipart

- American History

- Native Americans

- New World Explorers

- 13 Colonies

- Revolutionary War

- Creating a New Nation and US Constitution

- Western Expansion

- The Civil War

- Industrial Revolution

- Roaring 20s

- Great Depression

- World History

- African Kingdoms

- Middle Ages

- Renaissance Reformation and More

- Age of Exploration

- Holidays Around the World

- FAQ, About Us, Contact

- Show More Show Less

The Life and Times of Early Man

Very early humans probably ate mostly plants, fruit, nuts and roots that they found. Any meat they got was by scavenging after other animals. Early humans did not have strong claws to help them him fight. They could not outrun saber-toothed tigers or cave lions. Early humans had to get smart to survive. They had to use reason and invention.

Introduction - Four Important Definitions You'll Need

Back in time, 3 million years ago

The Stone Age

Handy Man - Stone Age (Stone Tools)

Upright Man - Made and controlled fire & learned to cook food

Hunter/Gatherer

Neanderthals

Cro-Magnon Man

Cave Paintings

What does it take for a group of people to become a civilization?

Investigate Real Life Artifacts

Take the Quiz! Interactive quiz on Early Humans

Timeline Interactive

For Teachers

Lesson Plans about Early Humans

Early Humans - Activities and Projects for the Classroom - Activities for cave art, eras, hunts, fire, tools, and more

We're published!

Mr. Donn and Maxie's Ancient History PowerPoints Series Written by Lin & Don Donn, illustrated by Phillip Martin, Published by Good Year Books

Mr. Donn and Maxie's Always Something You Can Use Series Written by Lin & Don Donn, Published by Good Year Books

Our books and educational materials are available through our publisher , and through Amazon online & Borders (Barnes and Noble) in store

Explore Early Humans

For Kids: Free Early Humans Interactive Games Online for Kids

Early Humans Online Interactive Quiz (with questions and answers)

For Teachers: Early Humans Free Use Lesson Plans

Free Use Presentations in PowerPoint format about Early Man

Return to Index: Early Humans for Kids

Early Homo Sapiens

Biological anthropologists place the initial emergence of our species, Homo sapiens , around 300,000 years ago. In this unit, students will learn about the evolution of our species and read about some of the many questions biological anthropologists are still asking about our ancestors.

New Discovery Expands the Hobbit Family Tree

Will Asia Rewrite Human History?

Celebrity Status Almost Ruined Ancient DNA Research

Gene Therapy’s Promise Meets Nigeria’s Sickle Cell Reality

Decoding Diversity and Power at Machu Picchu

The Hidden Ancestry Extracted From an Ancient Pendant

Navigating the Ethics of Ancient DNA Research

Did Humanity Really Arise in One Place?

- Lay out the evidence scientists use to piece together the story of human evolution.

- Explain different hypotheses about why Homo sapiens persisted until today and other species in the Homo genus went extinct.

- Explore what it means to be human and what distinguishes anatomically modern humans from other related and ancestral species.

Facchini, Fiorenzo. 2006. “Culture, Speciation, and the Genus Homo in Early Humans.” Human Evolution 21: 51–57.

Shea, John J. 2011. “ Homo sapiens Is as Homo sapiens Was: Behavioral Variability Versus ‘Behavioral Modernity’ in Paleolithic Archaeology.” Current Anthropology 52 (1): 1–35.

Tryon, Christian, and Shara Bailey. 2013.“Testing Models of Modern Human Origins With Archaeology and Anatomy.” Nature Education Knowledge 4 (3): 4.

- What kinds of morphological features differentiate early Homo sapiens from other Homo species?

- How does the 2020 SAPIENS article by Sara Toth Stub challenge prior theories about Homo sapiens ’ migration out of the African continent?

- Have students watch this TED Talk by Zeresenay Alemseged “ The Search for Humanity’s Roots ” and generate a class discussion on why societies invest so much in pursuit of illuminating humanity’s origins.

