Hamlet by William Shakespeare: Book Review, Summary and Analysis

Book: hamlet written by william shakespeare.

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, often shortened to Hamlet, is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Wikipedia

Who is Hamlet

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, is an idealist and perfectionist. The death of the father, the marriage of the mother to the uncle, and the ghost of the father telling Hamlet that he was killed by Claudius.

"Hamlet" Synopsis

"Hamlet", also known as "The Prince's Revenge", "Hamlet", "Macbeth", "King Lear" and "Othello" are called Shakespeare's "four tragedies". "Hamlet" is the longest play among Shakespeare's plays, and it is also the most prestigious play.

It has profound tragic significance and represents the highest achievement of Western Renaissance literature. The "to be or not to be" said by Hamlet in the play is even more classic among the classics.

Why Hamlet is a Masterpiece

"Hamlet" deserves to be a masterpiece, it can be a magical work, or it can be a work created by God. To put it simply, this work has been widely circulated in the world today, and it has been touched on in various fields of Western culture. If you want to learn Western culture, "Hamlet" is definitely a classic work.

For example, in "Hamlet" in the book, don't be attached to your mother. From the perspective of modern people, this kind of behavior may be more or less understandable, but when Shakespeare wrote this book, if he had such an idea, it was absolutely detached. of.

Reading the original work is the greatest respect for the author. Since Shakespeare was able to create such a work, his thoughts must surpass others and be more open.

What exactly does Hamlet want to reflect?

When Shakespeare wrote this book, he was in the Renaissance period. What he wanted to express was the rampant bourgeoisie and the chaotic and dark age in England at that time. Relics of history.

About the Author: William Shakespeare

At first, he worked as a horse guard for the theater and did chores in other houses, and later became an actor. Just play in the beginning. In 1593, Shakespeare's first long poem, Venus and Adonis, was published.

For more than 20 years from the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 17th century, Shakespeare started a successful career in London.

Excerpts from the original text: Hamlet

Introduction to the story of hamlet.

"Hamlet" describes the Danish prince Hamlet's revenge for his father. When the prince was studying in Germany, his father was killed by his younger brother Claudius. The murderer covered up the truth, usurped the throne, and married the king's wife; Hamlet worked hard to understand the truth in the play.

"Hamlet" is the longest play among all Shakespeare's plays, and it is also Shakespeare's most famous play. It has profound tragic significance, complex characters, and rich and perfect tragic art techniques, and represents the whole of Western Renaissance literature. highest achievement. Together with "Macbeth", "King Lear" and "Othello", they form Shakespeare's "four tragedies".

William Shakespeare was an English Renaissance dramatist and poet, a master of humanist literature in the European Renaissance, and one of the founders of modern European literature. He wrote a total of 37 plays, 154 sonnets, two long poems, and other poems.

What are the main contents of Hamlet?

" Hamlet " is a tragic work written by English playwright William Shakespeare between 1599 and 1602. The play tells that Uncle Claudius murdered Hamlet's father, usurped the throne, and married the king's widow Gertrude; Prince Hamlet avenged his uncle for his father.

That ghost was the ghost of Hamlet's father. They observed it for two consecutive nights. On the third night, they called Horatio and found the ghost. He was Hamlet's good friend, so he decided to call this ghost Tell Hamlet. On the morning of the fourth day, he told Hamlet about it, and Hamlet was so surprised that he also decided to go and have a look.

Makes everyone look crazy when they see him, and makes others think he is really crazy. At this time, she fell in love with Ophelia, the daughter of a flattering minister Polonius. To please the king, Polonius is unwilling to let Hamlet and Ophelia touch each other, so Hamlet is very angry and becomes crazier.

He kept thinking about these things, concentrating on how to avenge the king and finally found out that it was he who killed him. After the play in the queen's bedroom, when he was talking with the queen, Polonius was entrusted by the king to hide behind the curtain and eavesdrop on their conversation.

Polonez's daughter, Ophelia, went mad when she found out, sang songs without thinking at all, and finally committed suicide by jumping into the river. Her brother, Laertes, was furious when he came back from France and decided to kill Hamlet.

The queen also drank the poisoned wine originally given to Hamlet and died. Finally, Fortinbras, who came to Danmai, saw the tragedy, took advantage of the fire, and returned Denmark to his territory.

Why is it said that "action" is the most brilliant stroke in Hamlet's life?

In fact, this scene also reflects the characteristics of Hamlet's actions. "To be or not to be" seems to have two options on the surface, but Hamlet has no intention of accepting reality, giving up the mission of revenge, and living in the world.

The biggest feature of Hamlet's character is the delay, but Hamlet is in action in the sword fight. It seems contradictory, but it is in line with the logic of Hamlet's character. Because fighting swords was not a strategy he took on his own initiative, when he accepted the challenge, he completely had the mentality of letting fate arrange it.

It can be said that at the end of the tragedy, Hamlet finally overcomes the fear of death and bravely sends out a final blow to evil. He is finally destroyed by evil, but he uses his actions to tell the world that the spirit of humanism The brilliant brilliance of the spirit and ideal also makes this work have a distinct critical significance.

Please enable JavaScript

What enlightenment significance does Hamlet's tragedy have?

The significance of the tragedy of Hamlet's image lies in From a positive perspective, his struggle reflects the historical progress of the uncompromising struggle between the humanist thinkers of the Renaissance and the declining feudal forces and is the product of the inevitable requirement of historical development.

Hamlet Book Summary and Analysis

Hamlet's book review.

Hamlet (drawing sword) what! Which rat thief is it? It must be fatal, I will kill you. (Piercing the curtain with a sword) Polonius (behind) Ah! I'm dead! Ouch, queen! What have you done? I don't know Hamlet; isn't that the king? Queen, what reckless and cruel behavior! Hamlet's cruel behavior! Good mother, it's as bad as killing a king and marrying his brother. The queen killed a king! Hamlet Well, mother, that's exactly what I said. (See Polonius on the drape) Goodbye, you unlucky, careless, nosy fool! …… —— "Hamlet" Act 3, Act 4, Act 5, Act 1

Hamlet, you prayed wrongly. Please don't pinch my head and neck; because although I am not an irritable person, it is very dangerous for my fire to break out, so don't annoy me. Let go of your hand!

Hamlet, hey, I'm willing to fight him over this subject until my eyelids stop blinking.

Hamlet, I love Ophelia; the love of forty thousand brothers, combined, is not worth my love for her. What are you willing to do for her? ——In the first scene of the fifth act of "Hamlet"

Hamlet, you are a man, give me the glass! (Compete with Horasch for the glass) Let go! God, give it to me! (Overturning the wine glass in Horasch's hand) God, if no one can expose the truth of this matter, then how much my name will be harmed! If you ever loved me, Then please sacrifice the happiness of heaven for the time being, and stay in this cold world to bear the pain and tell the world my story. —— "Hamlet" Act 5, Scene 4,

Reading Notes

'ReadingAndThinking.com' content is reader-supported. "As an Amazon Associate, when you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.".

Related Post

Explore and find your next good read - Book Recommendations for specific interests.

Explore and find your next Book Summary for specific interests.

Explore and find Book Series for specific interests.

Recent Post

Book reviews, popular posts, 30 hilariously most inappropriate children's books (adults).

Welcome to an insightful journey through the ' 30 hilariously most inappropriate children's books (adults ) ,' which is based o...

25 Best Books to Attract Women and Get the Girl

Jean-christophe by romain rolland book review, summary, & analysis, 19 books from elon musk's reading list recommended for everyone.

Elon Musk has recommended a variety of books across different genres, including non-fiction, science fiction, and business. Curious about wh...

Books by Subject

Tiger Riding for Beginners

Bernie gourley: traveling poet-philosopher & aspiring puddle dancer.

BOOK REVIEW: Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Amazon.in page

Get Speechify to make any book an audiobook

This is probably Shakespeare’s most popular work. If it’s not, it has to be in the top three. One reason for its popularity relates to language. There’s probably a higher density of widely-quoted lines, and phrases that are part of common speech, in this play than in any other work of literature. From Polonius’s warnings to his son (e.g. “Neither a borrower nor a lender be”), to Hamlet’s soliloquized attempts to think through a course of action (“To be, or not to be: That is the question:”), to Hamlet’s wisdom in moments of lucidity (”There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” or “There is more in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than is dreamt of in your philosophy.”) to the many other quotes from various characters that appear across pop culture and everyday speech. “Methinks she doth protest too much,” “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” “Brevity is the soul of wit,” and “Sweets to the sweet” [or variations thereof] all derive from this play.

