ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The philippine teachers concerns on educational reform using concern based adoption model.

- Department of Education, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, South Korea

This study aims to identify the Philippines teachers’ concerns in K–12 implementation. The Concerns Based Adoption Model was applied to determine the level of concerns, and the Stages of Concern Questionnaire has been administered to 400 teachers. Findings indicate that consequence and collaboration was the teachers’ current concern (impact stage). Furthermore, experience and education factors showed the biggest significance affecting their collaboration among teachers. These current concerns match the existing problems of Philippine education: poor PISA results and lack of resources. This research urges the Philippine government to promote professional development activities that encourage teamwork and collaboration among teachers.

1 Introduction

The approval of the Republic Act 10,533 (Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 or K–12 law) reformed the entire education system of the Philippines including curriculum, teacher training, and offered programs ( Tamar and Atinc, 2017 ). Schools are expected to be the training ground for students to prepare them for the real world. As the curriculum is used as the blueprint on what students should learn, the teaching force plays the biggest role in delivering this essential information to the students ( Redondo, Jr. and Bueno, 2019 ). With the new program implementation in the Philippines, teachers’ response to this new policy should also be taken into consideration. As stated by Fritz (2001, as cited in Tuytensa and Devosab, 2009 ), teachers are susceptible to different outlooks to policy change hence it is essential to understand how teachers view the policy and it’s characteristics.

Educators and policymakers are responsive in implementing change and policies to suit the following needs of the students, teachers, and the educational environment. Educational developments and modifications in education require proactive participation and response from the teachers. Therefore, the teacher’s preparedness and self-regulation are essential for them to deliver proper instruction and exert their influence in the classroom ( Bray-Clark and Bates, 2003 ). To study these educational innovations and arising concerns surrounding them, the Concerns Based Adoption Model (CBAM) became one of the most effective frameworks and an “empirically grounded model” for implementation analysis ( Anderson, 1997 ). CBAM was conceptualized by Gene Hall and defines, describes, and predicts the possible levels of teacher concerns and behaviors during implementation ( Hall et al., 1979 ; Hall and Hord, 1987 ; Hall and Hord, 2001 ). The CBAM model can be utilized in various ways by using the tools for measuring the process of implementation like curriculum developments, school programs, etc. Significantly in the field of education, CBAM can aid in the field of education through the following reasons: (1) evaluate the effects of reform programs or initiatives for educators and recognize the dynamic structure of the educational organization which involves the interplay within various key players; (2) contains a “conceptual framework for change” that thoroughly recommends an effective change implementation and understand the individuals involved in the change process through the three dimensions of CBAM; and (3) study the individuals’ feelings, perceptions, behavior, and professional development ( Saunders, 2012 , pp. 187–188). The CBAM model consists of three dimensions: seven Stages of Concerns (SOC), eight Levels of Use (LoU), and innovation configurations. For this research, the focus will be on the seven SOC which consists of the Unconcerned/Awareness, Informational, Personal, Management, Consequence, Collaboration, and Refocusing stages ( George et al., 2013 ).

Considering the impact and importance of teachers in any educational implementation, it is important to investigate the basis of teachers’ concerns regarding the adoption process. Hence, the present study examines the concerns Filipino teachers have in response to new situations or demands emerging from the adoption of the K–12 educational system. The teacher’s ability to face different challenges and self-regulation is essential for them to deliver proper instruction and exert their effects in the classroom ( Bray-Clark and Bates, 2003 ). For this research, the following questions will be explored: (1) Among the seven stages on the CBAM, what is the current concerns level of the teachers regarding the new K–12 implementation and the difference across teachers’ experience and involvement with the innovation? and (2) What are the factors affecting the current level of concern on the K–12 implementation? Due to the nature of the new educational reform, recent research is directed more on the new system and its implementation process. Hence, there is currently a gap in the literature focusing on the teacher’s development and sentiments towards the reform. As Department of Education Secretary Leonor Briones highlighted their intention to thoroughly review the K–12 educational program ( Montemayor, 2018 ), it is integral to assess the teacher’s level of preparedness by learning their personal insights on their own standing in the educational reform. This research will aid in understanding the current impact of the education reform on the teachers and students, and what should be the main points and focus on improvement.

1.1 Theoretical Background: Educational Reform and Teachers’ Concerns

1.1.1 k–12 educational reform in the philippines.

The Republic Act of 10,533 or Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 (K–12) is one of the biggest reforms the Philippines has experienced after more than 50 years of having a 10-years educational system. The most significant contribution brought by this reform is the additional 2 years of Senior High School (SHS) which makes the new system befitting to international standards ( Oxford Business Group, 2021 ). Moreover, all technical and vocational courses are also offered to prepare students to join the workforce ( Barlongo, 2015 ). The adoption and implementation process of the K–12 system has been a well-discussed matter before its execution. In the Transitions to K–12 Education Systems: Experiences from Five Case Countries publication prepared by the Asian Development Bank, they enumerated eight factors that influenced the reform in the Philippines: large size, secondary lags, low cycle completion, inequality, academic test performance, teacher development, public-private partnership, and education spending recovering ( Sarvi et al., 2015 ). Hence, in 2010, the administration prioritized educational reform, and meticulously planned for the enactment of the Republic Act of 10,533 or the Enhanced Basic Education Act (CHED, n, d). This educational reform is set not just to simply meet the global standards but to also assure that the next generation of graduates would be at par and on a level with the rest of the world.

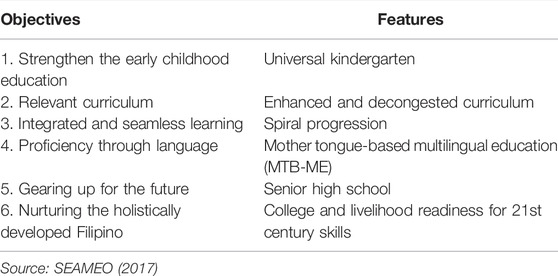

The Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization or SEAMEO (2017) stated that K–12 holds a set of objectives: aligning the system with the international standard, refining the youth’s educational experience, and boosting the country’s competitiveness. Table 1 shows the specific objectives and corresponding features of the K–12 education system:

TABLE 1 . Programs based on K–12 objectives.

The implementation of this program started in the year 2011 and the first batch of Senior High School students graduated by 2018. Figure 1 shows the yearly plan of the government and their targeted years for the new batch undergoing the K–12 system. Based on the plan, the universal Kindergarten started in 2011, while the Grade 7 and the new Grade 1 curriculum were implemented by the following year. In 2016, the first Senior High School program began and hence the first batch of Senior High School students graduated in the year 2018.

FIGURE 1 . Interaction effect between involvement in innovation and teaching experience.

The Basic Education is now compulsory for all and is structured based on the following: Kindergarten or Early Childhood Education, 6 years of Elementary or Primary Education (Grade 1–6), 4 years of Secondary/Junior High School (Grade 7–10), and 2 years of Senior High School (Grade 11–12). After graduating from high school, students can opt to attend a Technical Vocational Education and Training Program (TVET) and/or Higher Education. Students can start Kindergarten from the age of 5 and are expected to enter their last year of Senior High School by the age of 17 ( Sarvi et al., 2015 ).

1.1.2 Teachers’ Concerns on the K–12 Implementation

According to Vilches (2017) , teachers’ impact and performance are considered a huge influence on the success and failure of educational reforms; hence, implementing reforms and programs should be done alongside teachers. The sudden implementation of the K–12 in the Philippines left teachers in confusion with their roles in the new educational system, specifically the development of their roles throughout the process, the appropriateness of the new curriculum and the real classroom situation, and the difference in the internal communication of different education stakeholders. A study conducted by Braza and Supapo (2014) about the problems of the Mathematics curriculum under the K–12 education system showed that there are three main problems in the implementation: administrative, teacher-related, and student-related. The teachers were discovered to struggle in delivering the content of class materials and possess poor teaching strategies/skills. Due to the lack of professional development opportunities, teachers were unprepared to teach the content based on the assigned schedule and have a more diversified teaching methodology. Moreover, the absence of proper support and materials led to lesser time for teachers to efficiently instruct the content. Dizon et al. (2019) further supported this claim stating that there is a lack of preparation for teaching development. It is necessary that teachers themselves must be well-equipped with proper teaching strategies that maximize teacher-student participation.