- In class or through individual work, have students carefully explore the Smithsonian Institution’s interactive on the Human Family Tree .

Article: SAPIENS’ “ How Eating Rat Stew Serves Hobbit Research ”

Article: SAPIENS’ “ Were Neanderthals More Than Cousins to Homo Sapiens ? ”

TED Talk: Svante Pääbo’s “ DNA Clues to Our Inner Neanderthal ”

TED Talk: Robert Sapolsky’s “ The Uniqueness of Humans ”

Eshe Lewis (2020)

Human Genetic Variation

Y ou may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

I n short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on SAPIENS.

A ccompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

We’re glad you enjoyed the article! Want to republish it?

This article is currently copyrighted to SAPIENS and the author. But, we love to spread anthropology around the internet and beyond. Please send your republication request via email to editor•sapiens.org.

Accompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Evolution theory explains the change in the human species’ characteristics over generations based on archeological evidence. The cultural behaviors of early hominids are altered with the changes in physical features. Ardipithecus ramidus, Australopithecines, Homo habilis, Homo erectus, and Homo Neanderthal are stages of human evolution with distinct physical appearances and behavior. Earlier, man’s biological and cultural characteristics evolved gradually in response to different environmental factors.

Ardipithecus ramidus is the initial genus of Hominidae that possesses ape-like biological and cultural features. Ardipithecus had rigid pelvis and hind and front limbs implying full bipedal characteristics (Bala, 2020). Ardipithecus displayed a small endocrinal brain capacity (300 to 350 cm3) relative to the body size. These primates were most likely omnivores, suggesting they were hunters and gatherers with a generalized diet of plants, fruits, and meat (Haviland et al., 2015). Similar to other early hominids, Ardipithecus lived in groups in the woods, signified by the tree-climbing skills displayed by their strong limbs.

Australopithecines or Australopithecus had close physical and cultural characteristics with Ardipithecus ramidus. Australopithecus had ape-like physical appearance but bipedal features and small cerebrums (Haviland et al., 2015). At the same time, Australopithecines had smaller canine teeth and massive check jaws, suggesting they were omnivores (Anderson & Tornberg, 2019). The pelvis, limbs, jaws, and teeth of Australopithecus closely resemble humans, but their brain capacity is relatively small (430 cubic centimeters). Australopithecus used tools similar to modern apes, such as sticks and twigs that could effortlessly be redesigned.

Homo habilis was a more advanced human genus than the primitive Australopithecus, exhibited by physical and cultural characteristics. According to Galway-Witham (2019), Homo habilis had a relatively high cranial capacity (500 to 800 cubic centimeters). The foot and hand bones were more human-like, with the ability to manipulate objects hence the name “handy man” (Bala, 2020). The molars and premolars of Homo habilis were comparatively smaller than Ardipithecus and Australopithecus . Homo habilis predominantly lived in grassland environments and could make stone tools such as choppers, scrapers, and flakes, often called Oldowan stone tools.

Homo erectus, identified as “upright man,” exhibited close biological and cultural characteristics to humans. Their body size and shape were identical to humans, although their hips were much broader and more muscular. They had shorter arms with longer legs and could stand upright (Anderson & Tornberg, 2019). Homo erectus skull and teeth were smaller than earlier hominids, although omnivores. The upright man mastered the use of fire and stone to make tools such as knives and scrappers (Galway-Witham, 2019). Homo erectus had a larger brain size than Homo habilis (about 950 cubic centimeters) and could use perishable wood materials and grass to make ropes and strings. Homo erectus were active hunters that did not grow crops but could feed on wild fruits.

Homo Neanderthal is the most recent species of evolution that had analogous features with humans. Neanderthals had an extended lower skull with an enormous nose and a protruded facial shape. With large bones, they were stronger and more muscular than modern humans (Galway-Witham, 2019). Neanderthals made complex tools from stones that they used in scavenging plantations and hunting. They had a significantly higher brain volume of 11,000 low temperatures by using fire to cook, warm their bodies, and protect themselves from wild animals. (Haviland et al., 2015). Culturally, Homo Neanderthals buried the dead and knew how to use fire to make advanced stone technology.