But quotability isn’t the sole basis for the play’s popularity. While it’s certainly not the most action-packed of Shakespeare’s plays, that is actually part of what makes it unique and makes its lead character relatable. Shakespeare’s works are full of tragedy resulting from rash conclusions that – in turn — result in ill-considered actions. How many times have we seen the case of a man who is too quick to believe his wife or girlfriend has been unfaithful, and – after the cataclysmic fallout – he then discovers that it was never true in the first place. Hamlet turns the convention on its head, showing us what can go wrong with a character who – in true scholarly fashion – is prone to paralysis by analysis. Hamlet is prone to drawn out contemplation that results in missed opportunities – not to mention, tragic neglect of his love interest, Ophelia. [Such over-analysis is exemplified by the famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy as Hamlet considers suicide.] It might seem like inaction would make for a boring play, but the tragedy unfolds never-the-less. [And in the instances in which there is fast-action, it proves flawed as when Hamlet mistakenly kills Polonius.]

Another element of the play’s success hinges on a technique for which Shakespeare was a pioneer and an early master, strategic ambiguity. We don’t know the degree to which Hamlet is insane versus pretending, regardless of hints in the form of moments of lucidity. At least until the final act, we don’t know the degree to which Hamlet’s mother is in on Claudius’s plotting. We also don’t know if Ophelia is a lunatic when she is handing out flowers, or if she’s cunningly delivering a masterful series of passive-aggressive bitch-slaps. Shakespeare is careful with his reveals, and sometimes chooses to not offer any at all.

As most people are at least vaguely acquainted with the story, I’ll offer only a brief description. [But if you don’t want the story spoiled any more than it has been, call it quits here.] Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, returns home from college. He’s bummed because, not only did his father recently die, but his mother has remarried his uncle. Hamlet might be able to cope with this apparent disrespect [arguably to him as well as his father because young Hamlet was next in line of succession], but then his father’s ghost appears to Hamlet. The ghost tells him that he (Hamlet’s father) was murdered by Claudius, and the ghost insists upon revenge. Hamlet doesn’t want to be punked by a malevolent spirit, so he has a group of actors modify their play so that it depicts the assassination as the ghost described it. When Claudius is shaken up by the scene and leaves the theater, Hamlet feels certain that the ghost spoke true. When Hamlet goes to visit his mother, he believes that Claudius [or a real rat] is spying on him and stabs out at a rustling curtain, but he actually kills Polonius (father to Hamlet’s love interest, Ophelia, and a guy who doesn’t deserve to die – despite being a bit of an irritating know-it-all.) Polonius’s killing triggers a sequence of events that ultimately results in Hamlet being sent to England, Ophelia committing suicide, and her brother, Laertes, coming home intent on getting revenge for Polonius’s murder.

Hamlet discovers that Claudius sent him off with a “Please kill this man” note, but Hamlet manages to replace the King’s order and escape. He returns to Denmark in time to happen upon Ophelia’s funeral. He’s distraught about Ophelia’s death, despite having been a complete jerk to the girl whenever he wasn’t completely ignoring her. Laertes is angry at Hamlet for killing Polonius and giving his sister a lethal case of heartbreak, and there is a tussle. This is broken up and an agreement is made to have a gentleman’s duel later. Unbeknownst to Hamlet, this is part of a plot engineered by Claudius and Laertes. [To be fair, Laertes doesn’t know what a treacherous villain Claudius is, and how much the King’s previous plot – killing Hamlet’s father – is the cause all the play’s unfortunate events – as opposed to them resulting from Hamlet being part crazy and part jackass.] Claudius and Laertes poison the tip of Laertes’ rapier, and Claudius doubles down by pouring some more poison into Hamlet’s cup [which Hamlet’s mother ultimately drinks, followed by forced consumption by Claudius at the hands of Hamlet.] In true tragic form, the end is an orgy of death.

This is a must read (or see) for everyone – both for the language and the complex and interesting characters.

View all my reviews

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare" data-content="https://berniegourley.com/2020/07/07/book-review-hamlet-by-william-shakespeare/" title="Share on Tumblr">Share on Tumblr

8 thoughts on “ BOOK REVIEW: Hamlet by William Shakespeare ”

AMAZING WORK!

Like Liked by 1 person

An insightful view of perhaps the finest play ever written. Loved it! 👍🖤

Pingback: BOOK REVIEW: Coriolanus by William Shakespeare | the !n(tro)verted yogi

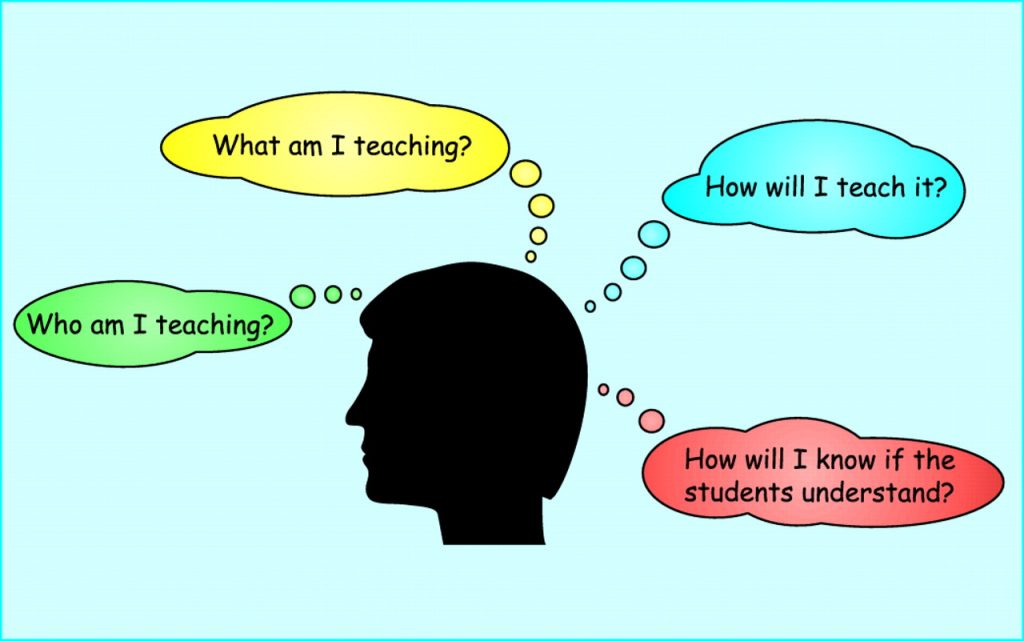

I studied Hamlet for A level English when I was sixteen – it had the most profound effect on me – at the time. A lot of the time i identifid with all his prevarications and hesitations. I spent a lot of time overthinking everything and making myself extremely misrable. but what held me up was the language. Shakespeare is incredibly profound. a real man of th epeole he appeals on every level. When I finally became an english teacher i could at last fulfil my passion for making shkaespeare accessible to all abilities. one of my best moment swas taking some pupils with learning difficulties to see a four hour production of King Lear at the Barbican Theatre with ian McKellen, and listening to them exclaim with recognition as they heard the lines they had been studying and saw the scenes they had been imagining. I loved teaching Shakespeare and proving to young people he was still fun and interesting and to use a phrase I dislike – relevant!

thanks for the comment

Excuse all the typos – it won’t let me edit this!

No problem.

Definitely the best of Shakespeare’s plays. Superficially, it is a story of revenge. On a deeper level, it shows the impact violent acts have on those associated with the victims. One criminal but six deaths…

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- How did Shakespeare die?

- Why is Shakespeare still important today?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Lit2Go - "Hamlet"

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology - The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

- Internet Archive - Shakespeare's Hamlet

- Literary Devices - Hamlet

- Royal Shakespeare Company - "Hamlet"

- Washington State University - Hamlet

- Hartford Stage - A Synopsis of Hamlet

- Folger Shakespeare Library - "Hamlet"

- Hamlet - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Hamlet , tragedy in five acts by William Shakespeare , written about 1599–1601 and published in a quarto edition in 1603 from an unauthorized text, with reference to an earlier play. The First Folio version was taken from a second quarto of 1604 that was based on Shakespeare’s own papers with some annotations by the bookkeeper.