Outside the four walls of the classroom, various concerned groups in the Philippines like Alliance of Concerned Teachers Partylist Representatives Antonio Tinio and France Castro strongly expressed that the Philippines was not yet ready for the full implementation of the K–12 system. They expressed that there is a “persisting shortages in school and classrooms, particularly senior high school; lack of textbook, learning facilities, and other needs of students.” Teachers were also left to shoulder the expenses on their own ( Tibay, 2018 ). The ACT noted that the Department of Education is already late in reviewing the implementation process; nonetheless, they are hoping that both the DepEd and Congress will have an “honest-to-goodness review” of the first run of the implementation to show the lapses and points of improvements the government can manage for the education sector ( Juntereal, 2019 ).

2 Concerns-Based Adoption Model

Hall and Hord, Hord et al., Loucks-Horsley and Stiegelbauer (as cited in in Khoboli and O’toole, 2012 , p. 140) explained that CBAM “focuses on how people, such as teachers, parents, students and policy makers, respond to change.” Moreover, it also shows the emotional and psychological processes individuals go through once they are confronted and/or adopt an innovation ( Hall, 1975 ). Under this model, there are 5 assumptions about the innovation in classroom and instruction: (1) change is a process, not an event; (2) change is executed by individuals; (3) change is an intimate personal experience; (4) change contains progressive growth in feelings and skills; (5) change can be enabled by interventions directed toward the individuals, innovations, and contexts involved ( Anderson, 1997 ).

The CBAM was inspired by the works of Frances Fuller as she theorized the “concerns theory for teacher education.” In one of her papers about Concerns of Teachers: A Developmental Conceptualization, she notes that there must be a close observation between knowing what teachers need and what is available to them. Her research contains two studies and groups of student teachers that were surveyed through a counseling method. The first study results showed that student teachers were first concerned with their “self” on how they can meet the supervisor’s expectations, deal with school authority, and perform class maintenance. This concern gradually shifted to their “students’” performance in class and effective learning. The second study showed a similar response with the first on how the student teachers’ concern shifted from “self” to “students.” In this study, the student teachers’ responses were divided into three categories: (1) Where do I stand? How adequate am I? How do others think I’m doing? [self] (2) Problem behavior of pupils. Class control. Why do they do that? [student management] (3) Are pupils learning? How does what I do affect their gain? [student concerns]. Results showed that there is a correlation in the student teachers’ concern between [1] and [2] while there is a difference between [1] and [3] and [2] and [3], which shows that there is a distinction between the flow of teachers’ concern from self to students ( Fuller, 1969 , pp. 211–214). Fuller’s work shows a developmental sequence of teachers’ concerns from themselves to student management to impact on students—the self, task, and impact concerns. Self-concerns refer to the personal dilemmas of the teacher in his/her ability to perform well; task concerns refer to the responsibilities and duties teachers need to keep in mind in managing the classroom; and lastly, impact concerns refer to the evaluation and worries of teachers in the possible effect of their teaching and management to the students ( Christou et al., 2004 ). Research works from the University of Texas conducted studies concerning the adoption of teachers and professors on certain implementation. They saw similar results with the one Fuller had before and hypothesized that there are certain categories of concerns and logical progression in the development of concerns. This led the researchers to identify the three dimensions of CBAM: seven Stages of Concerns (SOC), and eight Levels of Use (LoU), and innovation configurations ( Hall, 1975 ). Hall and Hord (2001) explained that the Stages of Concern which utilizes the Stages of Concern (SoC) questionnaire is the most important data gathering tool in the model ( George et al., 2013 ).

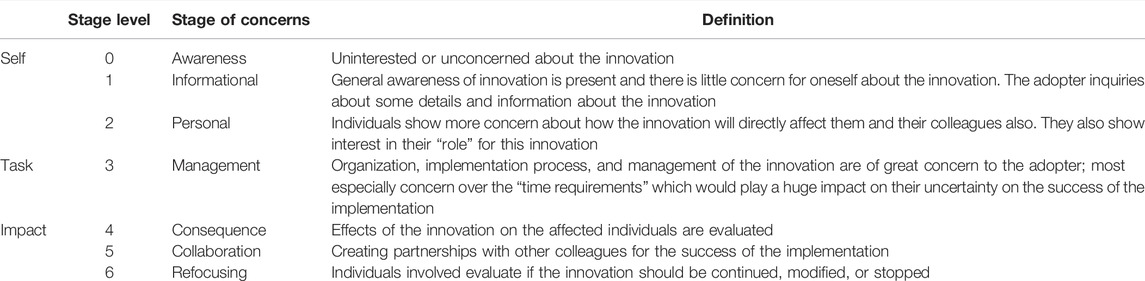

2.1 Stages of Concern

The Stages of Concern identify the individual’s worries or feelings about innovation. It is called stages because of the step-by-step development evolution of the concerns as they shift from one to another. These stages are used to determine in which part of the process the individual’s feelings are heightened. It consists of seven stages which were classified into three categories centering on Fuller’s developmental sequence of concerns: self, task, and impact ( Hall, 1975 ). Table 2 features the seven stages, their corresponding developmental sequence, and their definition.

TABLE 2 . CBAM stages of concerns.

2.2 CBAM Application

Christou et al.’s (2004) research investigated the reform in the Mathematics curriculum in Cyprus’ elementary schools. To efficiently instruct Mathematics, some developments were focused on changing the curriculum content and resource materials. Teachers were expected to assist the students to discover things by themselves rather than spoon-feeding them. Based on their research findings of curricular change, they believe that teachers are the key to the effective implementation by understanding how they handle the process. However, there seems to be a conflict between the teaching methods of teachers and reforms in the Math curriculum which led to a huge concern and frustration among teachers. Because of this, the researchers wanted to identify the concerns teachers have in the new curricula and Mathematics textbooks in Cyprus. They wanted to look at the “degree to which Cypriot teachers had accepted and followed it in the classroom.” Also, they wanted to see if there is any difference between the teacher’s experience in the education field and their involvement with the implementation. The participants consist of 155 male and 500 female teachers coming from 100 elementary schools in Cyprus. The researchers utilized their own adapted version of the Stages of Concern Questionnaire which includes 36 items and can be answered based on a 9-item Likert scale—ranging from Strongly Disagree [1] to Strongly Disagree [9]. Since the questionnaire was modified, factor analysis was done to check the validity of the questionnaire. Answering the two main research questions, the first result of the study showed that the informational and personal stages have the highest mean showing that teachers were acquainted with the objectives and philosophy of the Mathematics book. Meanwhile, the management stages (task) garnered a low mean value expressing those teachers were more concerned about their ability to deliver the objectives of the material. The fewer focus teachers had in their “self” phase showed that they are less concerned with starting the implementing the Mathematics curriculum since they had experiences with the implementation of other innovations before. Moreover, it was hypothesized that the more teachers overcome the task stage, the higher chances they will have little concerns over the impact phase of the development of concerns. The second result showed that teachers with more experience scored higher in the personal and informational stages than the beginning teachers. Highly experienced teachers, even in the absence of full information on the implementation, have more confidence in dealing with innovation. Beginning teachers showed more concern in collaborating with other colleagues and work than the consequence of the implementation on their students ( Christou et al., 2004 ).

In the case of Jordanian universities, CBAM was used to evaluate the E-learning system and check the “current stage of concern” of the faculty members in 12 Jordanian universities. A total of 400 faculty members received the questionnaire, and 138 faculty members finished the questionnaire. The responses were analyzed through the SPSS program. Results showed that teachers’ highest level of concern was on the informational stage which had 83%, which was followed by the management stage with 73%. These results showed that teachers are curious about using the E-learning system and the requirements needed to fulfill this system. The lowest group percentages are from Awareness (54%), Refocusing (55%), Collaboration (56%), and Consequence (59%). Based on Fuller’s developmental sequence of concerns, the lowest percentages are under the impact level, which means that teachers need more training on the use of the e-learning system to push their focus from personal concerns to the impact of the system on their students and on others ( Matar, 2015 ).

3 Methodology

This study follows cross-sectional research which aims to identify the current stage Philippine teachers are in regarding the K–12 educational implementation. The participants were chosen via random sampling and were asked to answer an online survey. The survey was distributed with the permission of the respective department of education branches and the researchers contacted the head or principals of different schools for assistance. The number of responses collected consists of 400 participants from different elementary and secondary private and public schools in the Philippines.