Andersson, C., & Törnberg, P. (2019). Toward a macroevolutionary theory of human evolution: The social protocell. Biological Theory , 14 (2), 86-102.

Bala, S. (2020). Human evolution: insignificant ape to an intelligent designer. International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences , 7 (12), 6-14. Web.

Galway‐Witham, J., Cole, J., & Stringer, C. (2019). Aspects of human physical and behavioral evolution during the last 1 million years . Journal of Quaternary Science , 34 (6), 355-378.

Haviland, W. A., Prins, H. E., & McBride, B. (2015). The essence of anthropology . Cengage Learning.

- Biological Anthropology: Hominid Evolution

- Archaeology of Ancient People

- Evolution Process and the Study of Hominids

- Aggression in Nonhuman Primates and Human Evolution

- History: Evolution of Humans

- Neanderthals: Debates Regarding the History of Neanderthals

- Aspects of Evolution and Creationism

- Medical Breakthrough: The Bionic Eye

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, February 18). Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hominids-and-stages-of-human-evolution/

"Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution." IvyPanda , 18 Feb. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/hominids-and-stages-of-human-evolution/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution'. 18 February.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution." February 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hominids-and-stages-of-human-evolution/.

1. IvyPanda . "Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution." February 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hominids-and-stages-of-human-evolution/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Hominids and Stages of Human Evolution." February 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hominids-and-stages-of-human-evolution/.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Today

Largest Compilation of Structured Essays and Exams

Early Human Essay for Children | Early Man Lifestyle | History

December 2, 2017 by Study Mentor Leave a Comment

Man has developed from prehistoric ages from an ape like creature to what he is now. From fours he started walking on twos. From stooping on the ground he started to stand up on his legs. He learnt to walk run hunt and cook.

Man’s evolution came about in certain phases. It wasn’t done in a jiffy. But it came about in a very slow and gradual phase.

Before, man used to live on trees like apes. They had a huge head and a smaller brain. His senses weren’t that developed that time. His only means of survive was to eat the wild berries and fruits that grew on trees. He was a prey that time and not a predator, since he did not know any hunting skills. He was preyed on like other monkeys and apes. His body was full of hair and he had a tail also.

As time passed man came down from the trees to the land. He started residing in caves and niches in mountains. The hair quantity in his body reduced.

Then man developed tools. This brought a major change in his life. He learnt the art of hunting. He learnt how to make sharp object by rubbing two objects with each other. With tools now he could build temporary sheds and hunt animals at close proximity.

Another change that came with tools was that he started walking on twos instead of all fours. Yes! Man started using his lower limbs. But his walk wasn’t this upright and straight as it is now. It was more like how gorillas look when they walk on their feet; slightly humped in front and the movement is from side to side.

While rubbing two stones to sharpen them man made another accidental discovery that is fire. Till then fire was a matter of mystery, something fearful, and something unknown. Something, that cannot be under control. It was an act of nature. But when man learnt this new trick he could produce fire at his will by rubbing two stones or two twigs together. He became the master of fire.

The size of his brain increased considerably. He stood more upright. With fire at control there came many advantages. He could now have cooked food (before man used to devour raw flesh) hence it enhanced his taste buds. He can now light up dark caves and stay up late in the night. Also now they have this instrument to protect themselves from wild animals. They can also keep themselves warm in winters. From a herbivore he became an omnivore.

By this time he had learnt to tame animals. He started taming animals of domestic behavior. Man started living in groups. From a nomadic nature he started having a family. From a collection of different families it soon turned into a prehistoric village.