Shakespeare’s telling of the story of Prince Hamlet was derived from several sources, notably from Books III and IV of Saxo Grammaticus ’s 12th-century Gesta Danorum and from volume 5 (1570) of Histoires tragiques , a free translation of Saxo by François de Belleforest. The play was evidently preceded by another play of Hamlet (now lost), usually referred to as the Ur-Hamlet , of which Thomas Kyd is a conjectured author.

As Shakespeare’s play opens, Hamlet is mourning his father, who has been killed, and lamenting the behaviour of his mother, Gertrude , who married his uncle Claudius within a month of his father’s death. The ghost of his father appears to Hamlet, informs him that he was poisoned by Claudius, and commands Hamlet to avenge his death. Though instantly galvanized by the ghost’s command, Hamlet decides on further reflection to seek evidence in corroboration of the ghostly visitation, since, he knows, the Devil can assume a pleasing shape and can easily mislead a person whose mind is perturbed by intense grief. Hamlet adopts a guise of melancholic and mad behaviour as a way of deceiving Claudius and others at court—a guise made all the easier by the fact that Hamlet is genuinely melancholic.

Hamlet’s dearest friend, Horatio, agrees with him that Claudius has unambiguously confirmed his guilt. Driven by a guilty conscience , Claudius attempts to ascertain the cause of Hamlet’s odd behaviour by hiring Hamlet’s onetime friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on him. Hamlet quickly sees through the scheme and begins to act the part of a madman in front of them. To the pompous old courtier Polonius , it appears that Hamlet is lovesick over Polonius’s daughter Ophelia . Despite Ophelia’s loyalty to him, Hamlet thinks that she, like everyone else, is turning against him; he feigns madness with her also and treats her cruelly as if she were representative, like his own mother, of her “treacherous” sex.

Hamlet contrives a plan to test the ghost’s accusation. With a group of visiting actors, Hamlet arranges the performance of a story representing circumstances similar to those described by the ghost, under which Claudius poisoned Hamlet’s father. When the play is presented as planned, the performance clearly unnerves Claudius.

Moving swiftly in the wake of the actors’ performance, Hamlet confronts his mother in her chambers with her culpable loyalty to Claudius. When he hears a man’s voice behind the curtains, Hamlet stabs the person he understandably assumes to be Claudius. The victim, however, is Polonius, who has been eavesdropping in an attempt to find out more about Hamlet’s erratic behaviour. This act of violence persuades Claudius that his own life is in danger. He sends Hamlet to England escorted by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern , with secret orders that Hamlet be executed by the king of England. When Hamlet discovers the orders, he alters them to make his two friends the victims instead.

Upon his return to Denmark, Hamlet hears that Ophelia is dead of a suspected suicide (though more probably as a consequence of her having gone mad over her father’s sudden death) and that her brother Laertes seeks to avenge Polonius’s murder. Claudius is only too eager to arrange the duel. Carnage ensues. Hamlet dies of a wound inflicted by a sword that Claudius and Laertes have conspired to tip with poison; in the scuffle, Hamlet realizes what has happened and forces Laertes to exchange swords with him, so that Laertes too dies—as he admits, justly killed by his own treachery. Gertrude, also present at the duel, drinks from the cup of poison that Claudius has had placed near Hamlet to ensure his death. Before Hamlet himself dies, he manages to stab Claudius and to entrust the clearing of his honour to his friend Horatio.

For a discussion of this play within the context of Shakespeare’s entire corpus, see William Shakespeare: Shakespeare’s plays and poems .

William Shakespeare | 4.36 | 724,830 ratings and reviews

Ranked #1 in Drama , Ranked #1 in Theater — see more rankings .

Reviews and Recommendations

We've comprehensively compiled reviews of Hamlet from the world's leading experts.

Ryan Holiday Author Philosophy runs through this play–all sorts of great lines. There are gems like “..for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” which I used in my last book and “Beware of entrance to a quarrel; but, being in, bear it, that the opposed may beware of thee.” was a favorite of Sherman. (Source)

Tim Lott I love the speech when Hamlet’s uncle Claudius admits to being inflicted with the primal eldest curse for killing his brother, and begs on his knees for forgiveness for this ultimate violation of the law of nature. (Source)

Rankings by Category

Hamlet is ranked in the following categories:

- #94 in 10th Grade

- #33 in 11th Grade

- #4 in 12th Grade

- #92 in 15-Year-Old

- #33 in 16-Year-Old

- #4 in 17-Year-Old

- #4 in 18-Year-Old

- #25 in Academia

- #45 in Acting

- #23 in Archives

- #81 in Betrayal

- #32 in Broadway

- #54 in Bucket List

- #59 in Character

- #75 in Character Development

- #12 in Class

- #37 in Classic

- #28 in Classical

- #55 in Death

- #52 in Dramatic

- #23 in English Vocabulary

- #18 in English Writer

- #33 in Existential

- #57 in Existentialism

- #12 in Family Law

- #71 in Ghost

- #79 in Ghost Story

- #59 in Gilmore Girls

- #10 in High School

- #12 in High School Reading

- #77 in Human Nature

- #91 in Influential

- #93 in Ireland

- #71 in Literary

- #38 in Literature

- #20 in Murder

- #42 in Period

- #55 in Poster

- #19 in Procrastination

- #70 in Project Gutenberg

- #35 in Public Domain

- #2 in Renaissance

- #2 in Revenge

- #86 in Royalty

- #14 in Screenplay

- #2 in Shakespeare

- #70 in Soul

- #33 in Suicide

- #87 in Top Ten

- #3 in University

- #67 in Used

- #24 in Vocabulary

Similar Books

If you like Hamlet, check out these similar top-rated books:

Learn: What makes Shortform summaries the best in the world?

A Summary and Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

To attempt an analysis of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in a single blog post: surely a foolhardy objective if ever there was one. So here we’ll try to focus on some of the key points of Hamlet and analyse their significance, homing in on some of the most interesting as well as some of the most notable aspects of Shakespeare’s play.

Hamlet is a long play, but it’s also a fascinating one, with a ghost, murder, mistaken identity, family drama, poison, pirates, duels, skulls, and even a fight in an open grave. What more could one ask for?

Hamlet is a long play – at just over 30,000 words, the longest Shakespeare wrote – so condensing the plot of this play into a shortish plot summary is going to prove tricky. Still, we’ll do our best. Here, then, is a very brief summary of the plot of Hamlet , perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy.

The play begins on the battlements at Elsinore Castle in Denmark one night. The ghost of the former king, Hamlet, is seen, but refuses to speak to any of the soldiers on guard duty. At the royal court, Prince Hamlet (the dead king’s son) shows disgust at his uncle, Claudius, who is king, having taken the throne after Hamlet’s father, Claudius’ brother, died.

Hamlet also resents his mother, Gertrude – who, not long after Hamlet Senior’s death, remarried … to Claudius. Claudius gives the young man Laertes, the son of the influential courtier Polonius, leave to return to France to study there. At the same time, Claudius and Gertrude entreat Hamlet not to return to his studies in Germany, at the University of Wittenberg. Hamlet agrees to remain at court.

Laertes leaves Denmark for France, bidding his sister Ophelia farewell. He tells her not to take Hamlet’s expressions of affection too seriously, because – even if Hamlet is keen on her – he is not free to marry whom he wishes, being a prince. Polonius turns up and gives his son some advice before Laertes leaves; Polonius then reiterates Laertes’ advice to Ophelia about Hamlet, commanding his daughter to stay away from Hamlet.

Hamlet’s friend Horatio tells Hamlet about the Ghost, and Hamlet visits the battlements with his friend. The Ghost reappears – and this time, he speaks to Hamlet in private, telling him that he is the prince’s dead father and that he was murdered (with poison in the ear, while he lay asleep in his orchard) by none other than Claudius, his own brother.

He tells his son to avenge his murder by killing Claudius, the man who murdered the king and seized his throne for himself. However, he tells Hamlet not to kill Gertrude but to ‘leave her to heaven’ (i.e. God’s judgment). Hamlet swears Horatio and the guards to secrecy about the Ghost.