3.1 Data Analysis

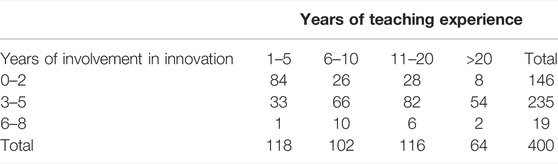

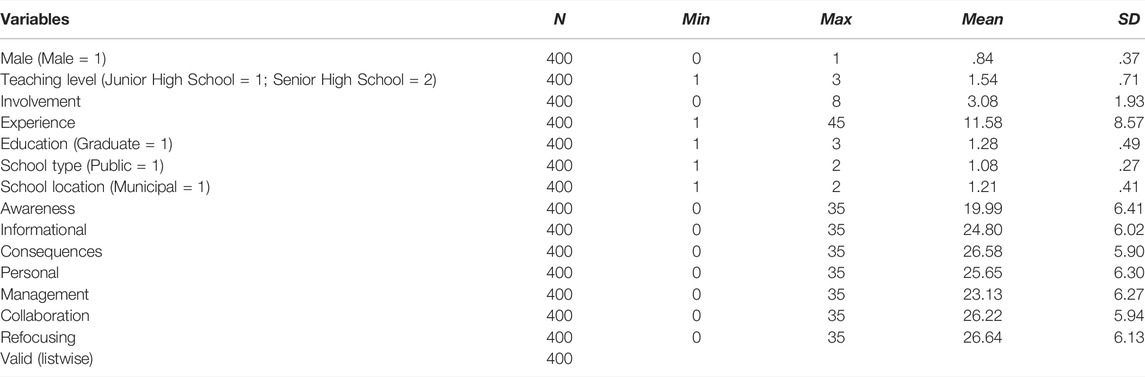

For the 1st question, the independent variables of the study were the teachers’ total teaching experience and the years of their involvement in the implementation of the new educational system in the Philippines, and the dependent variables are the seven stages of concerns. Based on the study, four groups of teachers were dispersed across the whole range of teaching experience, and three groups covered the years of involvement with the innovation. Table 3 presents the numbers of teachers in each group. To answer research question 1, the mean and standard deviation will be computed to check the relationship between the levels and teachers’ experience and involvement with the innovation. The second question seeks to determine the factors affecting the teachers’ current stage of concern. To compute this, the regression analysis was done. Gender, Education level, School Type, School Location, Mountain area, and Teaching Level were chosen as predictors to determine the personal profiles and working (school) environment of the teachers. Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the following variables and predictors mentioned above.

TABLE 3 . Teachers involvement by years of teaching experience and years of involvement in the innovation.

TABLE 4 . Descriptive statistics for the Philippine teachers.

3.2 Instrumentation: Concern Scales

The Stages of Concern Questionnaire (SoCQ) was adopted as the data gathering tool for this research. Before the 35-item questionnaire was finalized, a 195-item instrument was analyzed using the item-scale score correlation and content analysis to avoid redundancy of the items which led researchers to decrease the items to 35 with 5 items per scale. This 35-item questionnaire was conducted in various research settings such as a cross-sectional and longitudinal study to a number of educational innovations. Conclusive evidence shows that SoCQ was able to accurately measure the Stages of Concerns, and at the same time shows reliability and validity ( Hall et al., 1979 ).

For this study, the SoCQ includes a set of scales to prepare a numerical representation of the level and possible causes of concerns toward the Philippines’ educational innovation. Specific words such as “10-years education system” were added to fit the context of the Philippines’ educational system innovation. The adopted SoCQ included a total of 37 items: 35 items for the statements/items where participants are asked to choose on a 0–7 Likert Scale: 0 = Irrelevant, 1 = Not True of Me Now, 2 = Not True of Me Now, 3 = Somewhat True of Me Now, 4 = Somewhat True of Me Now, 5 = Somewhat True of Me Now, 6 = Very True of Me Now, and 7 = Very True of Me Now. The remaining 2 items inquire about the year of involvement in the innovation and their training in preparation for the innovation. As per the SoCQ manual, the order of the items was kept in their exact order to avoid risks of reliability and validity.

Before analysing the variance and regression of the data, a reliability analysis was carried out on the CBAM scale comprising 7 items. Cronbach’s alpha showed the questionnaire to reach acceptable reliability, α = 0.90. The Cronbach alphas for all stages were high except for the Awareness stage which got α = 0.66. Nonetheless, the values of the alphas show that the instrument has acceptable reliabilities for the study. The alphas for each stage are as follows: (Informational α = 0.91, Personal α = 0.90, Management α = 0.85, Consequences α = 0.85, Collaboration α = 0.85, and Refocusing α = 0.88).

4.1 Research Question 1: Teachers’ Current Stage of Concern Across Experience and Involvement

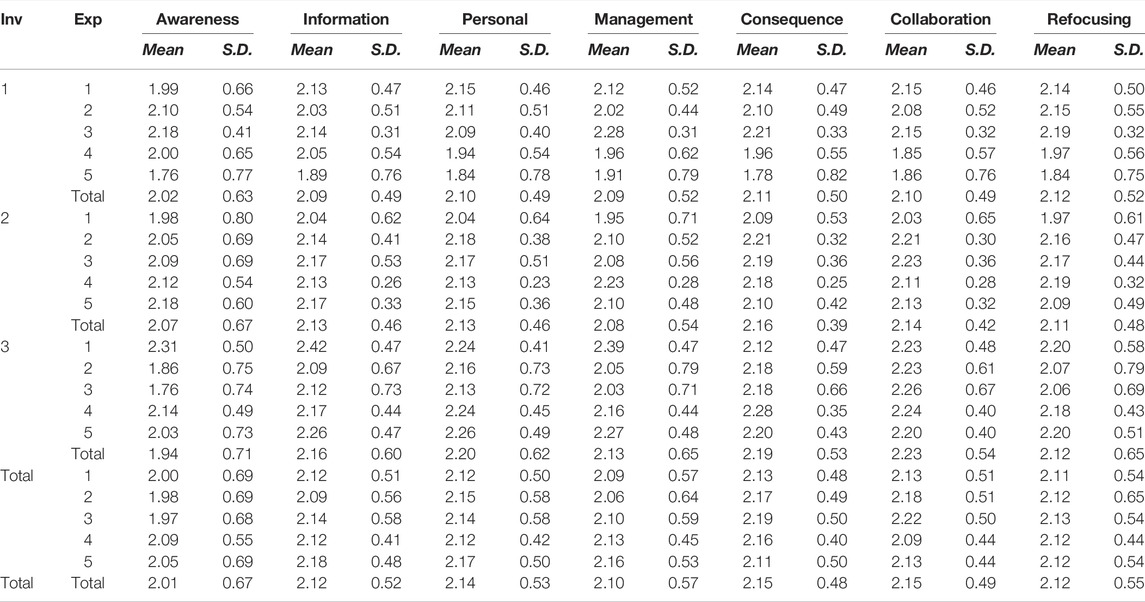

Table 5 shows the mean and standard deviation responses in relation to the teacher’s experience and involvement in the innovation. Analyzing the table, the low mean value of Awareness (x̄ = 2.00) shows that teachers were all well-informed about the innovation given that frequent discussions and concerns have been raised by education-related organizations and even some private and public sectors. Moreover, because they were already involved with this innovation for a sufficient period, their awareness stage is on a low level.

TABLE 5 . Means of SoC by teachers’ experience and by teachers’ years of involvement in the innovation.

The next stage, Task stage (Management, x̄ = 2.1) has a lower mean compared to the Self Stage: Awareness (x̄ = 2.00), Information (x̄ = 2.12), and Personal (x̄ = 2.14). However, it has a relatively low mean average compared to that of the impact stage (Consequence, x̄ = 2.15; Collaboration, x̄ = 2.15; Refocusing, x̄ = 2.12). This means that teachers were now focusing on how to achieve their class objectives, assessing the students’ performance, and achieving the end goal of the innovation. Thus, it can be hypothesized that as the teachers under the new K–12 education became used to the new implementation, their concerns are more on finding ways for students to adapt to the new educational program.

The highest means can be seen on the Consequence (x̄ = 2.15) and Collaboration stages (x̄ = 2.15), indicating that the teachers are now more concerned about the effects of the implementation on their students and their colleagues’ activity. Under the consequence stage, teachers are more focused on the impact and relevance of the innovation to the students, educational outcomes, and changes needed for better student outcomes ( George et al., 2013 ). Anderson (1997) further explained this stage where teachers will also try to modify the innovation or their application to see better effects. The Collaboration stage, on the other hand, also shows the teachers’ willingness to work with others for the utilization and improvement of the implementation. As seen in the table, both the Consequence and Collaboration stages fall under the category of Impact which shows that teachers are now on the stage of worrying whether the implementation has a positive impact on their students’ lives.