Man shifted from the caves to the open land. He built himself huts. Separate huts for separate families. Man learnt that the soil near the river is most fertile and there is also an easy availability of water. Villages started coming up along the banks of the water sources.

Man started producing food instead of just eating the wild fruits. The very first grains to be cultivated are still unknown because at that time trees also hadn’t undergone much evolution and there were a lot more different species of trees. So the main diet of man comprised of wild fruits, berries, meat, milk from the animals he domesticated and the grains that he grew.

He started practicing shifting agriculture that is suppose they settled in an area and cleared the forest cover there and started their agriculture there. But after some years the soil will lose its fertility, then again the people will shift to a new area, make a new clearing and start cultivating again, and leave the earlier patch to regenerate itself.

The third breakthrough came with the discovery of wheels. Man saw wooden logs of trees to roll down easily from a hill top. This gave him the idea of making wheels. He tied his domesticated animals to the wheels and used them to pull the wheels. This gave him the basic idea of making a cart. Early carts were very different from us though.

Nothing much is known about the language of early man at those times. Scientists say they didn’t have a proper context or verbal sentences. Instead they had calls like animals. He used to communicate or call each other through specific set of music, shrieks, cries or calls. They had separate calls for expressing joy , sorrow or giving signals for any danger lurking nearby.

Man started using different materials for building his home- like straw, wood, mud, bamboo and wood. With the advent of fire and wood man made another discovery that changed the pace of time. He discovered metals. He discovered ores from which metals can be formed. The very first metal to be discovered was copper.

Man can now store food. Before he used to store milk in earthen pots or skins of animals hence the food got easily wasted. But with copper utensils now he can store food easily for days. Food production became super functional. Man started producing food more than he needed. This gave him the idea of trade. He traded his grains for cattle or new weapons and utensils.

Such is the journey of man. This by and by gave rise to huge and renowned civilizations which shaped our future-like the Mayans, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Indus valley and many more. What we are now is because of them

“ For men may come, and men may go, but I go on forever ” -the river

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Top Trending Essays in March 2021

- Essay on Pollution

- Essay on my School

- Summer Season

- My favourite teacher

- World heritage day quotes

- my family speech

- importance of trees essay

- autobiography of a pen

- honesty is the best policy essay

- essay on building a great india

- my favourite book essay

- essay on caa

- my favourite player

- autobiography of a river

- farewell speech for class 10 by class 9

- essay my favourite teacher 200 words

- internet influence on kids essay

- my favourite cartoon character

Brilliantly

Content & links.

Verified by Sur.ly

Essay for Students

- Essay for Class 1 to 5 Students

Scholarships for Students

- Class 1 Students Scholarship

- Class 2 Students Scholarship

- Class 3 Students Scholarship

- Class 4 Students Scholarship

- Class 5 students Scholarship

- Class 6 Students Scholarship

- Class 7 students Scholarship

- Class 8 Students Scholarship

- Class 9 Students Scholarship

- Class 10 Students Scholarship

- Class 11 Students Scholarship

- Class 12 Students Scholarship

STAY CONNECTED

- About Study Today

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Scholarships

- Apj Abdul Kalam Scholarship

- Ashirwad Scholarship

- Bihar Scholarship

- Canara Bank Scholarship

- Colgate Scholarship

- Dr Ambedkar Scholarship

- E District Scholarship

- Epass Karnataka Scholarship

- Fair And Lovely Scholarship

- Floridas John Mckay Scholarship

- Inspire Scholarship

- Jio Scholarship

- Karnataka Minority Scholarship

- Lic Scholarship

- Maulana Azad Scholarship

- Medhavi Scholarship

- Minority Scholarship

- Moma Scholarship

- Mp Scholarship

- Muslim Minority Scholarship

- Nsp Scholarship

- Oasis Scholarship

- Obc Scholarship

- Odisha Scholarship

- Pfms Scholarship

- Post Matric Scholarship

- Pre Matric Scholarship

- Prerana Scholarship

- Prime Minister Scholarship

- Rajasthan Scholarship

- Santoor Scholarship

- Sitaram Jindal Scholarship

- Ssp Scholarship

- Swami Vivekananda Scholarship

- Ts Epass Scholarship

- Up Scholarship

- Vidhyasaarathi Scholarship

- Wbmdfc Scholarship

- West Bengal Minority Scholarship

- Click Here Now!!