Hamlet has vowed to avenge his father’s murder, but he has doubts over the truth of what he’s seen. Was the ghost really his father? Might it not have been some demon, sent to trick him into committing murder? Claudius may disgust Hamlet already, but murdering his uncle just because he married Hamlet’s mum seems a little extreme.

But if Claudius did murder Hamlet’s father, then Hamlet will gladly avenge him. But how can Hamlet ascertain whether the Ghost really was his father, and that the murder story is true? To buy himself some time, Hamlet tells Horatio that he has decided to ‘put an antic disposition on’: i.e., to pretend to be mad, so Claudius won’t question his scheming behaviour because he’ll simply believe the prince is just being eccentric in general.

Polonius sends Reynaldo off to spy on his son, Laertes, in France. His daughter Ophelia approaches him, distressed, to report Hamlet’s strange behaviour in her presence. Polonius is certain that Hamlet’s odd behaviour springs from his love for Ophelia, so he rushes off to tell the King and Queen, Claudius and Gertrude, about it.

Claudius and Gertrude welcome Hamlet’s childhood friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to court and charge them with talking to Hamlet to try to find out what’s the matter with him. Polonius arrives and tells the King and Queen that Hamlet is mad with love for Ophelia, and produces a love letter Hamlet wrote to her as proof.

As Hamlet approaches, Polonius hatches a plan: he will talk to Hamlet while the King and Queen listen in secret from behind an arras (tapestry). Sure enough, Hamlet talks in riddles to Polonius, who then leaves, convinced he is right about the cause of Hamlet’s madness. Hamlet talks to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who tell him that the actors are on their way to court.

Hamlet is suspicious that his friends were sent for by Claudius and Gertrude to spy on him (as indeed they were); he confides to his old friends that he is not necessarily really mad; he implies he’s putting it on and still has his wits about him. The actors arrive, and Polonius returns, prompting Hamlet to start answering him with cryptic responses again, to keep up the act of being mad.

To determine Claudius’ guilt, Hamlet turns detective and devises a plan to try to get Claudius to reveal his crime, inadvertently. Hamlet persuades the actors to perform a play, The Murder of Gonzago , including some specially inserted lines he has written – in which a brother murders the king and marries the king’s widow.

Hamlet’s thinking is that, when Claudius witnesses his own crime enacted before him on the stage, he will be so shocked and overcome with guilt that his reaction will reveal that he’s the king’s murderer.

Claudius and Gertrude ask Rosencrantz and Guildenstern what they made of Hamlet’s behaviour, and then the King and Queen, along with Polonius, hide so they can observe Hamlet talking with Ophelia. At one point, in an aside, Claudius talks of his ‘conscience’, providing the audience with the clearest sign that he is indeed guilty of murdering Old Hamlet.

This is significant because one of the main reasons Hamlet is being cautious about exacting revenge is that he’s having doubts about whether the Ghost was really his father or not (and therefore whether it spoke truth to him). But we, the audience, know that Claudius almost certainly is guilty.

After he has meditated aloud about the afterlife, suicide, and the ways in which thinking deeply about things can make one less prompt to act (the famous ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy ), Hamlet speaks with Ophelia. He tells her he never loved her, and orders her to go to a nunnery because women do nothing but breed men who are sinners.

Ophelia is convinced Hamlet is mad for love, but Claudius believes something else is driving Hamlet’s behaviour, and resolves to send Hamlet to England, ostensibly on a diplomatic mission to get the tribute (payment) England owes Denmark.

Sure enough, Claudius responds to the performance of The Murder of Gonzago (or, as Hamlet calls this play-within-a-play, The Mousetrap ) by exclaiming and then walking out, and in doing so he convinces Hamlet that he is indeed guilty and the Ghost is right.

Now Hamlet can proceed with his plan to murder him. However, after the play, he catches Claudius at prayer, and doesn’t want to murder him as he prays because, if Claudius killed while speaking to God, he will be sent straight to heaven, regardless of his sins.

So instead, Hamlet visits Gertrude, his mother, in her chamber, and denounces her for marrying Claudius so soon after Old Hamlet’s death. The Ghost appears (visible only to Hamlet: Gertrude believes her son to be mad and that the Ghost is ‘the very coinage of [his] brain’), and spurs Hamlet on.

Hearing a sound behind the arras or tapestry, Hamlet lashes out with his sword, stabbing the figure behind, believing it to be Claudius. Unbeknownst to Hamlet, it is Polonius, having concealed himself there to spy on the prince. Polonius dies.

Claudius asks Hamlet where Polonius is, and Hamlet jokes about where he’s hid the body. Claudius dispatches Hamlet to England – ostensibly on a diplomatic mission, but in reality the King has arranged to have Hamlet murdered when he arrives in England. However, Hamlet realises this, escapes, has Rosencrantz and Guildenstern killed, and returns to Denmark.

Laertes returns from France, thinking Claudius was responsible for Polonius’ death. Claudius puts him right, and arranges for Laertes to fight Hamlet using a poisoned sword, with a chalice full of poisoned wine prepared for Hamlet should the sword fail.

As they are plotting, Gertrude comes in with the news that Polonius’ death has precipitated Ophelia’s slide into madness and, now, her suicide: Ophelia has drowned herself.

Laertes and Hamlet fight in Ophelia’s open grave, and then Hamlet challenges Laertes to a duel at court. Unbeknown to Hamlet, and as agreed with Claudius earlier on, Laertes will fight with a poisoned sword.

However, during the confusion of the duel, Hamlet and Laertes end up switching swords so both men are mortally wounded by the poisoned blade. Gertrude, in making a toast to her son and being unaware that the chalice of wine is poisoned, drinks the deadly wine.

Laertes, as he lies dying, confesses to Hamlet that Claudius hatched the plan involving the poisoned sword and wine, and Hamlet stabs Claudius with the poisoned sword, forcing him to drink the wine for good measure too – thus finally avenging his father’s murder. Hamlet dies, giving Fortinbras, the Prince of Norway, his dying vote as the new ruler of Denmark. Fortinbras arrives to take control of Denmark now the Danish royal family has been wiped out, and Horatio prepares to tell him the whole sorry tale.

Analysis of the play’s sources – and their significance

Although it’s often assumed that there must be some link between Shakespeare’s son Hamnet (who died aged 11, in 1596) and the playwright’s decision to write a play called Hamlet , it may in fact be nothing more than coincidence: Hamnet was a relatively common name at the time (Shakespeare had in fact named his son after a neighbour), he didn’t write Hamlet until a few years later, and there had already been at least one play about a character called Hamlet performed on the London stage some years earlier.

None of this rules out the idea that Shakespeare was transmuting personal grief over the death of Hamnet into universal art through writing (or, more accurately, rewriting) Hamlet , but it does need to be borne in mind when advancing a biographical analysis of Shakespeare’s greatest play.

This earlier play called Hamlet , which is referred to in letters and records from the time, was probably not written by Shakespeare but by one of his great forerunners, Thomas Kyd, master of the English revenge tragedy, whose The Spanish Tragedy had had audiences on the edge of their seats in the late 1580s. Unfortunately, no copy of this proto- Hamlet has survived – and we cannot be sure that Kyd was definitely the author (although he is the most likely candidate).

Most of Shakespeare’s plays are based on earlier stories or historical chronicles, and many are even based on earlier play-texts, which Shakespeare used as the basis for his own work. Indeed, very few of Shakespeare’s plays have no traceable source. But for some, in the case of Hamlet the relationship between Shakespeare’s play and the source-text is a problematic one.

The modernist poet T. S. Eliot argued in an essay of 1919 that Shakespeare’s Hamlet was ‘an artistic failure’ because the Bard was working with someone else’s material but attempting to do something too different with the relationship between Hamlet and his mother, Gertrude.

Whether we side with Empson or Eliot or with neither, the fact is that this earlier, sadly lost version of the ‘play about Hamlet’ wasn’t itself the origin of the Hamlet story, which is instead found in a thirteenth-century chronicle written by Saxo Grammaticus. In this chronicle, Hamlet is ‘Amleth’ and is only a little boy – and it’s common knowledge that his uncle has killed his father.

Because Danish tradition expects the son to avenge his father’s death, the uncle starts to keep a close eye on little Amleth, waiting for the boy to strike in revenge. To avert suspicion and make his uncle believe that he, little Amleth, has no plans to seek revenge, Amleth pretends to be mad – the ‘antic disposition’ which Shakespeare’s Hamlet will also put on.