4.2 Research Question 2: Factors Affecting the Current Level of Concern

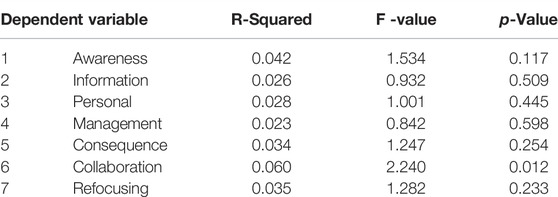

To identify which factors of the CBAM were strongly related to each stage, we conducted a regression analysis using the CBAM stages as the dependent variables. The CBAM stages are divided into seven and Gender, Education level, School Type, School Location, Mountain area, and Teaching Level were used as predictors. We also calculated the interaction effect between Involvement with Innovation and Teaching Experience. Before checking which factors of the CBAM were strongly related to each stage, the coefficients were checked to see which stage gives the best level of significance and can be analyzed for this question.

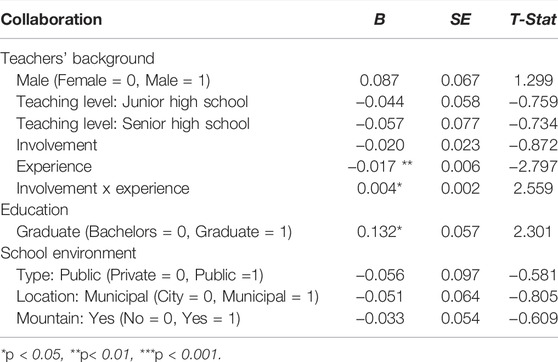

As presented in Table 6 , Collaboration ( p = 0.012) showed the strongest significance among the seven. Based on their r-squared, the collaboration ( R 2 = 0.060) stage showed the highest significance among the seven. Table 7 illustrates the regression analysis with the chosen predictors for this study. The low R 2 value for this study can be attributed to the hard differentiation of human behavior towards the change process ( Frost, 2021 ). Achen (1977, as cited in Figueiredo Filho et al., 2011 ) also noted that the small R 2 value is not a sign of a weak relationship among variables. The variance interpreted from the R 2 can depend on the variation of the variables included in the study. Interpreting the significance of this study can also be seen from both the statistical and practical significance. Statistical significance focuses on the p -value (null hypothesis) while, on the other hand, practical significance observes the effect size and usefulness of the results based on the field of study. In short, a study that may not be statistically significant can still be practically important. One example is the area of Gene and Environmental study; the effect size of .01 can be considered as a significant effect size even if the value is small ( Lawrence, 2017 ).

TABLE 6 . Coefficients table for the CBAM stages.

TABLE 7 . Regression results with the Collaboration Stage regressed on multiple predictors.

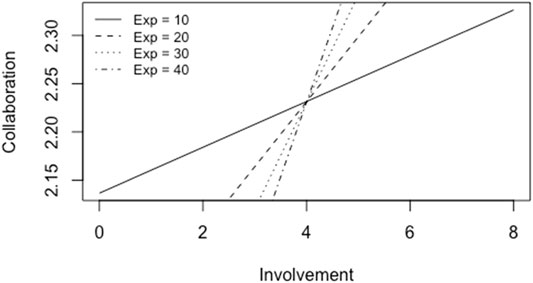

Under the Collaboration stage, the highest significant effect is shown on teachers with years of experience, followed by education and the interaction effect for involvement and experience. For the education factor, teachers with a graduate degree, either master’s or doctorate, showed a significant result showing that there is an increase in the collaboration sense for teachers who had their graduate degree. Teachers who have more teaching experience tend to seek lesser collaboration with colleagues or any individuals. However, the interaction effect between involvement with innovation and experience showed significant results. As the teacher gains more years of involvement with the innovation and teaching experience, the more they tend to be open for collaboration. The line chart below shows the relationship of involvement and collaboration, assuming that experience is at 10, 20, 30, and 40 years. It is observable that levels of collaboration tend to increase at levels of involvement, and as the levels of experience increase, there is a higher rate of increase of collaboration per year of involvement. Hence, there is a higher impact of involvement to collaboration if the teachers have more teaching experience.

5 Discussion

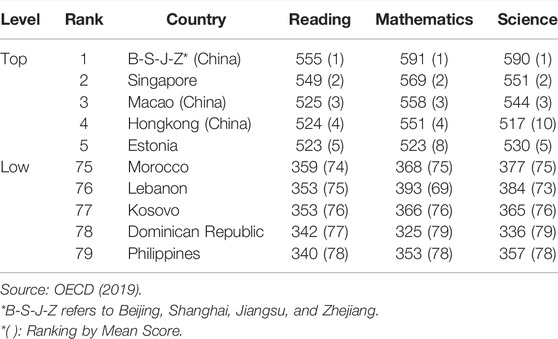

In the present study, the current level of teachers’ concern, as shown in Table 2 , shows their concern for the innovation consequences and need for collaboration. This result can be attributed to the recent result of the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). PISA is an examination given by OECD to 15-year-olds, was participated for the first time in 2018 by the Philippines to evaluate their current global standing. Unfortunately, the country performed worse among the 79 participating countries—ranking last with an average score of 340 points which is lower than the global 487 average ( Punongbayan, 2019 ). Table 8 shows the Reading, Mathematics, and Science scores of the 5 top- and low-ranking countries in the 2018 PISA.

TABLE 8 . PISA 2018 results of the 5 top and low countries.

As the students who experienced the first run of the K–12 implementation in 2018, the result above is a wake-up call for all the education stakeholders. More importantly, this is where the greatest concern of the teachers lies—on whether the current and teaching method is effective to the students. ACT France Castro specifically pointed out the “congested curriculum” as a huge contributing factor to the poor performance in the international assessment. According to him, the curriculum negatively influences the performances of the teachers and students as it jeopardizes the teaching time and the period of student learning ( Corrales, 2020 ). Moreover, this so-called “chopseuy method,” a coined teaching method where teachers try to teach a bit of each lesson, defeats the purpose of the mastery of content and teacher’s pedagogy ( Manuel, 2020 ). Unless the government decides to restructure the curriculum, students will graduate with lesser learnings and the PISA results will stay on the bottom tier. These problems raise the concerns of teachers to seek effective ways either through professional development or collaborating with their co-teachers to discover more teaching methods.

Suggesting collaboration among colleagues or any professional educator presents as a good solution to this disheartening result. Lara-Alecio et al. (2012) and Goddard et al. (2010) documented that teachers who were involved in collaborative activities had their students score higher in Science, Mathematics, and Reading assessments. Creating a positive community among the teachers where they can share ideas and teaching methods and lessen the stressors for teachers can directly impact not only the teachers’ personal needs but also support the students more on their educational journey. With all the issues surrounding the K–12 implementation, the Philippine government needs to strengthen its teaching force by providing sufficient materials and resources for teachers to utilize. Adding co-teaching programs will also be helpful to students who are lagging or needs educational attention are supported during and even after the class.

5.1 Collaborative Education for Effective Learning

Among the seven stages of concerns, collaboration showed significance for both research questions. An effective collaboration aims for not only personal development but also benefits the group which is achievable through proper cooperation with each other—a “community of learners and support” focusing on the social aspects of education ( Head, 2003 ) Previous research findings ( Lee and Smith, 1996 ; Goddard et al., 2007 ; Berry et al., 2009 ; Louis et al., 2010 ; Dumay et al., 2013 ) showed that encouraging collaboration among colleagues leads to the teacher effectiveness such as discovery effective teaching practices and better student outcomes. According to Mora-Ruano et al. (2019 ), research proved that there are benefits for teacher collaboration ( Lee and Smith, 1996 ; Louis et al., 2010 ; Dumay et al., 2013 ). Hailen (2015, as cited in Mora-Ruano et al., 2019 ) reported that Finland's 2016 curriculum reform identifies a “collaborative atmosphere” as the key to advancing the school system. Cooperating among each other in achieving the school curriculum objectives can promote teacher professional development ( Mora-Ruano et al., 2019 ). For students, collaboration benefits have improved learning and increased clarity about their intended outcomes ( Langer et al., 2003 ). Previous research ( Shachar and Shmuelevitz, 1997 ; Pounder, 1999 ; Berry et al., 2009 ; Goddard et al., 2010 ) showed that students who attended schools with high levels of teacher collaboration performed well in their school activities.