Mobile Number

Have you Burn Crackers this Diwali ? Yes No

- Fundamentals NEW

- Biographies

- Compare Countries

- World Atlas

human origins

Introduction.

Modern humans evolved in stages from a series of ancestors, including several earlier forms of humans. The bodies of these ancestors changed over time. In general, their brains became larger. The jaws and teeth became smaller. Human ancestors also began walking upright on two feet and using tools. As they did, the shape of their legs, feet, hands, and other body parts changed.

Apes and Humans

Humans did not evolve from apes . Instead, modern humans and apes both developed from the same apelike ancestor. The ancestors of humans became separate from the ancestors of apes between about 8 million and 5 million years ago. After that each group developed on its own.

Modern humans and apes are still closely related. In fact, most scientists consider humans and great apes—chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans—to belong to the same scientific family. But there are many important differences between humans and apes. For this reason scientists have divided the family into smaller groups. Orangutans belong to a group called Ponginae. Gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos belong to a group called the Gorillini tribe. Humans belong to the Hominini tribe. The term hominin refers to humans and all their ancestors from the time they began developing separately from those of apes.

Today only one species, or type, of hominin exists—modern humans. In the past, two or more species of hominin often lived at the same time. Scientists do not always agree about which species are the direct ancestors of other species. But all hominins are closely related.

Australopithecines

Some of the earliest hominins are known as australopithecines. There were several different species of this group. Fossils show that they lived in Africa from roughly 4 million to 2.5 million years ago. One of the most famous such fossils is “Lucy”—a partial skeleton found in Ethiopia. These bones are about 3 million years old.

The australopithecines had some apelike features. For instance, their brains were much smaller than modern human brains. They could also climb trees easily. But, like humans, they walked on two feet. Scientists know this from studying leg, knee, foot, and pelvis fossils. In addition, they found a set of footprints preserved in the ground in Tanzania.

Early forms of humans first existed more than 2 million years ago. All species of humans belong to a scientific group within the hominin tribe called Homo. The scientific names of all human species begin with the word Homo , which means “man.” These early humans had larger brains and mostly smaller teeth and jaws than the australopithecines. Their behavior was probably also more like that of modern humans. For instance, an early human species called Homo habilis used stone tools to butcher animals. Later human species included Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis . Scientists believe that these humans used fire to cook food.

The humans called Neanderthals were alive for part of the same time as modern humans. The Neanderthals died out about 28,000 years ago. They were closely related to modern humans. But most scientists think that these humans were not the direct ancestors of modern humans.

It’s here: the NEW Britannica Kids website!

We’ve been busy, working hard to bring you new features and an updated design. We hope you and your family enjoy the NEW Britannica Kids. Take a minute to check out all the enhancements!

- The same safe and trusted content for explorers of all ages.

- Accessible across all of today's devices: phones, tablets, and desktops.

- Improved homework resources designed to support a variety of curriculum subjects and standards.

- A new, third level of content, designed specially to meet the advanced needs of the sophisticated scholar.

- And so much more!

Want to see it in action?

Start a free trial

To share with more than one person, separate addresses with a comma

Choose a language from the menu above to view a computer-translated version of this page. Please note: Text within images is not translated, some features may not work properly after translation, and the translation may not accurately convey the intended meaning. Britannica does not review the converted text.

After translating an article, all tools except font up/font down will be disabled. To re-enable the tools or to convert back to English, click "view original" on the Google Translate toolbar.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Did Humans Evolve?