Because the ‘antic disposition’ no longer makes as much sense to the plot in Shakespeare’s version – why would Hamlet’s uncle have to watch his back when he murdered Hamlet’s father in secret and Hamlet surely (at least according to Claudius) has no idea that he’s the murderer? – Hamlet becomes a more complex and interesting character than he had been in the source material.

There is not as clear a reason for Hamlet to ‘put an antic disposition on’ as there had been in the source material, where pretending to be slow-witted or mad could save young Amleth’s life.

The textual variants of Hamlet

There’s more than one Hamlet . The play we read depends very much on the edition we read, since the play has been edited in a number of different ways. The problem is that the play survives in three very different versions: the First Quarto printed in 1603 (the so-called ‘Bad’ Quarto), the Second Quarto from a year later, and the version which appeared in the First Folio in 1623.

Q1 – the First or ‘Bad’ Quarto – is well-named. It was most probably a pirated edition of Shakespeare’s text, perhaps hastily written down from the (rather faulty) memory of a theatregoer or perhaps even one of the actors.

To give you a sense of just how bad the Bad Quarto was, in Q1 the play’s most famous line, ‘To be or not to be: that is the question’, which begins his famous soliloquy in which he muses on the point of life and contemplates suicide, is rendered quite differently – as ‘To be or not to be, I there’s the point’.

It also appears at a different point in the play, just after Polonius (who is called ‘Corambis’) in this version – has hatched the plot to arrange a meeting between Hamlet and Polonius’ (sorry, Corambis’) daughter, Ophelia.

What does Hamlet the play actually mean ?

What is Hamlet telling us – about revenge, about mortality and the afterlife, or about thinking versus taking action about something? The play is ambivalent about all these things: deliberately, thanks to Shakespeare’s deft use of Hamlet’s own soliloquies (which often see him thrashing out two sides of a debate by talking to himself) and the clever use of doubling in the play.

Revenge is supposed to be left to God (‘Vengeance is mine,’ saith the Lord), but both Hamlet the play and Hamlet the character imply that it’s expected in Danish society of the time that the son would take vengeance into his own hands and avenge his murdered father: he is ‘Prompted to my revenge by heaven and hell’, as he says in his soliloquy at the end of II.2.

Christopher Ricks, the noted literary critic, has talked about how many great works of literature are about exploring the tension between two competing moral or pragmatic principles. Perhaps the two contradictory principles which we most clearly see in tension in Hamlet are the two axioms ‘look before you leap’ and ‘he who hesitates is lost’.

If Hamlet had been less a thinker and more a man of action, he would have made a snap judgment regarding Claudius’ guilt and then either taken revenge or resolved to leave it up to God.

But if he’d been wrong, he would have condemned an innocent man to death. However, if he’d been right, he would have spared everyone else who gets dragged into his quest for vengeance and destroyed along the way: Polonius (killed in error by Hamlet), Ophelia (killed by her own hand, but in response to her father’s death at Hamlet’s hands), Laertes (killed trying to avenge Polonius’ murder), and even – against the express wishes and commands of the Ghost himself – Hamlet’s own mother, who only drinks the poisoned wine by accident because she wants to wish her son good luck in the duel he’s fighting with Laertes.

This habit of Hamlet’s, his tendency to think things over, is both one of his most appealingly humane qualities, and yet also, in many ways, his undoing – and, ultimately, the end of the whole royal house of Denmark, since Fortinbras can come in and reclaim the land that was taken from his father by Old Hamlet all those years ago.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

4 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet”

- Pingback: Hamlet: A Short Plot Summary of Shakespeare’s Play – Interesting Literature

- Pingback: A Short Analysis of Shakespeare’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy from Hamlet – Interesting Literature

- Pingback: A Short Analysis of T. S. Eliot’s ‘Hamlet and his Problems’ – Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Seven of the Best Speeches from Shakespeare Plays – Interesting Literature

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

100 of the Greatest Books Read and Reviewed

100 of the World's Greatest books – classics that demand attention and have a lot to say to us today. This is a quest to read and review that top 100 classics, however long that journey may be!

Hamlet – William Shakespeare (Review)

Classic literature lists generally include a sprinkling of plays. Obviously any list of seminal works is going to include Hamlet, commonly regarded as Shakespeare’s greatest work. Now, I am always conflicted when I read plays. There is no doubt that one gets a lot from the text itself, but I always feel that the language is designed to be spoken and given life by actors on a stage, therefore reading those words loses something.

However, there is great enjoyment to be had reading this play. In addition to the unfolding plot, the edition I read came from my high school kids’ english class, therefore there were detailed notes including translations of the highly Shakespearian words from which the narrative is obviously compiled. This is often helpful for the most obscure and obsolete words although it tends to disrupt the rhythm of reading.

Obviously this tragedy is a well known story and, indeed, a theme that resonates throughout literature – revenge. In common with most such themes the reader is initially sympathetic to the main protagonist and shares some of the outrage that leads them to swear revenge on the perpetrators. However, as the quest continues, the character becomes more and more obsessive and, as a result, much less likable. Hamlet himself isn’t a particularly sympathetic character to me. His treatment of Ophelia is harsh and his determination to avenge his father (driven by the latter ghost) leads him to his own, and pretty much everyone else’s destruction.

Obviously this is a great play and the theme, whilst not original to Shakespeare of course, is extremely well developed here. One is familiar with the approach but since this is written before such other famous revenge driven plots such as “The Count of Monte Cristo”, it represents one of the earliest explorations of this damaging quest.

I haven’t seen Hamlet on stage for decades and would like to reacquaint myself with the live performance. There is so much in Shakespeare that has entered the English lexicon and one is not always aware of that until it becomes apparent in the text. I love coming across such phrases in their original context.

Hello! I'm Sandra. I'm here to inspire you in your self-help journey!

Sandra's Shelf

Self-Help & Books

Book Reviews · August 6, 2021

Book Review: Hamlet by William Shakespeare

This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my links, at no extra cost to you. Please read my full disclosure for more information.

“Hamlet” by William Shakespeare is truly a play everyone must-read at least once. Although it is not my personal favourite of Shakespeare but I highly enjoyed it!

- Date finished: February 26th, 2017

- Format: Paperback

- Language read in: English

- Series: Standalone

- Genre: Classics | Play | Drama

Buy “Hamlet” Amazon | Indigo | Book Depository

“Hamlet” follows the story of the young prince of Denmark – Hamlet – as he seeks revenge for the murder of his father. However, things are not always as they seem and the young prince’s life is in danger!

I was very excited to read Hamlet for the first time but I was, unfortunately, let down after the first act.

In my opinion, this play is mostly interesting due to its revenge plots and its play-within-play plot. Even these two interesting plot points weren’t sufficient enough to grasp my interest.

Admittedly, Hamlet is pretty clever. Leaving the readers unsure if he’s mad or just acting. Also, it was cheap for him to use the appeal to madness to justify his actions.

For those reasons, I don’t like Hamlet the hero much. I neither liked the other characters. Their actions, speeches, and interjections weren’t marking compared to other plays.

Furthermore, I don’t understand the Hamlet hype. The universally known “To Be or Not To Be” speech is surely the highlight due to its ambiguity and the lack of answer it proposes to its question.

I might not have liked the play as much but I liked the ending. All the characters annoyed me so much I wasn’t even upset, but relieved, that they were all gone. They were all treacherous, merciless, and hypocritical. I was like BYE.

Overall, Hamlet still remains a must-read.

“Doubt thou the stars are fire; Doubt that the sun doth move; Doubt truth to be a liar; But never doubt I love.”

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

Get on the List

You’ll also love.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Book Review: On Beauty by Zadie Smith

Popular posts.

Become an Insider

Join the list for exclusive content, resources, & freebies.

I'm Sandra. I hope to help you in your journey one post and one book at a time!

Disclaimers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

THIS WEBSITE IS A PARTICIPANT IN THE AMAZON SERVICES LLC ASSOCIATES PROGRAM, AN AFFILIATE ADVERTISING PROGRAM DESIGNED TO PROVIDE A MEANS FOR SITES TO EARN ADVERTISING FEES BY ADVERTISING AND LINKING TO AMAZON.COM.