The second research question showed that teachers with higher teaching experience tend to focus less on collaborating with other teachers. Similar to other research findings ( Christou et al., 2004 ; Ronfeldt et al., 2015 ), the lesser sense of collaboration from highly experienced teachers can be attributed to their self-efficacy and background in dealing with the subtleties of classroom changes. On the other hand, the interaction effect between experience and innovation shows that as the levels of experience increase, the collaboration also increases per year of involvement. Regarding their educational background, teachers with graduate degrees showed significant results which are in contrast with previous research findings ( Puteh et al., 2011 ; Hao and Lee, 2015 ; Yea Lo, 2018 ). Other research shows that teachers have demonstrated equal concerns about the classroom system and delivering curriculum classroom content; particularly in preparing their materials and strategizing their teaching methods, teachers are distracted with their individual concerns that collaboration is not a viable option for them. In the Philippines’ case, teachers with higher education degrees than bachelors would likely engage in collaborative efforts compared to those who only have bachelors. Teachers with higher degrees are trained more on teaching pedagogy and have discovered more about the specificities of the education field. Given the lack of resources in the Philippines, these teachers are more flexible to plausible options available in their surroundings: cooperation with co-teachers.

6 Conclusion

This research was aimed to evaluate the current concerns of teachers as the first run of the K–12 implementation is done, and to see if their teaching experience and involvement with the innovation has an effect on their level concerns. Through using the CBAM questionnaire, the questions were classified into 7 stages—all can be classified into Fuller’s concerns theory for teacher education. The questions delved into topics concerning their teachers’ concerns from shifting to their decades-old 10-years system to a new K–12 system that modified not only the number of school years but also the curriculum and learning method. The data presented showed that teachers are more focused on the impact stage. Out of the three stages, consequence and collaboration showed the highest mean scores, indicating that teachers are heavily concerned about the impact of the new educational system on their students, and the ways they can do to improve their teaching methodology. We can hypothesize that Philippine teachers are now generally more concerned about two things: the influence of the innovation on their students, and professional development especially through coordination with others. Teachers are eager to know whether their students can gain sufficient knowledge from their teachings, can comprehend and learn about the things they need for school assessment and daily life, and can modify the ways of the implementation for better educational output.

The results of the study showed that educational organizations should focus more on reforming the innovation as the results and resources provided to the teachers are insufficient. Based on the issues and findings, there are three things the government should focus on now: (1) revisiting and loosening the curriculum; (2) investing in Professional Teacher Development; and (3) creating collaborative teaching programs and training. Teachers have expressed in the beginning that the proposed curriculum is hard for them to deliver, not only because of the lack of resources but also because of their insufficient skills and time. In the Philippine context, collaboration needs more work and attention as the resources and time of the teachers may be limited. Pursuing collaboration requires the cooperation of not only the teachers but also the government. Providing professional development opportunities that enable more collaborative activities among teachers is highly encouraged. If the curriculum developers can plan and create a more systematic curriculum flow, then it would help teachers to strategize their teaching methods and lesson plans. To make this more feasible, the government should invest in giving more opportunities for training and seminars. Moreover, the education department can also increase team buildings and training to open more opportunities for teachers to collaborate with each other and learn from each other’s teaching methods.

It is important to note that even if the concerning stage is in its higher stage, it does not mean that the lower-level concerns are gone. There are a lot of educational factors and individual insights that might affect and increase the concerns of some specific stages. What each education stakeholder should do is to make sure that the initial concerns—being informed of the context of the innovation, making sure that the involved individuals need and readiness are observed, and organizing and managing of innovation—are properly monitored and resolved so that teachers can focus on their roles in the classrooms. In summary, the Philippine Department of Education needs to understand that teachers, even in a different environment, are heavily concerned with the students’ welfare. Implementation efforts should focus on engaging collaboration and should also consider the availability of resources for the teachers and students. With the lack of the previous study addressing these concerns, this research hopes to contribute to the direction of the modification of the K–12 educational system.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KM conducted the data gathering and wrote the manuscript. JC edited, reviewed, and assisted in the necessary steps to proceed with the study. SL assisted in the data analysis and final review of the paper.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5C2A03093092).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anderson, S. E. (1997). Understanding Teacher Change: Revisiting the Concerns Based Adoption Model. Curriculum Inq. 27, 331–367. doi:10.1080/03626784.1997.11075495

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barlongo, C. (2015). Reforms in the Philippine Education System: The K to 12 Program. Available at: https://businessmirror.com.ph/reforms-in-the-philippine-education-system-the-k-to-12-program/ .

Google Scholar

Bray-Clark, N., and Bates, R. (2003). Self-Efficacy Beliefs and Teacher Effectiveness: Implications for Professional Development. The Prof. Educator 26, 13–22.

Braza, M. T., and Supapo, S. S. (2014). Effective Solutions in the Implementation of the K To12 Mathematics Curriculum. SAINSAB 17, 12–23.

Berry, B., Daughtrey, A., and Wieder, A. (2009). Collaboration: Closing the Effective Teaching Gap . Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED509717.pdf .(Accessed August 13, 2021).

Christou, C., Eliophotou-Menon, M., and Philippou, G. (2004). Teachers' Concerns Regarding the Adoption of a New Mathematics Curriculum: An Application of CBAM. Educ. Stud. Math. 57 (2), 157–176. doi:10.1023/b:educ.0000049271.01649 www.jstor.org/stable/4150269 (Accessed May 21, 2020)

Corrales, N. (2020). K-12 Blamed for Low Math, Science Ranks. Philippine Daily Inquirer . Retrieved June 15, 2021, from Available at: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1371337/k-12-blamed-for-low-math-science-ranks#ixzz7GqPPYcSQ .

Dizon, R. L. L., Calbi, J. S., Cuyos, J. S., and Miranda, M. (2019). Perspectives on the Implementation of the K to 12 Program in the Philippines: A Research Review. Int. J. Innovation Res. Educ. Sci. 6 (6), 757–765.

Dumay, X., Boonen, T., and Van Damme, J. (2013). Principal Leadership Long-Term Indirect Effects on Learning Growth in Mathematics. Elem. Sch. J. 114, 225–251. doi:10.1086/673198

Figueiredo Filho, D. B., Silva Júnior, J. A., and Rocha, E. C. (2011). What Is R2 All about? Leviathan (São Paulo) (3), 60. doi:10.11606/issn.2237-4485.lev.2011.132282

Frost, J. (2021). How to Interpret R-Squared in Regression Analysis. Stat. By Jim . Retrieved January 2, 2022, from Available at: https://statisticsbyjim.com/regression/interpret-r-squared-regression/ .

Fuller, F. F. (1969). Concerns of Teachers: A Developmental Conceptualization. Am. Educ. Res. J. 6 (2), 207–226. doi:10.3102/00028312006002207

George, A., Hall, G., and Stiegelbauer, S. (2013). Measuring Implementation in Schools: The Stages of Concern Questionnaire . Austin, TX: SEDL .

Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R. D., and Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation of Teacher Collaboration for School Improvement and Student Achievement in Public Elementary Schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. Rec 109, 877–896.

Goddard, Y. L., Miller, R., Larsen, R., Goddard, G., Jacob, R., Madsen, J., et al. (2010). “Connecting Principal Leadership, Teacher Collaboration, and Student Achievement,” in Paper Presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting ( Denver, CO) .

Hall, G. E., George, A. A., and Rutherford, W. L. (1979). Measuring Stages of Concern about the Innovation: A Manual for Use of the SoC Questionnaire . 2nd ed. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory .

Hall, G. E., and Hord, S. M. (1987). Change in Schools: Facilitating the Process . Albany, NY: State University of New York Press .

Hall, G. E., and Hord, S. M. (2001). Implementing Change: Patterns, Principles, and Potholes . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon .

Hall, G. (1975). “The Effects of “Change” on Teachers and Professors—Theory, Research, and Implications for Decision-Makers,” in Paper Presented at the National Invitational Conference on Research on Teacher Effects: An Examination by Policy-Makers and Researchers ( Austin, Texas .

Hao, Y., and Lee, K. S. (2015). Teachers' Concern about Integrating Web 2.0 Technologies and its Relationship with Teacher Characteristics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 48, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.028

Head, G. (2003). Effective Collaboration: Deep Collaboration as an Essential Element of the Learning Process. The J. Educ. Enquiry .