By: Becky Little

Updated: October 4, 2023 | Original: March 5, 2020

The first humans emerged in Africa around two million years ago, long before the modern humans known as Homo sapiens appeared on the same continent.

There’s a lot anthropologists still don’t know about how different groups of humans interacted and mated with each other over this long stretch of prehistory. Thanks to new archaeological and genealogical research, they’re starting to fill in some of the blanks.

The First Humans

First things first: A “human” is anyone who belongs to the genus Homo (Latin for “man”). Scientists still don’t know exactly when or how the first humans evolved, but they’ve identified a few of the oldest ones.

One of the earliest known humans is Homo habilis , or “handy man,” who lived about 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago in Eastern and Southern Africa. Others include Homo rudolfensis , who lived in Eastern Africa about 1.9 million to 1.8 million years ago (its name comes from its discovery in East Rudolph, Kenya); and Homo erectus , the “upright man” who ranged from Southern Africa all the way to modern-day China and Indonesia from about 1.89 million to 110,000 years ago.

In addition to these early humans, researchers have found evidence of an unknown “superarchaic” group that separated from other humans in Africa around two million years ago. These superarchaic humans mated with the ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans , according to a paper published in Science Advances in February 2020. This marks the earliest known instance of human groups mating with each other—something we know happened a lot more later on.

Early Humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans Mixed It Up

After the superarchaic humans came the archaic ones: Neanderthals, Denisovans and other human groups that no longer exist.

Archaeologists have known about Neanderthals, or Homo neanderthalensis , since the 19th century, but only discovered Denisovans in 2008 (the group is so new it doesn’t have a scientific name yet). Since then, researchers have discovered Neanderthals and Denisovans not only mated with each other, they also mated with modern humans.

“When the Max Plank Institute [for Evolutionary Anthropology] began getting nuclear DNA sequenced data from Neanderthals, then it became very clear very quickly that modern humans carried some Neanderthal DNA ,” says Alan R. Rogers , a professor of anthropology and biology at the University of Utah and lead author of the Science Advances paper. “That was a real turning point… It became widely accepted very quickly after that.”

As a more recently-discovered group, we have far less information on Denisovans than Neanderthals. But archaeologists have found evidence that they lived and mated with Neanderthals in Siberia for around 100,000 years. The most direct evidence of this is the recent discovery of a 13-year-old girl who lived in a cave about 90,000 years ago. DNA analysis revealed that her mother was a Neanderthal and her father was a Denisovan.

Human Evolution Was Messy

Scientists are still figuring out when all this inter-group mating took place. Modern humans may have mated with Neanderthals after migrating out of Africa and into Europe and Asia around 70,000 years ago. Apparently, this was no one-night stand — research suggests there were multiple encounters between Neanderthals and modern humans.

Less is known about the Denisovans and their movements, but research suggests modern humans mated with them in Asia and Australia between 50,000 and 15,000 years ago.

Until recently, some researchers assumed people of African descent didn’t have Neanderthal ancestry because their predecessors didn’t leave Africa to meet the Neanderthals in Europe and Asia. But in January 2020, a paper in Cell upended that narrative by reporting that modern populations across Africa also carry a significant amount of Neanderthal DNA. Researchers suggest this could be the result of modern humans migrating back into Africa over the past 20,000 years after mating with Neanderthals in Europe and Asia.

Given these types of discoveries, it may be better to think about human evolution as a “braided stream,” rather than a “classical tree of evolution,” says Andrew C. Sorensen , a postdoctoral researcher in archaeology at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Although the majority of modern humans’ DNA still comes from a group that developed in Africa (Neanderthal and Deniosovan DNA accounts for only a small percentage of our genes), new discoveries about inter-group mating have complicated our view of human evolution.

“It seems like the more DNA evidence that we get—every question that gets answered, five more pop up,” he says. “So it’s a bit of an evolutionary wack-a-mole.”