Latest on Instagram

Copyright © 2024 Sandra's Shelf · Theme by 17th Avenue

- First Folio

- Third Folio

- Venus & Adonis

- A Lover's Complaint

- The Rape of Lucrece

- The Passionate Pilgrim

- The Phoenix & Turtle

- To the Queen

- Discussion Forum

- Separator 2

- All Reviews

- Theatre Reviews

- Film Reviews

- Book Reviews

- Features & Interviews

- Compare App Editions

- Student Use

- Teacher Use

- Actor/Director Use

- App Bookmarks and Notes

- ShakespeareTV App Overview

- Shakespeare App FAQs

- Soliloquy App FAQs

- Create Ticket

- All Historical Documents

- Editions of the Complete Works

- First Folio Editions

- Historical Reference Documents

- Falstaff Awards 2022

- Falstaff Awards 2021

- Falstaff Awards 2020

- Falstaff Awards 2019

- Falstaff Awards 2018

- Falstaff Awards 2017

- Falstaff Awards 2016

- Falstaff Awards 2015

- Falstaff Awards 2014

- Falstaff Awards 2013

- Falstaff Awards 2012

- Falstaff Awards 2011

- Falstaff Awards 2010

- Falstaff Awards 2009

- Falstaff Awards 2008

- Falstaff Awards 2007

- How to Submit a Work

- Play Chronology

- Scansion Overview

- Poetry Glossary

- Play Lengths

- Biggest Roles

- Complete Shakespeare Character List

- Monologues (Male)

- Monologues (Female)

- Overdone Monologues

- Scene Study (M+F)

- Scene Study (M+M)

- Scene Study (F+F)

- Shakespeare's Biography

- Shakespeare's Players

- Elizabethan Theatres

- About PlayShakespeare.com

- PlayShakespeare.com Team

- Text Sources

- Open Source

- The Tamer Tamed

- Sonnet Documents

- Follow us on Twitter

- Like us on Facebook

- Register for an account

- I forgot my username

- I forgot my password

William Shakespeare

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

| . Read our . |

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on William Shakespeare's Hamlet . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

Hamlet: Introduction

Hamlet: plot summary, hamlet: detailed summary & analysis, hamlet: themes, hamlet: quotes, hamlet: characters, hamlet: symbols, hamlet: literary devices, hamlet: quizzes, hamlet: theme wheel, brief biography of william shakespeare.

Historical Context of Hamlet

Other books related to hamlet.

- Full Title: The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

- When Written: Likely between 1599 and 1602

- Where Written: Stratford-upon-Avon or London, England

- When Published: First Quarto printed 1603; Second Quarto printed 1604; First Folio printed 1623

- Literary Period: Renaissance

- Genre: Tragic play; revenge play

- Setting: Elsinore Castle, Denmark, during the late Middle Ages

- Climax: After seeing Claudius’s emotional reaction to a play Hamlet has had staged in order to make Claudius face a fictionalized version of his own murder plot against the former king, Hamlet resolves to kill the Claudius without guilt.

- Antagonist: Claudius

- Point of View: Dramatic

Extra Credit for Hamlet

The Role of a Lifetime. The role of Hamlet is often considered one of the most challenging theatrical roles ever written, and has been widely interpreted on stage and screen by famous actors throughout history. Shakespeare is rumored to have originally written the role for John Burbage, one of the most well-known actors of the Elizabethan era. Since Shakespeare’s time, actors John Barrymore, Laurence Olivier, Ian McKellen, Jude Law, Kenneth Branagh, and Ethan Hawke are just a few actors who have tried their hand at playing the Dane. When Daniel Day-Lewis took to the stage as Hamlet in London in 1989, he left the stage mid-performance one night after reportedly seeing the ghost of his real father, the poet Cecil Day-Lewis, and has not acted in a single live theater production since.

Shakespeare or Not? There are some who believe Shakespeare did not actually write many—or any—of the plays attributed to him. The most common “Anti-Stratfordian” theory is that Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, wrote the plays and used Shakespeare as a front man, as aristocrats were not supposed to write plays. Others claim Shakespeare’s contemporaries such as Thomas Kyd or Christopher Marlowe may have authored his works. Most contemporary scholarship, however, supports the idea that the Bard really did compose the numerous plays and poems which have established him, in the eyes of many, as the greatest writer in history.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 25, 2020 • ( 2 )

With Shakespeare the dramatic resolution conveys us, beyond the man-made sphere of poetic justice, toward the ever-receding horizons of cosmic irony. This is peculiarly the case with Hamlet , for the same reasons that it excites such intensive empathy from actors and readers, critics and writers alike. There may be other Shakespearean characters who are just as memorable, and other plots which are no less impressive; but nowhere else has the outlook of the individual in a dilemma been so profoundly realized; and a dilemma, by definition, is an all but unresolvable choice between evils. Rather than with calculation or casuistry, it should be met with virtue or readiness; sooner or later it will have to be grasped by one or the other of its horns. These, in their broadest terms, have been—for Hamlet, as we interpret him—the problem of what to believe and the problem of how to act.

—Harry Levin, The Question of Hamlet

Hamlet is almost certainly the world’s most famous play, featuring drama’s and literature’s most fascinating and complex character. The many-sided Hamlet—son, lover, intellectual, prince, warrior, and avenger—is the consummate test for each generation’s leading actors, and to be an era’s defining Hamlet is perhaps the greatest accolade one can earn in the theater. The play is no less a proving ground for the critic and scholar, as successive generations have refashioned Hamlet in their own image, while finding in it new resonances and entry points to plumb its depths, perplexities, and possibilities. No other play has been analyzed so extensively, nor has any play had a comparable impact on our culture. The brooding young man in black, skull in hand, has moved out of the theater and into our collective consciousness and cultural myths, joining only a handful of comparable literary archetypes—Oedipus, Faust, and Don Quixote—who embody core aspects of human nature and experience. “It is we ,” the romantic critic William Hazlitt observed, “who are Hamlet.”

Hamlet also commands a crucial, central place in William Shakespeare’s dramatic career. First performed around 1600, the play stands near the midpoint of the playwright’s two-decade career as a culmination and new departure. As the first of his great tragedies, Hamlet signals a decisive shift from the comedies and history plays that launched Shakespeare’s career to the tragedies of his maturity. Although unquestionably linked both to the plays that came before and followed, Hamlet is also markedly exceptional. At nearly 4,000 lines, almost twice the length of Macbeth , Hamlet is Shakespeare’s longest and, arguably, his most ambitious play with an enormous range of characters—from royals to gravediggers—and incidents, including court, bedroom, and graveyard scenes and a play within a play. Hamlet also bristles with a seemingly inexhaustible array of ideas and themes, as well as a radically new strategy for presenting them, most notably, in transforming soliloquies from expositional and motivational asides to the audience into the verbalization of consciousness itself. As Shakespearean scholar Stephen Greenblatt has asserted, “In its moral complexity, psychological depth, and philosophical power, Hamlet seems to mark an epochal shift not only in Shakespeare’s own career but in Western drama; it is as if the play were giving birth to a whole new kind of literary subjectivity.” Hamlet, more than any other play that preceded it, turns its action inward to dramatize an isolated, conflicted psyche struggling to cope with a world that has lost all certainty and consolation. Struggling to reconcile two contradictory identities—the heroic man of action and duty and the Christian man of conscience—Prince Hamlet becomes the modern archetype of the self-divided, alienated individual, desperately searching for self-understanding and meaning. Hamlet must contend with crushing doubt without the support of traditional beliefs that dictate and justify his actions. In describing the arrival of the fragmentation and chaos of the modern world, Victorian poet and critic Matthew Arnold declared that “the calm, cheerfulness, the disinterested objectivity have disappeared, the dialogue of the mind with itself has commenced.” Hamlet anticipates that dialogue by more than two centuries.