Juntereal, C. J. (2019). Public, Private Schools Call for Thorough Review of K to 12. Manila Bull. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from Available at: https://mb.com.ph/2019/10/23/public-private-schools-call-for-thorough-review-of-k-to-12/ .

Khoboli, B., and O’toole, J. M. (2012). The Concerns-Based Adoption Model: Teachers' Participation in Action Research. Syst. Pract. Action. Res 25, 137–148. doi:10.1007/s11213-011-9214-8

Langer, G., Cotton, A., and Goff, L. (2003). Collaborative Analysis of Student Work: Improving Teaching and Learning . Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development .

Lara-Alecio, R., Tong, F., Irby, B. J., Guerrero, C., Huerta, M., and Fan, Y. (2012). The Effect of an Instructional Intervention on Middle School English Learners' Science and English reading Achievement. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 49, 987–1011. doi:10.1002/tea.21031

Lawrence, E. (2017). Statistical Significance, Effect Size, and Practical Significance.

Lee, V. E., and Smith, J. B. (1996). Collective Responsibility for Learning and its Effects on Gains in Achievement for Early Secondary School Students. Am. J. Edu. 104, 103–147. doi:10.1086/444122

Manuel, P. (2020). Solon Blames K-12 Curriculum for PH's Dismal Performance in Int'l Assessments. CNN Philippines . Available at: https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2020/12/13/solon-K-12-curriculum-PH-dismal-performance-international-assessments.html (Accessed December 28, 2020).

Matar, N. (2015). Evaluating E-Learning System Use by CBAM-Stages of Concern Methodology in Jordanian Universities. World Comp. Sci. Inf. Tech. J. 5 (5), 75–81.

Montemayor, M. T. (2018). K-12 Program to Improve Quality of Education: Briones. Philippine News Agency . Retrieved February 3, 2021, from Available at: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1037617 .

Mora-Ruano, J. G., Heine, J.-H., and Gebhardt, M. (2019). Does Teacher Collaboration Improve Student Achievement? Analysis of the German PISA 2012 Sample. Front. Educ. 4 (85). doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00085

OECD, U.S. Department of Education (2019). PISA 2018: Insights and Interpretations. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA%202018%20Insights%20and%20Interpretations%20FINAL%20PDF.pdf .

Oxford Business Group (2021). The Philippine Government Works to Implement its K-12 Programme while Raising Educational Standards. Available at: https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/philippine-government-works-implement-its-k-12-programme-while-raising-educational-standards (Accessed May 9, 2020).

Pounder, D. G. (1999). Teacher Teams: Exploring Job Characteristics and Work-Related Outcomes of Work Group Enhancement. Educ. Adm. Q. 35, 317–348. doi:10.1177/00131619921968581

Punongbayan, J. C. (2019). Dismal Pisa Rankings: A Wake-Up Call for Filipinos. Rappler . Retrieved June 15, 2021, from Available at: https://www.rappler.com/voices/thought-leaders/246384-analysis-dismal-programme-international-student-assessment-rankings-wake-up-call-filipinos/ .

Puteh, S. N., Salam, K. A., and Jusoff, K. (2011). Using CBAM to Evaluate Teachers' Concerns in Science Literacy for Human Capital Development at the Preschool. World Appl. Sci. J. 14, 81–87.

Redondo, S. C., and Bueno, D. C. (2019). The Cognizance of the Basic Education Teachers on the K to 12 Program. Institutional Multidisciplinary Res. Dev. J. 2. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.27230.89924

Ronfeldt, M., Farmer, S. O., McQueen, K., and Grissom, J. A. (2015). Teacher Collaboration in Instructional Teams and Student Achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52 (3), 475–514. doi:10.3102/0002831215585562

Sarvi, J., Munger, F., and Pillay, H. (2015). Transitions K-12 Educ. Syst. Experiences five case countries .

Saunders, R. (2012). Assessment of Professional Development for Teachers in the Vocational Education and Training Sector : an Examination of the Concerns Based Adoption Model. Aust. J. Edu. 56 (2). doi:10.1177/000494411205600206

SEAMEO (2017). Guidebook to Education Systems and Reforms of Southeast Asia and China . Bangkok: Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization . [Publication]Available at: https://www.seameo.org/SEAMEOWeb2/images/stories/Publications/Centers_Pub/2017SEAMEOChina/GuidebooktoEducationSystemsandReforms.pdf .

Seashore Louis, K., Dretzke, B., and Wahlstrom, K. (2010). How Does Leadership Affect Student Achievement? Results from a National US Survey. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 21, 315–336. doi:10.1080/09243453.2010.486586

Shachar, H., and Shmuelevitz, H. (1997). Implementing Cooperative Learning, Teacher Collaboration and Teachers' Sense of Efficacy in Heterogeneous Junior High Schools. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 22 (1), 53–72. doi:10.1006/ceps.1997.0924

Tamar, L. R., and Atinc, M. (2017). Investigations into Using Data to Improve Learning: Philippines Case Study . Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution . Retrieved from Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/global-20170307-philippines-case-study.pdf .

Tibay, R. (2018). Lawmakers Start to Worry about Impact of K To12 Program on Ph Education System. Manila Bull. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from Available at: https://mb.com.ph/2018/05/26/lawmakers-start-to-worry-about-impact-of-k-to-12-program-on-ph-education-system/ .

Tuytens, M., and Devos, G. (2009). Teachers' Perception of the New Teacher Evaluation Policy: A Validity Study of the Policy Characteristics Scale. Teach. Teach. Edu. 25 (6), 924–930. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.014

Vilches, M. L. C. (2017). “Involving Teachers in the Change Process: One English Language Teacher's Account of Implementing Curricular Change in Philippine Basic Education,” in International Perspectives on Teachers Living with Curriculum Change . Editors M. Wedell,, and L. Grassick (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan ), 15–37. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-54309-7_2

Yea Lo, Yueh. (2018). English Teachers’ Concern on Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR): An Application of CBAM. JuKu: Jurnal Kurikulum & Pengajaran Asia Pasifik 6 (1), 46–58. ISSN 2289-3008. Retrieved from Available at: https://juku.um.edu.my/article/view/11174 .

Keywords: Philippine education, CBAM, teacher collaboration, level of concerns, educational policy

Citation: Magallanes K, Chung JY and Lee S (2022) The Philippine Teachers Concerns on Educational Reform Using Concern Based Adoption Model. Front. Educ. 7:763991. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.763991

Received: 24 August 2021; Accepted: 04 January 2022; Published: 23 May 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Magallanes, Chung and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jae Young Chung, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

- Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

The Philippines’ Basic Education Crisis

Recent features.

The Global AI Market No One Is Watching

Latin America and the China-US Space Race

September 24, 2024

Sponsored article: the challenge of cancer care in rural northeast india.

What’s in a Name? For Andaman and Nicobar Islands’ Capital, Everything.

How China Soured on Nepal

The Hidden Significance of China’s Aircraft Carrier Passage Near Japan’s Yonaguni Island

Will Indian Courts Tame Wikipedia?

The Asia-Pacific and the Israel-Lebanon Flashpoint: The UNIFIL Variable

Voters Show up in Record Numbers to Kick off Jammu and Kashmir Assembly Elections

What Could a Harris Administration Mean for Southeast Asia?

Central Asia: Facing 5 Assertive Presidents, Germany’s Scholz Gets Rebuffed on Ukraine

Envisioning the Asia-Pacific’s Feminist Future

Asean beat | society | southeast asia.

Out of the country’s 327,000-odd school buildings, less than a third are in good condition, according to government figures.

Three Filipino schoolgirls walking home from school on a muddy road in Port Barton, Palawan, the Philippines.

Several recent studies have pointed out the alarming deterioration of the quality of learning in the Philippines, but this was officially confirmed in the basic education report delivered by Vice President Sara Duterte on January 30. Duterte is concurrently serving as secretary to the Department of Education.

Addressing stakeholders with President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in attendance, Duterte highlighted the key issues that plague the country’s basic education system before announcing her department’s agenda for reform .

She echoed what previous surveys have indicated about the low academic proficiency of Filipino students. She also identified her department’s biggest concern. “The lack of school infrastructure and resources to support the ideal teaching process is the most pressing issue pounding the Philippine basic education,” she said.

She presented the latest government inventory which shows that out of 327,851 school buildings in the country, only 104,536 are in good condition. There are 100,072 school buildings that need minor repairs, 89,252 that require major repairs, and 21,727 that are set for condemnation.