Early Human Ancestors Shared Skills

Human groups that encountered each other probably swapped more than just genes, too. Neanderthals living in modern-day France roughly 50,000 years ago knew how to start a fire , according to a 2018 Nature paper on which Sorensen was the lead author. Fire-starting is a key skill that different human groups could have passed along to each other—possibly even one that Neanderthals taught to some modern humans.

“These early human groups, they really got around,” Sorensen says. “These people just move around so much that it’s very difficult to tease out these relationships.”

HISTORY Vault: Mankind The Story of All of Us

A look at how the human race has survived throughout the ages.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Support Our Work

The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

Human evolution evidence.

Evidence of Evolution

Scientists have discovered a wealth of evidence concerning human evolution, and this evidence comes in many forms. Thousands of human fossils enable researchers and students to study the changes that occurred in brain and body size, locomotion, diet, and other aspects regarding the way of life of early human species over the past 6 million years. Millions of stone tools, figurines and paintings, footprints, and other traces of human behavior in the prehistoric record tell about where and how early humans lived and when certain technological innovations were invented. Study of human genetics show how closely related we are to other primates – in fact, how connected we are with all other organisms – and can indicate the prehistoric migrations of our species, Homo sapiens , all over the world. Advances in the dating of fossils and artifacts help determine the age of those remains, which contributes to the big picture of when different milestones in becoming human evolved.

Exciting scientific discoveries continually add to the broader and deeper public knowledge of human evolution. Find out about the latest evidence in our What’s Hot in Human Origins section.

Explore the evidence of early human behavior—from ancient footprints to stone tools and the earliest symbols and art – along with similarities and differences in the behavior of other primate species.

Human Fossils

From skeletons to teeth, early human fossils have been found of more than 6,000 individuals. Look into our digital 3-D collection and learn about fossil human species.

3D Collection

Explore our 3D collection of fossils, artifacts, primates, and other animals.

Our genes offer evidence of how closely we are related to one another – and of our species’ connection with all other organisms.

As plants and animals die, their remains are sometimes preserved in Earth’s rock record as fossils.

Human Evolution Interactive Timeline

Explore the evidence for human evolution in this interactive timeline - climate change, species, and milestones in becoming human.

Zoom in using the magnifier on the bottom for a closer look! This interactive is no longer in FLASH , it may take a moment to load.

- Human Family Tree

The human family tree shows the various species that constitute the human evolutionary family.

Snapshots in Time

In these video interactives, put together clues and explore discoveries the prehistoric sites of Swartkrans, South Africa, Olorgesailie, Kenya, and Shanidar Cave, Iraq.

- Climate Effects on Human Evolution

- Survival of the Adaptable

- Human Evolution Timeline Interactive

- 2011 Olorgesailie Dispatches

- 2004 Olorgesailie Dispatches

- 1999 Olorgesailie Dispatches

- Olorgesailie Drilling Project

- Kanam, Kenya

- Kanjera, Kenya

- Ol Pejeta, Kenya

- Olorgesailie, Kenya

- Evolution of Human Innovation

- Adventures in the Rift Valley: Interactive

- 'Hobbits' on Flores, Indonesia

- Earliest Humans in China

- Bose, China

- Anthropocene: The Age of Humans

- Fossil Forensics: Interactive

- What's Hot in Human Origins?

- Instructions

- Carnivore Dentition

- Ungulate Dentition

- Primate Behavior

- Footprints from Koobi Fora, Kenya

- Laetoli Footprint Trails

- Footprints from Engare Sero, Tanzania

- Hammerstone from Majuangou, China

- Handaxe and Tektites from Bose, China

- Handaxe from Europe

- Handaxe from India

- Oldowan Tools from Lokalalei, Kenya

- Olduvai Chopper

- Stone Tools from Majuangou, China

- Middle Stone Age Tools

- Burin from Laugerie Haute & Basse, Dordogne, France

- La Madeleine, Dordogne, France

- Butchered Animal Bones from Gona, Ethiopia