Like all of Shakespeare’s plays, Hamlet makes strikingly original uses of borrowed material. The Scandinavian folk tale of Amleth, a prince called upon to avenge his father’s murder by his uncle, was first given literary form by the Danish writer Saxo the Grammarian in his late 12th century Danish History and later adapted in French in François de Belleforest’s Histoires tragiques (1570). This early version of the Hamlet story provided Shakespeare with the basic characters and relationships but without the ghost or the revenger’s uncertainty. In the story of Amleth there is neither doubt about the usurper’s guilt nor any moral qualms in the fulfillment of the avenger’s mission. In preChristian Denmark blood vengeance was a sanctioned filial obligation, not a potentially damnable moral or religious violation, and Amleth successfully accomplishes his duty by setting fire to the royal hall, killing his uncle, and proclaiming himself king of Denmark. Shakespeare’s more immediate source may have been a nowlost English play (c. 1589) that scholars call the Ur – Hamlet. All that has survived concerning this play are a printed reference to a ghost who cried “Hamlet, revenge!” and criticism of the play’s stale bombast. Scholars have attributed the Ur-Hamle t to playwright Thomas Kyd, whose greatest success was The Spanish Tragedy (1592), one of the earliest extant English tragedies. The Spanish Tragedy popularized the genre of the revenge tragedy, derived from Aeschylus’s Oresteia and the Latin plays of Seneca, to which Hamlet belongs. Kyd’s play also features elements that Shakespeare echoes in Hamlet, including a secret crime, an impatient ghost demanding revenge, a protagonist tormented by uncertainty who feigns madness, a woman who actually goes mad, a play within a play, and a final bloodbath that includes the death of the avenger himself. An even more immediate possible source for Hamlet is John Marston’s Antonio’s Revenge (1599), another story of vengeance on a usurper by a sensitive protagonist.

Whether comparing Hamlet to its earliest source or the handling of the revenge plot by Kyd, Marston, or other Elizabethan or Jacobean playwrights, what stands out is the originality and complexity of Shakespeare’s treatment, in his making radically new and profound uses of established stage conventions. Hamlet converts its sensational material—a vengeful ghost, a murder mystery, madness, a heartbroken maiden, a fistfight at her burial, and a climactic duel that results in four deaths—into a daring exploration of mortality, morality, perception, and core existential truths. Shakespeare put mystery, intrigue, and sensation to the service of a complex, profound epistemological drama. The critic Maynard Mack in an influential essay, “The World of Hamlet ,” has usefully identified the play’s “interrogative mode.” From the play’s opening words—“Who’s there?”—to “What is this quintessence of dust?” through drama’s most famous soliloquy—“To be, or not to be, that is the question.”— Hamlet “reverberates with questions, anguished, meditative, alarmed.” The problematic nature of reality and the gap between truth and appearance stand behind the play’s conflicts, complicating Hamlet’s search for answers and his fulfillment of his role as avenger.

Hamlet opens with startling evidence that “something is rotten in the state of Denmark.” The ghost of Hamlet’s father, King Hamlet, has been seen in Elsinore, now ruled by his brother, Claudius, who has quickly married his widowed queen, Gertrude. When first seen, Hamlet is aloof and skeptical of Claudius’s justifications for his actions on behalf of restoring order in the state. Hamlet is morbidly and suicidally disillusioned by the realization of mortality and the baseness of human nature prompted by the sudden death of his father and his mother’s hasty, and in Hamlet’s view, incestuous remarriage to her brother-in-law:

O that this too too solid flesh would melt, Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew! Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d His canon ’gainst self-slaughter! O God! God! How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable Seem to me all the uses of this world! Fie on’t! ah, fie! ’Tis an unweeded garden That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature Possess it merely. That it should come to this!

A recent student at the University of Wittenberg, whose alumni included Martin Luther and the fictional Doctor Faustus, Hamlet is an intellectual of the Protestant Reformation, who, like Luther and Faustus, tests orthodoxy while struggling to formulate a core philosophy. Brought to encounter the apparent ghost of his father, Hamlet alone hears the ghost’s words that he was murdered by Claudius and is compelled out of his suicidal despair by his pledge of revenge. However, despite the riveting presence of the ghost, Hamlet is tormented by doubts. Is the ghost truly his father’s spirit or a devilish apparition tempting Hamlet to his damnation? Is Claudius truly his father’s murderer? By taking revenge does Hamlet do right or wrong? Despite swearing vengeance, Hamlet delays for two months before taking any action, feigning madness better to learn for himself the truth about Claudius’s guilt. Hamlet’s strange behavior causes Claudius’s counter-investigation to assess Hamlet’s mental state. School friends—Rosencrantz and Guildenstern—are summoned to learn what they can; Polonius, convinced that Hamlet’s is a madness of love for his daughter Ophelia, stages an encounter between the lovers that can be observed by Claudius. The court world at Elsinore, is, therefore, ruled by trickery, deception, role playing, and disguise, and the so-called problem of Hamlet, of his delay in acting, is directly related to his uncertainty in knowing the truth. Moreover, the suspicion of his father’s murder and his mother’s sexual betrayal shatter Hamlet’s conception of the world and his responsibility in it. Pushed back to the suicidal despair of the play’s opening, Hamlet is paralyzed by indecision and ambiguity in which even death is problematic, as he explains in the famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy in the third act:

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would these fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death— The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn No traveller returns—puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action.

The arrival of a traveling theatrical group provides Hamlet with the empirical means to resolve his doubts about the authenticity of the ghost and Claudius’s guilt. By having the troupe perform the Mousetrap play that duplicates Claudius’s crime, Hamlet hopes “to catch the conscience of the King” by observing Claudius’s reaction. The king’s breakdown during the performance seems to confirm the ghost’s accusation, but again Hamlet delays taking action when he accidentally comes upon the guilt-ridden Claudius alone at his prayers. Rationalizing that killing the apparently penitent Claudius will send him to heaven and not to hell, Hamlet decides to await an opportunity “That has no relish of salvation in’t.” He goes instead to his mother’s room where Polonius is hidden in another attempt to learn Hamlet’s mind and intentions. This scene between mother and son, one of the most powerful and intense in all of Shakespeare, has supported the Freudian interpretation of Hamlet’s dilemma in which he is stricken not by moral qualms but by Oedipal guilt. Gertrude’s cries of protest over her son’s accusations cause Polonius to stir, and Hamlet finally, instinctively strikes the figure he assumes is Claudius. In killing the wrong man Hamlet sets in motion the play’s catastrophes, including the madness and suicide of Ophelia, overwhelmed by the realization that her lover has killed her father, and the fatal encounter with Laertes who is now similarly driven to avenge a murdered father. Convinced of her son’s madness, Gertrude informs Claudius of Polonius’s murder, prompting Claudius to alter his order for Hamlet’s exile to England to his execution there.

Hamlet’s mental shift from reluctant to willing avenger takes place offstage during his voyage to England in which he accidentally discovers the execution order and then after a pirate attack on his ship makes his way back to Denmark. He returns to confront the inescapable human condition of mortality in the graveyard scene of act 5 in which he realizes that even Alexander the Great must return to earth that might be used to “stop a beer-barrel” and Julius Caesar’s clay to “stop a hole to keep the wind away.” This sobering realization that levels all earthly distinctions of nobility and acclaim is compounded by the shock of Ophelia’s funeral procession. Hamlet sustains his balance and purpose by confessing to Horatio his acceptance of a providential will revealed to him in the series of accidents on his voyage to England: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, / Roughhew them how we will.” Finally accepting his inability to control his life, Hamlet resigns himself to accept whatever comes. Agreeing to a duel with Laertes that Claudius has devised to eliminate his nephew, Hamlet asserts that “There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all.”

In the carnage of the play’s final scene, Hamlet ironically manages to achieve his revenge while still preserving his nobility and moral stature. It is the murderer Claudius who is directly or indirectly responsible for all the deaths. Armed with a poisonedtip sword, Laertes strikes Hamlet who in turn manages to slay Laertes with the lethal weapon. Meanwhile, Gertrude drinks from the poisoned cup Claudius intended to insure Hamlet’s death, and, after the remorseful Laertes blames Claudius for the plot, Hamlet, hesitating no longer, fatally stabs the king. Dying in the arms of Horatio, Hamlet orders his friend to “report me and my cause aright / To the unsatisfied” and transfers the reign of Denmark to the last royal left standing, the Norwegian prince Fortinbras. King Hamlet’s death has been avenged but at a cost of eight lives: Polonius, Ophelia, Rosencranz, Guildenstern, Laertes, Gertrude, Claudius, and Prince Hamlet. Order is reestablished but only by Denmark’s sworn enemy. Shakespeare’s point seems unmistakable: Honor and duty that command revenge consume the guilty and the innocent alike. Heroism must face the reality of the graveyard.