She added that the procurement practices in the agency “had red flags that demanded immediate actions.” She shared initial findings in the ongoing review of the K-12 curriculum that underscored the failure of the 10-year-old program to deliver satisfactory results.

“The K-12 curriculum promised to produce graduates that are employable. That promise remains a promise,” she said.

Duterte criticized the heavy workload assigned to teachers as she pressed for an immediate review of the current setup in public schools. “This is a system that burdens them with backbreaking and time-consuming administrative tasks, a system that provides no adequate support and robs them of the opportunity to professionally grow and professionally teach, assist, and guide our learners,” she said.

She unveiled her education agenda themed “Matatag: Bansang Makabata, Batang Makabansa,” (Nation for children, children for the nation) and focused on curriculum reform, accelerated delivery of services, promoting the well-being of learners, and providing greater support to teachers.

Responding to the report, Marcos joined Duterte in acknowledging the government’s accountability to the nation’s young learners. “We have failed them,” he said. “We have to admit that. We have failed our children and let us not keep failing them anymore.” He promised to build better infrastructure by investing heavily in education.

He can cite as reference his government’s development plan , which was also released in January, about how the education crisis is linked to “decades of incapacity and suboptimal investment in education.”

Duterte’s admission about the dismal state of basic education was welcomed by some educators. Senators vowed to work with Marcos and Duterte in passing education reform measures. Opposition legislators urged Duterte to hear the views of school unions and student organizations whose appeals for better learning conditions are often dismissed by authorities as part of anti-government propaganda.

Meanwhile, the Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) noted that the report “failed to present today’s real extent and gravity of the learning crisis due to the lack of an evidence-based learning assessment conducted after the pandemic-induced school lockdowns.” The group was referring to the prolonged closure of schools under the government of President Rodrigo Duterte.

“Her father was president for six years and had not done any significant move to improve the lot of our mentors and of the education system. It is the government who have failed the teachers and our learners,” the group insisted.

It was also under the Duterte government when around 54 Lumad schools for indigenous peoples in Mindanao Island were either suspended or forced to shut down by authorities based on accusations that they were teaching rebellion.

The report also didn’t mention that some of the major questionable procurement transactions in the education department took place under the previous government.

The ACT criticized Duterte’s reform agenda because it features “general promises that lack specific action plans and definite targets.”

“No specific targets and timelines were presented to convincingly show that the agency will cut down the classroom shortage significantly,” it added.

Duterte said the agency will build 6,000 classrooms this year, which is quite small compared to the backlog identified in the report. There’s also no deadline for the electrification of around 1,562 schools that still do not have access to power.

Despite her impassioned plea to uplift the working conditions of educators, Duterte was castigated for being silent about the pending proposals to raise the salary grades of public school teachers.

ACT reminded officials to prove their political will in reversing the decline of Philippine education. “The call to reforming education should not be a grandstanding cry but a sincere pledge to rectify the mistakes and shortcomings of the past and the present,” it said.

This can be measured in at least two ways this year. First, Duterte’s willingness to file appropriate charges against erring officials involved in anomalous transactions under the previous administration. And second, Marcos’ commitment to substantially increase the funding for education.

Philippines Undertakes Major Review of School Curriculum

By mong palatino.

The First 100 Days of Philippine Vice President Sara Duterte

How Philippine Education Contributed to the Return of the Marcoses

By franz jan santos.

Philippine President Promises ‘No Special Treatment’ for Celebrity Preacher

By sebastian strangio.

By Cheng-kun Ma and K. Tristan Tang

4 Obstacles to India Joining the UN Security Council

By dhananjay tripathi.

Myanmar’s Silent Digital Crisis

By phyu sin shin thant.

South Korea’s Changing Position on Kim Jong Un’s Daughter

By isozaki atsuhito.

By Sarosh Nagar and Sergio Imparato

By Ana Soliz de Stange

By Siemens Healthineers

By Leesha K. Nair

- Philippines

The Philippines Still Hasn’t Fully Reopened Its Schools Because of COVID-19. What Is This Doing to Children?

I f 17-year-old Ruzel Delaroso needs to ask her teacher a question, she can’t simply raise her hand, much less fire off an email from the kitchen table. She has to leave the modest shack that her family calls home in Januiay, a farming town in the central Philippines, and head to an area of dense shrubbery, a 10-minute walk away. There, if she’s lucky, she can pick up a phone signal and finally ask about the math problem in the self-learning materials her mother picked up from school.

“We’re so used to our teachers always being around,” Delaroso tells TIME via the same temperamental phone connection. “But now it’s harder to communicate with them.”

Her school, Calmay National High School, is among the tens of thousands of Philippine public schools shuttered since March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Delaroso is one of 1.6 billion children affected by worldwide school closures, according to a UNESCO estimate.

But while other countries have taken the opportunity to resume in-person classes, the Philippines has lagged behind. After 20 months of pandemic prevention measures, amounting to one of the world’s longest lockdowns , only 5,000 students, in just over 100 public schools, have been allowed to go back to class in a two-month trial program—a tiny fraction of the 27 million public school students who enrolled this year. The Philippines must be one of a very few countries, if not the only country, to remain so reliant on distance learning. It has become a vast experiment in life without in-person schooling.

Read More: What It’s Like Being a Teacher During the COVID-19 Pandemic

“[Education secretary Leonor Briones] always reminds us that in the past when there were military sieges, or volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, typhoons, floods, learning continued,” says education undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio.

But has it this time? Educators fear that prolonged closure is having negative effects on students’ ability to learn, impacting their futures just a time when the country needs a young, well-educated workforce to resume the impressive economic growth it was enjoying before the pandemic hit.

Globally, COVID-19 will be impacting the mental health of children and young adolescents for years to come, UNICEF warns. School shutdowns have already been blamed for a rise in dropout rates and decreased literacy, and the World Bank estimates that the number of children aged 10 and below, from low- and middle-income countries, who cannot read simple text has risen from 53% prior to the pandemic to 70% today.

If the pilot resumption of classes passes without incident, there are hopes for a wider reopening of Philippine schools. But without it, there are fears of a lost generation .

How COVID-19 impacted Philippine education

From March 2020 to September 2021, UNICEF tallied 131 million pre-tertiary students from 11 countries who had been trying to learn at home for at least three quarters of the time that they would normally have been in school. Of that number, 66 million came from just two countries where face-to-face classes were almost completely nixed: Bangladesh and the Philippines. (Bangladesh reopened its schools in September.)

Amid the initial COVID-19 surge of March 2020—just weeks shy of the end of the academic year—the Philippines stopped in-person classes for its entire cohort of public education students, which then numbered some 24.9 million according to UNESCO. The start of the new school year in September also got pushed back, as President Rodrigo Duterte imposed a “no vaccine, no classes” policy.

When schooling finally resumed in October 2020, the education department’s solution was a blend of remote-learning options: online platforms, educational TV and radio, and printed modules. But social inequalities and the lack of resources at home to support these approaches have dealt a huge blow to many students and teachers.

A departmental report released in March 2021 found that 99% of public school students got passing marks for the first academic quarter of last year. But other surveys claim that students are being disadvantaged. Over 86% of the 1,299 students polled by the Movement for Safe, Equitable, Quality and Relevant Education said they learned less through the education department’s take-home modules—so did 66% of those using online learning and 74% using a blend of online learning and hard-copy material.

Read More: Angelina Jolie on Why We Can Let COVID-19 Derail Education

Even though she’s an academic topnotcher—getting a weighted grade average of 91 out of 100 last year—Delaroso also feels that remote learning is inferior.

At Delaroso’s high school, teacher Johnnalie Consumo, 25, has detected a lack of eagerness to study, with some parents even filling in worksheets on their child’s behalf—going by the evidence of the handwriting.

“They have a hard time forcing the kid to answer modules because the kid isn’t intimidated by their parents,” she tells TIME. “The way a teacher encourages is very different from how a parent would.”

Consumo sometimes visits the homes of under-performing students and finds that they are out doing farm work—harvesting sugar cane, say, or making charcoal—to augment a family income that has been slashed by a suffering economy and a rising unemployment rate . Exercise books have been turned in blank, she says. Or students appear to pass their modules, only for her to find that they copied the answers. The frustration is enormous.

“It’s hard on our part,” Consumo tells TIME, “because we really try our best.”