Fortinbras closes the play by ordering that Hamlet be carried off “like a soldier” to be given a military funeral underscoring the point that Hamlet has fallen as a warrior on a battlefield of both the duplicitous court at Elsinore and his own mind. The greatness of Hamlet rests in the extraordinary perplexities Shakespeare has discovered both in his title character and in the events of the play. Few other dramas have posed so many or such knotty problems of human existence. Is there a special providence in the fall of a sparrow? What is this quintessence of dust? To be or not to be?

Hamlet Oxford Lecture by Emma Smith

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Plays

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Bibliography Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Character Study Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Criticism Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , ELIZABEHAN POETRY AND PROSE , Essays Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Hamlet , Hamlet Analysis , Hamlet Criticism , Hamlet Guide , Hamlet Notes , Hamlet Summary , Literary Criticism , Notes Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Plot Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Shakespeare's Hamlet , Shakespeare's Hamlet Guide , Shakespeare's Hamlet Lecture , Simple Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Study Guides Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Summary Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Synopsis Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Themes Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , William Shakespeare

Related Articles

- Analysis of William Shakespeare's The Tempest | Literary Theory and Criticism

- Analysis of William Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra | Literary Theory and Criticism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Introduction

Hamlet by william shakespeare summary.

The play opens with Prince Hamlet being summoned to Denmark from Germany for his father’s funeral. When he reaches there, he finds that his mother Queen Gertrude has already remarried to his fraternal uncle, Claudius. For Hamlet, this marriage was a big shock and considered it “foul incest”. Even worse than this, Claudius has crowned himself disregard of the fact that being King’s son, this crown belongs to Hamlet. Hamlet doubts the whole scenario as foul play.

Hamlet, by his unwillingness to avenge Claudius, causes six subsidiary deaths. The first victim is Polonius, an old man, who is stabbed by Hamlet through a wall hanging as Polonius spies on hamlet and his mother. Claudius banishes Hamlet to England to punish him for Polonius’ death and instructs Hamlet’s school chums, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to handover him to English king for execution. Hamlet, during the journey, discovers what is going on and arranges a plot for the execution of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Ophelia, highly upset on her father’s death and Hamlet’s behavior, drown herself while singing a song and lamenting over the fate of a despised lover. Laertes, her brother, follows next.

Themes in Hamlet

The question of life and death is introduced just as the play opens. Hamlet, throughout the play, ponders the complexity of life and considers the meaning of life. Throughout the play, many questions emerge as what happens when one dies? Will someone directly goes to heaven, if he/she is murdered? etc. Furthermore, Hamlet is very uncertain about the afterlife and causes him to quit suicide. The death of almost all the major characters of the play, towards the end of the play, doesn’t fully answer the question of mortality. The character of Hamlet represents exploration and discussion disregard of a true perseverance.

Hamlet, after hearing confessions from the ghost acts like a mad person to fool people in order to know the reality of the people around him. He acts so to prove himself harmless. However, this madness was recognized by Polonius. The irony arises when he falsely believes that Hamlet’s method stems from his love for Ophelia. It was impressive of Polonius that he recognizes the method behind Hamlet’s madness.

Both of the ladies let Hamlet down. However, Ophelia is viewed as a victim of Hamlet brutality while Gertrude is represented as the more flexible character.

Political Livelihood

Hamlet characters analysis.

She is the Queen of Denmark and also the wife of deceased King Hamlet. She immediately remarries to Claudius, brother of King Hamlet.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern

Voltimand and cornelius, marcellus and barnardo, hamlet literary analysis.

The play has a turning point where Hamlet realizes at the graveyard and encounters the skull of a man whom he is fond of. In his contemplation, Hamlet realizes that death vanishes the class difference among society. Everything is created by man himself. All these differences are illusions that diminish with death.

More From William Shakespeare

the starving artist

I'm determined. are you, book review: hamlet.

The story of Hamlet was based on the Dane Amleth, recorded in history by Saxo Grammaticus. Shakespeare might have written an earlier telling of the story, known today as Ur-Hamlet, and three distinct versions survive today, each with particular omissions and inclusions. “Hamlet” is Shakespeare’s longest play, one of his most complex (leading to wide and various interpretation) and respected, and his most popular during his lifetime. It is known as the most filmed story in history, after Cinderella, and leads many theaters in number of performances over time.

There are different ways to approach plays as literature. Even a simple reading of play reviews on Amazon will show that some believe a reading of a play can add to it, while others see the performance of the play as the true actualization. I tend to believe more in the performance as the thing, so I am not sure that reading is really the fairest way to judge a play. However, what performance would you judge a play on, anyhow? Perhaps a conglomeration of the performances? Or a perfect performance idealized by a professional read of the play? That’s a bit too abstract for us, so I’ll just stick to judging the play by my read and then chatting about any video performance I could get my hands on.

Now, due to passage of time between Shakespeare’s writing and the modern man, most people can not just pick up Shakespeare and read it without help. To us, the language is archaic and difficult, and there are plenty of allusions and assumptions that need notes to fill us in. On the other hand, since Shakespeare is taught widely in English-speaking schools and still culled for movies and other entertainment, many of us can eke our way through. I happen to love Shakespeare, so my returning to his works over time has left me with an ability to read it straight, for the most part. However, it is helpful to many to read a synopsis of the play before reading the play, keeping a resource handy to interpret certain passages or confusing words. Unfortunately, full appreciation of Shakespeare is lost on all but the experts, since we are so far removed from his times and his culture. However, even a vague understanding can lead to vague awe.

I find myself impressed by how many thoughts and phrases emerge from “Hamlet.” Within four lines appear “Neither a borrower nor lender be,” and “To thine own self be true.” The text is rife with common quotations and high points of theatrical history. However, it is not one of my favorite Shakespearean plays. When I started to read it (again; I’ve read it before), I was confused by Hamlet’s character, not sure whether he is mad or not and so forth. By the time I was done with my reading and all my viewings, I found Hamlet to be a spoiled prince baby, repugnant in the way he deals with others around him, as if they are cheap or mere playthings. It’s also not my favorite Shakespearean storyline, because, although it is pregnant with great twists and turns, it sort of lacks a flow which makes some of his other plays sleeker.

But of course, “Hamlet” is one of the standards of world literature, and I would not skip it or ignore it just because the Prince of Denmark is confusing or juvenile. Better critics than I put it right at the top of their lists. And anyway, part of the experience is in the interpretation, in seeing it performed, which leads us to the movies I could find.

“‘…my cousin Hamlet, and my son–‘ / ‘A little more than kin, and less than kind'” (p1074).

“Thou know’st ’tis common–all that live must die…. Why seems it so particular with thee?” (p1074).

“I know not seems” (p1074).

“You must know, your father lost a father; That father lost, lost his” (p1074).

“Frailty, they name is woman!” (p1074).

“…best safety lies in fear: Youth to itself rebels” (p1076).

“Give thy thoughts no tongue…. Give every man thine ear, but few thy voice: Take each man’s censure, but reserve they judgement” (p1076).

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be: For loan oft loses both itself and friend” (p1076).

“…to thine ownself be true” (p1076).

“…these blazes, daughter, give more light than heat (p1077).

“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” (p1078).

“And thy commandment all alone shall live Within the book and volume of my brain, Unmix’d with baser matter” (p1079).

“There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy” (p1080).

“The time is out of joint” (pp1080).

“…brevity is the soul of wit” (p1082).

“How pregnant sometimes his replies are! a happiness that often madness hits on, which reason and sanity could not…” (p1084).

“‘Denmark’s a prison.’ / ‘Then the world is one'” (p1084).

“…they say an old man is twice a child” (p1085).

“…use every man after his desert, and who should scape whipping? Use them after your own honour and dignity: the less they deserve the more merit is in your bounty. Take them in” (p1087).

“…the devil hath power To assume a pleasing shape” (p1087).

“…the play’s the thing Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king” (p1087).

“To be, or not to be,–that is the question” (p1088).

“…ay, there’s the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause…” (p1088).

“The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn No traveller returns…” (p1088).

“Thus conscience does make cowards of us all” (p1088).

“Rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind” (p1089).

“…the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature…” (p1090).

“A second time I kill my husband dead When second husband kisses me in bed” (p1091).

“Our wills and fates do so contrary run” (p1092).

“Never alone did the king sigh, but with a general groan” (p1094).

“And how his audit stands who knows save heaven? (p1094).

“Assume a virtue, if you have it not …. For use almost can change the stamp of nature…” (p1096).