Poverty and education in the Philippines

Internet access is a huge challenge. In urban areas, instructors can give lessons over video conferencing platforms, or Facebook Live, but 52.6% of the Philippines’ 110 million people live in rural areas with unreliable connectivity. It doesn’t come cheap either: research from cybersecurity firm SurfShark found that the internet in the Philippines is among the least stable and slowest, yet the most expensive, of 79 countries surveyed.

Internet access assumes, of course, that the user has a device, but in the Philippines that’s not a given. Private polling firm Social Weather Stations found that just over 40% of students did not have any device to help them in distance learning. Of the rest, some 27% were using a device they already owned, and 10% were able to borrow one, but 12% had to buy one, with families spending an average of $172 per learner. To put it into perspective, that’s more than half the average monthly salary in the Philippines.

“Some of them don’t have cell phones,” says Marilyn Tomelden, a teacher in Quezon province, three hours away from the Philippine capital Manila, who first noticed the digital divide when many of her sixth graders were unable to comply with what she thought of as a fun homework assignment: submitting videos of themselves performing dance moves she had demonstrated in an earlier video.

“Because we’re in public school, we cannot demand that they buy phones,” Tomelden says. “They don’t have money to buy their own food, and they’re going to buy their own cell phone for learning? Which is more important to live—to eat or to study?”

Instructors need to be equipped with the right resources too. A study from the National Research Council of the Philippines found that many teachers have had to shell out their own money to support their students in remote learning.

Read More: The Long History of Vaccinating Kids in School

Government agencies do what they can to help. Earlier this year, the customs bureau donated phones and other gadgets it had confiscated to the education department for distribution to needy students. But it’s a drop in the ocean.

“It’s something that is beyond [our] capacity to address—the inequality in terms of availability of resources of learners, depending on the socioeconomic status of families,” says education undersecretary San Antonio.

Some students are so exhausted by the struggle to study remotely that they are calling for long breaks between modules. Many parents and pressure groups are going even further, demanding total academic suspension until a clearer post-pandemic education system is ironed out.

Congresswoman France Castro is a member of ACT Teachers Partylist, a political party representing the education sector. She says a complete freeze would cause more problems than it solves.

“Education is a right,” she tells TIME. “Whatever form it will be, whether blended learning or modular, it’s better to continue it than to stop.”

But in the meantime, with their workloads multiplied, it is students and teachers paying the price. Consumo, the teacher from Januiay, regularly stays up late completing the reams of new paperwork generated by the distance learning system.

“You won’t be able to sleep anymore, just thinking about the deadlines and the work that still needs to be done,” she says. “I cry over that.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- Iran, Trump, and the Third Assassination Plot

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- The Ordained Rabbi Who Bought a Porn Company

- Introducing the Democracy Defenders

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at [email protected]

ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty.

Established in 1966, it is owned by 69 members—49 from the region..

- Annual Reports

- Policies and Strategies

ORGANIZATION

- Board of Governors

- Board of Directors

- Departments and Country Offices

ACCOUNTABILITY

- Access to Information

- Accountability Mechanism

- ADB and Civil Society

- Anticorruption and Integrity

- Development Effectiveness

- Independent Evaluation

- Administrative Tribunal

- Ethics and Conduct

- Ombudsperson

Strategy 2030

Annual meetings, adb supports projects in developing member countries that create economic and development impact, delivered through both public and private sector operations, advisory services, and knowledge support..

ABOUT ADB PROJECTS

- Projects & Tenders

- Project Results and Case Studies

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

- Public Sector Financing

- Private Sector Financing

- Financing Partnerships

- Funds and Resources

- Economic Forecasts

- Publications and Documents

- Data and Statistics

- Asia Pacific Tax Hub

- Development Asia

- ADB Data Library

- Agriculture and Food Security

- Climate Change

- Digital Technology

- Environment

- Finance Sector

- Fragility and Vulnerability

- Gender Equality

- Markets Development and Public-Private Partnerships

- Regional Cooperation

- Social Development

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Urban Development

REGIONAL OFFICES

- European Representative Office

- Japanese Representative Office | 日本語

- North America Representative Office

LIAISON OFFICES

- Pacific Liaison and Coordination Office

- Pacific Subregional Office

- Singapore Office

SUBREGIONAL PROGRAMS

- Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA)

- Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program

- Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Program

- Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT)

- South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation (SASEC)

With employees from more than 60 countries, ADB is a place of real diversity.

Work with us to find fulfillment in sharing your knowledge and skills, and be a part of our vision in achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable asia and the pacific., careers and scholarships.

- What We Look For

- Career Opportunities

- Young Professionals Program

- Visiting Fellow Program

- Internship Program

- Scholarship Program

FOR INVESTORS

- Investor Relations | 日本語

- ADB Green and Blue Bonds

- ADB Theme Bonds

INFORMATION ON WORKING WITH ADB FOR...

- Consultants

- Contractors and Suppliers

- Governments

- Executing and Implementing Agencies

- Development Institutions

- Private Sector Partners

- Civil Society/Non-government Organizations

PROCUREMENT AND OUTREACH

- Operational Procurement

- Institutional Procurement

- Business Opportunities Outreach

Advancing the K-12 Reform from the Ground: A Case Study in the Philippines

Share this page.

This paper describes the implementation of the Certificate in Educational Studies in Leadership (CESL) in the Philippines as a professional development initiative delivered in a customized blended learning mode.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/WPS200105

The design principles of this promising pilot leverage on the use of technology, activation of communities of practice, and planning and implementation of context-specific transformational action projects targeted at education leaders. The authors contend that CESL fits within the leadership development ecology of the Philippine Department of Education and the National Educators Academy of the Philippines for the 21st century. As a transformative development program, CESL can be one of the many ways to jumpstart and sustain authentic education reforms.

- Introduction: The Philippine Context

- K-12 Reform and Education Leadership

- Certificate in Educational Studies in Leadership

- CESL: Professional Learning Development through Blended Learning

- CESL: Relevance, Collaboration, and a Future Focus

- Conclusion: Can CESL be Integrated into DepEd’s System

Additional Details

| Authors | |

| Type | |

| Series | |

| Subjects | |

| Countries | |

| Pages | |

| Dimensions | |

| SKU |

- More on education

- More on ADB’s work in the Philippines

Also in this Series

- Emerging Hydrogen Energy Technology and Global Momentum

- Proposed Life Cycle Approach for Promoting Climate Resilience and Carbon Neutrality: Case of the Road Subsector in Tajikistan

- Basic Tool Kit for Cybersecurity in Education Management Information Systems

- ADB funds and products

- Agriculture and natural resources

- Capacity development

- Climate change

- Finance sector development

- Gender equality

- Governance and public sector management

- Industry and trade

- Information and Communications Technology

- Private sector development

- Regional cooperation and integration

- Social development and protection

- Urban development

- Central and West Asia

- Southeast Asia

- The Pacific

- China, People's Republic of

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Micronesia, Federated States of

- Learning materials Guidelines, toolkits, and other "how-to" development resources

- Books Substantial publications assigned ISBNs

- Papers and Briefs ADB-researched working papers

- Conference Proceedings Papers or presentations at ADB and development events

- Policies, Strategies, and Plans Rules and strategies for ADB operations

- Board Documents Documents produced by, or submitted to, the ADB Board of Directors

- Financing Documents Describes funds and financing arrangements

- Reports Highlights of ADB's sector or thematic work

- Serials Magazines and journals exploring development issues

- Brochures and Flyers Brief topical policy issues, Country Fact sheets and statistics

- Statutory Reports and Official Records ADB records and annual reports

- Country Planning Documents Describes country operations or strategies in ADB members

- Contracts and Agreements Memoranda between ADB and other organizations

Subscribe to our monthly digest of latest ADB publications.

Follow adb publications on social media..

Impact of Policy Implementation on Education Quality: A Case Study on Philippines’ Low Ranking in International and Local Assessment Programs

- Updated as of 7:14 am April 3, 2023

Louie Benedict R. Ignacio The Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Letters, University of Santo Tomas

Andrea Gaile A. Cristobal The Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Letters, University of Santo Tomas

Paul Christian David The Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Letters, University of Santo Tomas

Corresponding Author: Paul Christian David, The Department of Political Science, Faculty of Arts and Letters, University of Santo Tomas, Espana, Manila Email : [email protected]

Recommended Citation: Ignacio, L. B., Cristobal, A., David, P., (2022). Impact of Policy Implementation on Education Quality: A Case Study on Philippines’ Low Ranking in International and Local Assessment Programs. Asian Journal on Perspectives in Education, 3(1), 41-54